8 August 2024. Politics | Energy

The new politics of the far right // Redesigning the energy market to reduce fuel poverty. [#594]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The new politics of the far-right

The second of three pieces on the far right English riots. The first part is here.

Coming back from Italy last summer I got talking to an Italian who lived and worked in the UK as we waited for our delayed Easyjet flight. He was the part-owner of a shop I had bought suits in, in the past, and had been in the restaurant business before that, and he talked engagingly about the business dynamics of both.

And then he got on to The Great Replacement Theory. (The far right politician Giorgia Meloni had been elected Prime Minister of Italy the previous summer.)

The Great Replacement Theory is a racialised conspiracy theory dating back a century that believes

that leftist and Jewish elites are engineering the ethnic and cultural replacement of white populations with non-white immigrants that will lead to a "white genocide."

On Twitter/X, the British journalist Paul Mason posted a summary of the views that sit behind this worldview. In brief: Migration is a form of invasion or occupation, instigated by ‘cultural Marxists’; feminists and liberals are collaborators; believers in the theory need to use symbolic violence to prepare for civil war.

It’s also worth noting here that when Elon Musk tweets about Britain heading for a civil war, as he did this week (analysed here by Marc Owen Jones), this is not a general sociological argument. It is a coded message of support to the far right.

People who believe in Great Replacement Theory are also likely to believe that climate change is a hoax, that vaccination is a form of state control, and that ‘15 minute cities’ are designed to limit freedom of movement.

None of this makes much sense, of course1, but the point is that it’s not meant to. As I was researching the politics of the current wave of far-right riots in Britain, the model I came across that had the most explanatory power was in a thread, and then an article published last year, by the academic Alan Finlayson.2

He describes this politics of the far right as ‘Reactionary Digital Politics.’ In the article, he describes it like this:

It brings older forms of political thought together with participatory, shareable and digital means of communication, giving rise to particular forms and styles of argument and expression. [These] are deployed... for waging polemical warfare on socially liberal ideals of communicative deliberation, and which flout propriety for that very reason.

The through line here, from the abstract, is that

it is unified by opposition to any and all forms of politics concerned with claims for equality.

This is politics, in other words, but not as it is recognised by those who do politics for a living. One of the critical differences is that conventional politics is designed to engage. ‘Reactionary Digital Politics’ is designed to disrupt.

I was struck by this reading a piece on the riots by someone who works in political communications, and almost always offers a fresh insight into politics (so I won’t name them)), and noticing their admitted bafflement about what was going on.

(Ann Coulter at the 2004 Republican National Convention. Photo: Kyle Cassidy via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0)

Finlayson traces Reactionary Digital Politics back to the American right-wing pundit and columnist Ann Coulter, in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Coulter portrayed attributes that were regarded as virtues by liberals as vices. Things like “tolerance, pluralism and rationality” were instead portrayed as an “intolerant” and “exclusionary ideology”:

Coulterism adapted counter-revolutionary, anti-liberal politics... to a celebrity media culture itself intensified by radio talk shows, cable news entertainment (and liberal comedy programmes such as Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show).

Bringing this up to date, Finlayson suggests that

[T]he Coulterist performative critique dominates American politics, and versions of it are prominent across Europe: polemicising against liberalism while expanding the term to encompass a range of positions.

That analysis is familiar to anyone who follows right wing politics: that so-called “woke politics” encroaches on all sorts of individual rights (or ‘freedoms’) and extends into a form of biopolitics through regulating food supply, imposing vaccines, and subverting gender ‘norms’. And so on.

The terms and tropes of that analysis have moved from the bottom of the internet and below-the-line comments into mainstream news commentary and the speeches of, for example, British cabinet ministers.

So this strategy is all about using these forms of disruption to change the terms of the discourse, partly by hammering tropes until they stick. These “ideological entrepreneurs” are “engaged in the business of manufacturing criticism not only of this or that form of politics but of modern politics as such.”3

We’ve seen some of this this week, with the invention of the idea of “two tier policing”, claiming that somehow the peaceful policing of the largely peaceful Black Lives Matters demonstrations, in contrast to the tougher policing against urban rioting and arson, was somehow an expression of liberalism.

The mechanisms of this are worth noting. The Metropolitan Police Commissioner Mark Rowley was asked by journalists about “two tier policing”; news outlets had ended up running (sometimes sceptical) stories about it because far right social media figures kept repeating it, and people like Nigel Farage and Elon Musk had amplified it, so it became a media object. Rowley—rightly in my view—declined to give the questioners an answer that would legitimate the idea.

In response to a question from a journalist that said (and note the syntax, which I have checked against the recording):

Are you going to end two-tier policing, sir?

Rowley appeared to take their microphone and drop it on the ground. I’m a former journalist, and I think someone who asks a loaded question like that—with that worldview embedded it it—gets what they deserve, because it is shocking journalism, but of course in the world of Reactionary Digital Politics the handle on the outrage machine just gets cranked another turn. It was Rowley who ended up apologising, not the journalist.

There’s much more here, for example about how the salience of particular issues can change the way that people vote even if their overall views don’t change.

But in the rest of this piece, it is the transmission mechanisms that interest me. The reason that this matters is because research by Vincente Valentim and colleagues suggests that when mainstream politicians repeat these far right or hard right tropes, it creates greater erosion of social or political norms than when they are repeated by hard right or far right politicians.

This makes sense, of course, but one of the reasons for it is that when hard right politicians make these statements they get more aggressive push back from those on the left.

An excellent piece by Daniel Trilling on the LRB blog spelt some of this out:

While far-right activists like Robinson may inflame a situation, the ideological fuel comes from ostensibly more respectable sources. Islamophobic, anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment has been a staple of Britain’s right-wing press for decades, but we are emerging from a period in which a Conservative government made right-wing populism a central part of its platform. The damage done on this front by the Johnson-Truss-Sunak government needs to be recognised. At each inflection point since 2019, the Conservatives and their media cheerleaders chose to double down on the populist rhetoric, painting their opponents as enemies who threatened the integrity of the nation.

I was struck by a tweet from the FT’s Peter Foster that also made this connection between hard right messages and their amplification.

What this says is that mainstream politicians who start parroting language like “legitimate concerns” or talk about rioters as “anti-immigration protestors” are part of a transmission circuit that Reactionary Digital Politics needs to work.

It also seems as if the media is as important as a transmission mechanism, especially in the UK where there is concentration of billionaire-owned right-wing media, notably in the print sector but now also in billionaire funded (and loss making) television outlets such as GB News.

There is research on media as well. A 2023 paper by Diane Bolet and Florian Foos, which takes an international view of broadcast media, finds, maybe unsurprisingly, that media exposure to “extreme right actors” and their views leads to both higher agreement with extreme right statements and beliefs about how broadly spread they are in the population. Critical interviewing reduces this effect but does not reverse it. It may however, adversely affect the extreme right actor’s image.

The implications:

Media platforms, whether traditional mainstream TV channels or alternative internet platforms, can serve as powerful spaces for spreading and normalising extreme right content... In times of growing media exposure of extremist actors and content, journalists who question the accuracy of extreme right beliefs, and media companies that are willing to enforce standards and de-platform individuals who break them, may be able to counter the empirical pattern that this study documents.

This is an academic way of saying that all of those BBC Question Time producers who have given the hard right populist Nigel Farage a platform over the last decade need to take a long hard look at themselves (along with the producers of I’m A Celebrity), because some of this is down to you.

My time as a journalist was mostly during the ‘80s, in the wake of the rise of the National Front in the late 1970s, when careless news writing led to casual racism, and journalists fought for guidelines to drive that out.4

But one of the things that may be happening as a result of the riots is a crack in the mainstream right, that undermines the political transmission circuit. Certainly when Priti Patel was the Conservative Home Secretary there were times when her rhetoric was indistinguishable from that of Nigel Farage. Yet she made an unequivocal criticism this week of Farage over his claims of “two-tier policing”:

There’s a clear difference between effectively blocking streets or roads being closed to burning down libraries, hotels, food banks and attacking places of worship. What we have seen is thuggery, violence, racism.

Farage himself has been doing damage limitation after promoting the false far-right claims that the Southport attacker was an asylum seeker.

Although the rioters have made the most of the possibilities of asymmetric disorder—private communications channels, the circulation of long lists of places to attack, trying to be unpredictable about where the next outbreak of disorder will happen—there haven’t actually been many hard right rioters on the streets.5 They’ve showed weakness, rather than strength. They may have overplayed their hand.

2: Redesigning the energy market to reduce fuel poverty

I try not to cover pieces here in mainstream newspapers, but there was a piece in the Guardian last week by the paper’s energy correspondent Matthew Taylor that seemed to be a genuinely innovative approach to energy poverty.

The idea is a tariff called “the rising block tariff”. Although it is used in quite a large number of countries, notably across Asia, it is barely known in Europe:

The idea is simple: the first block of energy, which is calculated to meet essential needs from heating to cooking and lighting, is either given at a reduced rate or free. The cost a unit then rises in additional blocks, meaning wealthier homes with excessive or non-essential consumption pay more.

According to its advocates, there are policy benefits at both ends. For poorer households, it reduces fuel poverty. For those at the other end of the scale, who use a lot of electricity, they pay more, which may help to reduce consumption (and therefore emissions). These higher rates can help to subsidise the first block.

One way to organise this is to connect the size of the first block to the amount of energy produced from renewables, which are cheaper, which gives everyone a small but measurable benefit from the clean energy transition.

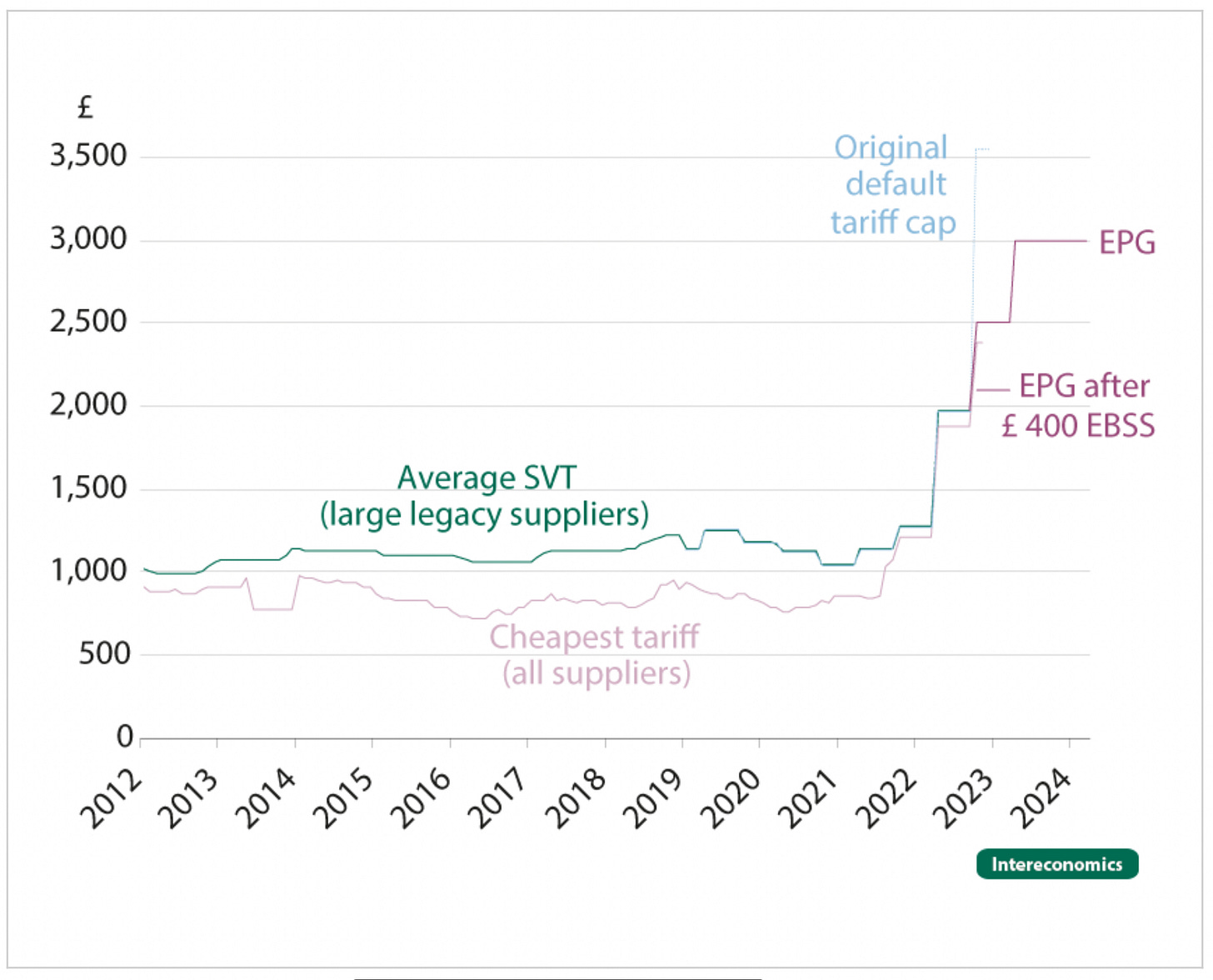

(UK dual fuel bill on a standard direct debit tariff for a typical household. Source: Ofgem; from Bolton and Stewart (2023), via Intereconomcs)

In general the energy system in Europe is in disarray, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the rapid shift away from the use of Russian gas. Governments subsidised energy markets across the continent. The British government spent £20 billion (eventually) underwriting an energy price guarantee [EPG], although that seemed to be poorly designed, since part of the effect was to create windfall profits in the sector that were then subjected to a windfall profits tax.6 Either way, the Cambridge professor Michael Pollitt told Taylor:

We had one of the most expensive energy policies ever implemented. But this cap applied to all consumption which was crazy, because you were subsidising people with swimming pools whereas, actually, we could have done something more sophisticated and targeted and cheaper – which has all these other benefits.

In the UK, the New Economics Foundation has been one of the leading advocated of the scheme, which they call the “National Energy Guarantee”. NEF’s enthusiasm is unsurprising, since they are also a leader in making the case for universal basic services [UBS], where a portfolio of services that are essential for proper participation in society—energy, water, transport, internet—are either subsided or provided free. (More on UBS here on Just Two Things.)

And obviously the block energy tariff is a way of moving towards a UBS model for energy. In some countries a similar pricing model is used for water as well.

In a piece last year, they noted that the UK government had a published rationale for energy support payments:

Current government support for energy bills fails households on four important tests: (i) putting protections around minimum essential energy needs, (ii) providing stability and confidence in future bills, (iii) driving equitable outcomes between social groups, and (iv) speeding up progress against our climate goals.

NEF argued that the block tariff system—especially if linked to progress in clean energy investment—would meet these objectives far more successfully than the energy payments support model rushed in after the energy crisis.

A table in the report they published at the same time points out that under the government’s post-Ukraine Energy Payment System, households in the top decile (10%) by income actually got a bigger share of the EPG payments than the bottom decile.7 The report works through a couple of models, one with two tiers and one with three.

Detail matters in these kind of policy innovations, of course. The Guardian article quotes Jörg Mühlenhoff, the head of the European energy transition programme at the German thinktank the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung:

We need to think carefully about how you define the right quantity of electricity for the lowest block, what is a household, is it based on the number of adults, do you take health vulnerabilities into account – there is a lot still to work out.

Mühlenhoff suggested that the first block needed to be at a fixed price, and that more expensive blocks needed to be more exposed to cost fluctuations, partly to discourage people from using electricity at times of the day when demand was high and it was expensive to produce.

In policy terms, the scheme can be cost neutral. Creating the link between cheaper energy for the first block with renewables has the benefit of creating a public dividend from the clean energy transition. (One of the stories told by populists across Europe is that we are paying more for energy because of the climate transition.)

One of the reasons that this matters, certainly in Britain, is that the current way the electricity market works is profoundly damaging, socially and economically. 4.5 million households, or one in six of the total have to use pre-payment meters as a result of poor payment histories or other issues. The Guardian piece didn’t mention this, but these households—poorer households, almost by definition—end up paying much more per unit of electricity than more affluent custoemrs. The rising block tariff make electricity much more affordable for them—especially if the regulator used the introduction of the system to end this pernicious poverty tax. A recent report by Intereconomics noted that

Current price pressures see increasing “self disconnections” among these households when they do not pay the necessary upfront fees (Citizens Advice, 2023).

This results in their having no energy to heat their houses, or to heat water, or for cooking or for lighting:

This binary choice, made by some of the most vulnerable households, including elderly people, those with young children and people who are susceptible to potentially adverse health consequences, is a particular concern in the cost of living crisis facing British households.

If you’re interested reducing poverty in the UK, you need to address the way energy prices are structured and the way the energy market works. The rising block tariff might be a route to doing this.

j2t#594

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Maintaining a conspiracy on this scale would require more effort, capacity, and competence than the typical state can muster.

I am conscious of the irony of having found a lot of the academic work referenced here in threads over the weekend on Twitter/X, even while the site has been turned into a right-wing cesspit by Elon Musk.

Marc Owen Jones’ analysis of online ‘ideological entrepreneurship’ in the case of the attack on a woman in Brantham, and the manufacture of the hashtag #farrightthugsunite, are both instructive.

Casual racism such as selectively describing suspects in a crime as ‘black’, but not naming their colour when they were white.

The writer Dan Davies said on Twitter/X that any Socialist Worker organiser would be embarrassed to get such small numbers out for a protest.

And were then offered windfall profits tax relief by the government in the following year’s budget.

Looking at other Conservative policies they may have considered this to be a feature rather than a bug, of course.

Excellent writing again. On your 1st topic the Racist and Islamaphobia riots. The RedTories and BlueTories are initially to blame. They spent the whole recent GE and the last 20+yrs scapegoating immigrants and people on benefits for the Cost of living crisis. Then so called journalists and the MSM backed it up.

Your 2nd piece.

The Energy costs are high because Profit is more important. Only way to reduce the costs is to Nationalise all Energy production and supply. Look at Scottish Water, low cost clean repaired quickly and upgraded all the time.