21 February 2022. Creators | Supply chains

Rebuilding the music sector to reward creators. Supply chain resilience? Just add warehouses.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Rebuilding the creative sector to reward creators

I wrote here last week about Ted Gioia’s analysis that—certainly in the US music market—all the new growth in the market was coming from people listening to ‘old’ music—old defined as more than 18 moths old.

As Gioia says in his Atlantic article, this is a disaster for working musicians. But I think all of this speaks to a bigger problem: that technology platforms have killed an essential part of the media infrastructure.

Since the creative sector is essential to our wellbeing as people (and also has some valuable secondary economic effects), the question of ow do we rebuild a sector that supports that vast majority of musicians, so they can make a living from it, is an important one.

Researching that question takes you pretty quickly to the work of Li Jin, summarised in her HBR article of 2020. She writes about the need for a “creator middle class”. But in practice, what we see is “superstar economics”:

for content platforms, the move to digital content hasn’t been correlated with a burgeoning long tail: the top creators are massively successful, while long-tail creators are barely getting by.

The article has a long list of remedies—10 in all—which I’d judge to be of varying degrees of effectiveness. The three or four that are likely to have the most impact are:

- Increase the level of randomness in the recommendation system (as TikTok does)

- Increase opportunities for collaboration and community between creators

- Create capital investment (and/or grants and/or income) to up and coming creators

- Allow artists to capitalise on ‘superfans’ (see Kevin Kelly, below).

There is some genealogy here. The point about ‘superfans’ comes from the work of Kevin Kelly, who argued that an artist basically needed 1000 ‘true fans’ to make a living.

Both of these models assume that the artist needs to connect directly with their audience. There’s a couple of issues with this: artists get burnt-out; and, despite famous exceptions, it’s hard to gain visibility if you don’t already have it. It also misses an important building block that used to underpin the working of media markets: the aggregator.

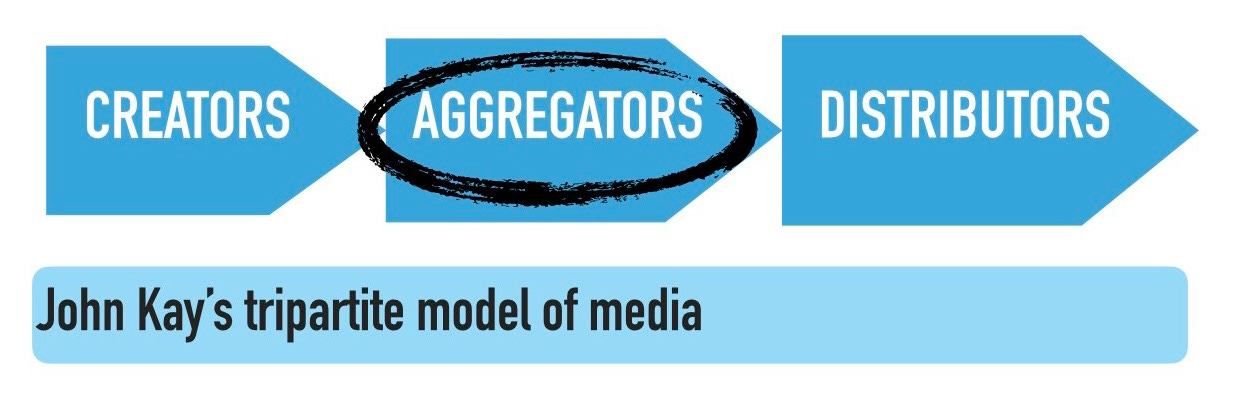

I took this insight from an article that the economist John Kay wrote when he was running an economics consultancy, London Economics, in the 1990s. He observed that media markets had tended to fall into three parts. At one end, there are the creators; then, he said there were aggregators; then there were distributors.

(Source: John Kay)

In the days when we bought music in hard formats, the creators were the musicians: the aggregators, typically, were labels; and the distributors were retailers of different kinds.

Kay’s colleague Andrew Sharp added a layer to this. The risk for creators was low—they could get away with investing little upfront—and the potential rewards high. Retailers, in contrast, had to invest in buildings or leases, but returns were steady (which is why so many of them are now in the clutches of private equity companies). For music companies, historically, risk and reward sat between these two extremes.

What’s happened as a result of the web and its platforms is that the aggregators have been effaced. They are still there, of course, but they’re locked into relationships with platforms such as Spotify that discourage risks. It’s harder for a label such as Creation or Rough Trade to create an identity that builds enough market share.

YouTube merely increases this problem—a flat landscape in which it’s hard to build relationships.

If we’re going to rebuild Li Jin’s creator middle class, then, we need to find some way of reinventing aggregators. That question reminded me of the work of Martin Dale, who was asked by the EU a couple of decades ago about why Hollywood was more successful than the European film industry. Dale’s answer (which doesn’t seem to be online) was that Hollywood had “creative producers” who were able to connect talent, money and audiences, and keep these three in their heads simultaneously.

(Source: Martin Dale, ‘Europa Europa)

Once upon a time this was done by labels—especially specialist labels like Blue Note or Topic or World Circuit. They brought together like-minded musicians and made sure they were able to reach like-minded fans. Specialist distributors like Rounder would aggregate small specialist labels. (The tripartite structure quickly breaks into ecosystems). In the digital world, these need to change.

I’m a fan of British folk music, and one example of a 21st century aggregator is Folk on Foot, which is effectively a small media company with deep relationships in the British folk scene. It is a promoter and a populariser.

By way a case study, it started with the”Folk on Foot” podcast, in which Folk on Foot’s Matthew Bannister—a broadcaster by background—would walk a location with a musician who would talk about it and play some relevant music.

These led to some curation of events and programmes for venues.

When the pandemic hit, he organised some crowdfunded “Front Room Festivals” that channelled some money to the performers and also raised money for a musicians’ hardship fund. Since then—in partnership—they’ve launched a monthly Folk Music Chart Show.

All of this doesn’t necessarily mean that the musicians get paid better, but it creates visibility and also repetition, in terms of reaching fans. And it also means (going back to Ted Gioia) that new music gets heard.

You can imagine an extension to this, where Folk on Foot curates artists who’ve appeared on the Chart Show on Bandcamp, or finds a way to aggregate them on Tidal, or connects to a specialist distributor like Proper Music, driving traffic to a group of artists rather than individuals, and helping listeners and viewers to find them.

Folk on Foot is mostly a media company, supported by fans, with a few other small income streams. Unlike the film industry creative producer, which starts with talent and money and imagines the audience, something like Folk on Foot starts with audience and talent—and should be able to find a way to make the money follow.

There are also more traditional examples. Edition Records has built up stable of jazz groups and performers, and can act as the ‘brand halo’ that encourages listeners to try new things. It was set up by Dave Stapleton, an accomplished performer, and also a fan. (Bannister also started out as a fan).

Some elements of this aren’t new. When Fabric was a successful venue, it curated records by its most popular DJs, for example. The founders of both Atlantic Records and Blue Note were fans before they became music entrepreneurs.

I expect that we’re going to see other examples evolve. But if we’re going to build a “creator middle class”, we also need to see creator intermediaries, driven by fans with an eye for audiences and markets.

2: Supply chain resilience? Just add warehouses.

I’ve probably been talking to clients for a least a decade now about the prospects for re-shoring, or at least near-shoring, production. There’s been some light evidence of this happening, usually where manufacturers needed to be more responsive to changes in consumer demand. The move of some US-owned auto production capacity from Asia to Mexico was an example.

And there was a certain trends logic behind it as well. Worldwide logistics were becoming more complex, and more vulnerable to disruption. Cargo shipping is a particularly dirty form of transport when it comes to emissions, and so on.

But it turns out that when businesses have a real logistics crisis, as in the pandemic, they do the easy things instead. (Of course they do...)

That, at least, is what I conclude from a couple of McKinsey surveys, one from late 2020, one from late 2021, that asked executives how they’d responded to the supply shocks from the pandemic. Read the data from right to left.

Here’s the commentary:

In our 2020 survey, just over three-quarters of respondents told us they planned to improve resilience through physical changes to their supply-chain footprints. By this year, an overwhelming majority (92 percent) said that they had done so. But our survey revealed significant shifts in footprint strategy... In practice (in 2021), companies were much more likely than expected to increase inventories, and much less likely either to diversify supply bases (with raw-material supply being a notable exception) or to implement nearshoring or regionalization strategies.

There are differences between sectors—the more asset heavy you are, the less change you will have made. Chemicals has done the least. But it’s easier and quicker to take a balance sheet hit and acquire some extra warehouse space than it is to do anything that involves restructuring production facilities and logistics systems.

j2t#266

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.