13 August 2024. Politics | Writing

The construction of minorities—and majorities // The strange tale of the 1924 Olympic writing competition [#595]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The construction of minorities—and majorities

The third post in a series trying to understand the recent riots in England and Northern Ireland. Number one is here; number two is here.)

If we’re going to talk seriously about the recent riots in England and Northern Ireland, we need to talk about the construction of racism, and the idea of ‘majorities’ and ‘minorities’.

Because: the riots had a clear racist intent. As the historian David Olusoga pointed out, “most of those targeted by the rioters were British citizens”.

But one of the things about the riots—as with the Brexit vote in 2016–is that it projects racism outwards: it legitimates racist behaviour.

For example, I have on my phone several messages from a friend who runs a public sector delivery organisation in the north of England, with examples of what this is like in practice. Here’s one of them:

One of my call centre staff was on her way to work one morning this week in a niqab, and six men came up to her in a petrol station and threatened with a petrol pump to pour petrol all over her.

In an article in the Guardian, David Olusoga runs through the history of white racist riots in the UK. In 1919 in Liverpool, Cardiff, Glasgow, London, Salford, Newport, Barry, Hull and South Shields; in 1948 in Liverpool; in 1958 in Notting Hill in London.

The grievance that brought them on to the streets was the presence in their cities of non-white people.1

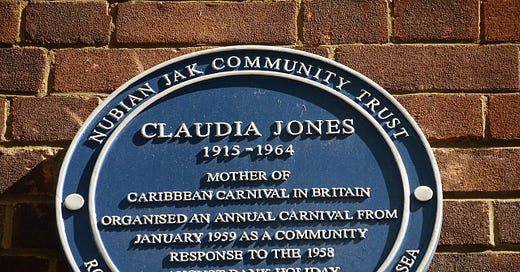

(The Notting Hill Carnival was set up as a direct response to the 1958 race riots in the area. Photo: Edwardx via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

The journey from there to here runs through the English politician Enoch Powell, and a series of interviews and speeches about immigration during the 1960s, culminating with a notorious speech in 1968 now known as as the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. This was made while the Labour Government’s 1968 Race Relations Bill, which outlawed some forms of racial discrimination, was going through the legislative process.

Part of Powell’s speech recalls a conversation with a constituent—who may have been real or may have been a rhetorical device. This “decent ordinary fellow Englishman” (my emphasis) had told Powell, apparently, that "In this country in 15 or 20 years' time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man".2

You don’t need to be a semiotician to understand what is going on here.

In his 2006 book Fear of Small Numbers the social scientist Arjun Appadurai explores how ideas of “majorities” and “minorities” are constructed. He argues that this is essentially the creation of the modern bureaucratic state:

Both minorities and majorities are the product of a distinctly modern world of statistics, censuses, population maps, and other tools of state... [M]inorities are a recent social and demographic category. [p41-42]

Minorities, therefore, are not a general social category. Instead, they are constructed through the specific circumstances and specific histories of different countries. From this analysis, Appadurai builds out a category of “predatory majorities”, which emerge in the gap between majority identities and national identities.

Such majorities make claims both about culture and about a threat that they might themselves become a minority. The Scots political theorist Tom Nairn discusses how Powell played on the notion of “the old English” even as he became obsessed by immigration.

Now, Appadurai is interested in how genocidal and ethnocidal attacks emerge within societies. All the same, the rhetorical strategies of “predatory majorities”, and their violent intent, can be seen in the ways in which racist violence is mobilised. Indeed, the Great Replacement Theory, which I wrote about last week, is a conspiracy theory about replacing a majority population with a minority one.

Minority populations can be presented as problematic in a number of ways, as Appadurai spells out:

Their movements threaten the policing of borders. Their financial transactions blur the lines between national economies and between legal and criminal transactions. Their languages exacerbate worries about national cultural coherence. Their lifestyles are easy ways to displace widespread tensions in society, especially in urban society. [p45]3

Another important element of the racist narrative is about notions of masculinity. There are some contradictions here. On the one hand, as Pankaj Mishraj writes in an essay about Jordan Petersen called ‘The Lure of Fascist Mysticism’,

these hyper-masculinist thinkers saw compassion as a vice and urged insecure men to harden their hearts against the weak (women and minorities) on the grounds that the latter were biologically and culturally inferior.

On the other, the women, at least the white women, need their protection, as the terrorism researcher Elizabeth Pearson observes in The Conversation:

White supremacy is founded on the narrative of a specifically gendered and racialised threat—the threat from “other” men to “native” women and children… It’s explicit in the so-called “14 words”, the most famous slogan in white nationalism, which urges followers to “secure a future” for white children.

(‘The old English’, or toxic masculinity at work. I wonder what the prompts were. Image by Europe Invasion, collected on Twitter by Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones)).

Because minorities are produced at specific historical moments, they can change over time. One of the striking features of the current racism is that it is clearly Islamophobic, but no-one says this, in the same way that between the wars much British racism was anti-Semitic and this was largely taken for granted.4

Watching the MP Zarah Sultana trying to explain this to an apparently uncomprehending Ed Balls on the ITV show Good Morning Britain, explaining that they involved attacks on mosques, was educational. Even the politician-turned-presenter Ed Balls—who spent most of this exchange talking across her—would have understood that attacks on synagogues were anti-semitic.

The Labour Party’s role in all of this should not be downplayed. Versions of the language of “legitimate concerns”, seen much in the last couple of weeks, has a long history when it comes to justifying racism. As Home Secretary in the 1960s in the wake of Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, James Callaghan rushed through the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which removed automatic right of entry to the UK for Asian British passport holders.

At the same time, the Labour government pushed through the Race Relations Act.

But Labour has always been Janus-faced on race, perhaps because trades unions historically made much of (generally mistaken) arguments about immigrants taking the jobs of their members.5 Certainly in London, the people who took to the streets in support of Powell were Port of London dockers and the porters at Smithfield’s meat market.

In response to the recent riots, the Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, has treated them as a policing issue, rather than taking the opportunity to affirm the party’s support for the communities that came on to the streets to defend their neighbours and public buildings from attack.

Indeed, Nick Thomas-Symonds-Thomas, the Cabinet Office minister, appeared on television to discourage such shows of community action, apparently because they would cause policing problems. (You have to think about this for a minute, because they clearly cause fewer problems than allowing violent racists to riot unchecked.)6

As Phil Burton-Cartledge noted on his blog, it seemed that King Charles was doing more than Starmer to support these communities. This is from a Buckingham Palace release of details of calls between the the King, the Prime Minister, and police leaders:

The king shared how he had been greatly encouraged by the many examples of community spirit that had countered the aggression and criminality from a few with the compassion and resilience of the many.

Being outflanked to the left by the King takes some doing.

And here is the so called ‘Blue Labour’ researcher Jonathan Rutherford, writing in the New Statesman and using language that could have come from Samuel Huntington. Well, you can judge for yourself:

For the first time in national history, people are living alongside others with radically different civilisational values. Avoiding deeper conflict requires a confident society supported by a strong state capable of controlling the numbers of newcomers, ensuring their integration, and resolving differences through reciprocal agreement of the common good. This is not England today.

I don’t recognise this description of Britain, and if I’m being honest I don’t associate these sentiments with social democratic politics either. This is Powellite sentiment dressed up in slightly more neutral language.

We have been here before. In the late 1970s, when the far-right National Front and the British Movement surged in the polls and on the streets, the response was the creation of two activist organisations, the Anti-Nazi League [ANL] and Rock Against Racism [RAR]. The Anti-Nazi League was a political organisation that would also face off against the far right on the streets; Rock Against Racism did festivals and concerts.

(‘Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard. But…’ Poly Styrene at the Rock Against Racism festival in Victoria Park, 1978. Photo: Andy Wilson/ flickr. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Of course, you can’t step in to the same river twice. The moment changes as politics, culture and technologies change. The closest we have now to the ANL and RAR is Stand Up To Racism, which organised some of the community events last Wednesday. (I am not using the term “counter-protestors” because that suggests the riots were a “protest”.)

But of these only Rock Against Racism actually celebrated the richness that migration brings. And as long as migration is positioned as a problem, rather than a benefit, we’ll keep on going through this toxic loop. I wrote about this on Just Two Things a few weeks ago (and in a different version also here), and this post is far too long already.

But: in brief, as I wrote there, migration is a structural necessity for modern societies that brings significant economic, cultural, and social benefits. Until we treat it as a positive force in our societies we will see racist attacks surface whenever the political weather shifts. In turn, this requires the construction of a national culture that values the contribution to it of all the cultures within it. And which tells its own story about the benefits of this.

2: The strange tale of the 1924 Olympic writing competition

The 1924 Olympics in Paris saw the most serious attempt to run a literature competition alongside the sporting events.

The story has been retold in an essay, Les Jeux Olympiques de littérature, by the French writer Louis Chevaillier, and an article by Paco Cerda in the Spanish newspaper El Pais gives it the literary flourish it deserves.

There had been literature competitions before, but hardly anyone entered and one time the founder of the modern Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin, had won under a pseudonym.

But in 1924, in Paris, it was different. For one thing, the 30-strong jury was heavyweight. It included two Nobel Prize winners, the Belgian author Maurice Maeterlinck and the Swede Selma Lagerlöf, the first woman to win. Paul Valery was on the jury. So was the ultranationalist ‘fascist whirlwind’ Gabriele d’Annunzio, and the republican and anticlerical Valencian writer Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, exiled in France by General Primo de Rivera. The American writer Edith Wharton was on the jury as well. The discussions must have been a blast.

The challenge set for the entrants:

Twenty thousand words of prose or 1,000 verses. There are three Olympic medals at stake and too many dreamers are competing for them: writers enlightened by the ideal — whatever it may be — in a time drunk with ideals.

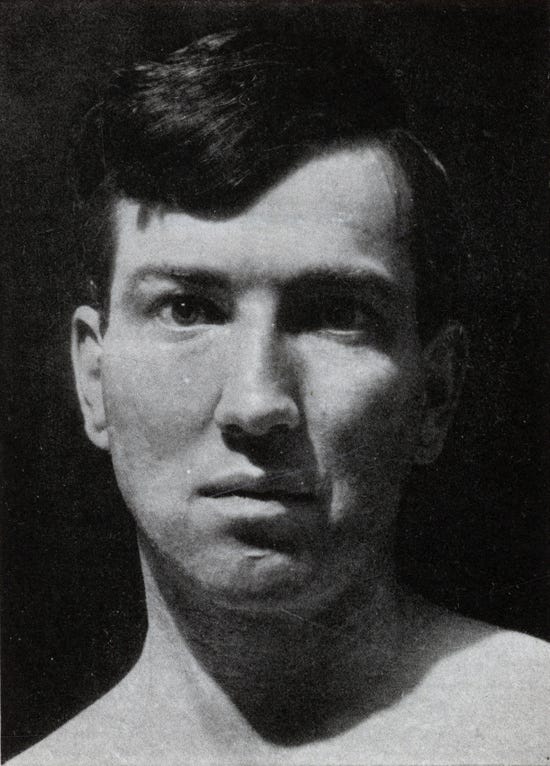

32 writers from 10 countries answered the call. They included Robert Graves, largely unpublished and still recovering from the injuries and the post-traumatic stress of his wartime service:

To the Olympic test he submits a long poem of 280 lines. It is entitled At the Games and is a dialogue between two old soldiers, an Englishman and a Frenchman, who meet again at the Olympics to watch a boxing match.

The Frenchman says: “War is often a sport.”

The Englishman replies: “And sometimes sport is war.”

(Robert Graves in 1929. Photo: Public domain via Picryl)

The connection between sport and war seems to be a theme in the entries, perhaps not surprisingly. Cerda tracks down an old copy of Henry de Montherlant’s Olympic entry, Le paradis à l’ombre des épées, which I’d say translates as ‘Paradise in the shadow of the swords’. It looks like it might be heavy going:

“If the development of every man requires a point of support outside himself, that point of support will be for you the homeland. In the stadiums, by increasing your courage, you prepare yourselves — even unwittingly — to consolidate the fatherland. Through sport you become part of the fatherland without even thinking about it, which is perhaps the wisest way to join it.”

Many of the other entries, judging from their titles, seemed to be in that space where sport and war touched:

Towards the God of Olympia; The Triumph of the Athlete; At the Top; Olympic Odes; Olympic Hymn; Exuberant Youth in the Open Air; To the Glory of Sports; The Land Where the Rose Grows; The Battle; The Glorious Uncertainty.

The winner is the 32-year old Charles Louis Prosper Guyot, who now styles himself as Géo-Charles. Before the war, he had been a football player. He had fought in the French army, been taken prisoner, and spent four years in a German camp.

He writes in magazines, admires Tristan Tzara, has published a book of poems entitled Sports. To the Paris 1924 competition he sends a 70-page book entitled Jeux olympiques, which is a kind of theatrical poetry or poetic theater. It is strange. But the fact is that he wins the gold.

(Geo Charles. Thanks to Antiquariat Steffen Völkel on Abebooks.)

And the Olympic Committee sends him his medal in the post. He is indignant, and sends it back; he thinks there should be an awards ceremony, in the same way that the athletes have.

And the committee has no choice but to organize an official ceremony. Gold for Géo-Charles; two silvers, for the British author Dorothy Margaret Stuart and the Danish novelist Josef Petersen; and two bronzes for the French poet Charles Anthoine Gonnet and the Dublin physician Oliver St. John Gogarty.

Most of these names, of course, are as obscure now as the athletes who won medals in the 1924 Games. And there is a coda. In 1928, Géo-Charles spurns the Olympuc Games in Amsterdam and goes instead to the competing Bolshevik Spartakiades in Moscow:

Géo-Charles will then write that nothing remains of the old social ideal that underlay the Olympic Games.

j2t#595

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

There’s a telling moment in Philippe Sands’ book East West Street where he writes of a moment in 1919 where the League of Nations proposes to guarantee Poland’s independence in exchange for a commitment to protect its minorities. British officials are keen to make sure that this is specific to Poland, as Sands notes: “The new League of Nations must not have the right to protect minorities in all countries, a British official complained, or it would have “the right to protect the Chinese in Liverpool, the Roman Catholics in France, the French in Canada, quite apart from more serious problems, such as the Irish.’”

The speech also included a straight out racist slur word that ‘Boris’ Johnson thought it clever to repeat in one of his newspaper columns more recently.

A recurring claim made by the leader of the right-wing British political party Reform UK, Nigel Farage, is that there are parts of English towns where “no one speaks English.”

As I was reminded watching the 1924 Olympics film Chariots of Fire again, just before the Olympics Games started.

This is a classic example of the lump of labour fallacy.

There are apparently electoral reasons for this, to do with Labour’s rather fragile electoral coalition. This doesn’t mean that it is either the right thing to do or good politics.