5 August 2024. Violence | Weather

‘What’s brought violence mainstream is social media’ // Extreme weather could get worse quite quickly [#593]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: ‘What’s brought violence mainstream is social media’

I have been trying to make sense over the weekend of the street violence that has broken out across England over the last few days. It seems both simple and complicated at the same time.

I’m writing about it here because this is not just an English problem, but one that is far more widespread. (The playbook seems close to that of the right wing violence in Dublin a few months ago.) I’m also using the word English deliberately here, rather than “British”. There are reasons why this in an “English” issue.

((C) Cold War Steve)

A short recap for those who haven’t been following the detail. A man with a knife entered a children’s holiday dance class last week in Southport, in the north-west of England, and killed three young girls (and injured others). He was arrested but not named.

A little while later on Twitter/X, a hard-right influencer claimed that the attacker was “a Muslim asylum seeker called Ali Al-Shakati”, who was on an MI6 watchlist. All of these details are wrong. The accused was named in court as Axel Rudakubana, born in Cardiff or Rwandan parents.

The rumour, however, was widely recirculated by far-right influencers, and this was enough for Britain’s small and loosely affiliated far right to organise attacks and riots in a number of English cities.

But it’s complicated because there are several layers here. (I’m going to have to split the story over two posts).

The first is about social media. The second is about how violence gets legitimated. The third is about how racism is coded and legitimated in societies where outright racism is discouraged but it sits below the surface. The second two will get discussed next time.

And the important point about social media, as Maria Resser said to Carol Cadwalladr in the Observer, is that it has become an engine of violence:

“There’s always been propaganda and there’s always been violence. What’s brought violence mainstream is social media. [The US Capitol attack] on January 6 is the perfect example: people wouldn’t have been able to find each other if social media didn’t cluster them together and isolate them to incite them further.”

Social media

Obviously social media is mostly an outrage machine, especially on Facebook and Twitter/X, and to some extent on TikTok as well. Social media companies make more money from people who are angry than from people who are just shooting the breeze.

The actual organisation of these small, violent groups is done on private platforms like Telegram. But these aren’t big enough to mobilise. For that, you need Twitter/X or Facebook.

The first person who shared the false report about the attacker being a Muslim asylum seeker was a woman called Bernie Spofforth, who is a successful businesswoman turned right-wing conspiracy theorist, according to RationalWiki.

She is a climate denier, an anti-vaxxer, and has been a guest on right-wing media outlets such as GB News and NewsUK’s TalkTV. She has more than 200,000 followers. (In their story, The Times declined to name her, because reasons, apparently. Tortoise Media, hardly a radical outlet, had no similar qualms.)

Of course, there are others in this as well, as the Tortoise Media story pointed out:

The Southport murders triggered a range of disinformation from major accounts on X. The YouTuber Andrew Tate falsely claimed the attacker was an “illegal migrant”, the former boxer Anthony Fowler posted a video saying it was a “fellow from Syria”, while a third account called Europe Invasion said the suspect was a “Muslim immigrant”. These three posts alone have had 26 million views and impressions. None have been removed.

The name “Ali Al-Shakati” was also suggested to Twitter/X users as a trending topic.

You can’t get through this story without mentioning the role of others in spreading this misinformation: Stephen Yaxley Lennon, the “self-styled” Tommy Robinson, currently on the run in Spain from a British court appearance, who also promoted these falsehoods, and his sidekick Danny Tommo. The Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, of course, is in there, hard at work legitimising all of this with barely coded messages.

Where did the information that Spofforth re-posted come from? According to a report in the Daily Mirror:

Fake news website Channel3 Now spread lies about the suspect which led to a horrific attack on a mosque and injured 53 police officers.. .

Channel3 Now, which poses as an American news website on X, reposted the fake claims which were seen by nearly two million users before being deleted. The misinformation was quickly picked up by far-right thug Tommy Robinson, Russian state media, and disgraced influencer Andrew Tate, who told his 10 million followers that an "illegal migrant" had stabbed "six little girls" and told people to "wake up".

'Robinson’ had been de-platformed by Twitter for his racist views, but after Elon Musk bought the platform he restored Robinson to the site. (Who could have anticipated that a racist right-wing billionaire would do such a thing?)

Part of the point of disinformation and misinformation is that it’s hard to work out where it came from. But part of Russia’s political strategy has been to cultivate those in the West who share Putin’s hatred of modernity. Both Farage and Robinson fit on that list. Modernity includes multi-culturalism and diversity. Farage has repeatedly said admiring things about Putin. Robinson has been invited to Russia in the part by senior officials. You can decide for yourself whether they are fellow travellers or useful idiots.

(C) Cold War Steve)

We see similar connections (and Putin fanboys and fangirls) among the more Trumpist members of the Republican party.

As Carol Cadwalladr notes in her article, Russia’s role in this has broadly been ignored in the UK by both government and most media. And while people have been warning for some time that far-right extremism is a serious threat, they haven’t yet seen it as a structural problem:

[A]lthough the UK authorities in theory understand these threats – in 2021, the head of MI5, Ken McCallum, described far-right extremism as the greatest domestic terror threat facing Britain – the fundamental technological issues have not been addressed... And there is still little acknowledgment that what we are witnessing is part of a global phenomenon – rising populism and authoritarianism underpinned by deep-rooted structural changes in communication.

I’ve seen many people—including the Prime Minister— describe the violence in our towns and cities over the past days as ‘mindless’. It isn’t mindless. It is meant to make ethnically mixed communities, and people of colour who live in England feel unsafe. It is supposed to be destabilising. I’ve seen it suggested on Twitter that the timing—a month after the election of a government that doesn’t include people who routinely ‘dogwhistle’ to the far right—isn’t accidental either.

What would addressing the fundamental technological issues look like? So far, platforms such as Twitter/X have escaped much in the way of regulation because of arguments about freedom of speech.

But safety—individual safety and public safety—is at least as important, and regulating for this would be a start, perhaps, for example, by slowing down the speed at which content can be shared to reduce its impact. Christopher Wylie, who contributed to this report told the BBC,

If we took the premise that people should have a lawful right to be manipulated and deceived, we wouldn't have rules on fraud or undue influence. There are very tangible harms that come from manipulating people.

Charles Arthur, in his book Social Warming, suggests that one approach to this is to limit the size of social networks—to reduce scale.

Jamie Susskind, the author of The Digital Republic, suggests something similar, that we should focus on “the reduction of the risk of harm.” Modest community platforms would benefit from light-touch regulation. Larger platforms, which pose ‘systemic risks’, would be regulated “at the systemic or design level,” and judged on their outcomes.

The UK Online Safety Act, 2023, in theory is supposed to penalise “sending false information intended to cause non-trivial harm,” which in theory ought to cover Bernie Spofforth. It probably doesn’t have enough teeth. Rewriting Acts of Parliament is time-consuming. But regulation with more teeth might be a start.

2: Extreme weather could get worse quite quickly

There’s a piece in The Conversation that suggests that the climate is currently changing so quickly that we haven’t really started to see the kinds of extreme weather than it could bring with it.

'Climate’ is defined by scientists as “the distribution of possible weather events observed over a length of time”. Typically the length of time is a 30-year period, updated every decade:

From this they construct statistical measures, such as the average (or normal) temperature. Weather varies on several timescales – from seconds to decades– so the longer the period over which the climate is analysed, the more accurately these analyses capture the infinite range of possible configurations of the atmosphere.

Obviously rapid change makes such statistical measures unreliable. This has two implications. First, the distribution of weather events changes from the beginning of the climate period to the end:

[F]or example, northerly winds in the 1990s were much colder than those in the 2020s in north-west Europe, thanks to the Arctic warming nearly four times faster than the global average. Statistics from three decades ago no longer represent what is possible in the present day.

Second, it means that past weather extremes are no longer a reliable guide to the extremes that we might face today:

In a stable climate, scientists would have multiple decades for the atmosphere to get into its various configurations and drive extreme events, such as heatwaves, floods or droughts... But in our rapidly changing climate, we effectively have only a few years – not enough to experience everything the climate has to offer.

The reason for this is that extreme weather events—sort of by definition—require unusual combinations of meteorological conditions that simply don’t happen very often.

For example, extreme heat in the UK typically requires the northward movement of an air mass from Africa combined with clear skies, dry soils and a stable atmosphere to prevent thunderstorms forming which tend to dissipate heat. Such “perfect” conditions are intrinsically unlikely, and many years can pass without them occurring.

The result of this is that we can be unprepared for novel combinations of conditions that generate weather outcomes that we haven’t seen before. One recent example:

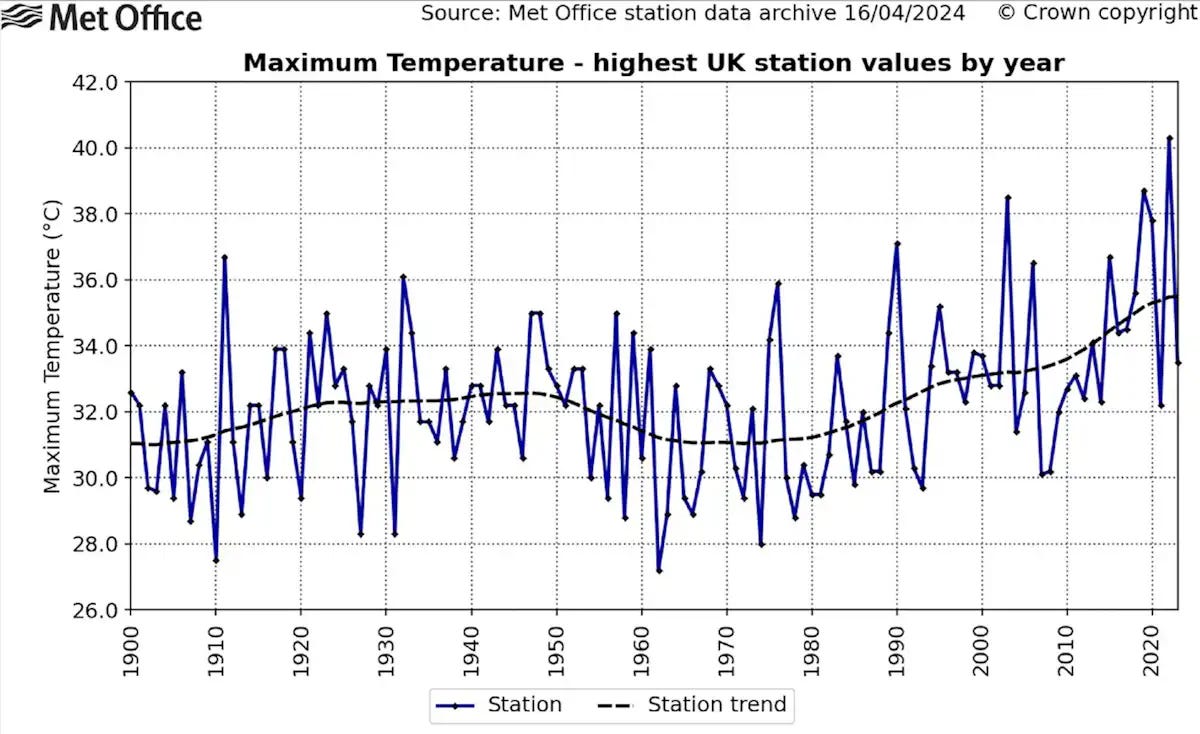

[T]he occurrence of 40°C in the UK in summer 2022, which exceeded the previous UK record maximum set only three years earlier by 1.6°C.

(The UK is getting hotter. Met Office/Kendon et al. 2024/ via The Conversation)

One way to address this is by modelling changes, and as it happened, the possibility of that 40°C temperature in the UK was noticed in models before it happened outside. Scientists run ‘ensembles’ of models that vary slightly the combinations of weather patterns to see what the extremes look like.

One of the models suggested that under certain circumstances Britain could experience multiple days of 40°C temperatures, which could cause series issues for public health. It hasn’t happened—yet. But the fact that it appears in the models suggests that we should take the possibility seriously.

As it happened, I read this within a couple of days of a piece by the climate activist Bill McKibben, where he described the effects of repeated serious weather events on local farmers in Vermont, where he lives.

He called this “abbreviated return time”.

The phrase comes from a report written in the 1990s by the Harvard School of Public Health for the reinsurance company Swiss Re on the long run effects of climate change.

In effect, parts of developed countries would experience developing nations conditions for prolonged periods as a result of natural catastrophes and increasing vulnerability due to the abbreviated return times of extreme events.

He notes that although Hurricane Beryl was fairly weak, as hurricanes go, but it followed within only a few months of a major storm in May that the city hadn’t yet recovered from.

In Vermont, the aftermath of Beryl was a massive rainstorm, but again farmers were still recovering from the previous severe weather events.

Zach Mangione, owner of Cross Farm in Barnet, watched this week’s storm warily as it approached Vermont but thought he would be able to manage an expected 2 to 4 inches of rain.

A friend, who was pumping water from his own basement Wednesday night, prompted Mangione to look outside. At 9 p.m., he saw a river streaming into his barn, where he was keeping 500 week-old chicks.

He got on his tractor and tried to “move dirt and earth to reroute the water towards the brook,” he said. It was “just too late.” He lost 400 chicks.

After that, the storm kept Mangione up all night. He watched in disbelief as the smallest of three streams on his property caused so much damage that he’s now questioning whether he can continue farming the same land — or at all.

There are psychological effects as well. Vermont’s Commissioner of Mental Health, Emily Hawes, has warned that repeat flooding events could “be re-traumatizing”.

There are also financial consequences. In a small state, it becomes too expensive to keep on repairing things. This is made worse because the scale of the damage from extreme weather is larger.

Communities tend to come together in the face of disaster, Rebecca Solnit has described. But I am wondering what the political effects of these social and emotional shocks will be.

j2t#593

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.