5 December 2024. Food | Dying

How we spend billions subsidising Big Food // The ageing world and new ways of dying. [#621]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend.

1: How we spend billions subsidising Big Food

We’ve known for a few years now that the food industry generates massive external costs, or externalities, that are borne by the public sector. Effectively we’re all subsidising the behaviours and profits of Big Food, But suddenly there’s a swathe of reports in the UK that put some numbers on both the financial costs of this and the politics of it.

Before I get to that, a committee of the UK Parliament’s second chamber, the House of Lords, has also released a critical report about the food sector recently, and I’ll start with that. The committee is the Food, Diet and Obesity Committee, and just to be clear where they were coming from, the report is called:

Recipe for health: a plan to fix our broken food system

The American food campaigner Marion Nestle summarised it this way on her Food Politics blog:

Key finding: Obesity and diet-related disease are public health emergencies costing society billions in healthcare costs and lost productivity.

Key recommendation: The Government should develop a comprehensive, integrated long-term new strategy to fix our food system, underpinned by a new legislative framework.

It’s a chunky report—140 pages not including the Annexes—so I’m going to skip lightly across it here. All the same it’s worth getting a flavour of the tone from the summary:

Obesity and diet-related disease are a public health emergency. England has one of the highest rates of obesity among high-income nations... Unhealthy diets are the primary driver of obesity and preventable diet-related disease. All income groups fail to meet dietary recommendations. This is not because of a collective loss of willpower. In recent decades, unhealthy, often highly processed foods have become widely accessible, heavily marketed and often cheaper than healthier alternatives. There has been an utter failure to tackle this crisis.

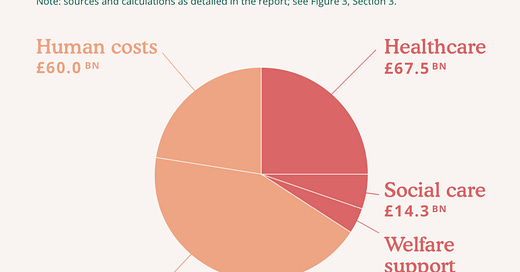

The second report I’m going to mention here sets out to put some costs on the scale of the externalities created by the food sector. The report, for the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission, is called ‘The False Economy of Big Food’. The author is the sustainability economist Tim Jackson. It tells a similar story about the market changes as in the Lords’ quote above, even if its political economy is a bit sharper. But the numbers are staggering.

(Source: The False Economy of Big Food)

So, in summary, if you just look at the direct costs, they represent close to 4% of the British economy. If you include the indirect costs as well, they are more than 10% of the UK economy. (For clarity, these are annual costs: the annual GDP of the UK economy is around £2.5 trillion [£2,500 billion].

By way of comparison, this proportion isn’t out of line with other estimates. The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates the global external costs of the worldwide food market at $10 trillion, against global GDP of $105 trillion.

But this kind of modelling depends crucially on its assumptions, especially when it comes to indirect costs. I’ve looked through the narratives here, and sometimes Jackson is dealing with data that isn’t really collected directly, so has had to build it up from what is available.

This is reasonable enough—people do it all the time. The figures for health costs, social care costs, and welfare costs, and even productivity losses, have been built up carefully from actual data. For example, the report walks through the steps to its assumption that 33% of “chronic disease-related health costs that are attributable to diet.“ The main source is the UK section of the Global Burden of Disease report.

The figure for ‘Human costs’ (£60 million) is trying to quantify “the value of human suffering associated with chronic disease”, and it turns out that there are reasonable estimates of the impact of obesity and overweight in the literature.

Here I think he’s missed out a real cost. One of the effects of poor food on kids is worse educational attainment, leading to worse lifetime outcomes in terms of income and quality of life. Very hard to quantify, but it’s not nothing. And there’s not an imputed figure here for that.

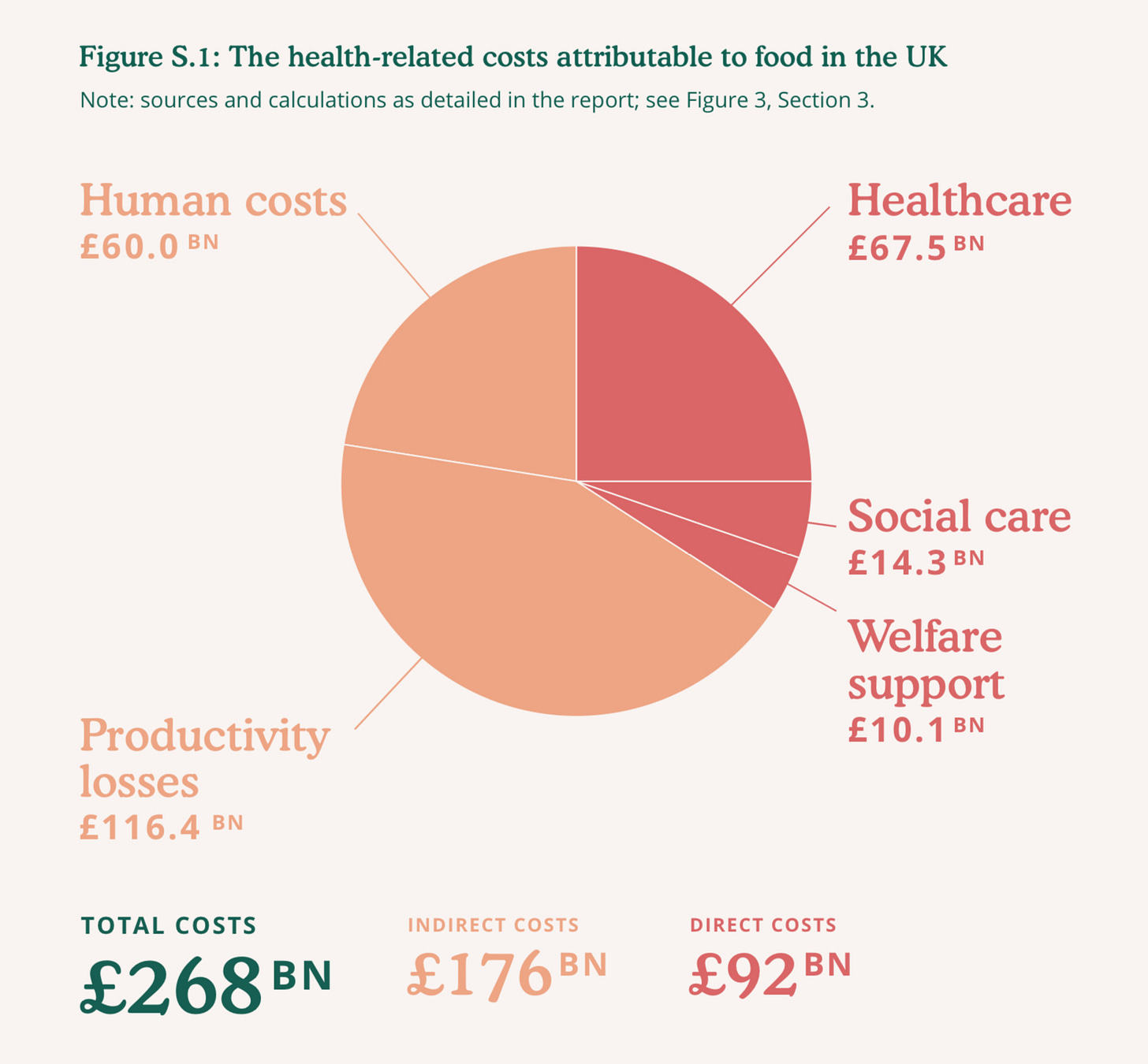

But the real kicker comes when you compare the adverse costs of the current food market with the cost of investing in healthy food.

(Source: The False Economy of Big Food)

The bar chart on the left is the size of the UK annual food spend, plus the direct and indirect costs created by the food market. The bar chart on the right is annual food spend, plus the extra spend that would be needed to create a healthy diet, calculated on the basis of the Eatwell Diet.

Clearly one is a lot smaller than the other. And they are clear that they don’t have specific policy proposals about how to manage the food market to turn ‘bads’ into ‘goods.’ But until you can put an order of magnitude on any of this, policy proposals are going to be ignored anyway.

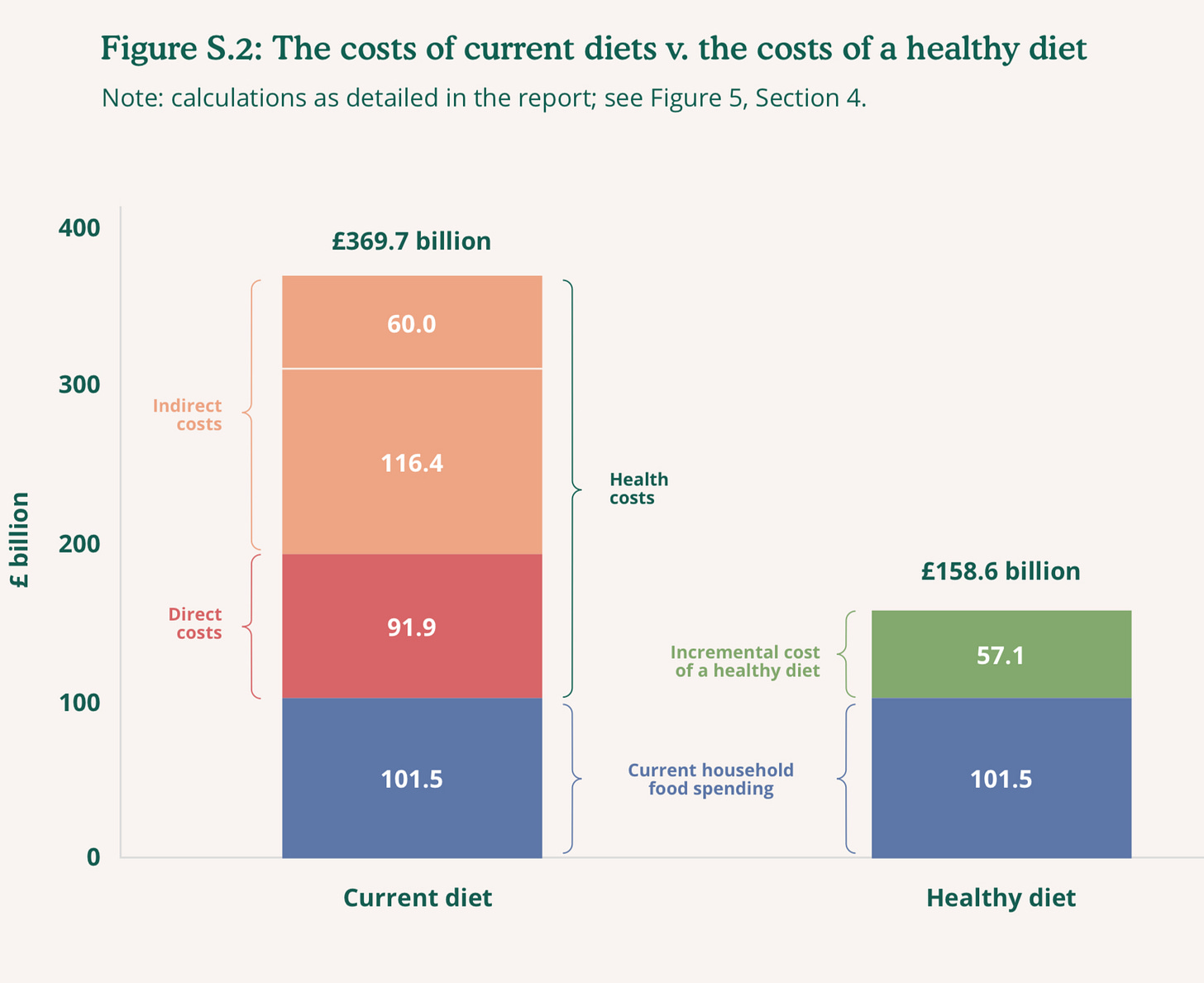

I mentioned a third report, but I’m largely out of space here. It tells the same story of massive market failure that the other reports discuss. But it has a telling clue as to why this continues. I’ll just share one chart from the Food Foundation’s report, ‘The State of the Nation’s Food Industry 2024’.

(Source: State of the Nation’s Food Industry 2024)

The researchers totalled the number of meetings with government departments over three years. It comes to a bit more than 2,400, or 800 meetings a year.

A couple of telling data points: one, over the three years, food industry representatives met with Defra (Department of Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) ministers 1,377 times, and with food NGOs 35 times. Two, more than half of all food industry meetings were with Defra, and around a third with the business department, BEIS. Just 3% of these meetings were with the Department of Health and Social Care.

The Lords’ report has some useful policy proposals (this summarised by Marion Nestle); useful, in that they are good as far as they go.

Exclude businesses making unhealthful products from policy discussions on food, diet and obesity prevention.

Require large food businesses to report on the healthfulness of their products

Tax products high in salt and sugar; use revenues to make healthy food cheaper.

Ban the advertising of less healthy food across all media.

But these are either downstream solutions, or they are trying to nudge the industry towards better behaviour and reduce their influence, a bit.

The False Economy of Big Food heads upstream. It calls for “a new food economy” based on three principles:

the right of every citizen – irrespective of class, income, gender, geography, race or age – to sufficient, affordable, healthy food;

a regulatory environment which curtails the power of Big Food, promotes dietary health and halts the rise of chronic disease;

a financial architecture that redirects money away from perverse subsidies and post-hoc damage limitation, towards preventive healthcare and the production of sustainable, nutritious food.

I was struck by this because the right to sufficient healthy affordable food has come up in a couple of my food projects over the last three years. It’s clearly an idea that’s heading towards the mainstream.

Obviously we’re a long way towards any of this becoming policy, and it will require some skill to get it there. But if it is going to happen, it will be because as societies with ageing populations and burgeoning health costs we simply can’t afford to devote 10% of our economy to indirectly subsidising the food industry.

2: Ageing populations and new ways of dying

A couple of months ago I wrote a couple of pieces here about the globally ageing population. (I’ve since put them together at my blog for ease of reading). They were based on a long article in Foreign Affairs by Nicholas Eberhardt, who documented the dramatic declines in fertility levels across the world. Two thirds of the countries in the world now have fertility rates at below replacement level. South Korea, the outlier, is below one birth per woman.

Your mileage might vary on whether this is a problem, a crisis, or a catastrophe. The underlying problem is that as the population ages, the cost of health and social care increases, and the tax base to pay for this shrinks. The dependency ratio increases, in other words. You can fiddle about with changing the retirement age and so on, but that’s at the edges.

Eberhart thinks this problem is going to become acute, and the numbers certainly support this suggestion. All the same, he still positions it at the “problem” end of the spectrum, and runs through a set of innovation-and-technology solutions that might help out.

I was less sure about his techno-optimism, especially since he seems oblivious to the costs that climate change will also impose on all of these systems at the same time.

Since then, the Financial Times data journalist John Burn-Murdoch has chipped in with a set of charts that underline how vertiginous the fall in fertility levels is: faster and sharper than any of the forecasts.

(Source: Financial Times)1

Here’s examples of that from three countries—South Korea, Colombia, and Chile. The red line shows the actual fertility levels. The blue lines show repeated United Nations projections: all suggesting that fertility levels would fall, but far more slowly.

As Burn-Murdoch notes, referencing work by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde at the University of Pennsylvania:

According to Fernández-Villaverde’s calculations, the combined impact of the yawning misses for emerging market countries and smaller overestimates for wealthy western nations puts the true global population trajectory on the UN’s “low fertility” pathway. That would mean a peak at around 9bn in 2054, 30 years earlier than in the headline forecast.

But the other thing that is happening here is that we’re seeing different patterns of fertility. Previously, declining fertility rates were a problem for high-income problems, especially in East Asia. But now, for example, Mexico’s fertility rate has fallen below that of the United States. As Burn-Murduch notes:

For a while, it was thought that we would see a U-shaped trend: fertility falling with development, then rebounding.

New research suggests that this relationship between development and fertility no longer holds.

Once you’ve written a review of an article, obviously you’re primed.

So you notice the recent story that there is now a robot for every ten workers in South Korea is a small straw in support of the technology view, but seems unlikely to work at scale everywhere.

And you read the post written by Chris Yapp with his wife Gillian Lockwood earlier this year, where they wonder if some medical technologies, such as ‘egg freezing’, might help moderate these effects, although this seems likely to have only a marginal effect.2

But this is probably detail. If future societies might be made destitute by too many older and ill people, it’s possible, even likely, that cultural norms about age and ageing might change.

As ever, art has got here first. In her novel The Children of Men, which is about a sudden loss of fertility in a society, P.D. James imagines a “Quietus”, or state-sanctioned mass drowning of the old off the coast of Suffolk, on the east coast of England.3

We don’t need to go that far. We know that some societies do encourage the old to leave when they run short of resources, even if the story that the old Inuit would take themselves off to the ice—part of a fine lyric by Clive James—seems to have happened only rarely.

What seems to be necessary here is that older people who wish to die can be allowed to die well. In a sense this is what assisted dying about. The current UK Parliamentary Bill on assisted dying (formally: ‘Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill Assisted Dying Bill’) covers only a tiny fraction of such people, but the arguments that is ‘a slippery slope’ are partly driven by this fear: that it represents a legally-sanctioned shift in the way we think about dying.

(For a review of the legal arguments, see David Allen Green’s blog on the subject.)

When I was looking at demographic trends with colleagues at The Henley Centre in the early 2000s, one of my colleagues said simply, “Sooner or later we’ll have assisted dying everywhere”. That’s how I remember it, anyway.

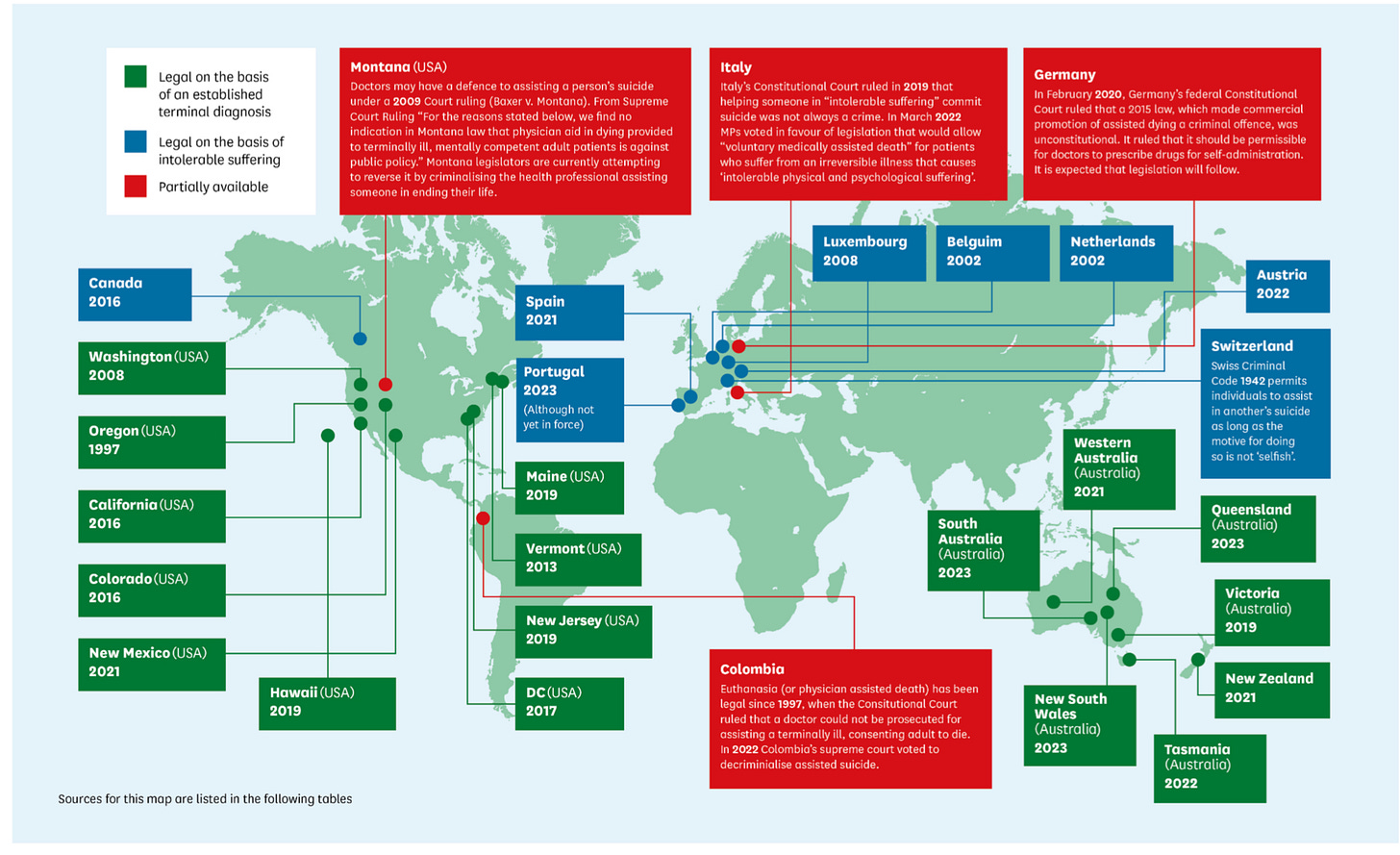

There’s an interesting map on the current law on assisted dying and assisted suicide in different jurisdictions across the world: so far it’s a limited selection. The green tags show jurisdictions where it is legal on the basis of an established terminal diagnosis; the blue tags show those where it is legal on the basis of intolerable suffering; and the red tags jurisdictions where it partially legal.4

(Source: House of Commons Select Committee on Health and Social Care)

All the same, when you look at the policy steps that have taken us to the Bill, whether or not it becomes law, it follows a familiar policy timeline—very similar to Molitor’s policy S-curve.

There is a set of emerging or edge behaviours among some users, in the shape of people travelling to Dignitas in Switzerland, with a grey legal issue as to whether helping people to travel constitutes “assistance”, currently illegal in the UK.

There are significant legal test cases (such as Debbie Purdy in 2009). The Crown Prosecution Service issued a ‘Policy for Prosecutors’ in 2010. There are technical reports from medical organisations on professional ethics and conduct (the General Medical Council in 2013). The British Medical Association issued professional guidance to doctors in 2019.

These are all things that happen as law and behaviours and ethical perspective start to drift apart from each other.

And then it reaches the realm of lawmakers. There’s a private member’s bill in 2015 (these are ‘sighting shots’ that have little chance of becoming law). Assisted Dying Bills are introduced into the House of Lords at different times in the 2010s (again these are forms of parliamentary symbolism, but they show that an issue is live.) There’s a public petition to Parliament in 2022.

In 2024, there’s a report from the Select Committee on Health and Social Care on ‘Assisted Suicide/ Assisted Dying’. (In the UK, one of the roles of the House of Commons Select Committees is to create an evidence base for consideration in areas that might be contested or represent issues where the law is under pressure.) And then you get to a Bill that the Government is willing to give parliamentary time for, while also stating that it will be a free vote for MPs.

That’s how I think this will go. Over time, if societies can’t carry any longer the public or insurance-based costs of health provision in response to morbid symptoms near the end of life, the social norms about expected behaviour at the end of life will change. I imagine we might also see new rituals about dying, and new stories about the nature of what we mean by ‘a good death’. Because that’s the way long term social change happens.

j2t#621

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Note to Financial Times. This is known as ‘fair dealing’ under British copyright law.

In the UK, the average age of a woman at the birth of their first child is now 29. This is, generally, a public health triumph: births to teenage girls are generally social disastrous, for all sorts of reasons. And there are good, rational, economic reasons to delay having children, since it is the point at which women’s earnings fall relative to those of men, as Claudia Goldin’s work has demonstrated.

Apparently P.D. James could see that stretch of sea from the beach hut where she sometimes wrote.

Unsurprisingly the proportion of deaths through assisted dying is higher in countries where it is also permitted as a response to intolerable suffering. Even here, it seems that actual numbers are under-reported.

I have just come back from a holiday in Spain and it was really noticeable the difference in foods and shopping available in the supermarkets. Very little UPF, no ready meals, seasonal fruit and veg, huge fish counters in every supermarket, high quality meat. Huge choice of yoghurt and kefir, very little sweet except flan. I wonder if it’s possible to make comparisons between health in countries like Spain and here? Thank you for the report.

Hi Andrew,

Thank you for your 2 things! I hate newsletters but yours are golden 🌟

Demographic shifts is my thing as a foresight strategist, so I'd like to invite some further thought.

Thanks for highlighting population decline, most people still are unaware and we have a lot of adaptation to do.

In terms of framing, of course it's true this is a complex challenge- but we needn't believe population decline is all bad. What we do need to do, is redesign our economies. Longevity + automation + fewer kids and young people mean the old model of seeing humans as work horses in the production mill - and relying on them to support the pensioners and lesser able - really is out of date. Value in the economy will be created differently, learning and career progression will change dramatically over time, family structures and living look to become more flexible, being older will not mean out of action, and babies could be grown outside of the body in a decade or two. Now it's up to us to start imagining how we want these interconnected drivers and trends to materialise. If we stay stuck in the apocalypse paradigm where a society relies on young worker bodies to function, we get what absolutely nobody wants.

I'm currently working on a collection of scenarios with People Power Foresight - to be published mid 2025, would be happy to share if you like. And to discuss further of course!

Festive wishes ✨️

Isabel