20 December 2024. Ultra-processed foods | Risk

Big Food, Big Tobacco, and ultra-processed foods // Roads are the biggest global risk, when you ask people [#623]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Big Food, Big Tobacco, and ultra-processed foods

I hadn’t intended to come back to the subject of food so soon—I had a post lined up on the subject of what might be called ‘anti-climate finance’—but Marion Nestle’s blog (again) signalled a striking development in the world of ultra-processed foods.

A selection of the companies that make them have just been served with a lawsuit in American court. This is the first time that this has happened. The list of defendants is quite something, and certainly worth spelling out in full: Kraft Heinz; Mondelez; Coca Cola; Pepsico; General Mills; Nestle; Mars; Kellogg’s; as well as Post Holdings, Kellanova, and Conagra Brands. Post Holidings is a Philip Morris spin-off; Kellanova is a Kellogg’s spin-off.

Futurists like cases such as this because we see them as a sign that an issue might be moving from the ‘Advancing’ stage of Graham Molitor’s policy S-curve into the choppy waters between ‘Advancing’ and ‘Resolving’.

(‘Advancing’ is that stage in the S-curve where there is general agreement among advocates of change on what the issue is, and why it is an issue, but it’s not that salient to policy makers or government and public institutions. ‘Resolving’ is the area where the issue has the attention of policy-makers, and you start to see regulations and so on start to change as a result.)

The whole UPF issue has been advancing quite fast. Chris Van Tulleken’s high profile book is one example of that. There’s been a wave of advocacy reports getting into details like the public costs of Big Food, another sign that it’s hitting the grey area between Advancing and Resolving. The House of Lords committee report that I mentioned recently is another example of this.

Legal cases are often sighting shots in this process.

The other reason that futurists like cases like this, especially in the United States where law is conducted as a public contest, is that the documents submitted to the court include a lot of data. And so it is in this case. Here the law firm acting for the plaintiff is Morgan & Morgan, America’s largest personal injury law firm, and the document is on their website.

Obviously serious American lawyers don’t get to be that way without knowing how to make a case, and even the Introduction tells quite a story.

Let me pick out a few paragraphs from this. It kicks off by asserting that ultra-processed foods [UPF] are

one of the greatest threats to our health, and the health of our children.

Then it describes ultra-processed foods as being

industrially produced edible substances that are imitations of food. They consist of former foods that have been fractioned into substances, chemically modified, combined with additives, and then reassembled using industrial techniques such as molding, extrusion and pressurization.

Incidentally, if you’re interested in all of this, the whole lawsuit is extensively referenced and sourced.

And then the next paragraphs get onto the (alleged) impact:

UPF are alien to prior human experience. They are inventions of modern industrial technology and contain little to no whole food. However, the prevalence of these foods exploded in the 1980s, and have come to dominate the American food environment and the American diet. The issue is particularly pronounced in children, who now derive over 2/3 of their energy from UPF on average.

The explosion and ensuing rise in UPF in the 1980s was accompanied by an explosion in obesity, diabetes, and other life-changing chronic illnesses.

Some of the consequences are well known—non-communicable diseases associated with ageing started appearing at younger ages in the population. But what’s interesting about the lawsuit is that it tells a business story about why there was an explosion of UPFs in the 1980s. And at the heart of the business story is not Big Food, but Big Tobacco.

This is the result, it says (and you have to keep remembering that an argument is being made here as you read it, even if it is a well-researched argument) of the tobacco companies Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds buying up a stack of food companies in the 1980s.

Collectively, Phillip Morris and RJ Reynolds dominated the US food system for decades. During this time, they used their cigarette playbook to fill our food environment with addictive substances that are aggressively marketed to children and minorities.

UPF formulation strategies were guided by the same tobacco company scientists and the same kind of brain research on sensory perceptions, physiological psychology, and chemical senses that were used to increase the addictiveness of cigarettes.

These two claims are well-sourced as well, including some tantalising footnotes that reference inter-office memos between named scientists in 1990 and 1991.

Big Tobacco companies intentionally designed UPF to hack the physiological structures of our brains.

These formulation strategies were quickly adopted throughout the UPF industry, with the goal of driving consumption, and defendants’ profits, at all costs...

At the same time, Big Tobacco repurposed marketing strategies designed to sell cigarettes to children and minorities, and aggressively marketed UPF to these groups.

The case states that the US food industry now spends about $2 billion marketing UPFs to children; and that “UPFs meet all the scientific criteria that were used to determine that tobacco products are addictive.”

(Down with kids in a Walmart store. Photo: Thayne Tuason, via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

What’s interesting is that the case seems—to me, as a non-lawyer—to turn on a similar claim that has previously caused legal problems for both Big Tobacco and Big Oil: that executives at the food companies knew of the harm that UPFs were doing several decades ago, and chose to ignore it and carry on:

In April 1999, the CEOs of America’s largest UPF companies attended a secret meeting in Minneapolis to discuss the devastating public health consequences of UPF and their conduct.

The plaintiff, Bryce Martinez, has has Type 2 Diabetes and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease since the age 16, and alleges that is the result of his consumption of UPFs.

I’ve just summarised the Introduction here, but if you’re interested in the detail there’s a 98-page section of Statement of Facts that goes into the detail. It includes some pretty questionable examples of advertising to children along the way.

I’d expected to do a quick news search and find at least one public affairs spokesperson for one of these companies declaring the case to be “baseless” and “without merit”, which usually happens in response to anti-corporate lawsuits. Not a peep. The best I could find was a statement from a policy person at the food and beverage industry group Consumer Brands Association blowing smoke (pun not intended but quite pleasing):

“There is currently no agreed upon scientific definition of ultra-processed foods... Attempting to classify foods as unhealthy simply because they are processed, or demonizing food by ignoring its full nutrient content, misleads consumers and exacerbates health disparities.”

I think this is known in the trade as a non-denial denial.

An earlier post by Marion Nestle on UPFs summarised three studies that found that a UPF-heavy diet would lead you to eat around 1,000 calories a day more than if you had a unprocessed food diet.

A couple of notes from me: the first is that an initial case such as this is sometimes an attempt—through the coverage it gets—to bring more plaintiffs into the open, which makes it harder for the defendants to swat the case away, and makes the case easier to fund. And given that Morgan & Morgan is a personal injury lawyer and not a public interest lawyer, we can assume they are fairly sure that there’s potential here for mass tort or a class action suit.

Secondly, having watched my local Sainsbury’s reorganise its shelves recently, it’s increasingly hard to find non-processed foods outside of fruit and veg, some of the bread and cakes, and some of the dairy products. If I were running a supermarket in the current climate, I might be a bit more careful about my category mix.

2: Roads are the biggest global risk, when you ask people

The Lloyd’s Register Foundation runs a World Risk Poll, now in its third edition. The 2024 poll has some interesting findings. It was a serious survey. There are 147,000 respondents in 142 countries. And the report seems to tell us things we don’e always hear in discussions of risks.

The thing that surprised me the most was that across all of the three surveys, risks from ‘road-related accidents’ collisions has been the biggest risk identified. This makes sense—roads are the most dangerous things that we are exposed to everyday—but most polling about risk is not designed to elicit this:

Sixteen percent of the world’s adult population said road-related accidents were the single greatest risk to safety in their daily lives, compared to 13% in 2021 and 16% in 2019.

I’m just going to pause for a moment here to say that there’s a reason why no serious news outlet describes road traffic incidents (or collisions, or crashes) as “accidents” these days, and I’m surprised that a risk report is using the language of accident.

In the headline chart globally, crime and violence comes second overall, and personal health is third.

(Lloyds World Risk Poll 2023)

Climate change and related (weather) risks feature in the top ten, and the executive summary says that this has changed in complex ways in the most recent research when compared to the earlier research:

72% of the world’s adult population now say they feel ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ threatened by climate change in the next 20 years.

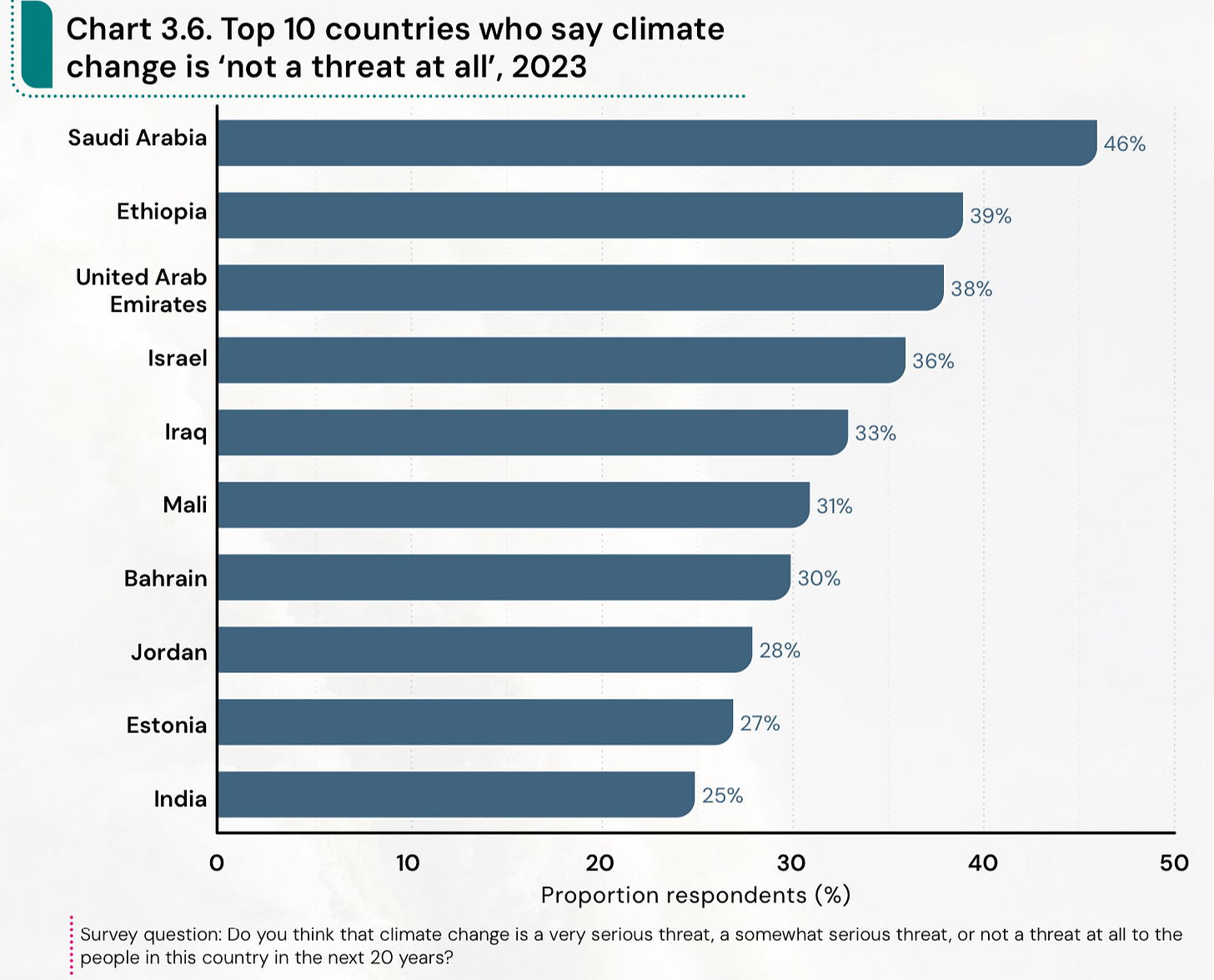

In addition, more people express an opinion on climate change, but this is partly an effect of polarisation—this number includes people who think that climate change is not a threat.

Part of this polarisation seems to be based on the role that fossil fuel businesses play in your national economy (the bigger the role, the higher the level of climate scepticism.)

The reason that roads and traffic come top, I think, is because of the way that the question is phrased:

Now, I have a few questions about risk. By RISK, I mean something that may be dangerous or that could cause harm or the loss of something. Risk could also result in a reward or something good … In your own words, what is the greatest source of RISK TO YOUR SAFETY in your daily life?

In short: the question conjoins ‘risk to your safety’ and ‘in your daily life’, which makes people focus on their own experience and not the kinds of risks they read about online or in media coverage.

All the same, the perception of risk is not exact. People in high income countries are more than twice as likely to as people in low income countries to rate it as a risk, but you are much more likely to be killed or injured on the road in a low income country.

All the same, this is a rationale response to the question, since according to the World Health Organization,

road injuries were the 14th top cause of death around the world in 2021 (accounting for 1.7% of all deaths), but by far the leading cause of preventable deaths.

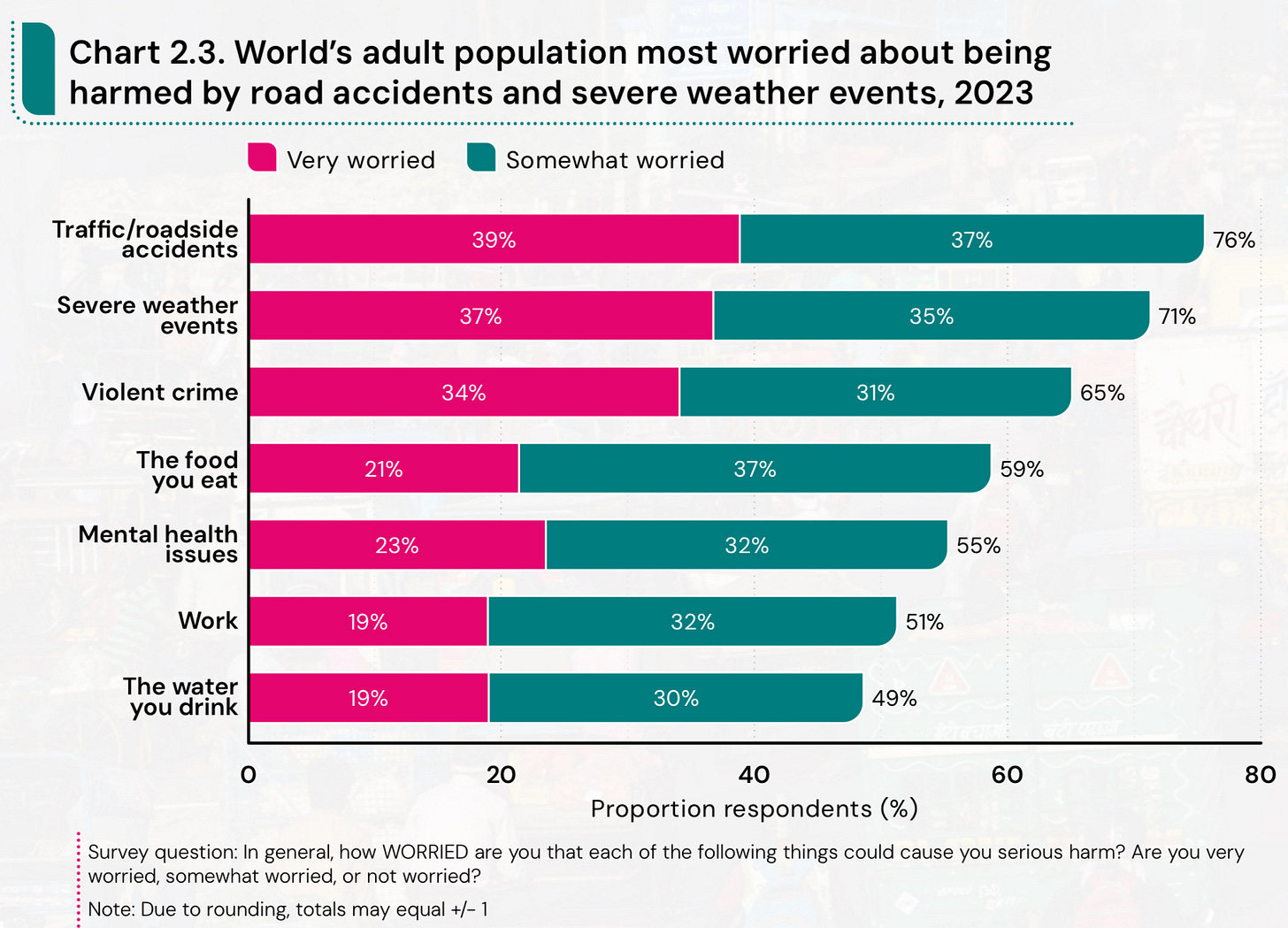

If you rank people’s concerns by their response to the overall list, rather than just their top concern, weather-related events, and by extension, climate change, climb up the list. Here’s the chart:

(Lloyds World Risk Poll 2023)

The top three risks here were the same in 2021.

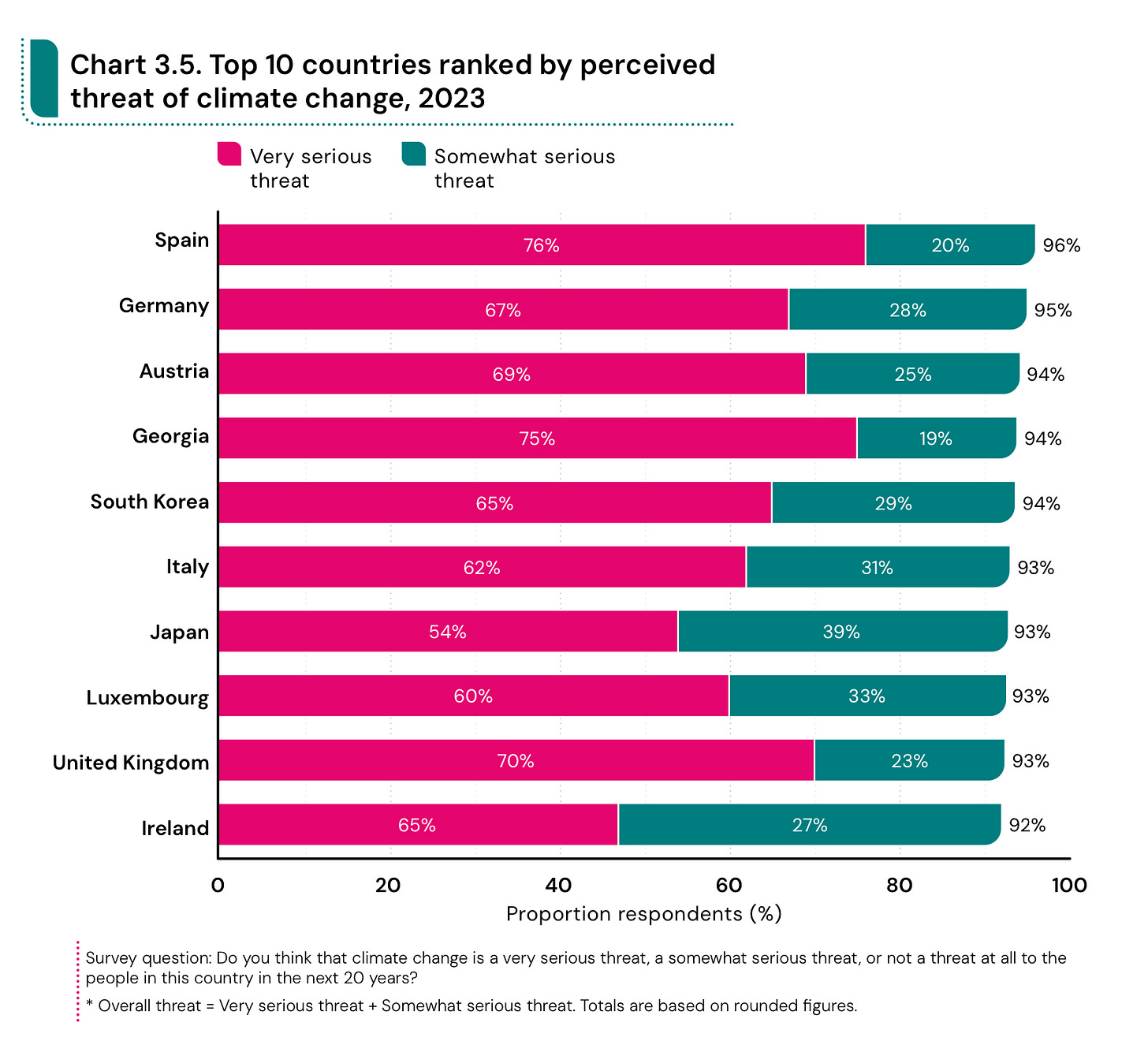

There’s some quite complicated analysis of concern about climate change, and I’m going to share two charts that show both the top ten countries that are most concerned, and the ten that have the highest shares for people who say that climate is ‘not a threat’.

(Lloyds World Risk Poll 2023)

(Lloyds World Risk Poll 2023)

The first set seem to reflect a combination of income levels and an increased experience of disastrous weather events (the underlying data says that experience of flooding is a significant factor). Looking at the list, public policy may also be a factor.

The researchers did some analysis of the factors that are most closely related to feeling threatened by climate change:

[C]oncern about harm from severe weather events has by far the strongest connection to people saying climate change is a very serious threat. Controlling for other factors, the odds that someone believes climate change is a very serious threat are 3.6 times greater when they are very worried about being harmed by severe weather events than the odds when they are not worried about severe weather events.

There’s a similar relationship for people who are “somewhat worried” about severe weather, but it is only half as powerful.

There’s also a positive correlation between final education level and concern about climate change.

Finally, the researchers did an analysis of trends across the various risk categories over the three surveys. What this mostly shows is that there are small variations up and down in each category, which is what you tend to expect when you look at social research. The one exception here in mental health, which shows an upward trend.

It was 45% in 2019, 52% in 2021, and 55% in 2023. (Covid-19 might have amplified the 2021 figure).

Other writing: Music

Over at Salut! Live, the modest folk music site I contribute to, we’ve been running a series called ‘12 Days of Winter’. We’re about half way through, with the last one appearing on Christmas Eve. The emphasis is definitely on seasonal songs rather than Christmas songs, although there are some Christmas songs. Here’s an extract from my introduction:

It’s easy to be dismissive of Christmas songs, and with good reason. These days the popular repertoire includes too much schlock, too much schmaltz, far too much over-sentimental dreck, and not much schmerz…. But the source of many of our seasonal songs is in folk music and collective singing, in the shared experience of the winter holiday, in the traditions of wassailing and carol singing.

The full set of songs, so far, can be found here. And here is Nic Jones’ song Little Pot Stove, from his fine album Penguin Eggs, about the engineers who wintered in South Georgia to repair the whaling ships.

j2t#623

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The best advice I ever had was: Only ever eat things your grandmother would recognise as food!

Perhaps the most interesting post on Substack today, and the most important. I love the penguin eggs album - nice to see it referenced here.