18 February 2022. Music | Google

New music is dying on its feet. The whiteness of tech companies.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: New music is dying on its feet

A couple of readers alerted me to Ted Gioia’s article about the way old music was killing off the new, although it’s taken me a couple of weeks to get to it. Gioia runs a successful music industry newsletter, and there’s little he doesn’t know about the state of the American music industry.

It’s a long piece, so I’ll just try to pull out a few of the most important observations here.

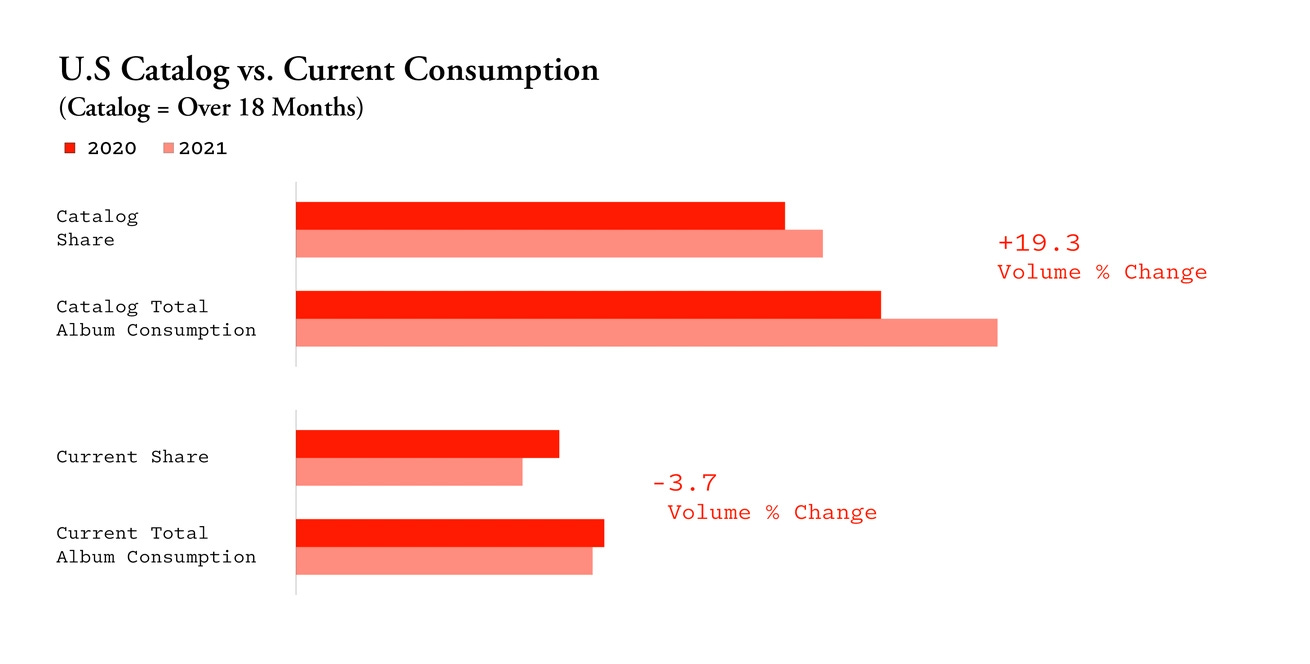

The headline is this: old music now represents 70% of the US music market. It’s worse than that. All the growth in the music market is coming from old music. The market for new music is shrinking, and quite fast. ‘New music’ is recordings that are less than 18 months old:

The 200 most popular new tracks now regularly account for less than 5 percent of total streams. That rate was twice as high just three years ago. The mix of songs actually purchased by consumers is even more tilted toward older music. The current list of most-downloaded tracks on iTunes is filled with the names of bands from the previous century, such as Creedence Clearwater Revival and The Police.

—

(Source: MRC Data via The Atlantic)

He has some anecdote here as well, such as being in a restaurant where the staff were all younger than the music they were playing. But he also suggests that the spectacular collapse in the audience for the US Grammy awards—down to 8.8 million last year, from 40 million in 2012, is a symptom of the same thing. The Grammy awards have been postponed this year, and on those figures one wonders if ‘postponed’ really means ‘cancelled’.

This isn’t good for working musicians, or even for the music industry which, as he says, has a whole business model based on selling new music to listeners:

The entire business model of the music industry is built on promoting new songs. As a music writer, I’m expected to do the same, as are radio stations, retailers, DJs, nightclub owners, editors, playlist curators, and everyone else with skin in the game. Yet all the evidence indicates that few listeners are paying attention.

And pretty much all of the other trends in the industry point in the same direction—notably the increasing perceived value in the catalogues of old music by old artists, which have been selling for large sums to companies such as Hipgnosis and others.

Radio stations are either contributing to this trend, or following the behaviour of their listeners, by putting fewer new tracks into their rotations. And algorithm driven playlists—on streaming services and elsewhere—also encourage conservatism. This has taken its toll on the music industry:

The people running the music industry have lost confidence in new music. They won’t admit it publicly—that would be like the priests of Jupiter and Apollo in ancient Rome admitting that their gods are dead. Even if they know it’s true, their job titles won’t allow such a humble and abject confession. Yet that is exactly what’s happening. The moguls have lost their faith in the redemptive and life-changing power of new music. How sad is that?

Gioia’s not completely despondent about this state of affairs, because he doesn’t think that it’s inevitable. Musicians are still doing interesting things, often mixing up or mashing up genres to create new sounds. The definition of genre pretty much, is that it is “always different, always the same”, but it needs the spark of difference to excite its audience.

I refuse to accept that we are in some grim endgame, witnessing the death throes of new music. And I say that because I know how much people crave something that sounds fresh and exciting and different. If they don’t find it from a major record label or algorithm-driven playlist, they will find it somewhere else... Songs can go viral nowadays without the entertainment industry even noticing until it has already happened. That will be how this story ends: not with the marginalization of new music, but with something radical emerging from an unexpected place.

He has a quick riff towards the end on how Elvis blindsided the music industry in the 1950s, or the Beatles in the 1960s, or hiphop in the 1980s. He could have mentioned punk as well.

I’d like to share his confidence. But I wonder. A lot of big trends are against it. The diffusion of music so it’s everywhere and almost valueless (“like water”, I think David Bowie predicted); the declining importance of place in a world of digital networks; and a softening of generational lines, which means that music has lost that role in creating generational identity. You can add to that list the declining economic power of younger generations. This all may mean that this is just the way that things are going to be now.

2: The whiteness of tech companies

The exodus of anyone who used to work on the ethics of artificial intelligence at Google continues. Alex Hanna, a colleague of Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell, both pushed out of the organisation last year, wrote a very public resignation letter from Google on Medium at the start of this month.

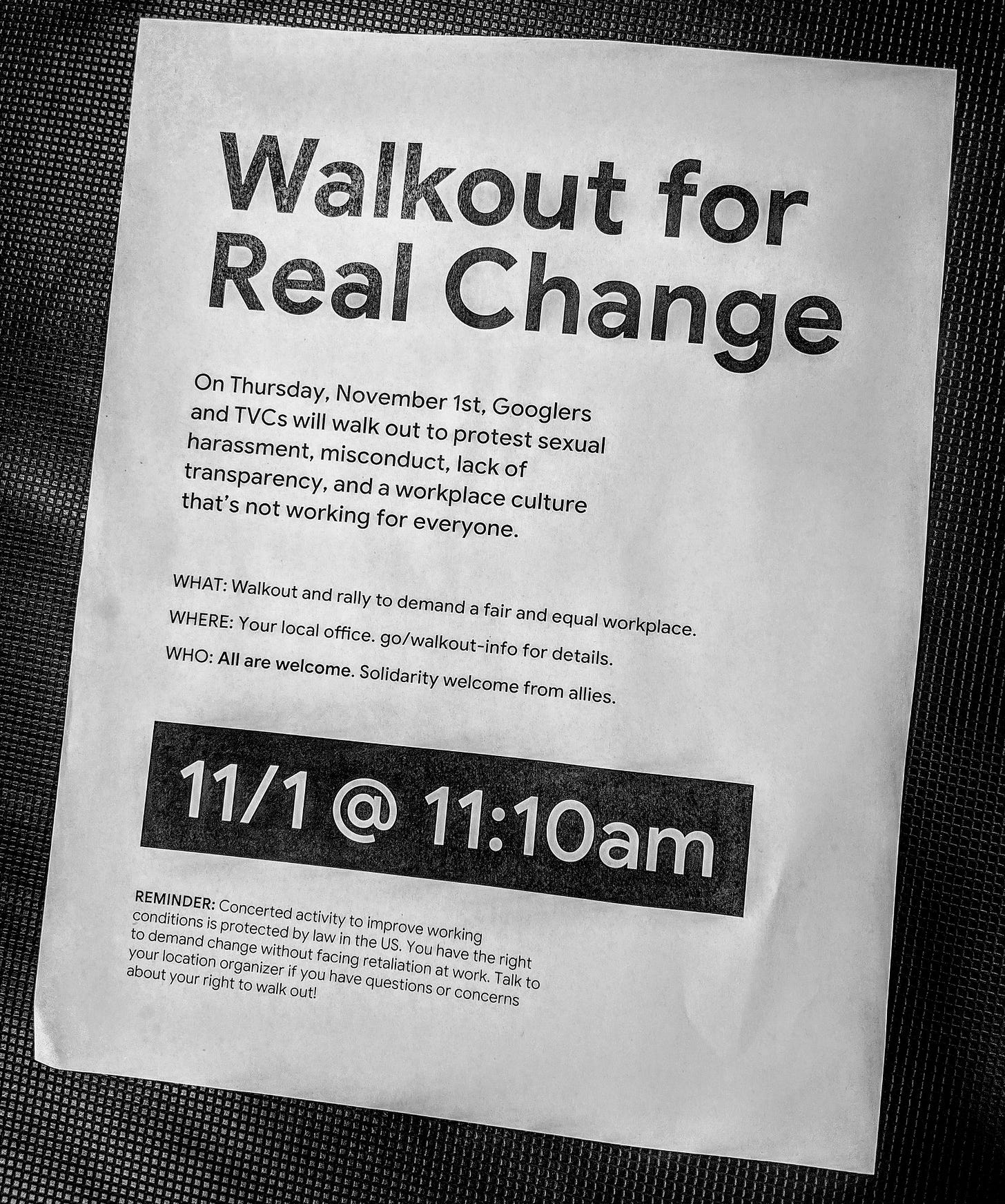

(Walkout for real change, Google, 2018. Photo: Travis Wise/flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Although the first half of the article rehearses some of the things we already know about Google’s hostility to anyone who might be thought of as internally critical, and its failure generally to recruit people of colour to research roles, the second part asks a different question:

I’d rather start working out the ways in which Google, like so many other tech organizations, maintains white supremacy behind the veneer of race-neutrality, both in the workplace and in their products. I also want to think through the methods tech workers can use to challenge and expose their employers’ ongoing investment in white supremacy.

This is strong language of course, but—as I have said here before—you judge a system by what it does rather than what it says, and Google certainly does have a whiteness problem. Like much of Silicon Valley.

Google is not just a tech organization. Google is a white tech organization. Meta is a white tech organization. So are Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and others that are announced in the same breath when we discuss the “techlash”. But so are research centers like OpenAI who are backed by oodles of venture capital from Peter Thiel and Sam Altman, or the Allen Institute for AI, founded by Paul Allen from Microsoft. More specifically, tech organizations are committed to defending whiteness through the “interrelated practices, processes, actions and meanings”, the techniques of reproducing the organization.

Hanna is a sociologist by training, and they bring some sociological method to answering their question. In particular, the use of ‘complaint’, following the work of Sara Ahmed (new to me, but published last year).

By “complaint”, I mean grievances we lodge within our workplaces, which can look both like formal complaints made to human resources (excuse me, I mean “people operations”) and informal complaints which we hold between our peers, comrades, and friends.

Ahmed uses complaints as a lens to look at the way organisations behave. (And I don’t know if this was her insight originally, but what a brilliant insight it is). Hanna quotes her as saying, “The path of a complaint… teaches us something about how institutions work.”

Hanna builds on this:

(C)omplaints can tell us much more about organizational practices, and how those practices reinforce white supremacy. Because of the time we commit to the complaint, we intimately learn the rules that have gone unwritten and the standards that are applied to the letter for marginalized people, but only loosely for white (and upper class/caste Asian) men. Complainers learn the racialized nature of institutions much better than the bureaucrats themselves.

In Google’s case, of course, not just race but also gender.

Hanna also turns the notion of complaint on its head, suggesting that it can also be used as a collective strategy of resistance in the workplace rather than a cry of individual desperation.

(C)omplaint can operate in a positive mode, namely as a strategy of coalitioning and solidarity. It can be a way of acting as a “feminist ear”, as Ahmed calls it: “To become a feminist ear is to indicate you are willing to receive complaints.” It also speaks to the effectiveness of telling stories about tech institutions, as a diagnostic, as an analgesic, and an organizing device.

In their sign-off, Hanna asks researchers to continue the work of looking at tech companies as racialised organisations. And they urge tech workers to continue to complain.

——————————-

j2t#265

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.