23 May 2024. Migration | Systems

Changing the ‘toxic’ discourse on migration // Understanding systems thinking [#573]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Changing the ‘toxic’ discourse on migration

I’m so pleased to say that the Rethinking Migration and Mobility report that I co-wrote for the International Organisation for Migration has been published. My fellow authors are my SOIF colleagues Paul Raven and Iman Bashir.

As I think I have mentioned here before, Iman and I facilitated a workshop with a group of migration experts in Istanbul in October, which provided an initial set of ideas for the report, which we then developed with some supporting research and analysis.

The report can be downloaded here.

In this Just Two Things, I’m sharing a version of the section of the report on the challenge of making migration a less toxic political issue. It’s a bit more academic in style than the usual pieces in Just Two Things.

The road ahead: a (geo)politics of migration

Because parties and politicians across the world make political capital out of migration, the public and political discourse around migration is routinely described as “toxic”. In a recent article about the narrative construction of “migration”, Sommer (2022) notes that

pragmatic policy narratives of crisis management clash with aggressive discourses of xenophobia and racism, cosmopolitan counter-narratives and the humanitarian storytelling employed by NGOs.

Over the last decade, though, it is these populist and “xenophobic” discourses on migration that have been normalized by the mainstream. These play out in public attitudes. More than with any other policy area, there is a chasm between what the data tell us about migration, and what people believe to be true about it. In a survey of six developed countries,

respondents greatly overestimate the total number of immigrants, think immigrants are culturally and religiously more distant from them, and economically weaker – less educated, more unemployed, and more reliant on and favored by government transfers – than they actually are (Alesina et al., 2022).

This fits with a perspective which says that the rise of global populism is a reaction to two things: the over-reach of globalization in the 1980s and 1990s, and a long secular shift in generational values.

Alesina et al. say “there is compelling evidence, from a variety of settings, that globalisation shocks, often working through culture and identity, have played an important role in driving up support for populist, particularly right-wing, movements.” This also positions “reimagining of migration and mobility” as a fundamentally political project.

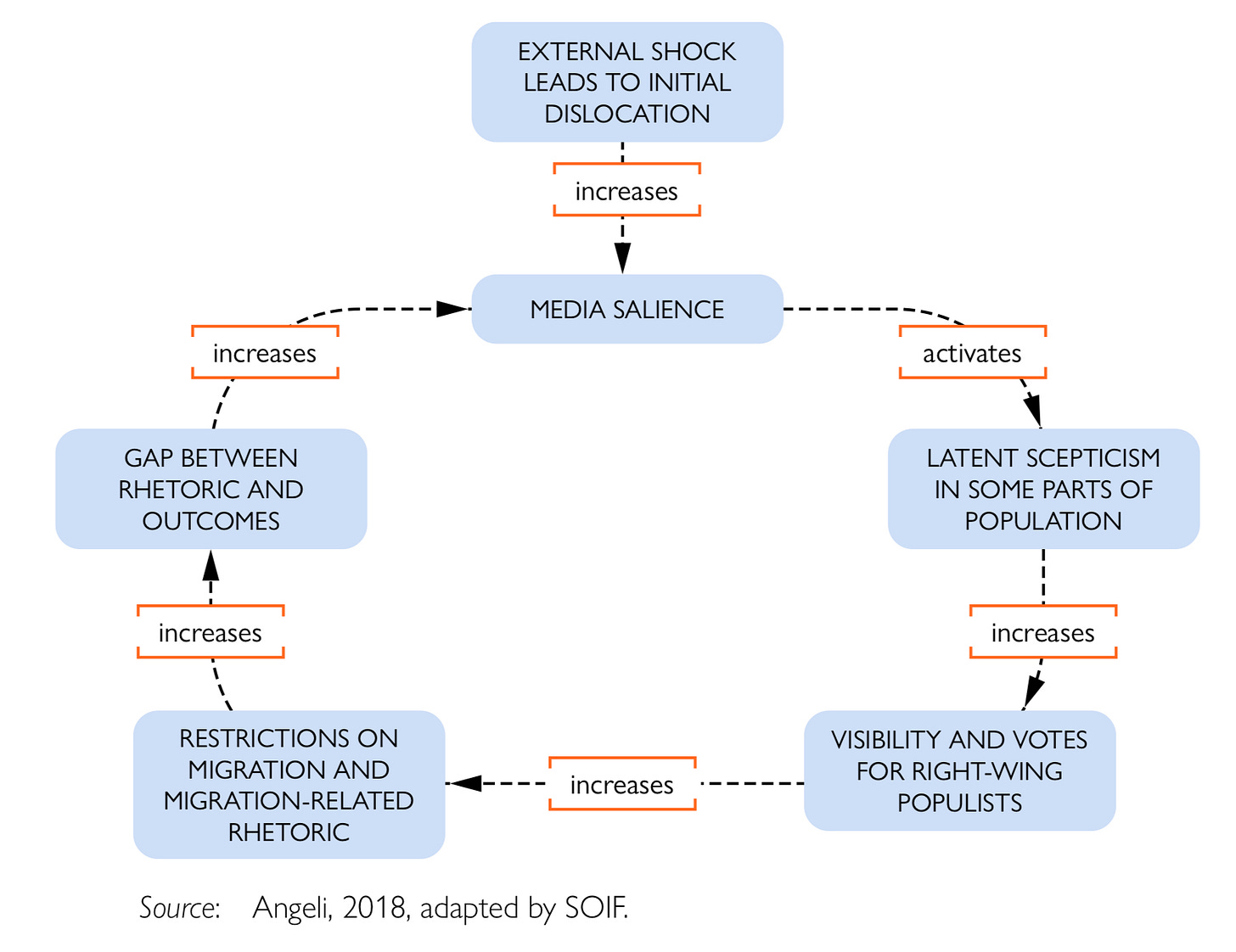

Processes therefore matter. Different political and media actors are enrolled at different moments in a cycle that uses migration to feed right-wing rhetoric (see figure). External shock leads to an internal dislocation of some kind, which becomes a media subject in traditional and social media.

This then feeds through into the political system, at the level of both rhetoric and regulation (Angeli, 2018). Since migration is a necessary part of well-functioning labour markets, however, there is always a gap between the rhetoric and the outcomes.

Figure: The vicious cycle of migration discourse

Recent behavioural research has focused on the construction of the underlying schema of “migration as crisis” that sits behind this cycle. Taking the Ukraine war and the Afghanistan evacuation as examples, Cantat et al. (2023) observe that migration is not always a “crisis”. The activation of that particular framing is always a choice.

On this reading, “migration” and its “control” become an expression of deeper anxiety about the control of the State, at both a national level and an individual level. This “crisis” framing is then expressed through rhetoric about “control” and “containment” that is always incomplete. This is the policy cycle that sits behind the political cycle in the figure above.

These narratives

rely on the assumption that migration is not (or should not be) a normal phenomenon... This blocks the recognition of migration as a structural feature of today’s world, and the elaboration of long-term, systemic political strategies.

Migration, then, which became an issue with the development of the modern nation-state in the twentieth century, has become a signifier of a whole range of problems experienced by the twenty-first century state.

This suggests that rethinking migration requires strategies that can operate at two levels. There is the immediate challenge of finding ways to break the political cycle; then there is a deeper challenge, which is to detach the notion of “migration” from the deeper anxieties for which it has become a proxy.

Changing the narrative

Battles over narratives are typically also battles over political frames. Lakoff (2004) characterizes the difference between conservative frames and progressive frames as being expressed in metaphors about the family. Conservative ideas stem from a notion of “the strict family”; progressive ideas from a notion of “the nurturant family”.

These conflicting sets of ideas can also be seen in the frames deployed against modernity and for it, by authoritarians and populists and their political opponents respectively, as discussed earlier. Clearly the current discourse about migration comes from “the strict family”.

In Lakoff’s description, the values that sit behind the nurturing family include freedom, opportunity, prosperity, fairness, community-building and trust. The advantages that flow from migration – economic, sociocultural and civic–political – resonate strongly with these values. They also underpin a different narrative about the purpose of the state. They speak beyond migration to tell broader stories to all citizens about the role of a supportive and infrastructural twenty-first century form of government.

As Sommer (2022) says, “The pro-migrant narrative and the anti-migrant narrative are incommensurable.” Reframing involves telling your story on your terms, rather than trying to argue with opponents on their terrain, which serves only to make their argument resonate more strongly. In the words of Alesina et al., “views on immigration are more sensitive to salience and narratives than to hard facts.”

The challenge of reframing, therefore, is to build a base that is willing to speak for migration in narratives that progressive and centrist voters can support. Since part of the politics around migration is a response to globalization, this cannot only be done top-down by global institutions. However, local activist groups get lost in the noise; the contrast between

well-funded and organized anti-migration parties and the bootstrapped community groups that seek to defend refugees and migration could not be sharper.

Filling this gap requires a serious coalition-building project – bridging the local, the national and the international. One successful precedent would be the peacebuilding project, which brings together concerned scientists and technical experts with religious groups such as the Quakers that work both locally and globally.

This is slow work. As Lakoff reminds us, when your opponents have control of the frame, it takes time to build a different version of it; but there is a political audience for this story and it is likely to grow as time passes. Migration politics is at its core a struggle over values, and the values of the younger generations are much more aligned with the story of opportunity, fairness and trust.

There is also a playlist that was developed during the workshop and curated by Iman afterwards.

Alesina, A., A. Miano and S. Stantcheva (2022). Immigration and redistribution. NBER Working Paper 24733.

Angeli, O. (2018). European migration policy and the rise of populism. European Insights.

Cantat, C., A. Picoul and H. Thiollet (2023). Migration as crisis. American Behavioral Scientist.

Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t Think of an Elephant! Chelsea Green, White River Junction, Vermont.

Sommer, R. (2023). Migration and narrative dynamics. In: P. Dawson and M. Mäkelä (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Narrative Theory. Routledge, New York.

Understanding systems thinking

I’m a member of the Agri-Foods for Net Zero network, and it runs a good series of knowledge sharing events. (I’ve written about AFNZ here before). Earlier this week, it invited one of Britain’s leading systems academics, Gerald Midgeley, to do an introductory talk on using systems thinking to explore complex problems.

All of the images here are courtesy of Gerald Midgeley, who generously shared his slides after his talk. AFNZ has also shared a video of the talk online.

The questions he addressed were:

What are highly complex problems?

What is systems thinking?

Different systems approaches for different purposes

Highly complex problems involve many interlinked problems, involving multiple agencies, with different views on the problems and the potential solutions. There’s conflict about preferred outcomes, preferred means to those outcomes, and power relations that make change difficult. There’s also uncertainty about the possible effects of action.

The focus of the talk was on using systems to address complex problems in the context of policy and management ideas. Although he has been working in this area for decades, he thought there had been a tipping point in 2017, when the United Nations, World Heath Organization and the OECD called for a systems approach to join up the sustainable development goals.

There are, he said, three dimensions to thinking. These are: in your head; thinking with other people (which is what we use language for); and feedback with the material world. He also observed that thinking and emotion are part of one cognitive system. Every thought is accompanied by a feeling that is accompanied by an emotion.

Our thinking is also fundamentally anticipatory—what we see around us is shaped by what we think is going to happen, and this is based on our past experiences. This is the most efficient way to think, but it also leads to partial interpretations of the world.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

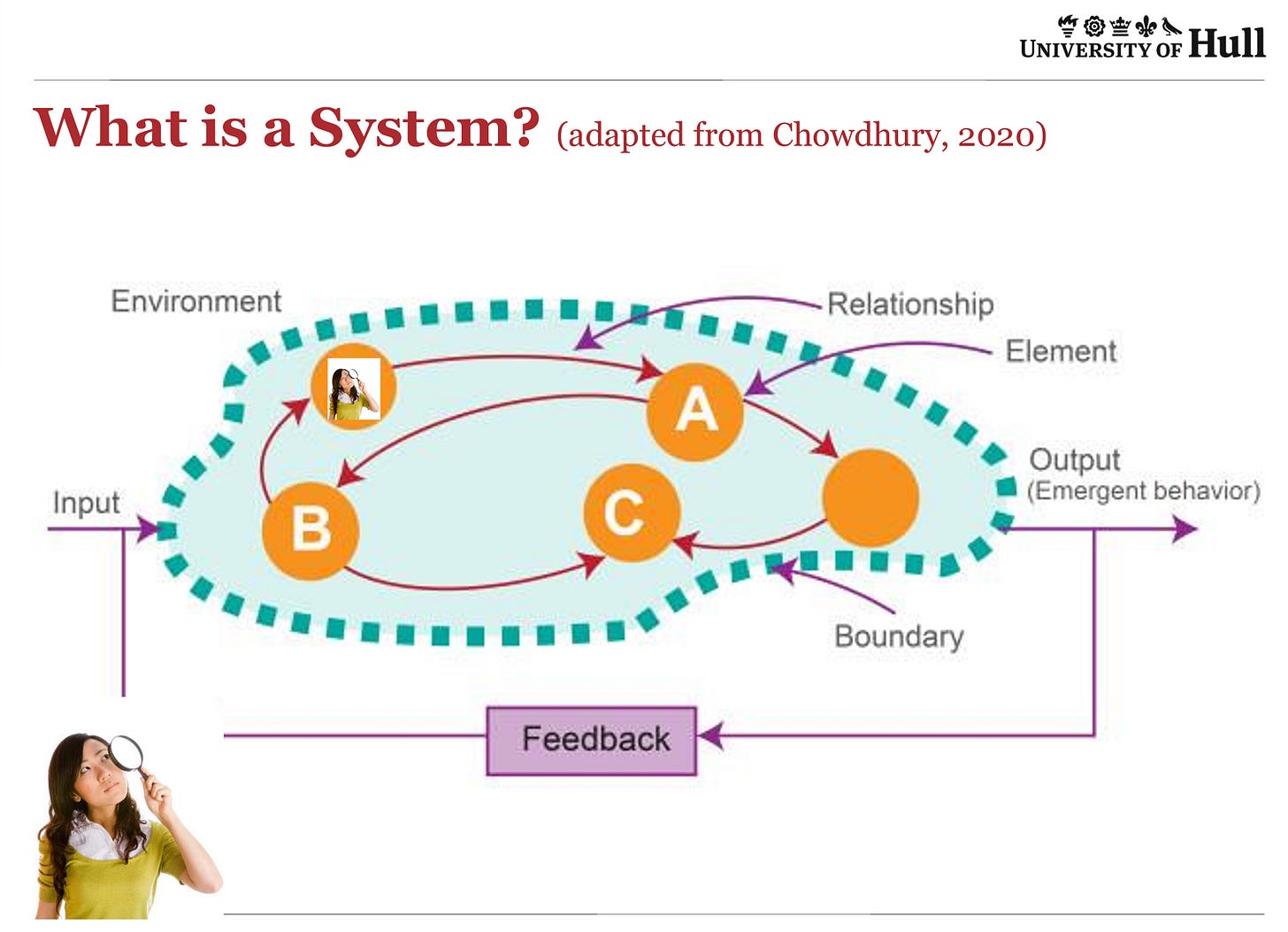

A system has inputs, outputs, boundaries, and relationships between the elements. A system also has feedback. We can say what is inside and outside of the system, but boundaries are always seen from the particular perspectives of people in the system. And: we always see a system from its inside despite the image in the picture of the woman looking at the system from outside. She is there as a pedagogical point about the impossibility of doing this.

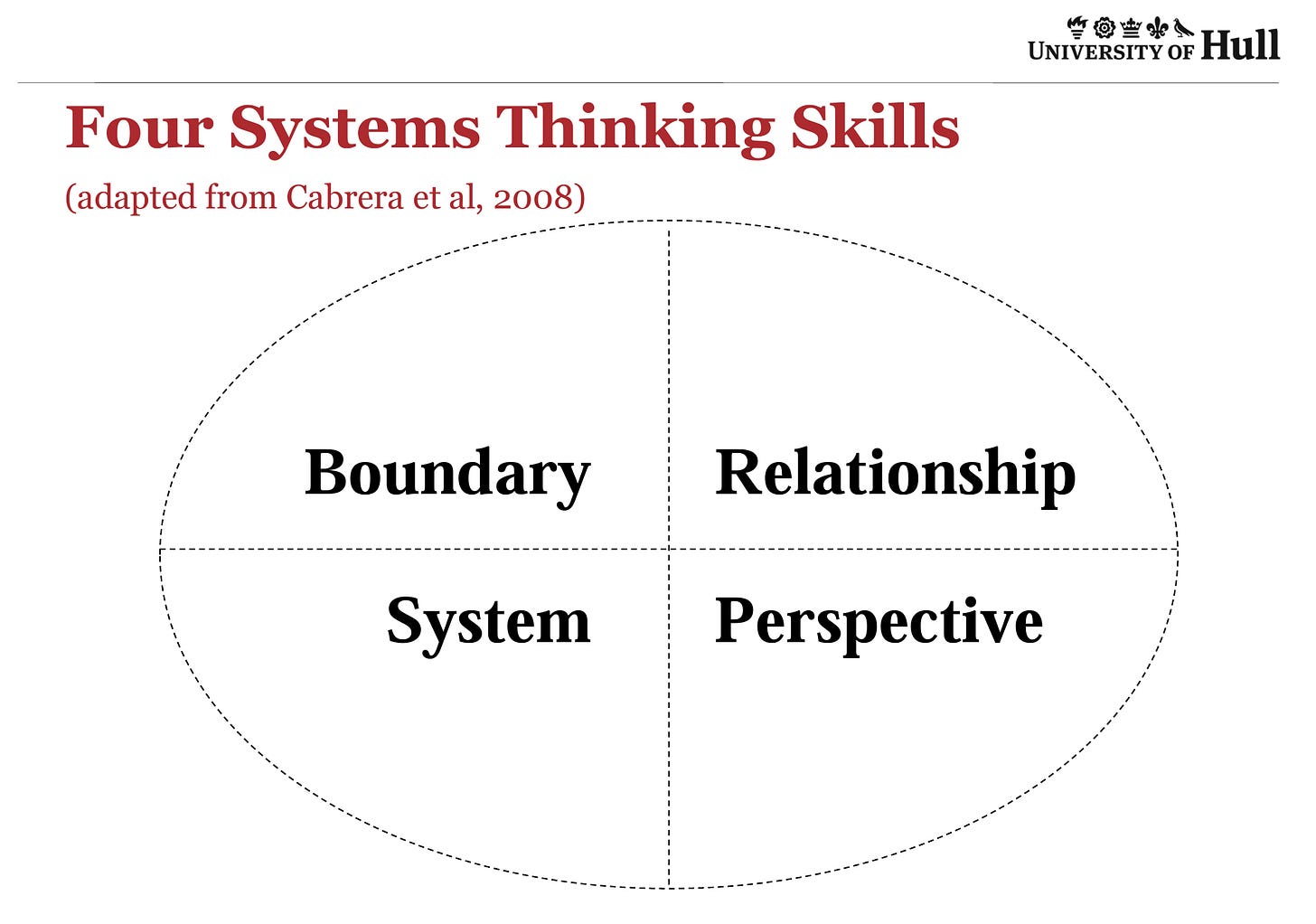

The talk was structured around a framework of systems thinkings skills adapted from the work of Derek and Laura Cabrera. Each of the four was used to introduce a different approach.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

The Cabrera framework helps you to map different approaches. Each element tends to focus on different parts of the system. And Midgeley used each one of them to introduce a different element of systems thinking.

1. Boundary critique

Boundaries are about inclusion and exclusion. Those inside have views on “what could or should be done” — which often constrains views on what can be done. Conflicts over boundary judgments are common, but they also point you to areas of common concern.

Midgley gave an example of this from some work one of his students had done in Nigeria over waste reduction. There was conflict with a food production company over the dumping of animal effluent, exacerbated by an unreliable energy supply. The community had got the government involved, which was fining the company for breaching waste regulations.

As a result of this conflict the company had halted expansion plans, to limit the scope for further disputes. The systems research drew a bigger boundary around this. The animal waste was reimagined as a source for biogas, which in turn ended the energy issues. A viable biogas plant needed more animal waste, and the company found that there was a market for much more production, creating jobs in the community and increasing its profitability.

2. Complex causal relationships

Midgeley shared a systems dynamics diagram at this point, pointing to the work of Jay Forrester. Of course, they are hard to read, but they are not designed as communications devices: that’s not the point of them. They are there, in effect, as boundary objects (my phrase, not his) to help groups who have a shared interest in a system understand their relationships.

Midgeley worked in New Zealand for a number of years, where there was a question about why the country had high rates of food poisoning. One claim was that it was caused by the levels of animal waste in the water. In New Zealand anything that involves the dairy industry is a big deal: it represents more than half of the country’s exports.

His brief was not to solve the food poisoning issue, but to get the two sides talking. He got them to build their own causal maps, at which point they were willing to talk to each other. Rather than getting them to justify their maps, he asked them to walk the room and look for the things that connected their diagrams to others.

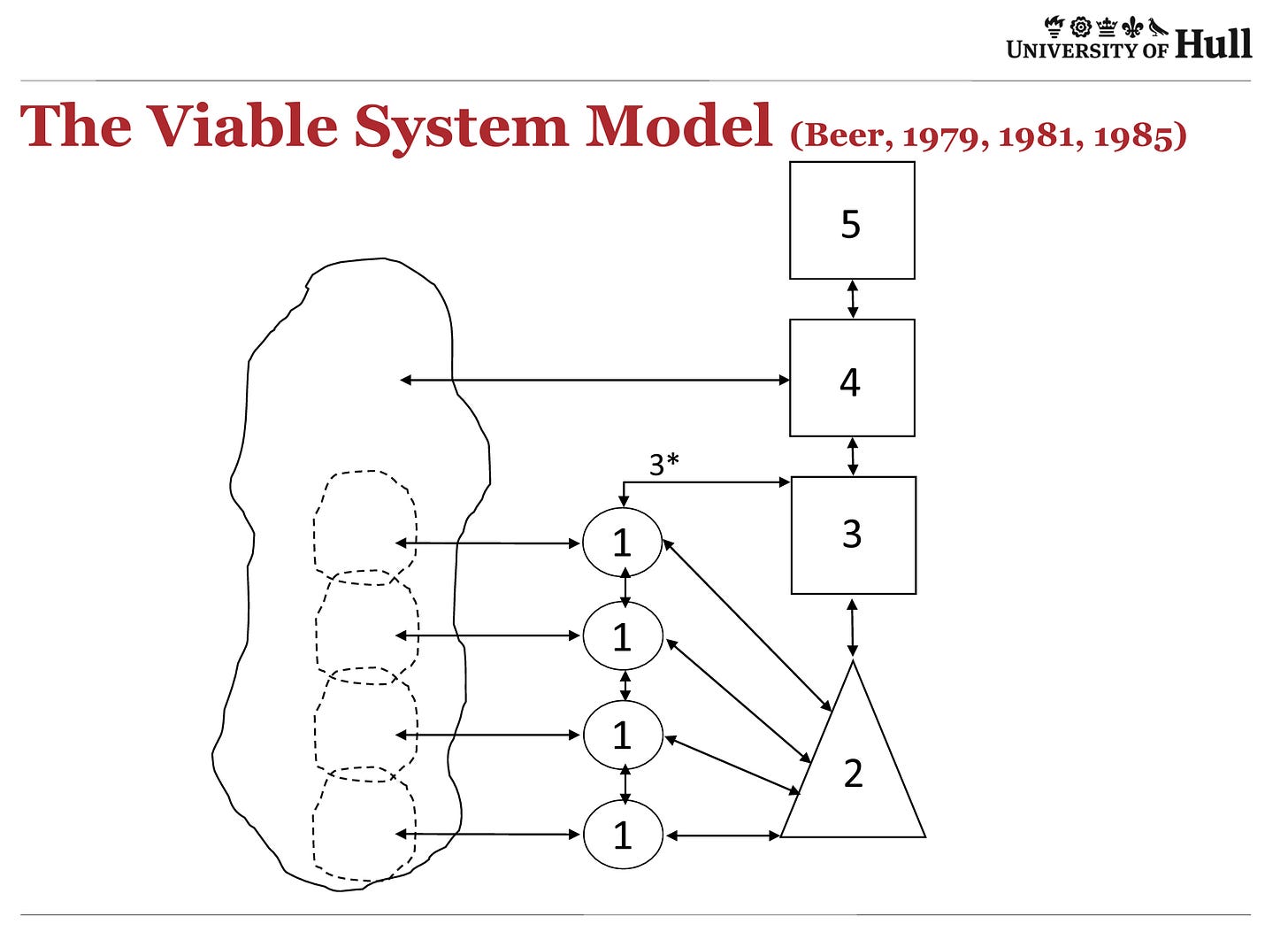

3. System

The system quadrant was pegged to Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), which he developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. (I wrote about the VSM in Just Two Things here; and about Stafford Beer more recently). This probably does need a diagram.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

There’s much more to this, but in brief, every organisation has an environment it interacts with. The VSM imagines the organisations as five types of system element. System 1 is the operational units—in his example, of a hospital during COVID, these are the wards, the operating theatres, and so on.

Operational units need some system of co-ordination, which is System 2–resourcing the staff, ensuring patients are routed to the right wards, and so on. System 3 is day-to-day management, monitoring operational performance — which is done by monitoring it and letting it run while performance runs between the normal levels of variance, and getting involved, in Beer’s phrase, only “by exception”.

System 4 is foresight—looking at threats and opportunities—while System 5 is about purpose and identity, the ethos of a system.

In the talk there’s a striking example of this approach being used by Pam Sydelko to redesign the system in Chicago under which different agencies engaged with international organised crime and local gang violence. Being good at local gang violence—killing people—was the best way to get recruited by one of the much more lucrative international gangs. The gang systems were related but the agencies weren’t.

4. Perspective

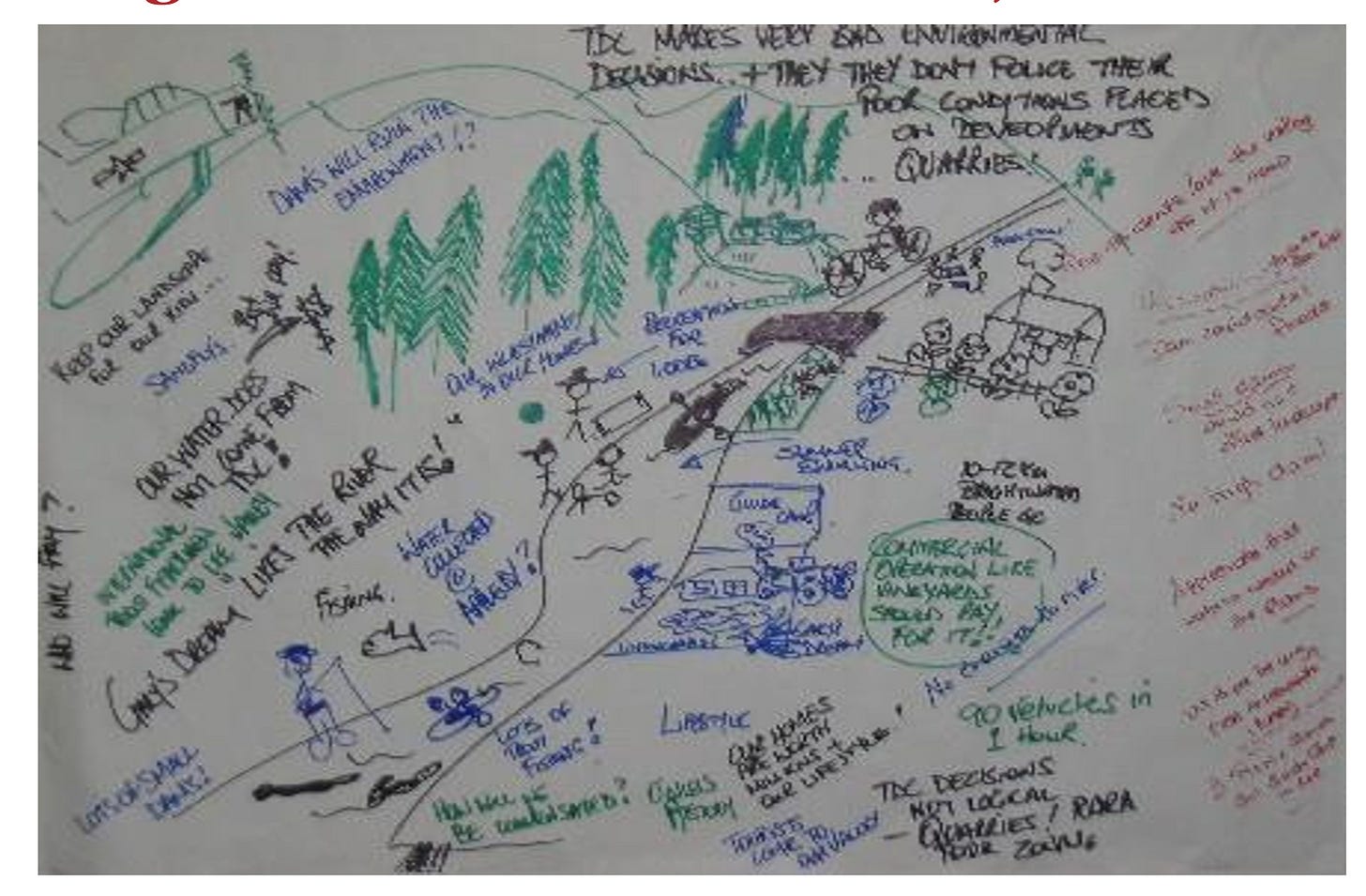

He used ‘perspective’ as a way to talk about Peter Checkland’s soft systems methodology. This proceeds by getting participants to draw a rich picture of the system, including the places where they disagree. There was an example of a rich picture in one of his slides.

(Source: Gerald Midgeley)

Checkland developed an acronym for the elements you needed to identify what was going on in a soft system, which Midgeley had adapted. He used ‘BATWOVE’, standing for Beneficiaries, Actors, Transformation, Worldview, Owners, Victims, Environment (or ‘external’) constraints.

(I don’t have space to go into this here, but there’s a good paper by Bob Williams online that explains both Checkland’s methodology and Midgeley’s evolution of it.)

The rich pictures map the activities and the agents involved in each transformation, and then look for what he called “accommodations”, and agree changes. He uses “accommodation” rather than “compromise” makes people defensive, and “accommodations” may be a new idea that comes out of the process.

Finally, in response to one of the questions, he talked about “the myth of ‘comprehensive understanding’. The point of systems work is to understand where there is a lack of comprehensiveness and comprehension.

The hour-long talk, and the questions that follow, can be seen on YouTube here. It is concise and well-structured:

j2t#573

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.