25 September 2024. Economics | Migration

Tackling Britain’s low-productivity problem // How migration can regenerate declining towns [#603]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Tackling Britain’s low productivity problem

My feeds are suddenly busy with news of the Foundations report, from Works in Progress, which believes it has identified the reasons for Britain’s low productivity and investment performance. It’s getting a lot of attention.1

The first thing to say is that I agree with their problem statement. British productivity per worker is too low, and this has real political consequences for our ability to provide good public services. (I wrote about this issue here just before the UK election.)

The second thing to say is that the story they tell is a bit scattershot. It’s all about finding ways to build things, and some of this makes sense, and some doesn’t. Here’s their summary of problem and their view of the reasons it exists:

Real wage growth has been flat for 16 years. Average weekly wages are only 0.8 percent higher today than their previous peak in 2008. Annual real wages are 6.9 percent lower for the median full-time worker today than they were in 2008. This essay argues that Britain’s economy has stagnated for a fundamentally simple reason: because it has banned the investment in housing, transport and energy that it most vitally needs.

'Banned’ is a strong word of course, but the analysis comes with some figures about how expensive, and in some cases how difficult, it is to build things in Britain, and indeed how much harder it is than in France, which they take as a comparator. ‘Things’ isn’t quite the right word; they are specifically interested in roads and related transport, power stations (especially nuclear power stations), and housing:

Housing supply is vastly freer in France. Overall, it now has about seven million more homes than Britain (37 million versus 30 million), with the same number of people. Those homes are newer, and are more concentrated in the places people want to live...

Transport infrastructure is now better there: there are seven British tram networks, versus 29 in France. Six French cities have underground metro systems, against three in Britain. Since 1980, France has opened 1,740 miles of high speed rail, compared to just 67 miles in Britain...

Energy is more abundant and, thanks to the country’s nuclear roll-out from the 1970s, the country has already done a lot of decarbonisation.

(‘Foundations’ is a big fan of French motorways. Copyright free image via Wikipedia)

The reason all of this mostly matters to them is because they believe that greater productivity is down to ‘agglomeration’—more people with common interests in the same place. To be fair, this is the current dominant view of why cities prosper, even though it may be an idea that is running out of road.

I’m going to pause here, because you get the idea. My go-to model for thinking about strategy is Richard Rumelt, and he summarises good strategy as coming in three parts:

A diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge. A good diagnosis simplifies the complexity by identifying the critical aspects of the situations.

A guiding policy for dealing with the challenge.

A set of coherent actions that are designed to carry out the guiding policy.

Specifically, he says that a good diagnosis

should replace the overwhelming complexity of reality with a simpler story, a story that calls attention to its crucial aspects.

So when faced with a report such as Foundations, the place we need to start is the diagnosis. There are other explanations of Britain’s low-productivity economy available. The Resolution Foundation for example, which published its version of this report last December, largely put it down to being a low wage economy with long-term low levels of private and public investment (these two factors are related.)

Abby Innes, whose book Late Soviet Britain I’m reading at the moment, identifies the aggressive application of neoliberal and neo-classical economic models to policy. Nicholas Shaxson blames the large size of the British financial sector. There are plenty for whom Osborne’s austerity is to blame. Brexit has been an additional kicker.

The authors of Foundations—Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman—nod towards alternative explanations, but not in a way that suggests they take any of them seriously. Because they have a single view of the problem and they are keen to prove it.

Let’s take the housing problem. This, apparently, is down to the post-war Labour Party Prime Minister Clement Attlee and the 1948 Town and Country Planning Act [TCPA]. To be clear, I agree that Britain needs more housing, but their explanation of the problem is partial, to say the least.

It also says something about their approach to making their case. Here’s their chart on this:

(Source: Foundations)

Apparently the TCPA had stymied housebuilding:

The TCPA completely removed most of the incentive for councils to give planning permissions by removing their obligation to compensate those whose development rights they restricted... Since the TCPA was introduced in 1947, private housebuilding has never reached Victorian levels, let alone the record progress achieved just before the Second World War.

I had remembered housing completions as staying high—and steady—in the thirty years from the late 1940s. This chart doesn’t seem to show that, so I thought I’d better check the data. Housing completions were 230,000 in 1948, and ran at more than 300,000 a year, sometimes more than 400, for most years until the 1970s. During the 1980s, housing completions were still more than 200,000 a year. Since 1990, there have been only five years where completions have been greater than 200,000.

What made the difference? Until the late 1970s, councils and other social builders put up a lot of houses. That number fell sharply after the Thatcher government created the ‘right to buy’ and made it impossible for councils to finance housing. So it turns out that the TCPA, which is an important part of their argument, wasn’t really the reason for any of this.

The other thing about infrastructure is that it is not, of itself, a good thing, and this point keeps getting elided in the story being told about how difficult it is to build infrastructure in Britain. China’s ghost cities, connected by unused roads, are testament to that. Infrastructure is only useful if it makes productive things happen.

If we are looking at productivity through an infrastructure lens, it’s hard to make the case that more motorways in the UK will drive more productivity (the costs of congestion are fractions of a percentage point of total costs; the costs of climate change are not.) It’s hard to make the case for the Lower Thames Tunnel. Unless you own Heathrow, it’s hard to argue, as the authors do, that it matters that “Heathrow annual flight numbers have been almost completely flat since 2000.”2

Equally, while building cost-effective nuclear power stations mighthave been a good idea in the 1980s (there were also arguments against) it makes no sense now when the lifetime price of nuclear electricity is going to be higher than wind, solar, and storage, and electrification (for example of the transport system) will reduce overall demand. Again, there are credible arguments that it was the failure to invest in renewables during the 2010s (David Cameron cutting the “green crap”) that is the reason that British energy is more expensive.

And talking—as they do—about how fast Paris has grown compared to London may be good for a rhetorical point, but ignores the fact that Paris is still smaller than London, and that in terms of size London is at about the limits of an effective city (because travel time ends up being a significant constraint.)

Reading their excitement about infrastructure, in fact, I had a flash of Marinetti’s futurist manifesto or Stephen Spender’s poem about electricity pylons. And certainly, Ben Southwood loves his motorways.

Oddly, one of the points about the difference between Britain and France, which is used here as a negative, may be some of the reason why French levels of investment are higher. In his summary of the report, Ed West notes,

France is the most natural comparison point to Britain, a country ‘notoriously heavily regulated and dominated by labour unions.’... It is also heavily taxed, especially in the realm of employment.

If labour is more expensive, employers are encouraged to invest in technology to get more out of their workers. I’m reminded of a piece by Mike Haynes in The Conversation about the hand car wash, in contrast, as the exemplar of Britain’s productivity problem.

The element of infrastructure that does matter here is infrastructure that makes local and regional labour markets work better. Across the Midlands and large chunks of the North of England the dreadful regional transport infrastructure gets in the way of effective local labour markets. There’s well established research that suggests this would have a meaningful effect on productivity.

So I have some sympathy here for the observation in the Foundationsreport that

There are now French cities of 150,000 people with fast modern tram systems - towns comparable in size to Carlisle or Lincoln.

And yes, it costs more to build tram systems in the UK than France.

Some of this is changing now: Birmingham, for example, is reopening train lines. But the reasons for this historic regional transport issue aren’t that much to do with building. The first is that the Treasury has operated a “success to the successful” investment model that broadly ensures that areas with existing high productivity will get more investment. And the deregulation of local bus services meant that councils had no control over their local and regional transport systems.

Complex socio-economic issues rarely have monocausal origins or monocausal solutions. Diagnosis matters.

2: How migration can regenerate declining towns

I have written about migration here a few times recently (links at the end of this post) partly as a result of a project I did last year and this on Reimagining Mobility and Migration for the International Organization of Migration [IOM]. So I was immediately intrigued when the American economics blogger Noah Smith wrote a piece at his Noahpinion blog on how migration could regenerate—and in some cases has regenerated—declining towns in those parts of the United States that are losing population.

As it happens, when I ran the futures workshop that informed the IOM report, one of the groups explored exactly this scenario, so it is interesting to see Smith work through what happens in practice.

Before I get into the detail of this, I should note some slackness in language. The post is headlined ‘How will you save small midwestern towns without mass immigration?’, and he refers to ‘mass immigration’ throughout. Two obviously points here—the notion of ‘mass immigration’ is routinely deployed as rhetoric by right wing groups; and the numbers he’s talking about are not large. So it’s a puzzle as to how he’s fallen into this language. At least without putting it into quotation marks.

The American data—which may well be similar in other countries—suggests that Americans are in favour of high-skilled migrants. There’s not much data on what they think about “low skilled migrants”. But that’s partly because it is a bit of a vague category that covers quite a wide range of people.

All the same, Smith argues, even in the absence of data, it’s important:

It’s the type of immigration that the Trump campaign raged against in the recent fracas over Haitians in the small city of Springfield, Ohio. And it’s type of immigration that Trump raged against back in 2016 when he targeted Somalis in Maine. In fact, mass low-skilled immigration has become pretty common in small cities and rural areas across America.

Just a moment’s pause here, because this isn’t quite right politically. What Trump and Vance are doing is blurring low-skilled migrants with undocumented migrants and others, which is a classic right-wing trope. (And that word ‘mass’ again!)

But Smith is better on economics than politics, fortunately.

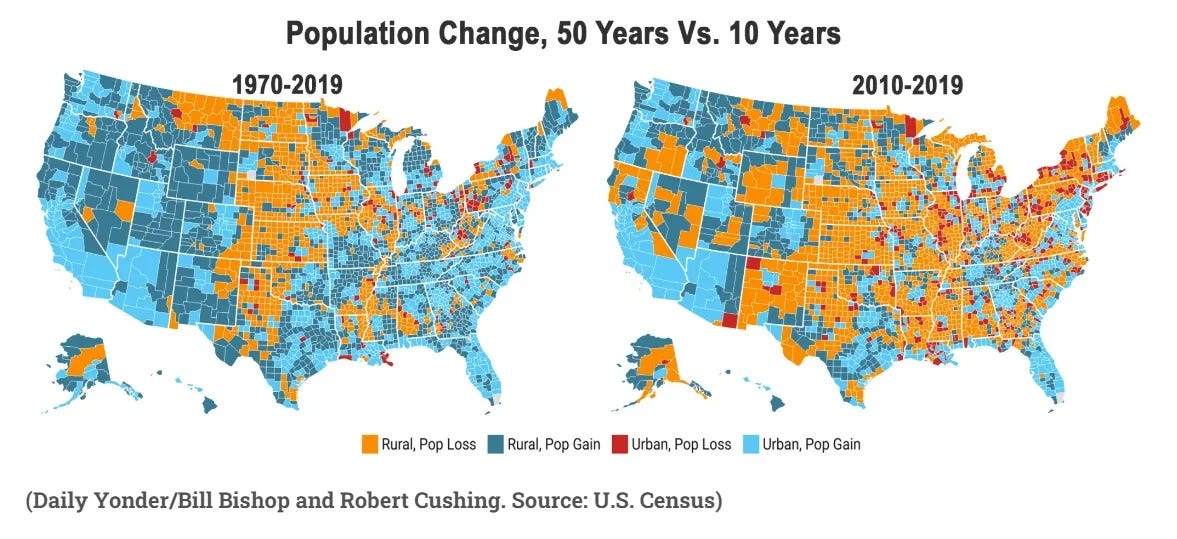

And he starts with the decline problem, as seen in this pair of maps.

(Source: Robert Cushing)

In short, there’s a lot of places that are in decline and they seem to be getting worse:

You can see that the number of declining places has accelerated in recent years. It now includes big swathes of the Great Plains, the Midwest, the Deep South, and the interior of the Northeast. This is due to a combination of factors, but fertility decline and a greater desire for city living are the main ones.

Once decline sets in, it is hard for a town to reverse this. Its built infrastructure becomes harder to maintain, because it is being paid for by a smaller tax base; shops close because they aren’t viable on a smaller customer base,

so lots of commercial spaces get boarded up and vacated. Drug people move into those spaces, and they become urban ruins. A pall of despair settles over the whole town.

But it turns out that low-skilled immigration can reverse this, and this has happened in a number of places. What Smith means by ‘mass’ is that several thousand migrants—typically from the same culture or country of origin—end up in one of these towns.

This happens because migrants tend to move to places where there are people they already know, or where they know they won’t be out of place. In fact a lot of the history of America was a bit like that.

A report from Fwd.US (a thinktank founded by Mark Zuckerberg) tells the story of how this happened in practice in Franklin County, Alabama, and its county seat, Russellville:

Russellville’s longtime public librarian describes the downtown’s transformation: “We saw an influx of immigrants moving to the area looking for work, and they started opening little shops, grocery stores, furniture stores, restaurants, bakeries, places like that. We’ve now seen the entire downtown area be brought back to life, and the majority of that revitalization can be attributed to the immigrants who moved here.”…

Immigrants have been drawn to jobs at meat processing plants in the area. But, they have also started new businesses, like La Niña, and have established new churches for their growing number of Spanish-speaking congregants.

(Jackson Avenue, Russellville. Photo: Brian Stansberry/Wikimedia, CC BY 4.0)

It’s just worth noting the numbers here, from the Franklin County census data. In 2000, the population of the county was 31,223; it dipped a little in 2010; in 2020 it was 32,113. In terms of racial mix, over that twenty years the proportion of the population that is white has fallen (from 87% to 73%) , and the proportion that is Hispanic has grown steadily (from 7% to 19%, or around 2,300 to 6,300), with little change in other ethnic categories.3

There’s a pattern here, and other small towns that have seen more migrants arrive tell a similar story: newcomers are initially met with suspicion, and schools struggle with teaching kids for whom English is a second language. But as the new arrivals start opening shops and small businesses, the town life becomes more optimistic, and sometimes benefits from an ethnic flavour.

Smith quotes academic work by Celeste Lay, a political scientist who studied differences between mid-Western towns that experienced an inflow of migrants, and those that didn’t:

Lay collects both quantitative evidence (surveys, which she compares to surveys from the surrounding towns that didn’t get many immigrants), and qualitative evidence (interviews with local residents). She finds the same old American story: initial wariness and even some hostility to the newcomers, followed by broad acceptance and tolerance as locals get to know the newcomers. The Contact Hypothesis wins again, and the American mosaic becomes more colorful, etc. etc.

Smith wonders why this experience isn’t reflected in the discourse about migration, and of course there are several reasons for this, one of which is that (not just in the US) people with the least experience of migrants are generally most hostile towards them, and political parties are able to make political capital by exploiting this.

But as he suggests: if we want to revive declining towns, is there another alternative out there which might do it better? He thinks not:

How else do you propose to revive those declining regions? Would you starve them of the only resource that they could possibly use to revitalize themselves? Would you just tell all the people in those towns to pack up and move to New York and Chicago? What’s your alternative plan? Because I honestly don’t see any other way those places are going to get saved.

Read more:

Update: Work

Jon Cherry, who writes the Cherryflava.com blog, picked up on my recent piece on work, pulling out this observation:

Last week Andrew posted a piece about the ongoing Return To Office mandates (RTO) that are sparking some debate in some circles, which is well worth the time to read (especially if you are currently intellectually toying with potentially ordering staff back to their desks). As we have repeatedly lamented on this site - simply ordering staff back to the office doesn't necessarily solve the productivity challenge that it is supposedly meant to be addressing.

And then a couple of days later, the Amazon CEO Andrew Jassy demonstrated my point that the companies that were obsessed with RTO mandates were in a subset of sectors that were dominated by ideas about management control, by announcing that Amazon staff would be required in the office five days a week. We’ll be able to see from their staff turnover figures how that goes.

A subsequent piece by Jonathan paired that Amazon announcement with the publication of a short article in Nature that said that hybrid work improved workplace satisfaction and reduced employee turnover. Here’s the money quote:

...hybrid working improved job satisfaction and reduced quit rates by one-third. The reduction in quit rates was significant for non-managers, female employees and those with long commutes. Null equivalence tests showed that hybrid working did not affect performance grades over the next two years of reviews.

But RTO mandates aren’t about evidence.

—

j2t#603

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Works in Progress, by the way, is a project funded by Stripe—the payments company run by the Irish Collinson brothers who are at the more likeable, and interesting, end of Silicon Valley’s billionaire spectrum. It’s quirky, but it does have a discernable worldview.

The majority of the passengers in and out of Heathrow are leisure passengers; many do not come into the UK at all but pass through. The Davies Commission just about constructed a business case to support Cameron’s turn-around on the Third Runway but the numbers and assumptions do not withstand any critical reading.

Again I’m labouring the point, but this is not a rate of change that speaks of ‘mass’ immigration or an ‘influx’.