11 August 2023. Government | Punk

Michael Lewis’ book The Fifth Risk is about why we have government. // Remembering the man who made punk look the way it did. [#486]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

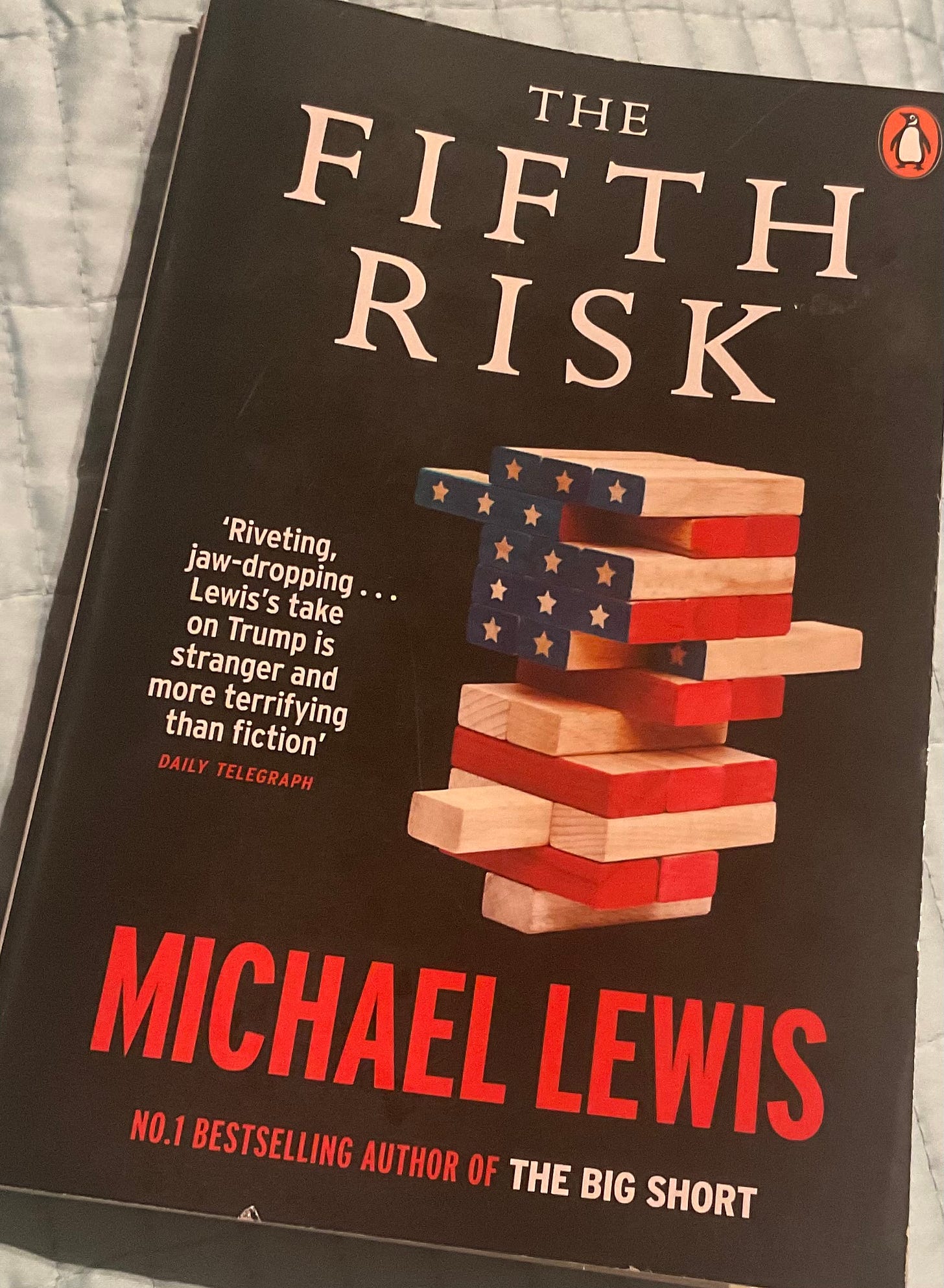

1: Michael Lewis’ book The Fifth Risk is about why we have the public sector.

Michael Lewis’ The Fifth Risk, first published in 2018, is a book about the purpose of government, and the ability of governments and public agencies to make the lives of its citizens better. It seems like a good moment to mention it, for reasons that will become clear, because the book is also about what happens when good government is neglected or undermined.

For The Fifth Risk is a book about the assault on America’s government departments and agencies conducted by the Trump administration when he was President of the United States. This started early, even before Trump had been elected.

(Photo: Andrew Curry, CC NC BY SA 4.0)

The New Jersey governor, Chris Christie, told Trump the summer before the election that he had a legal requirement to set up a Transition team. Trump was uninterested in this, so Christie offered to set it up and run it for him, and even went out to raise money to pay for it; Trump accused Christie of stealing money from him.

(Trump adviser Steve) Bannon and Christie together set out to explain to Trump federal law. Months before the election, the law said, the nominees of the two major parties were expected to prepare to take control of the government. The government supplied them with office space in downtown Washington, DC, along with computers and trash cans and so on, but the campaigns paid their people. To which Trump replied, Fuck the law. I don't give a fuck about the law. I want my fucking money. Bannon and Christie tried to explain that Trump couldn't have both his money and a transition. Shut it down, said Trump. Shut down the transition. (21)

One of the more damaging quirks of the American political system is that although it employs two million civil servants, the top four thousand posts are appointed directly by the President. So a change of government leads to a wholesale change of officials in the top tiers of the Departments.

Hence the need to take Transition seriously. The way this normally works is that each Department prepares a report for the incoming team, and presents it to them. In 2016, the Departments all did this, but no-one showed up. In some cases, new senior officials were not appointed for months.

This is one of Lewis’ ways into the story. He asks his interviewees to tell him what they would have told the Transition team. (Of course, it helps that Michael lewis is one of the best known journalists in America.)

The other way in is through a man called Max Stier, who is the anti-Trump, at least when it comes to American government. Stier’s Partnership for Public Service was designed to attract young people into government, and it was Stier who had persuaded Congress to pass the Transition law that Trump found so tiresome.

He also ran an annual awards event—the Sammies, named for his first funder—for outstanding contributions to public service. Stiers spends a lot of his time explaining to people what the American government spends its time and its money on:

He’d explain that the federal government provided services that the private sector couldn't or wouldn't: medical care for veterans, air traffic control, national highways, food safety guide-lines. He'd explain that the federal government was an engine of opportunity: millions of American children, for instance, would have found it even harder than they did to make the most of their lives without the basic nutrition supplied by the federal government. When all else failed, he'd explain the many places the U.S. government stood between Americans and the things that might kill them." The basic role of government is to keep us safe," he'd say. (25)

The stories that Lewis tells about the cavalier approach of the Trump Administration to all of this are eye-watering. I’m going to try to sketch a couple here.

One of the issues is that the names of America’s government don’t describe what they do very accurately, and if you can’t be bothered to find out, you jump to conclusions.

Half of the Department of Energy’s $30 billion budget goes on nuclear security, for example, at home and abroad. Another $6 million funds the basic science programme that underpins much American innovation. When Trump officials finally showed up in the building, the only thing they wanted to know—shades of McCarthyism—was which staff members had attended meetings of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Six months in to his Administration, Trump nominated as Energy Secretary former Texas Governor Rick Perry, who had once proposed abolishing the Department of Energy.

The Department of Commerce, similarly, has little to do with commerce, “and is actually forbidden by law from engaging in business.” What it does do, though, is collect an awful lot of significant data. It runs the US Census; it looks after the Patent and Trademarks Office; and more than half of its $9 billion budget is spent on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which collects the weather data.

Lewis talks to the data scientist, DJ Patil, who was appointed by Obama as the United States’ first Chief Data Scientist. Obama had signed an executive order the previous year that opened up non-classified government data and required it to be machine readable. Patil had found lots of ways to connect up American data sets to help on public policy issues: it is one of the reasons that the opioid crisis became visible as an epidemic. Some of their police analysis was revealing. For example, police were more likely to use excessive force if they had just come from an emotionally fraught situation.

One of the Trump Administration’s first acts was to remove public data from government websites:

Both the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Interior removed from their websites the links to dimate change data. The USDA removed the inspection reports of businesses accused of animal abuse by the gov-ernment. The new acting head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Mick Mulvaney, said he wanted to end public access to records of consumer complaints against financial institutions. Two weeks after Hurricane Maria, statistics that detailed access to drinking water and electricity in Puerto Rico were deleted from the FEMA website. In a piece for FiveThirtyEight, Clare Malone and Jeff Asher pointed out that the first annual crime report released by the FBI under Trump was missing nearly three-quarters of the data tables from the previous year. (188-189)

There’s a whole section in here on how the Trump Administration almost managed to appoint the head of a secretive commercial weather company to run the NOAA, with the specific intention of preventing the organisation from publishing weather forecasts. It’s a complicated story that takes some explaining, but stinks of insider dealing and corruption.

The people that Lewis meets as he talks to public servants are generally committed to the work they do, and not that bothered about making huge sums of money. Some of them are inspirational. Stier’s Sammy awards celebrate people like Frazer Lockhart, who had organized the first successful clean-up of a nuclear weapons factory, bringing the job in 30 years early and $30 billion under budget.

And Stier noticed a pattern in his award winners:

a surprising number of the people responsible for them were first-generation Americans who had come from places without well-functioning governments. People who had lived without government were more likely to find meaning in it. (24)

Good government is necessary for the public good, and public assets and data are necessary for a public sphere that allows democracy to function and creates accountability. When you look at it like that, it’s not surprising that Trump hates it so much.

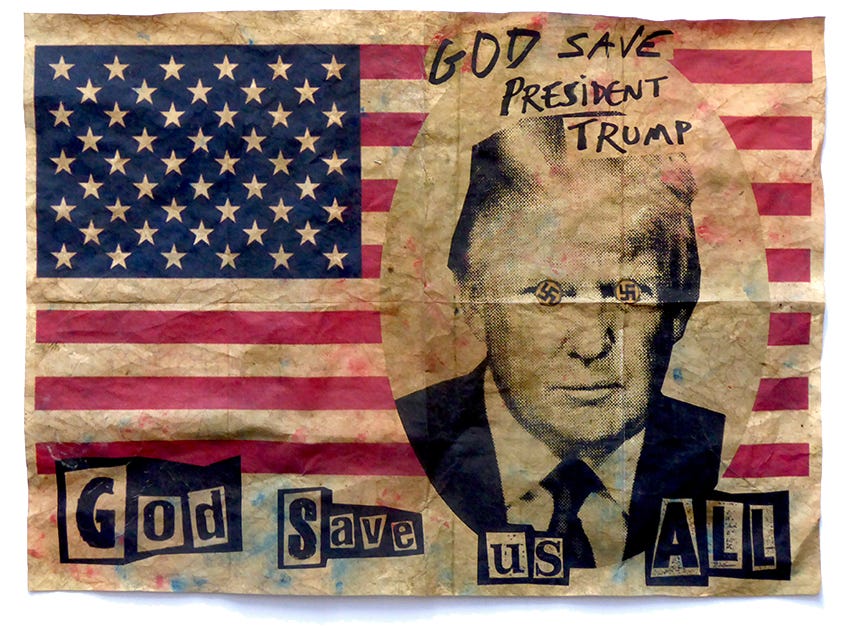

(Jamie Reid, ‘God Save Us All’, 2017. L-13 Gallery)

2: The man who made punk look the way it did

I wanted to remember the artist of punk, Jamie Reid, the man who gave the Sex Pistols’ records their look. Reid has died, and although the impact of some of his images have been dulled by their familiarity, it’s worth remembering their power to shock when they were first seen.

(Jamie Reid. ‘God Save The Queen’, 1977. National Portrait Gallery)

At artnet news, Min Chen has an obituary that captures some of this.

Reid had a bad time at school and had no qualifications, but went to art school in Croydon in south London at a time when you could still do this with no qualifications and get a grant to do it. British art colleges at the time were often a source of radical ideas. While he was there he met Malcolm McLaren, who later created the Sex Pistols while running a fashion boutique in London’s King’s Road.

His graphic design style, however, owed more to his time at a collectively owned community press, Suburban Press, which he helped to set up in the early ‘70s, where speed and immediacy mattered:

“I probably learned more from the printing press than I did in art school,” he said in 1998. “You start developing an appreciation for what actually looks good—out of sheer necessity, from having no money. Some things gain qualities, some things lose qualities. We had to produce things really fast.”

(And the 1998 interview that comes from is interesting throughout, about both the ‘70s and the ‘90s).

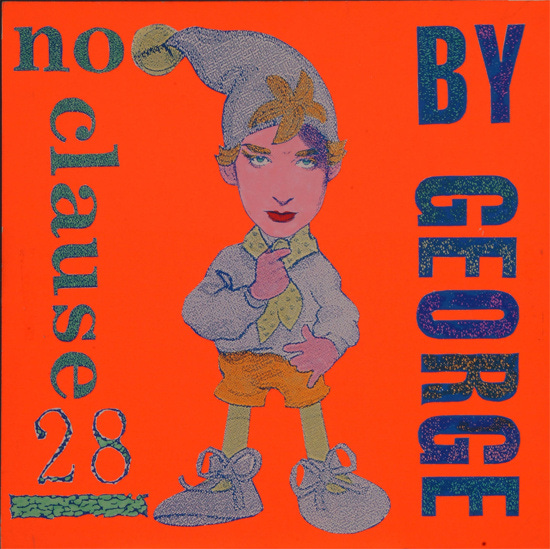

He worked with other bands after the Sex Pistols, but he was also involved in political campaigns, such as the campaign against the Conservatives’ anti-gay Clause 28:

(Jamie Reid, ‘No Clause 28 By George)

In the 2010s, Reid produced an image in support of the Russian group Pussy Riot jailed by Putin—Juxtapoz magazine shared it and reported

that he is encouraging us all to "forward, steal, tweet, print out and paste up, whatever works," in support of Pussy Riot and free speech.

(Jamie Reid, ‘Free Pussy Riot’)

He was also one of a number of artists who created work in support of a young artist who was threatened with legal action by Damien Hirst for copyright violation after using Hirst’s diamond skull in a collage. (This was a bit rich, given Hirst’s own career).

(Jamie Reid, ‘God Save Damien Hirst’)

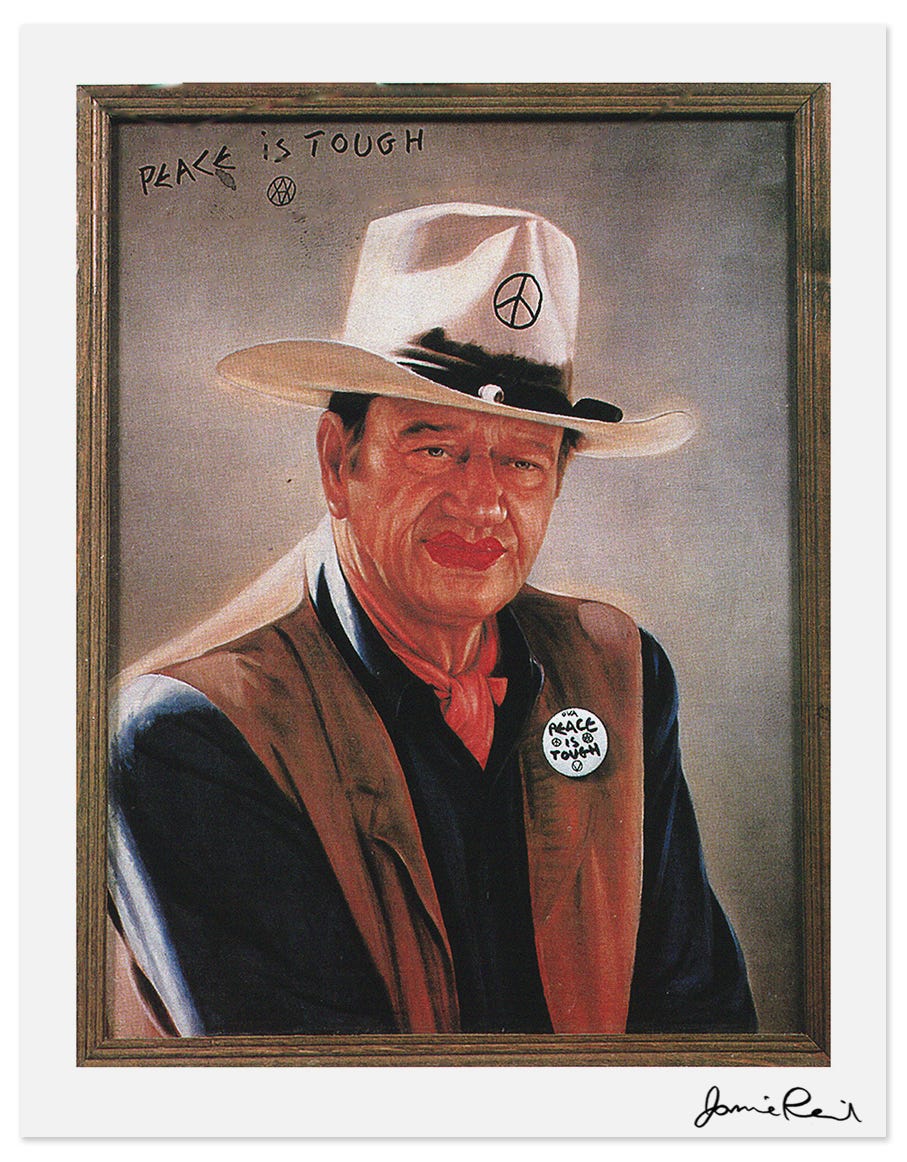

And his knack for political controversy never quite left him. In an interview in Quietus, he talks about the afterlife of his ‘Peace is Tough’ image, which features John Wayne, but not as we normally see him:

A Russian laser artist Alexei Blinov was going to project the image of John Wayne (in Derry) over the river. Then that got banned. And suddenly it was all over the television and front pages. We finished doing that and six months later I got a whole package through the post about an international peace festival, and on the front of it was the 'Peace Is Tough' image. And in a small way, that is so outside the culture of punk and the culture of art galleries and it's wonderful."

(Jamie Reid, ‘Peace is Tough’. L-13 gallery)

Reid had a career retrospective in Hull five years ago, and the artnetarticle points to an entertaining interview he gave at the time of that exhibition, with advice for young artists. The first four are: ‘destroy your computer’; ‘pick up a paintbrush’; ‘have a sense of humour’; and ‘learn from the past’.

The fifth one is ‘Look to the future’, and I’m not just quoting from this because of my priors:

“Radical ideas will always get appropriated by the mainstream. A lot of it is to do with the fact that the establishment and the people in authority actually lack the ability to be creative. They rob everything they can... That’s why you have to keep moving on to new things.”

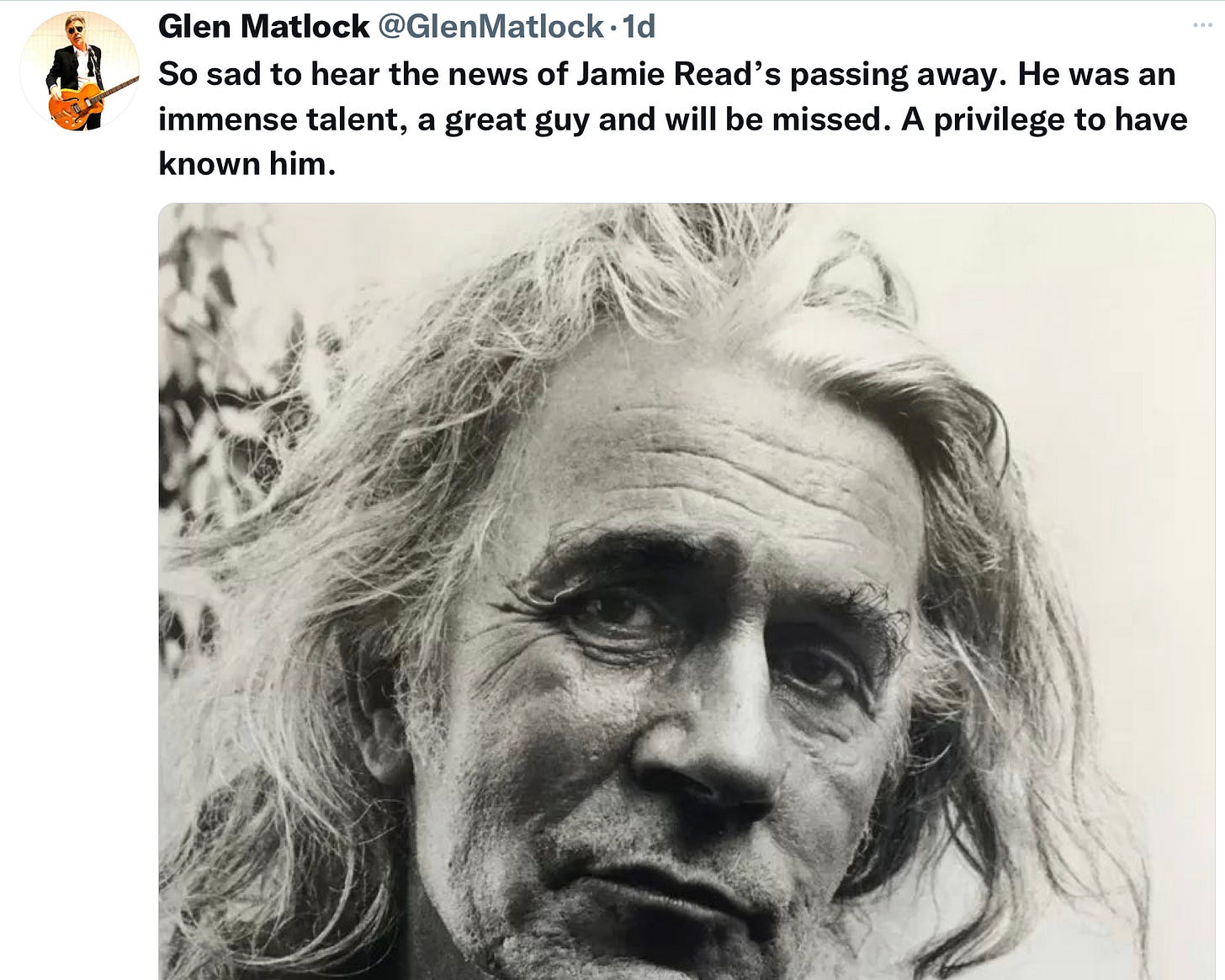

After Reid’s death the chronicler of punk Jon Savage, with whom he had co-written a book, tweeted an appreciation. As did Glen Matlock, the only member of the Sex Pistols to leave the band with their integrity intact. Matlock’s has a recent portrait of Reid that I rather liked.

j2t#486

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.