14 June 2024. Populism | Grenfell

Emigration, not immigration, is a clue to populism. // Grenfell, Aberfan, and the ‘Core Group’

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Emigration, not immigration, is a clue to populism

The futurist and writer Paul Raven, who collaborated with me on our recent report on Rethinking Migration and Mobility, has sent me a link to some research published in The Conversation that connects migration and populism—but not in the way that you’d expect.

The research is by Rafaela Dancygier at Princeton at Stanford, and David Laitin at Stanford, and maybe it takes some distance to see a new data pattern underneath the toxic swirl that hangs around most discussion of populism and migration:

The idea of recapturing voters by appearing tough on immigration is attractive to established parties, but, as scholars of comparative politics and political behavior, we believe that this strategy won’t return many votes.

The reason for this, they say, is that the relentless focus on immigrationobscures the effect of emigration from a region or locality as a factor in shaping political attitudes:

In a recently published study, our research team found a relationship between out-migration from counties and an increase in votes for populist radical right parties in 28 European countries during the mid-2010s.

One of the features of advanced service-based economies is that younger people leave tons and villages in rural areas for cities in search of education and better work. Some of the effects of this are now stark. Spain has lost more than a quarter of its rural population in 50 years; the figures are similar in Italy. The United States has seen some rural counties suffer sharp population losses.

This is normally researched as an economic issue. Dancygier and Laitin have instead looked at it as a psephological issue.

Sweden provides some useful data. Between 2000 and 2020, the country’s immigration population increased from 11% to 20% (including Paul Raven, as it happens). At the same time, half of Sweden’s municipalities experienced population decline as people moved to Stockholm, Malmo and Gothenburg.

(A church in rural Sweden. Via Pixabay. Public Domain)

Over the same period, the once-dominant centre-left Social Democratic Party has declined in popularity, and the populist anti-immigrant Sweden Democrats now hold a fifth of the seats in the country’s Parliament. The country is governed by a centre-right coalition with support from Sweden Democrats.

Despite their anti-immigrant politics, their support has grown in areas that were unaffected by immigration:

looking at elections over two decades, we found that it was in municipalities that lost population that the radical right was able to score big gains. What’s more, local immigration was much less of a factor behind this success compared with local out-migration.

Looking at data over five elections, the researchers found a gain of half a percentage point in vote share for the Sweden Democrats for every 1% loss in local population.

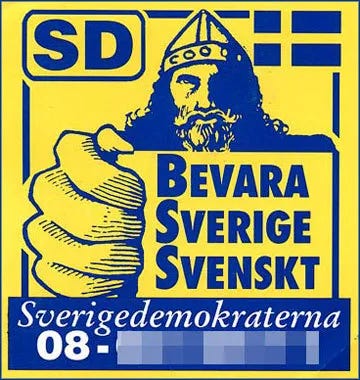

(A Sweden Democrats anti-immigration poster: the semiotics are not subtle. Apart from the Viking schtick and the national colours, the caption says ‘Keep Sweden Swedish.)

They offer two explanations for this. The first is a simple composition effect. Research shows that people who move from peripheral areas to urban areas are more likely to be left-leaning in their politics. The second, however, is that the people who stay shift rightward in their politics because shrinking population means that public services get worse, and this tends to have a knock-on effect on businesses.

In the paper there’s a lot of data analysis, but some of this is summed up in an interview with a former Social Democratic minister:

When discussing the poor rural road conditions, he quips “Every time someone hits a pothole, the Sweden Democrats gain five votes.”

There’s also a loss of status in out-migration areas, which creates status anxiety.

They quote one (Social Democratic Party) mayor:

“someone comes from the outside and says that you’re a failure if you live here … so we are struggling against the public perception of what constitutes a successful individual. We constantly have to work on the psychology of the municipality’s inhabitants.”

In the full paper, they point to research that has associated voting for populists as a response to an individual status, and suggest that this also works at a community level as well:

Prior work has attributed individual-level status loss and social marginalization to radical right voting (Gidron & Hall, 2020). We theorize that emigration can also trigger these feelings at the community level. In short, emigration can have psychological repercussions, which are compounded by material ones.

When centre and centre-left politicians copy anti-immigration rhetoric it risks alienating their political base. And in countries with declining fertility levels and ageing populations, closing borders risks creating a permanent cycle of decline.

A more effective political strategy is to focus on the causes of rural decline, and to try to reverse them, partly by improving public services. The researchers point to some examples:

During recent years, Swedish governments have introduced and gradually expanded a national support system for local commercial services, such as grocery stores, in vulnerable and remote locations. In 2021, Spain announced a US$11.9 billion plan aimed at addressing the lack of 5G telephone connectivity and technologically smart cities in rural areas.

A couple of comments from me. It’s long been clear from straightforward analysis of voting data that populism is a function of areas made more peripheral by globalisation. (I called my 2017 paper on this ‘The City, the Country, and the New Politics of Place’.) Some of this is the other half of the long shift to service economies where value is driven by symbolic knowledge, and this concentrates more value in metropolitan areas. This is a self-reinforcing cycle.

But it also connects to one of the things you see when you look at attitudinal data on Brexit voters and Trump voters in 2016. They are more likely to believe—compared to others—that the future will be worse than the past. Populist politicians play on this. The task of centre and centre-left politicians is to give voters a sense of a future.

2: Grenfell, Aberfan, and the ‘Core Group’

It is the seventh anniversary of the Grenfell Tower fire today, which killed 72 people in Kensington in west London in 2017. (I’ve written about Grenfell here before). Ever since the fire, the folk singer Martin Simpson has committed to singing Leon Rosselson’s song ‘Palaces of Gold’ in every set he performs.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

He says he will continue to do this until the bereaved families, survivors, evacuated residents and the wider local community get justice. The last time I saw him play, he introduced the song by saying, “I wish I didn’t have to play this today”—meaning, of course, that he’d hoped that by now that they might have got justice.

‘Palaces of Gold’ was written by Leon Rosselson, a radical song-writer and performer, in response to the Aberfan tragedy in Wales in October 1966. A mining spoil tip slid down the mountain and engulfed the local school and a row of houses. 116 children and 28 adults were killed.

The song is not specifically about Aberfan. Instead Rosselson focuses on the difference between the lives of the privileged and those of the marginalised. If the children of judges and company directors had to go to school in a slum school,

Buttons would be pressed/ Rules would be broken.

Strings would be pulled/ And magic words spoken.

Invisible fingers would mould/ Palaces of gold.

Simpson first recorded the song in 2013, and it was in his repertoire from time to time before the Grenfell Fire. But as he said at a gig early this year, if he plays it until the Grenfell families get justice, he’ll probably still be playing it when he is 135.

Simpson’s use of a song about the Aberfan disaster to keep Grenfell in the minds of his audiences creates some instructive comparisons.

At Aberfan, the community had been warning the National Coal Board that the spoil tip was dangerous for some years, and they were treated dismissively. The National Coal Board disregarded the risks from the tip. The Aberfan Tribunal found that “the Aberfan disaster could and should have been prevented”, as it blamed the National Coal Board for the tragedy.

As the Tribunal inquiry team wrote in the introduction to their report:

the Report which follows tells not of wickedness but of ignorance, ineptitude and a failure in communications.

But it also noted that,

much of the time of the Tribunal could have been saved if ... the National Coal Board had not stubbornly resisted every attempt to lay the blame where it so clearly must rest—at their door.

If you have been following the Post Office Inquiry in the UK some of this might seem familiar.

At Grenfell, residents who raised concerns about the cladding and the fire safety arrangements at Grenfell were ignored, or even targeted by the Council’s Tenant Management Organisaton. The housing journalist Peter Apps wrote in his must read piece after the inquiry closed that not one organisation, in the public or the private sector, did what it should have done by the residents of Grenfell, at any stage in the process:

In the private sector there was a callous indifference to anything – morality, honesty, life safety – that was not related to the bottom line of the business. In the public sector there was an aversion to anything that disrupted the status quo, a weary cynicism and an insular desire to protect the reputation of organisations by refusing to admit or actively concealing flaws.

The Grenfell Inquiry also explored, in effect, the systems idea that organisational systems produce the outcomes they are designed to produce, even if these are poor outcomes, while people inside them think that they are decent people who are just doing their jobs. Abbs says:

As Danny Friedman QC, one of the barristers for bereaved and survivors, said: “Everyday moral restraints make it hard for people, especially public servants, to admit inhumanity or comprehend that inhumanity is not restricted to bad people. And yet, it occurs in bureaucracies and businesses when basic moral restraints become neutralised or otherwise compromised.”

This reminded me of Art Kleiner’s fine book The Core Group which I wrote about on my blog at the time of the Barclays scandal in 2013. His theory is that all organisations have a core group—not always the Board—whose views of what the organisation is, and what matters to it, is communicated to the rest of the business in such a way that they act on it.

In the Inquiry into Britain’s Post Office scandal, for example, we have heard repeatedly how the stated and implicit views of the Core Group about both the general untrustworthiness (and low status) of sub-postmasters, and the underlying integrity of Fujitsu’s Horizon software, spread to everyone they touched, even though both of these views were fundamentally and disastrously wrong.

As Kleiner writes:

“The organization goes wherever its people perceive that the Core Group needs and wants to go. The organization becomes whatever its people perceive that the Core Group needs and wants it to become… If a goal is perceived as irrelevant, no matter how worthy it is, no matter how ardently it is advocated, or even how stringently it is mandated by law or regulation”.

The Grenfell case still has some way to go. The inquiry report is due to be published on 4th September, and after that the police will need to review all of the inquiry evidence to work out what it adds to their already large-scale investigation, before making recommendations to the Crown Prosecution Service. If people are charged as a result, it won’t be until late in 2026.

(In the meantime you’ll certainly have time, if you want to, to read Andrew O’Hagan’s monumental book-length piece on the tragedy, published by the London Review of Books a year after the fire, and currently outside of its paywall.)

The Met are under some pressure here. They currently have a Core Group problem too. As Apps says in his article,

if the Metropolitan Police is to have any hope of a relationship of trust with the working class communities of London, it must show that it is willing and able to prosecute the people responsible for the deaths of a community like them in Grenfell Tower.

In the meantime, Martin Simpson will have to get used to singing Palaces of Gold every time he goes onstage.

(Photo: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

j2t#581

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.