13 January 2025. Obesity | Technology

Understanding the so-called obesity ‘wonder drugs’ // The new Luddites and the enshittification of content. [#626]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Understanding the so-called obesity ‘wonder drugs’.

Over the holiday break Exponential View republished a piece by Azeen Azhar it had run earlier in the year on GLP-1 drugs. (In other words, drugs like Ozempic.) First time around, I’d noticed the headline, but not had time to get into the detail. But seeing it during the holiday meant I was able to give it more consideration.

The Exponential View headline story is this:

I reckon that they will be the most impactful technology in the US over the next two years, with more meaningful and measurable impacts than either artificial intelligence or renewable technologies.

So if that’s right, they’re quite a big deal. The Exponential View piece is behind a paywall (I have a subscription) but Azeem Azhar links to substantive content that is free-to-air that goes into more detail on the mechanics of the drugs.

So, backing up a bit: GLP-1s (more formally, ‘GLP-1 receptor agonists’) were introduced into the market by the large pharma companies initially as a way to help patients with Type 2 Diabetes, but have since become a way to help patients who are overweight to manage their weight down.

Patients, it seems, can’t get enough of them.

GLP-1 prescriptions have quadrupled in the US over the last three years. Recent data shows that nearly 5% of patients receiving any prescription are now prescribed a GLP-1 RA. By some estimates, there were nine million prescriptions for GLP-1s at the end of 2023, which means that 3% of Americans are already on these drugs.

The potential market in American alone is much larger, given that 100 million Americans suffer from obesity.

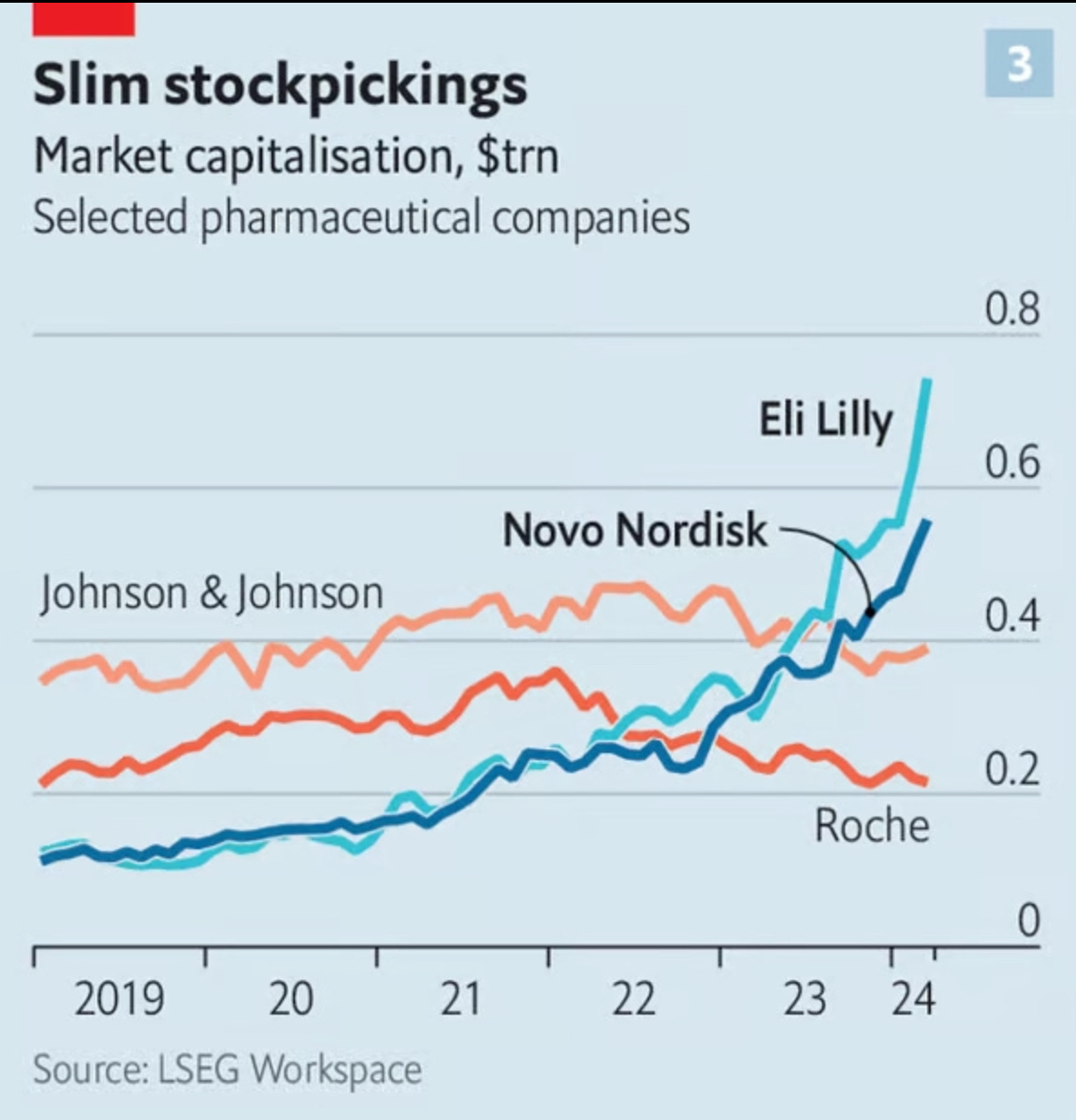

The impact on the pharma companies who make these drugs has been dramatic. Exponential View shared a chart from the Economist that showed the growth in the share price of Eli Lilly, which makes Mounjaro, and Nono Nordisk, which makes Ozempic. Eli Lilly became the most valuable pharmaceutical company in the world in 2023 off the back of its GLP-1 orders, and Novo Nordisk the most valuable company in Europe.

(Source: The Economist/ LSEG Workspace, via Exponential View)

GLP-1s are found naturally in the human body, but are ingested very quickly. What the pharma companies have done is combine it with other chemicals to extend the duration of their effects, as the psychiatrist Scott Alexander notes:

By playing around with its structure, Big Pharma was eventually able to create liraglutide (twelve hours), semaglutide (one week), and cafraglutide (one month).

So we should step back and ask what is going on here. Are GLP-1s a ‘wonder drug’ or a fad? Scott Alexander has looked into this in some detail, and I’ll try to summarise his argument.

He starts by noting the widespread range of things that they seem to be able to treat:

GLP-1 receptor agonist medications like Ozempic are already FDA-approved to treat diabetes and obesity. But an increasing body of research finds they’re also effective against stroke, heart disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, alcoholism, and drug addiction.

Of course, that makes them sound like a wonder drug, rather than a fad. Scott Alexander runs through the reasonably well known explanations of why they work for diabetes, and then points out that the weight loss effects were unexpected. We noticed that they were having that effect before we understood why.

What’s more interesting is that GLP-1s are also associated with reductions in addictive behaviours. Although this is usually reported anecdotally, a more robust meta-study in Brain Science which used a ‘mixed methods’ approach to analyse social media reports about ‘Substance use, compulsive behavior, and libido’ also found this to be the case. From the abstract:

In total, 29.75% of alcohol-related; 22.22% of caffeine-related; and 23.08% of nicotine-related comments clearly stated a cessation of the intake of these substances following the start of GLP-1 RAs prescription... Regarding behavioral addictions, 21.35% of comments reported a compulsive shopping interruption, whilst the sexual drive/libido elements reportedly increased in several users.

As Scott Alexander notes, there is no such a thing as a “miracle drug”. Drugs work by acting on receptors in the body or the brain:

There are two plausible places GLP-1 drugs could lower weight: the body or the brain. In the body, they could change stomach contraction rate, hormone production, etc. In the brain, they could control the mental sensation of hunger. To separate these two effects, scientists bred rats that only had GLP-1 receptors in one place or the other. The results were unequivocal: Ozempic and its relatives work in the brain.

(Ozempic. Photo: Chemist4U/flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

There are reasons why this is surprising, and the mechanisms are definitely complex (read Scott Alexander for all of this), but at a headline level GLP-1s seem to—through different mechanisms—suppress hunger and also influences the (dopamine-based) rewards system in such a way that it suppresses addiction:

Broad-spectrum dampening of the reward system is a terrible fate... But the existence of silver bullet anti-addiction medications—Ozempic isn’t the only one, naltrexone seems to treat a whole host of different drug and behavioral addictions—suggests there’s also a sort of narrow-spectrum dampening, one which affects addictions and nothing else.

Let’s assume, therefore, that these effects are real and that they sustain, and look at the wider implications of this. Exponential View quotes Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley on GDP and labour market participation, which tells you more about the thinness of public policy discussion than anything else.

But they both point to the size of the economic drag of America’s obesity epidemic:

Morgan Stanley reckons the negative macroeconomic impact of obesity is “3.6% of U.S. gross domestic product with a potential $1.24 trillion in indirect costs from lost productivity”.... Goldman Sachs separately reckons the effect of tackling the obesity epidemic through GLP-1 agonists could vary between adding 0.1 to 1.1% to GDP.

Of course, if the effects in reducing addiction are real, then you might see this offset by lower consumption. Walmart say that those using GLP-1 drugs buy less food, and are less likely to eat out or order food for home delivery.

Of course, this isn’t the real effect. The real effect, if they sustain, is about wellbeing: first to improve the physical quality of life of users, so they are able to participate more fully in social and cultural life as well as economic life. And second, in reducing addictive behaviour, it improves the psychological quality of life as well.

Of course, this also comes down to cost. A 30-day supply of Ozempic costs $900 in the US, which is five times as much as in Japan and 10 times as much as in Britain or Australia.

But it’s also worth stepping back and looking at the bigger picture. I have written here recently about both the external costs of the food market—$10 trillion a year globally according to the Food and Agriculture Organization—and the addictive nature of Ultra-Processed Foods.

So this is also a story about late capitalism. Rather than dealing with the causes of the obesity epidemic in the Big Food system, public and private health systems end up paying billions, or more, to Big Pharma, to deal with the consequences.

2: The new Luddites and the enshittification of content

The 19th century British protestors the Luddites get a bad rep, especially among technology enthusiasts. They have become a carelessly applied by-word for people who are against new technologies. But the shortest amount of time spent researching them shows that the technology politics of the Luddites were quite sophisticated, as a recent post at Rob Miller’s Roblog blog points out:

They didn’t challenge the very existence of machines. They didn’t oppose all progress... The Luddites were in fact skilful operators of machinery, and their opposition was not to the machines but to their unfair use, to the capital that was embodied within them, and to the factory owners who wielded that capital against them.

And rather than just saying what they were against, it’s worth spelling out what they were for:

They wanted machines to be operated by workers who had undergone an apprenticeship and who were paid well, and they wanted them to be used to produce high-quality – rather than high-margin – goods... In their own words, they fought against “all machinery hurtful to commonality”.

(Luddites smashing a loom. Photo: Chris Sunde/Wikimedia Commons)

As Dave Karpf said in 2023, in a review of Brian Merchant’s Blood in the Machine:

The Luddites, in other words, were struggling with many of the same questions that we face today. Who should reap the rewards of technological innovations? Whose interests should government represent, promote, and protect? What sort of society do we want to build?

That’s the question that Rob Miller comes back to in his piece, paying particular attention to the way in which media industries have been hollowed out by the streaming services that now dominate content distribution. As he says:

It used to be possible to make a good living as a jobbing musician; in the era of pitiful streaming revenues, AI-generated slop and muzakon Spotify, it no longer is. It used to be possible to make a good living as an ordinary, non-A-list screenwriter or film crew; in the era of collapsing streaming budgets and the elimination of residuals, it no longer is.

And as a journalist friend said to me in an email recently, the role that he used to know as the “editor” is now a “chief content officer”. It all speaks to the same story: cultural production used to exist in something of a balance between production and distribution, but distribution has—with the rise of the web—has become the chokepoint in the economics of cultural markets.

Miller has a short history of 20th century cultural production in his post. Because the Hollywood studios also had control over distribution until the vertical integration of their studios and cinemas was broken up by the American courts.

But the people who made their films also had some power in the system, which was converted into fairer shares—including residual payments for re-use and so on. Perhaps the difference is that the cinema transaction required audiences to make a decision to pay money every time they went to the cinema, and this meant that the studios cared about technical quality—which meant that they also had to care about their technicians.

The combination of subscriptions and the control of distribution means that Spotify and Amazon and Netflix are more concerned about volume, and since people are often doing something else while engaging with the content, or not engaging with it at all, quality doesn’t matter much at all.

(Source: Rosenfeld Media/flickr, CC BY 2.0)

As it happens, there have been a succession of articles in my feeds recently about what this is like in practice. N+1 has a long, long piece about Netflix that I might come back to here, but here’s an extract that relates:

[W]ithholding data protected the company from public scrutiny by obscuring how little audiences were watching its original programming in a meaningful way — from start to finish, or even at all. Netflix was no different from its competitors. “The number of things that tank on Amazon is remarkable,” a former Amazon Studios executive told me. “There are so many things that people hardly watch and it would be embarrassing to release those streaming numbers.”

Amazon, having acquired the Hollywood studio MGM, is in the middle of a stand-off with Bond producer Barbara Broccoli:

One incident reportedly struck a particularly sour note: an Amazon executive referred to Bond as “content,” a term Broccoli viewed as emblematic of a corporate mindset ill-suited to the character.

Meanwhile, a new book about Spotify has made much more visible its practice of ‘Perfect Fit Content’, royalty-free music that is commissioned from production companies according to algorithms which is used to seed playlists and fatten Spotify’s profit margins.

The article’s sub-head is ‘Spotify’s plot against musicians’.

According to a source close to the company, Spotify’s own internal research showed that many users were not coming to the platform to listen to specific artists or albums; they just needed something to serve as a soundtrack for their days, like a study playlist or maybe a dinner soundtrack... As a result, the thinking seemed to be: Why pay full-price royalties if users were only half listening?

Of course, courtesy of Cory Doctorow, there is a term for this: ‘enshittification’:

Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

Unfortunately, the dying part can take quite a long time. All the same, as Rob Miller points out, there’s not the same sort of lock-in on these entertainment platforms as there is for—say—Google or Facebook:

The pipes the content flow down are largely undifferentiated. People’s loyalty is to what they watch, not the service on which they watch it. There isn’t much lock-in here.

The bet the platforms are making is that people don’t care enough when they are consuming content as a secondary activity. But sludge eventually provides a deadweight to these systems—it becomes harder to find things that are worth watching, the music becomes blander and blander, the relentless algorithmic promotion is increasingly irritating.

Rob Miller makes a utopian demand in his piece:

Why can’t we have a sort of guild socialism in the world of media? Why can’t the workers own their work and bring it directly to the public? Why can’t creatives control distribution?

This feels like it is a bit away from where we are now: it probably does need scale. And distribution is a different business from both aggregation and production.1 But utopian demands are also useful, because (as Ruth Levitas reminds us), utopia is the desire for a better way of being or of living.

And as he points out: it’s also worth asking what “commonality” would be like for us in the 21st century.

j2t#626

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

More on this on Just Two Things here.