1 March 2025. Ideologies | Addiction

Russell Vought’s White House crusade against American government / Late capitalism is based on addiction [#632]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Tearing down the government

One of the challenges of the current moment is finding a way to get into the mindset of some of Trump’s trusted allies. Because I think we have to assume that they are behaving rationally from within their own worldview, even if it makes no sense from one’s own worldview.

So I have been reading profiles of Russell Vought, the head of the US Office of Management and Budget [OMB]. This doesn’t really have an equivalent in political systems where the President or head of state has less executive power, but its role in the United States’ system is to produce the budget for the President. It also, (from Wikipedia),

examines agency programs, policies, and procedures to see whether they comply with the president's policies and coordinates inter-agency policy initiatives.

So Russell Vought has a lot of influence in the American political system. Here’s an example of a recent memo from Vought, courtesy of Heather Cox Richardson’s excellent daily newsletter, Letters From An American, which is currently required reading for me:

The memo began: “The federal government is costly, inefficient, and deeply in debt. At the same time, it is not producing results for the American public. Instead, tax dollars are being siphoned off to fund unproductive and unnecessary programs that benefit radical interest groups while hurting hardworking American citizens. The American people registered their verdict on the bloated, corrupt federal bureaucracy on November 5, 2024 by voting for President Trump and his promises to sweepingly reform the federal government.”

Well, that’s his worldview right there. In her piece, Cox Richardson critiques some of the claims.

(Project 2025 pin. Photo DonkeyHotey/flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The leftish end of the US political magazine spectrum has been profiling Vought since he arrived in the White House. He was previously at the Center for Renewing America, a Christian nationalist think-tank which he founded, and was one of the main authors of Project 2025, an agenda for Trump if he won.1 Indeed, one of the differences between Trump’s first term and his second term is that this time he took the transition business seriously.

Vought is one of the reasons that Trump spent the first two weeks of his presidency issuing a blizzard of executive orders: he and his team had been at work drafting these since last summer.

A profile in Jacobin is headed ‘Russell Vought Wants to Burn the Government Down’. Democracy Americana headlined its profile, ‘Meet the Ideologue of the “Post-Constitutional” Right’.

Vought has been in politics ever since he left university in 1998. His first job was working for Phil Gramm, a Republican Senator who was an aggressive deficit hawk and an aggressive proponent of deregulation. As Branco Marcetic says in his Jacobin article:

“He said, ‘If you do budget, you do everything,’” Vought later recalled about Gramm. “And so I really took that to the heart.”

His objective is to dismantle the system of American government created by the New Deal. As he says in the Project 2025 handbook:

The goal is to “reduce [the federal government’s] size and scope back to something resembling the original constitutional intent,” aimed at “dismantling” the modern administrative state.

Getting from Phil Gramm’s office at the end of the 20th century to the Office of Management and Budget has involved initially, finding Republican politicians who were as radical as he is and researching and writing their finance and budget proposals, and then joining Heritage Action for America, the lobbying arm of the Heritage Foundation. The Heritage Foundation can be neutrally described as a leading conservative American think tank. He worked for Trump in his first Presidency, becoming head of the OMB in 2019.

And one of the things he has brought along with him from Phil Gramm is using the budget deficit as a way to attack federal spending:

“The most important thing is to go after this deep administrative state, is to defund it,” he said in an interview last year. “This is not about whether we can afford it or not, which we can’t. I would rather burn this money in a parking lot than have it go for the types of things it is going for.”

In his article at Democracy Americana, Thomas Zimmer traces this strand of hardline political rhetoric to the conservative thinker William Buckley in the 1950s. Buckley wrote then:

“It is the job of centralized government (in peacetime) to protect its citizens’ lives, liberty and property. All other activities of government tend to diminish freedom and hamper progress. The growth of government (the dominant social feature of this century) must be fought relentlessly.”

Zimmer’s article is long, and carefully traces the threads in Vought’s belief system. At the heart of this:

Vought is convinced the constitutional order is no more, that the extreme Left has destroyed it, and that truly radical measures are needed to restore it.

A lot of this was set out in an article Vought contributed to The American Mind, the magazine of the Claremont Institute.2 This sounds pleasingly highbrow, but is the part of the American right-wing intellect sphere that has most aggressively promoted Trumpist ideas.

America went wrong, he argues, when

the progressive movement under the leadership of Woodrow Wilson figured out how to “radically pervert” the constitution without having to officially amend it.

The reference to Wilson is a code that invokes the political thinking of Leo Strauss, and his disciple Harry Jaffa. (One of Jaffa’s students founded the Claremont Institute):

West Coast Straussians are obsessed with the Founding – and the idea that America is good because the Framers based the country on certain natural rights and timeless laws of nature, enshrining these eternal laws and morals in the country’s founding documents.

Progressive ideas, therefore, by adjusting to social change, are alienating people—Americans—from these timeless laws of nature:

This, to West Coast Straussians, puts progressivism in the same category as fascism or communism – ideologies that seek to remake man and the world in defiance of the natural order through totalitarian government intervention.

In this worldview, progressives have spent a hundred years capturing the state. Power is now in the hands of the agencies, the bureaucrats, the civil servants. He believes that “the hour is late, and time is of the essence.” The Constitution has already been so subverted that it is, in effect, necessary to ignore the Constitution in order to return to it.

And we saw this in practice when Trump was convicted in Manhattan last year, when Vought took to X/Twitter:

“Do not tell me that we are living under the Constitution. Do not tell me that these are mere political disagreements of Americans with different world views. This is only the most recent example of a post-Constitutional America furthered by a corrupt marxist vanguard pulling out all the stops to protect their own power.”

As Zimmer says, Vought’s language is never about politics: he believes that people who share his views are at war with their political opponents: he talks “about ‘enemy fire’ and ‘battle plans”, of putting civil servants ‘in trauma’. He would have used the Insurrection Act against the Black Lives Matter protestors in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

I should be clear here that I am interested in Vought for what he represents: if it hadn’t been Vought at the OMB it would have been another committed ideologue. But it helps to explain the current disregard in the White House for the conventional understandings of where the President’s power ends and that of Congress starts, and, of course, the attacks on judges who insist on complying with the law.

It’s not clear how Vought became so hardline—he was the youngest child of an electrician and a nurse, both union members. It might be an extreme case of an adolescent rebellion that he’s never grown out of.

Reading this stuff reminds me that it’s easy to think that America is similar to places in Europe, but it’s not. Its particular histories, of slavery and genocide, and some of the mythos associated with both, create some extreme frames.

I spent some time 30 years ago or so teaching film studies to a Masters course at one of Britain’s more minor universities, and one of the classes I had to teach was about the Western, which was a dominant audio visual cultural form in the US for most of the 1950s and 1960s.

At the time structuralist readings of genre—‘paradigmatic accounts’—were popular, in which one deconstructed the genre as a series of opposites. Some of Western’s opposites include:

Gun vs book

Lone hero vs shared community

Personal freedom vs shared responsibility

Tradition vs modernisation

The frontier vs the city

Individual enterprise vs government and rules

White settlers vs native Americans.

Well, you get the picture. But it struck me reading the profiles of Russell Vought that his worldview comes straight out of the mythos of the frontier.

2: The addiction economy

The US academicScott Galloway seems to have watched the Superbowl for the advertisements rather than the game. The ads, he wrote in his No Mercy/No Malice newsletter, were a proxy for what he called “the addiction economy”. The adverts, he said, were a parade for “the food industrial complex, beer and alcohol brands, online gambling, crypto, and social media platforms.”

Pundits claim we live in an “attention economy.” We don’t. Attention is just a metric for addiction. The addiction economy is broader, encompassing media, technology, alcohol, tobacco, gaming, pharma, and health care.

This is about dopa. (He doesn’t define this anywhere in the piece, which is a gap, but I’m guessing he’s using dopa as an abbreviation for dopamine, a chemical that signals desirability in the brain.)

(Ball-and-stick model of the dopamine molecule as found in solution. Via Wikipedia)

He suggests that this isn’t just a feature of modern capitalism, but runs through its history, tracing it back to the sugar and rum that were part of the Triangle Trade, and the East India Company pumped opium into China. Big Tobacco was one of the largest businesses in the 20th century:

Big Tobacco acquired customers with TV ads and endorsements from doctors, but the addictive ingredient, nicotine, is how the industry extracts $86k to $195k per customer — and costs those customers $1 million to $2 million in expenditures, opportunity costs, and health-care expenses.

Galloway argues that around half of the largest companies turn dopa into consumption, across food and beverages, pharma, tobacco and retail: companies such as Coco-Cola, Altria, and Wyeth.

This might constitute investment advice, or maybe a guide to where regulators should turn their attention:

To predict which companies will be the top compounders over the next century, consider this: Eight of the world’s 10 most valuable businesses turn dopa into attention, or make picks and shovels for these dopa merchants.

Part of the article runs through what this means in practice, pretty much sector by sector.

In food for example:

Food companies engineer processed foods, not to maximize nutrition, but to hit the so-called “bliss point” — the exact combination of saltiness, sweetness, and other tastes that makes their product delicious, but not so delicious that consumers feel sated after a small serving. In other words, their food is engineered for more, not nutrition.

20% of Americans are addicted to food, while high consumption of ultra-processed foods increases your mortality rate by 25%. (I wrote about UPFs and their connection to the tobacco sector here recently).

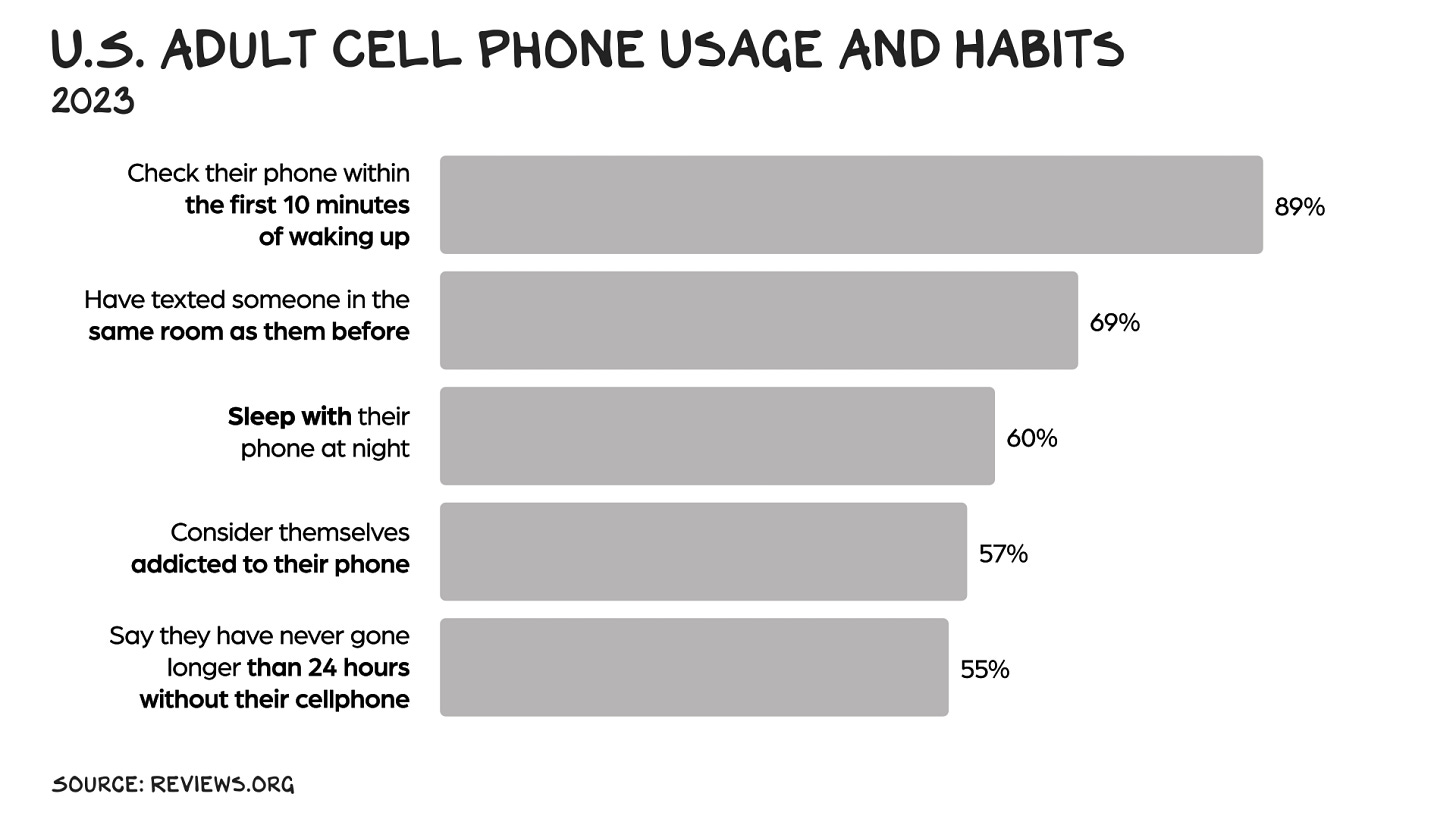

He suggests that while cigarettes are in decline, phones have taken their place as a form of addiction.

Now that everyone has a cellphone, we spend 70% less time with our friends than we did a decade ago. We’re addicted to our phones, and even when we’re not seeking our fix, our phones seek us out — notifying us on average 46 times per day for adults and 237 times per day for teens.

Memorably, he reviews Apple’s deployment of screen tracking and other ‘anti-addiction’ devices as “ a bartender opening an AA chapter”, while Google may not have much of a position in the device market, but the Android OS is like a “gateway drug, as it’s open-source and free.”

And he notes that it took us about 20 years to regulate opiates, and its taken about the same time to start restricting smartphone use, for example in schools.

(Via No Mercy/No Malice)

Galloway quotes his NYU colleague Jonathan Haidt, whose done a lot of work in this area, some of it contested. But it is pretty clear that over-use of social media isn’t good for your mental health (although it may act as an amplifier of existing anxieties.

As my NYU colleague Jonathan Haidt put it, the unconstrained combination of phones and social media has been “the largest uncontrolled experiment humanity has ever performed on its own children.” So far, the results are a mental health crisis: Eight percent of teens are addicted to alcohol or drugs; 24% are addicted to social media.

The article drifts away at the end, but it reminded me of a clip I’d seen of Galloway talking about the second order effects of this. I can’t find it now, but the gist was that while both young men and young women are more lonely than they used to be, they handle it differently. Young women are more likely to be violent to themselves (through anorexia or self harm), while young men are more likely to turn it outwards, into violence.

Talking about social media, phones, and young people, and Big Tech is glamorous and attracts media attention. And these are real problems.

All the same, the intersection of Big Food and Big Pharma, which I wrote about here recently, is probably more damaging to our societies. It produces huge external costs to health and to the planet—perhaps as high as 10% of the global economy. Dopa-based products have unwanted effects for everyone. These are massive market failures.

Other writing: music

(Bessie Smith. Photo: Carl Van Vechten. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)

I wrote a piece about the blues singer Bessie Smith for the Salut! Live folk music blog, where I contribute. It was based on reading Jackie Kay’s updated and reissued book on the singer, part memoir, part biography, part cultural history. I hadn’t realised how big a star she was during the 1920s, when the post-war blues boom struck, or how highly regarded she was by her contemporaries. Here’s an extract:

She was a big woman, in all senses of the word, and a complex personality. The scars of a poverty-ridden childhood never quite left her. She was an alcoholic who was generous with her money but was quick to use her fists to settle disputes.

She was bi-sexual, having affairs with both men and women, especially on the road. Her rough edges never left her. One test for a record company was cancelled when she stopped so that she could spit. But this roughness—channelled into her songs, especially the ones she wrote herself—was one of the things her audiences liked about her.

And here she is duetting with Louis Armstrong. Have a good weekend.

j2t#632

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

In yesterday’s column, Heather Cox Richardson notes that the 23 state Democrat Attorney Generals read the Project 2025 Handbook carefully so they could prepare their legal strategies against it if Trump won.

Reading The American Mind is also instructional when it comes to worldviews.

Exceptional Just Two Things post. Huge thanks! -- D

Thanks for this, its a helpful window into the project 2025 mindset. Unfortunately I think we also need to get into the mindset of Curtis Yarvin / Mencius Moldbug as well, as he seems to be a key influence on what is happening right now... It's so mad it almost functions like an invisibility cloak, but the Guardian gave a good summary of it a few months ago and you can see it underlying the various shocking patterns from corporate asset stripping to de-baathification and mob boss/'caesar' behaviour https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/dec/21/curtis-yarvin-trump

What I couldn't figure out before was how such disparate factions could unite (Project 2025 religioius conservatism and Silicon Valley transhumanist singulatarians(!)) but Yarvin (who is a massive influence on Vance and others ) seems to be their common lodestar, as least as far as tearing it all down goes...

And they do seem to be following his strategy so far. When it comes to building up though, who knows, the inconsistencies seem quite extreme between the different camps, although they do mashup to make a sci-fi dystopia..