3 May 2025. Collapse | Apple

The Limits to Growth was right about the coming collapse // Updates: America’s financial risk premium. Norway’s food marketing law. Apple’s bad day in court [J2T #638]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

A slightly different format as a one-off today: one lead article followed by three shorter updates on issues that I have been following on Just Two Things. Have a good weekend.

1: The Limits to Growth was right about the coming collapse.

I’m used to environmentalists and futurists writing about The Limits to Growth. I’m less used to seeing investment writers mention research that’s linked to The Limits of Growth. But that’s what Joachim Klement did in his daily newsletter a couple of weeks ago.

Of course, anyone who writes about Limits of Growth has to do all the usual disclaimers first. This is because the combination of the words “limits” and “growth” in the title produced a lot of critical responses, on a range from straight-up hatchet jobs which misrepresented the book, to people who didn’t appear to understand the systems dynamics model that sat behind it.

(Photo: The Club of Rome)

(I edited a special edition of the APF newsletter Compass that looked back at Limits to Growth. There’s an article in there by Ugo Bardi that goes into the detail of the history of the assault on Limits when it was published.)

Klement puts it this way:

Here is what the model actually predicted. The scientists at the MIT modelled three scenarios [actually 13, including these three–AC]: business as usual (what was then called ‘standard run’), a technologically enhanced world where technological progress eliminates most limits to growth, and a stabilised world where our economies shift to a sustainable (i.e. non-resource consuming) model by the turn of the century.

The trouble with the ‘standard run’ is that its 50-60 year outcomes weren’t that good. They suggest that global industrial output will start to decline in the mid-2020s (checks calendar), and that global population will start to decline in the mid-2030s.

In the 2010s, Graham Turner looked at the standard run against out-turn data, as Klement reminds us, and found it a good fit. Gaya Herrington updated this research in the early 202s—as per my Just Two Things piece linked here—and it was a still a good fit.

Now another group of scientists have gone back to the original World3 model and recalibrated it against the best fit data, which is what has prompted Klement’s article. ‘Recalibration of limits to growth: An update of the World3 model’, by Nebel et al, is published open access in the Journal of Industrial Ecology.

The point of doing this is—as they say in their abstract—is

to better match empirical data on world development.

For assurance, the article goes into detail about their method and their approach, including access to the Python scripts they have used, which have been posted on Github. As they explain:

Since the model was calibrated with the limited capabilities in terms of computing power and data processing in 1972, it seems interesting to what extent a recalibration of the model is possible and what are the effects of such a recalibration. The data situation has improved enormously since then.

What this means is that the recalibrated model reflects the best available current data.

Klement explains the approach this way:

If the recalibrated model deviates significantly from the forecasts of the 1970s, we have made progress. And given the accuracy of the original model, we can also take some comfort that any progress we made is likely to be real and we have truly extended economic growth further into the future.

And the outcomes of this recalibration? Well, they’re not good. Again from the abstract to the article:

This improved parameter set results in a World3 simulation that shows the same overshoot and collapse mode in the coming decade as the original business as usual scenario of the LtG standard run. [My emphasis]

It is worth spelling out the dimensions of this overshoot and collapse. As it happens, there are some handy charts both in Joachim Klement’s article and in the original paper. I’ve reproduced Klement’s versions here because they are easier to read, but the originals are downloadable from the original article.

The first chart is for industrial production, where the recalibrated version tracks the original to the centimetre, pretty much. Does this matter? Klement does the usual wave towards the fact that we live in a much more services-based economy than we did even when the Limits team did the original study.

(Source: Nebel et al, 2023, adapted Klement)

I’m not completely convinced of this. As David Mindell observes in The New Lunar Society (I have a review in the works), industrial production has significant multiplier effects on other economic activity, even if this is largely overlooked by economics [p33]. The updated population diagram also follows closely the decline in the mid-2030s that is seen in the Limits base case projection.

On food production, it

also seems to be peaking right about now indicating that despite continuous growth in the global population, we are experiencing declining global food production.

So it’s possible to imagine that one of the reasons why population starts to decline is because there isn’t enough food to go around. It’s also possible to imagine that the higher peak, and faster overshoot, is a result of the intensification of agriculture and food production, which is about the application of technology. As one of the Limits authors, Dennis Meadows, always insisted when asked, technology can delay a peak, but the crash comes harder when it comes.

(Source: Nebel et al, 2023, adapted Klement)

The third chart here is for ‘persistent pollution’, which is a modelling shorthand for a range of externalities including CO2 emissions. Here, on the face of it, we have beaten the model: ‘persistent pollution’ is currently much lower than the World3 standard run. But given that it climbs much higher, and hangs around for much longer, it actually just seems that with better data it turns out that initial effects were less severe but the delays in the system were much greater than the original model assumed.

(Source: Nebel et al, 2023, adapted Klement)

The last chart assembles something from the data that wasn’t done in the original Limits to Growth work because the concept hadn’t been developed. But it is possible to assemble a Human Development Index from the data, and reference it against the original model and the revised version. It doesn’t come out well.

(Source: Nebel et al, 2023, adapted Klement)

On this last chart, Klement is most depressed, and I think with good reason:

If [this chart] is true, it says that today is peak human civilisation, from now on we are going backward on a global level in terms of human development and quality of life, While some countries will continue to improve, other countries and the planet as a whole will start to go backward, ultimately dropping back to similar levels of human development and quality of life as in 1900 by the end of this century.

The overall conclusion by the article’s authors is:

[T]he model results clearly indicate the imminent end of the exponential growth curve. The excessive consumption of resources by industry and industrial agriculture to feed a growing world population is depleting reserves to the point where the system is no longer sustainable. Pollution lags behind industrial growth and does not peak until the end of the century. Peaks are followed by sharp declines in several characteristics.

They also note that the cause of this turning point is resources, not ‘pollution’:

This interconnected collapse... occurring between 2024 and 2030 is caused by resource depletion, not pollution.

They also have an interesting caveat. This is that the way the World3 model works is a through a set of connections that exist within an environment of growth. In an environment of decline, they are likely to reconfigure themselves in different ways. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be a decline—just that the current lines in the model that describe it may not follow quite the same patterns.

But one final note from me. Economists get over-excited when anyone mentions ‘degrowth’., and fellow-travellers such as the Tony Blair Institute treat climate policy as if it is a some kind of typical 1990s political discussion. The point is that we’re going to get degrowth whether we think it’s a good idea or not. The data here is, in effect, about the tipping point at the end of a 200-to-250-year exponential curve, at least in the richer parts of the world. The only question is whether we manage degrowth or just let it happen to us. This isn’t a neutral question. I know which one of these is worse.

2: Updates: Markets, Food, Apple

A: Markets—America’s risk premium

I wrote here recently about the way in which the financial markets were treating the American economy as a risk. We noticed this in the wake of the tariff announcements, when the stock prices fell, but so did American Treasury Bonds. This isn’t supposed to happen: bonds are supposed to be a safe haven when stocks are risky.

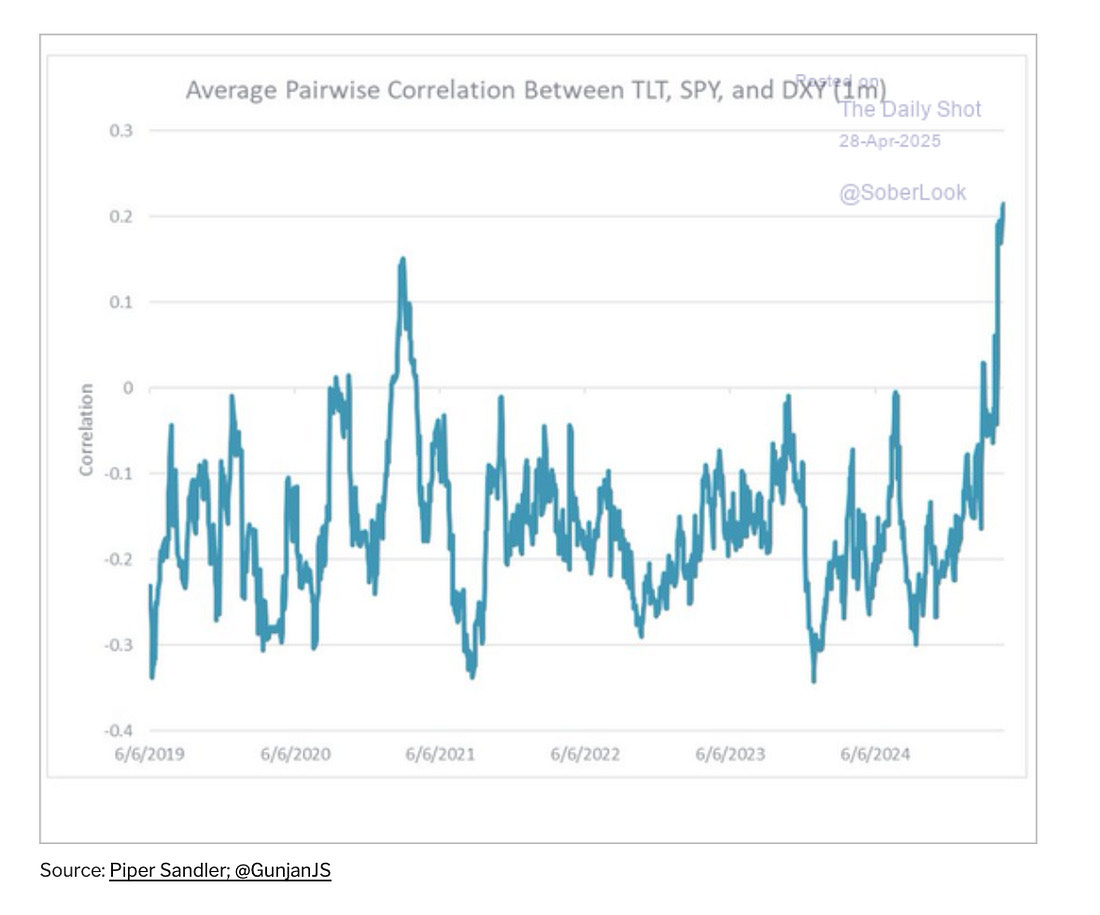

A chart on Adam Tooze’s newsletter Chartbook gives us a sense of the size of the risk premium.

(PiperSandler via Chartbook)

What this graph does is show the combined effects of the price movements of the Standard & Poors 100 (SPY), Treasury bonds (TLT), and the US dollar (DXY). If they were balancing out, the line would still be bouncing around in the middle, rather than heading upwards sharply. (The earlier spike looks to me as if it might have coincided with the January 6th insurrection in 2021.)

In the Project Syndicate newsletter, the economist Desmond Lachman spells out what is going on here:

In moments of global de-risking, investors usually flock toward US government bonds as a safe haven. Not this time: despite the pause in some tariffs, the US dollar and the US Treasury bond market remain under pressure. Moreover, the stock market lost around 8% in value last month, vaporizing around $4 trillion in household wealth.

This kind of volatility can lead to increased financial markets risk, as Lachman spells out:

[P]ast experience indicates that heightened volatility in stock, bond, and currency markets could catch some leveraged hedge fund or equity fund off-side, as happened with Long-Term Capital Management in the 1998. A collapse of that order could lead to considerable strain on the financial system.

Lachman is a former emerging markets economist who is now a Senior Fellow at the centre-right think-tank the American Enterprise Institute. Elsewhere on Project Syndicate, he has described the current American economy as having a lot of the characteristics of an emerging economy, and not in a good way.

Lachman points to the use of tariffs to protect domestic markets; and large budget deficits and a heavy burden of public debt. A government that was trying to increase financial stability would be seeking to reduce its budget deficit rather than pushing ahead with tax cuts.

One other sign that “flashes red” in the emerging markets comparison:

[A] handful of oligarchs wield outsize political influence – or even wield power directly – and when the government goes out of its way to undermine confidence in public institutions in general and the central bank in particular.

B: Food: Norway’s unhealthy food law

I’ve written here several times recently about ultra-processed foods. The food academic Marion Nestle reports on her blog that Norway has just banned the marketing of what she calls “unhealthful” foods to children. The legislation was passed in mid-2023, but has just come into force.

According to the government announcement:

When it comes to products covered by the ban, the most unhealthy products, such as candy, soft drinks, ice cream and energy drinks, cannot be marketed particularly towards children. For other products, such as cereals, yogurt and fast food, limits for different nutrients are used to cover the most unhealthy products in these categories. For example, for breakfast cereals, the content of sugar and dietary fibre determines whether the product can be marketed particularly towards children or not.

The government has basically given legal weight to an existing system of self-regulation, and sharpened it. “Children” covers anyone up to the age of 18. It’s not illegal to sell these foods to them, but it is illegal to market it to them.

The detail is in Norwegian, but Obesity Action Scotland has run a piece on the history of the legislation. Self-regulation clearly wasn’t working:

According to a report from the United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe (2021), "80% of food and drink adverts in Norway promote unhealthy nutrition."

Obesity Action Scotland has also provided a translation:

The ban on unhealthy food advertising will cover all forms of marketing, including television, print, online, and in schools. Products affected by the ban include sugary drinks, salty snacks, and fast food…The regulation will ban the advertising of unhealthy foods that are high in fat, salt, or sugar. It will also ban the advertising of foods that are marketed as being “healthy” or “natural,” if they are high in unhealthy ingredients.

Meanwhile an eight-country study has found that eating ultra-processed foods is likely to contribute to early death. The study is published in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine, and

aimed to estimate the risk of all-cause mortality in 8 countries with different levels of UPF consumption: Brazil and Colombia (low), Chile and Mexico (intermediate), and Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US, where consumption levels are high and UPFs alone account for more than half of calorie intake.

The findings are pretty clear. The researchers found:

a linear association between the ultra-processed food consumption and all-cause mortality, ranging from 4% to 14% of premature deaths, depending on the consumption levels of UPFs in the different countries.

C: Technology: Apple takes a beating in court

(Source: Freepngimg.com)

Just last week, Google took a hammering in court over the way it has used its monopoly of advertising to extract far higher margins than the market would have afforded otherwise.

This week it was Apple’s turn to be on the wrong side of a court ruling. It has lost its case against Epic games. Ars Technica reported that

a federal district court found late Wednesday that Apple was in "willful violation" of a 2021 injunction designed to allow iOS developers to steer customers to alternate payment processors for in-app purchases.

The District Court of Northern California has been holding evidentiary hearings since January 2024, after the Supreme Court declined to hear the case. The judge was scathing about Apple’s conduct—about as scathing, in fact, as the judge was last week about Google’s conduct:

Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers determined that Apple had engaged in a plan to "thwart the injunction's goals," and then engaged in an "obvious cover-up" to prevent that plan from being revealed.

There’s more detail in the story, but Apple’s conduct was such that the judge has referred Apple to the Northern California Attorney General to see if criminal contempt proceedings are appropriate.

"Apple knew exactly what it was doing and at every turn chose the most anticompetitive option," the judge wrote. Apple VP of Finance Alex Roman "outright lied under oath" in testimony about Apple's internal deliberations, according to the court order, while CEO Tim Cook "chose poorly" in actively deciding not to comply with the court's injunction.

The writer and activist Cory Doctorow also covered the ruling in his newsletter. Epic had already won a similar case against Google—it’s one of Google’s three significant losses in court over the last three years—and in fact Apple got off slightly lighter than Google did.

But as with the Google advertising case, this is another case where federal judges have been unwinding the business scams that prop up the vast margins that Big Tech has enjoyed over the past years. It turns out once again that some of the large returns enjoyed by Big Tech are not an inevitable feature of technology platforms, but instead has been the result of a failure of political economy.

Doctorow reminds us that Epic is not a complete good guy here, but that in this case it is on the right side:

[T]he mobile cartel takes 30% out of every dollar, a racket they maintain with onerous rules that ban apps from using their own payment processors, or even from encouraging users to click a link that brings them to a web-based payment screen.

30% is a gigantic markup on payment processing. It's ten times the going rate for payments in the USA, already one of the most expensive places in the world to transfer money from one party to another.

Apple went through a lot of shenanigans to try not to comply with the court’s injunction to maintain its margins. Doctorow again:

Apple cooked up a set of rules for third-party payment processing that would make it more costly to use someone else's payments, piling up a mountain of junk fees and using scare screens and other deceptive warnings to discourage users from making payments through a rival system.

You can see why Judge Rogers might have got a bit cross. In her judgement she had to remind Apple that complying with the law wasn’t optional:

”This is an injunction, not a negotiation... The Court will not tolerate further delays. As previously ordered, Apple will not impede competition. The Court enjoins Apple from implementing its new anticompetitive acts to avoid compliance with the Injunction. Effective immediately Apple will no longer impede developers’ ability to communicate with users nor will they levy or impose a new commission on off-app purchases.”

j2t#638

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.