29 June 2024. Economics | Nature

Wrestling with Britain’s ‘stagnation’ crisis // Facing up to the crisis of the natural world

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Apologies for the short break. I have been away, and also writing something, and have had less time than I expected.

1: Wrestling with Britain’s ‘stagnation’ crisis

We’re less than a week away from the date of the UK General Election, and one of the rules of Just Two Things is that I try only to write about UK specific issues if there are wider lessons to be learned. But one of the lessons of the election campaign so far is the inability of politicians to talk about difficult issues.

Because this chart (taken in this version from the Financial Times) is really the only thing you need to know about British politics at the moment.

(Source: FT analysis of UK data)

What it shows is that after 2008, or so, the British economy fell off the track of the rate of growth that it had been on for the previous 50 years, and jumped to another track.

That trend line from 1960-2010 had not been particularly compelling—it was still slower than other comparable economies—but it did trend upwards.

The best single explanation of this is the austerity policies that the Cameron-Osborne led Coalition government chose to follow, ostensibly to deal with the level of government debt incurred in dealing with the financial crisis.

There are different versions of why they opted for this. The plain vanilla version of this is that Osborne saw a presentation by Reinhart and Rogoff of their 2010 research paper that said that when debt climbed above 90% of annual GDP it choked off growth. This is, of course, the research paper that has the most famous spreadsheet error in economics history.

It’s worth spelling out the mistake:

[T]his 90% figure was employed repeatedly in political arguments over high-profile austerity measures... The most serious [of three errors identified] was that, in their Excel spreadsheet, Reinhart and Rogoff had not selected the entire row when averaging growth figures: they omitted data from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada and Denmark... When that error was corrected, the “0.1% decline” data became a 2.2% average increase in economic growth.

This error was exposed in 2013, and Osborne did not change his policy as a result, even though austerity had evidently not improved growth by then.

So a more credible explanation is that he believed in cutting back state spending for ideological reasons. He also finagled his cuts in such a way that local councils would be blamed from them rather than central government, which is why many British councils are currently at risk of bankruptcy.1

The most direct political consequence of these continuing cuts to the UK social fabric, and slower economic growth was the vote in favour of Brexit. There is research by Thiemo Fetzer at Warwick Universitythat suggests that austerity and its related welfare measures was enough to swing the vote from Remain to Leave.2

Either way, the effect of these two, in combination, was enough to create a cycle in which business confidence declined and therefore business investment declined, leading to lower growth—and stagnating wages. I could do a causal loop diagram of this, but in 2024, what this lost decade and a half means in practice—according to the economist Simon Wren-Lewis is that households have lost £35,000 in resources, measured in today’s prices, over the last 15 years. And the UK tax base is correspondingly smaller. (It’s possible to argue about whether growth is a sensible target, but higher productivity, which always requires investment in people and systems, is almost always worth having more of. Higher productivity creates social and economic opportunity, including opportunity for shorter working hours).

Here’s an IMF chart, also via the Financial Times, that tells the same story in a comparative way.

(Source: International Monetary Fund)

That’s Britain, down near the bottom.

So, in effect, the only way that British citizens can have nicer things, at least in terms of public services, is if the Government can find ways to end this 15-year stagnation.

The odd thing about this is that outside of the revanchists on the right of the Conservative Party, there’s not much disagreement about this. Rachel Reeves, who seems likely to be the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer this time next week, addressed it in a Mais Lecture early this year.

Her mantra then was about the “smart and strategic state”, whatever that means. Underlying this, though, she was clear that more stagnation could put democracy at risk, and that policy needed to reduce regional inequality. Her recipe for doing something about it then was, in Martin Wolf’s summary,

stability; “stimulating investment through partnership with business”; and reforms that will unlock productivity.

This sounds as if it is heading in the right direction, even if it probably isn’t enough to deal with the scale of the problem. In practice, when she gave that lecture in March, she talked about new public institutions to help enable investment, using pension fund investment more strategically, and dealing with the UK’s planning system.3

Since then, as we have got into an election, we have also seen proposals to deal with in work poverty and insecurity. These would probably increase productivity, even though they appear to have been misunderstood and then criticised by Britain’s keepers of economic orthodoxy, as Paul Mason pointed out in a thread on Twitter/X last week.

When I say that there’s not much disagreement on this, it’s because the Conservatives Nick Timothy and Gavin Rice have recently written a paper—endorsed by the Conservative front-bench politician Michael Gove—that says much the same thing, even if some of the policy emphasis varies.4 (My thanks to Ian Christie for sending it over to me.) The paper, published by the Onward group, argues that

[W]e face huge challenges from low household incomes and regional imbalances to poor productivity and a lack of investment... The paper makes the case for an active industrial strategy to rebuild Britain’s manufacturing base, boost exports and make it less reliant on overseas ownership of its core strategic assets. It calls for an economic policy to prioritise national productivity and security over international rent-seeking or libertarian ideology.

What’s striking about these analyses, though, is what they leave out. The ‘Overton Window’ on financing government expenditure has become miserably small. The tax story being told during the election has only the most trivial ideas—and only hinted at—on taxing wealth. This involves bringing Capital Gains Tax up to the same rate as income tax, which should have been done on tax equity grounds a long time ago. It is mute on the economic benefits of forms of public ownership. And discussion of the way public investment actually works in practice has been primitive.

So primitive, in fact, that bond market traders popped up in the Financial Times to tell Rachel Reeves that the bond markets would be completely happy if she raised bonds to invest in infrastructure. (The way she and Labour leader Keir Starmer walked back from their earlier proposals to invest £28 billion on transition/climate infrastructure was one of the most embarrassing acts of their leadership).

That’s behind a paywall, so here’s an extract:

“If Labour borrows to invest, markets will not worry about it,” said Tom Roderick, portfolio manager at hedge fund firm Trium Capital. “What markets are more worried about is borrowing to cut taxes, or increase social security payments, which doesn’t sound that likely.”

It’s quite an achievement for the Labour party to be to the right of the bond markets. But the important point here is that the only likely way to end stagnation is by government taking the lead on investment, as the Biden administration did. And not doing it in a way that could potentially be transformational because you have got confused about some basic economic principles would be unforgivable. People keep telling me that neoliberalism is dead, but its cold bony hand is still gripped tight around the imaginations of our political class.

2: Facing the crisis of the natural world

The John Muir Trust, which looks after a number of important open spaces in the UK, and promotes the value of nature in general, and trees in particular, celebrated its 40th anniversary last year. The art competition they organised to mark the anniversary, “Creative Freedom,” has been the subject of a small exhibition in their building in Pitlochry in Scotland, and I was able to sneak in on the last day the exhibition was open.

Muir was a Scots-born naturalist and ecologist whose family moved to America, when he was 11, in 1849, for religious reasons. He was fantastically influential, helping to establish Yosemite National Park and the Sierra Club, and exploring Alaska. The John Muir Trust in the UK was established in 1983, and among other things it looks after parts of Ben Nevis in Scotland and the remote Sandwood Bay.

The winners of the competition on display were all high quality, but I’ve picked out the more interesting ones here.

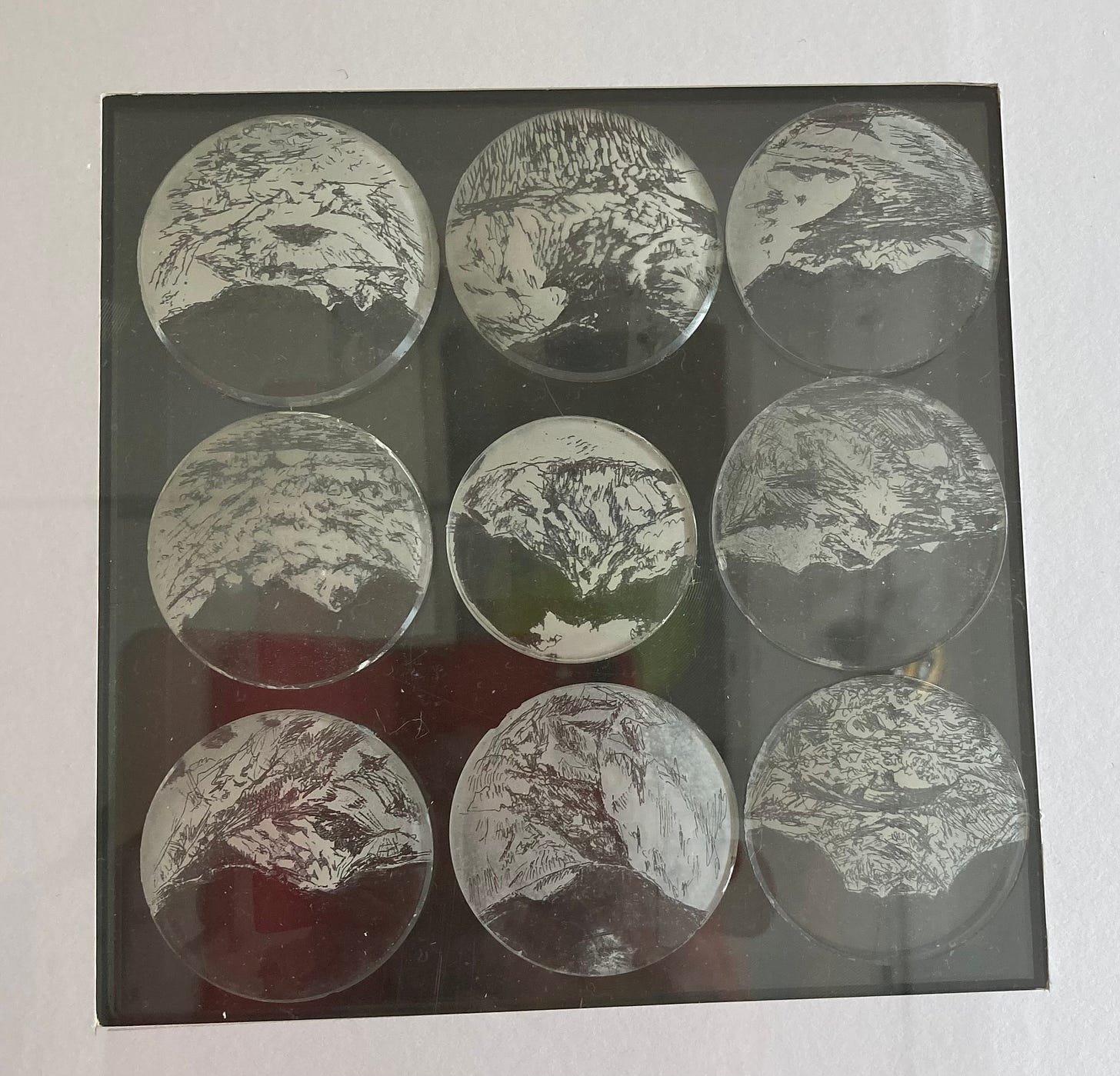

(‘Solastalgia’. Photo: Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Lizzie Wood had drawn a short graphic book about the idea of ‘solastalgia’, which is a notion first developed by Australian environmentalists to describe the experience of loss of a familiar environment through climate change.

Her cartoon strip was about Britain, and our experience of trees in the country, and you can read it online here. (The Trust also interviewed her about it.)

(Page from ‘Solastalgia’, by Lizzie Wood. (C) Lizzie Wood)

I was struck by this page in particular where she discusses solastalgia, because the text raises quite an interesting question.

Here’s her definition:

Solastalgia, in contrast to the dislocated spacial and temporal dimensions of nostalgia, relates to different circumstances. It is the pain experienced when the place where one resides and that one loves is under immediate assault. It is an intense desire for that place to be maintained in a state continues to give comfort or solace. Solastalgia is not about looking back to some golden past, nor is it about seeking another place as 'home'. In short, solastalgia is a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at ‘home’.(Emphasis in original).

The question she raises in the text is this:

I WONDER HOW MUCH CLAIM I HAVE TO THIS WORD - WHEN I AM A STRANGER TO THESE LANDSCAPES, THAT NEITHER RAISED ME, NOR GAVE ME MY NAME.

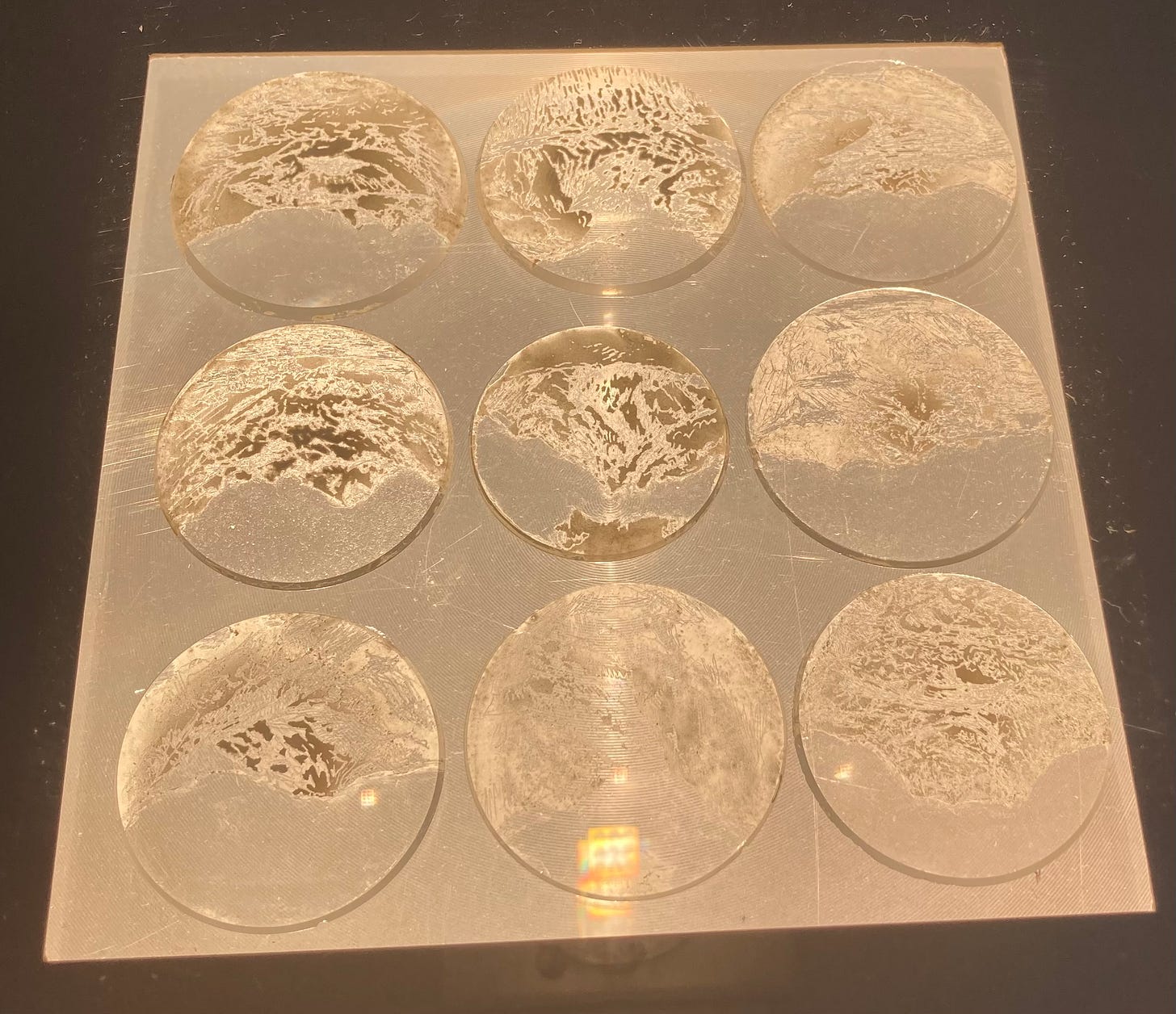

Mentioning a couple of the other exhibits quickly, Sarah Casey had installed nine watch faces painted with glacier flour—title: Long Shadows Cast—under a projector light. Leaving aside the thought processes here (time, glaciers, running out etc), the visual effect was interesting. With the light turned off, there were nondescript. With the light on, they conjured a sepia effect, as if turning the clock back to the nineteenth century and the sense of awe that glacier landscapes created for explorers of John Muir’s generation.

(Sarah Casey, ‘Long Shadows Cast’. Above: unlit. Below, lit).

Therese Lynch is an artist who was an artist in residence at Café Tissardmine in the Moroccan Sahara in March 2023, and she would collect rubbish from the desert as she walked in the area near the cafe:

Daily, I’d walk for a couple of hours, picking up rubbish along the way. Usually plastic bottles, discarded by tourists. Sometimes rope or bags.

(Therese Lynch, from Salvage. (C) Therese Lynch)

From this she constructed a field of plastic blooms that she installed near the cafe.

(Therese Lynch, from Salvage. (C) Therese Lynch)

Installed outside the cafe, it looks like a field of Spring blossoms, temporary, fragile. Belying the belligerent permanence of the materials.

The short video of the installation (less than a minute long) can be seen online here.

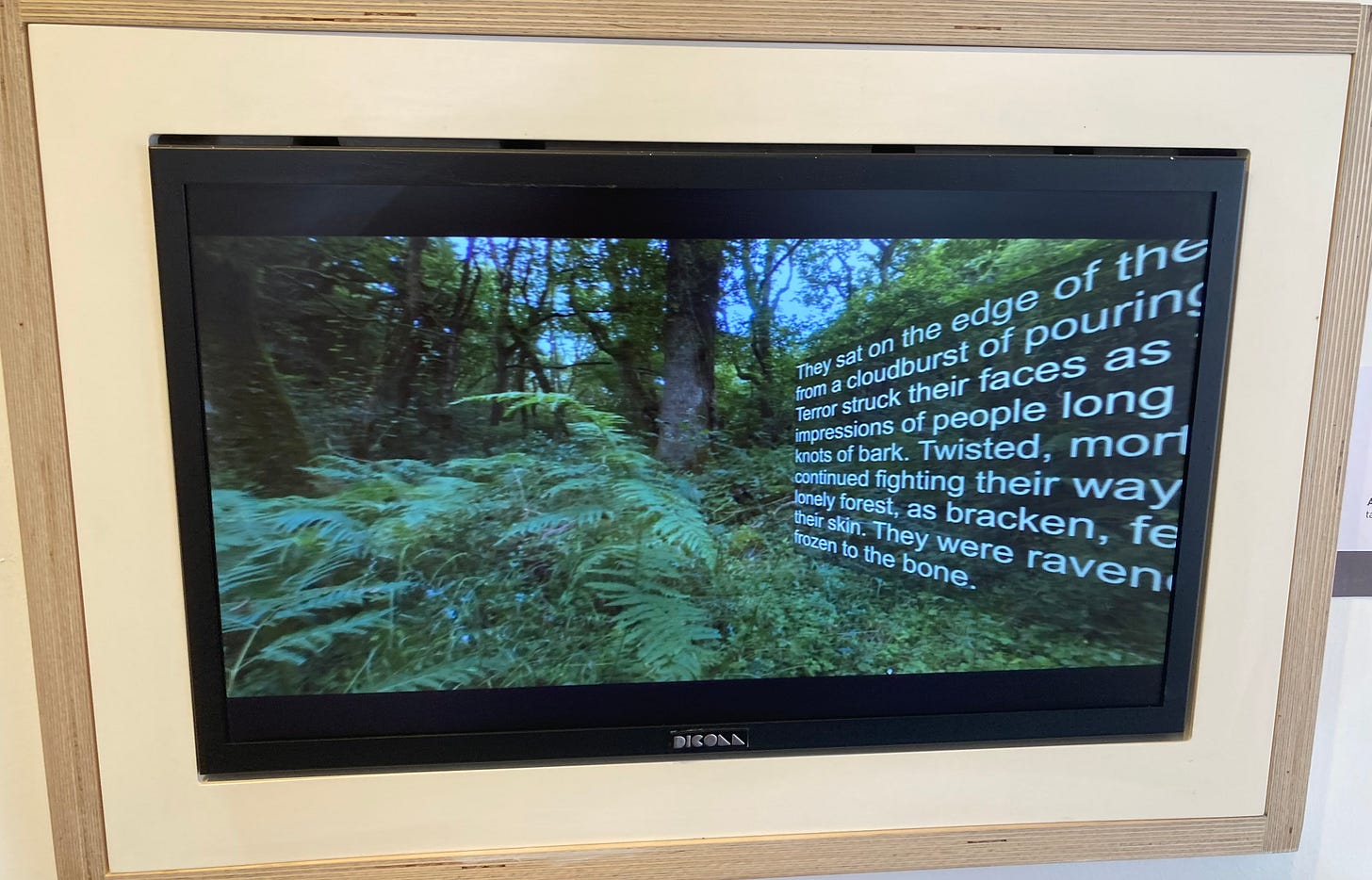

Finally, a group called Young Somerset—a group of 11-14 years olds—had worked with a writer, Craig Dent, to produce a 50 year story told in video and filmed with a 3D camera that started in 2043 and wrapped up in 2093. It starts as a dystopia and may not end that way.

(Photo: Andrew Curry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Here’s an image from that, but the online version is much more fun. It involves a multimedia headset and a bit of Virtual Reality emulation that allows you to enter into their world.

https://storage.net-fs.com/hosting/6657180/66/

j2t#584

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

‘Friends of George’ also spent much of the early Coalition years telling journalists that George was a political strategy genius because of this attempted misdirection, which claims journalists seemed happy to publish without thinking about them at all.

If you are interested in this it’s also worth reading the discussion rebutting critics of the paper.

Wolf assumed that the British Treasury (finance ministry)—which has been party to the wrecking of the British economy because of its narrow and rigid thinking—would do the best it could to kill off the proposals for new public institutions, whether or not they were a good idea.

Yes, that is the same Michael Gove who has been in the government for most of past 15 years; yes, that is the same Nick Timothy who worked closely with Theresa May when she was Britain’s Prime Minister.