25 April 2025. Adtech | Debt (part 3)

Google loses another anti-trust case—this time about the advertising market // The distressed debt market helps explain why late capitalism isn’t working [J2T #637]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Google loses its anti-trust case on the advertising market

It’s worth noting that Google has just lost—heavily—an American court case about the way it has manipulated the market for online advertising. While, on this side of the Atlantic, a British legal case has ended in a settlement in which Meta agreed that it did not have the right to serve targeted advertising to an individual.

The Google case has more ramifications, I think, so I’ll start there. It’s also worth noting that Google has now lost three substantive court cases in a row now.

(Google’s stand at Ad:Tech, 2007. Photo: Eric (HASH) Hersman/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

This case was brought against Google by the Federal government and seventeen US States. It is about Google’s control of the software that publishers use to manage online ads, and the ad exchange market. The best single assessment of the Google judgment is probably by Matt Stoller, who has been focussed on monopoly issues in his writing for a few years now.

[T]he gist [of the case] is that every newspaper or website that wants to sell ads pretty much has to use Google’s software to place and match ad buyers and sellers. And the reason is [that] Google has bought a bunch of companies and engaged in practices like tying its products together and excluding rivals from the market by restricting whether its customers can use non-Google services.

The effect of this on the newspaper advertising market is not trivial. Actually, the financial impacts are eye-watering:

As a result, Google’s middleman software services take between 30-50% of revenue spent by advertisers on ads meant for publications, instead of 1-2%. So if the judge finds a good remedy, it could mean billions of dollars more for the press, because Google won’t be able to take nearly as much.

There’s an obvious point that jumps off the page right away. We have been told repeatedly that the reason the US newspaper market has been struggling these past few years—with consequential effects on local accountability and local democracy—was because of some general and inevitable effect of technology change. The world had changed and newspapers were no longer able to compete, etc.

But it turns out that the reason that newspapers were struggling was because of the type of monopolistic behaviour which was the reason that the United States passed the Sherman Act 130 years ago. (In her detailed judgment Judge Loenie Brinkema specifically references breaches of the Sherman Act. )

In his article, Matt Stoller puts the judgment into context. The first is that each of the three anti-trust cases that Google has lost in the last three years relates to a different line of business, but nonetheless they are connected to each other:

In 2023, Google lost a monopolization case to Epic Games over its control of the Android app store. Last year, the company lost a case over its control of search... These decisions build on each other, Brinkema cited the decision in the search case to describe why Google had control over so many small advertisers.

Related to this, these cases now represent a meaningful body of law, and that means that other related cases currently proceeding through the legal system have a stronger body of case law to draw on:

[P]rivate and state antitrust cases, like a case led by the Texas attorney general on adtech currently working its way through the courts, will benefit from this decision.

The second is that the decision in this case has been much quicker than in other anti-trust cases. The complaint here was filed just over two years ago. (The anti-trust case against Facebook/Meta was filed in 2019 but is only now going to court.) One of the reasons for this is that Congress passed a law in 2022 that allowed plaintiffs to choose where to file antitrust cases.

The third is that—like her predecessors in the other two Google cases—Judge Brinkema was scathing about the conduct of Google’s senior lawyer and President of Global Affairs, Kent Walker,

for false claims of privilege and for allowing the wholesale destruction of documents while on a litigation hold.

Brinkema says in her judgment that the court could have sanctioned Google for this, but has chosen not to, because it has found against Google.

Stoller’s assessment of this is that the chances of Google being broken up have just increased. Judges in the three separate cases will be pursuing remedies, and there will be some co-ordination in this. Although the Administration could ask the Justice Department to settle, in this case the other plaintiffs—the 17 States—don’t have to go along with this.

In fact, it must be all go at Google’s legal affairs group at the moment, because the hearing on what to do to remedy Google’s monopoly on search—the second of the three cases it has lost—has just opened in Washington, at the same time as the government’s case against Meta has finally opened.

(Photo: Nancy Scola)

Those two cases are being covered by Stoller in a specific newsletter, Big Tech on Trial, depending on how much detail you want (you get a lot). The Google cases may go all the way to the Supreme Court. In the meantime, the Search case will continue to throw out yet more insight about the way Google’s monopolies work.

It’s possible that Trump will intervene here somewhere along the line, but possibly not. Antitrust is one of the few areas, or maybe the only area, on which there is broad bi-partisan agreement in Congress, which is one of the reasons why these various cases have progressed.

In comparison to the grand guignol in the USA, the British case against Meta/ Facebook feels more like a one-woman show. But it is consequential in its own right. Tanya O’Carroll, who works in human rights and tech policy, sued Meta to stop it using her personal data to target her with advertising. From TechCrunch:

O’Carroll had argued that a legal right to object to the use of personal data for direct marketing that’s contained in U.K. (and E.U.) data protection law, along with an unqualified right that personal data shall no longer be processed for such a purpose if the user objects, meant Meta must respect her objection and stop tracking and profiling her to serve its microtargeted ads.

Meta’s response was, of course, to claim that targeted advertising was not direct marketing, but it settled the case before it went to the High Court. The settlement was significant:

Meta has accepted that under current data protection laws it can no longer use the personal data it has collected on O’Carroll to target her with personalised advertising.

One of the elements that might have influenced Meta not to go to court was that the British Information Commissioner came down strongly on her side before the case was heard.

The business case for personalised advertising as against advertising in general is about the size of the margin, and Meta’s public affairs people were out and about explaining how much it costs to build and maintain these services. But given Sarah Wynn-Williams’ observations about the torrents of money that flow through Meta, perhaps we don’t need to feel too concerned.

If you want to get Meta to stop sending you personalised advertising, you’ll probably have to go through the Information Commissioners Office. But all of this is going to get ratcheted up in the UK soon enough. Liza Lovdahl Gormsen’s class action case against Meta for abusing personal data seems to have cleared the final round of Meta objections in the Appeal Court.

And one contextual note from me. All of this is exactly what you’d expect to happen in the final quadrant of Carlota Perez’ 50-60 year technology/finance S-curve, as the sector becomes mature, regulators catch up, and the sector can no longer make credible claims that it is innovative.

2: The distressed debt market helps explain why late capitalism isn’t working

This is the third part of a series on debt. Part 1 is here; Part 2 is here.

I didn’t intend this to turn into a three-part post, which is one of the reasons there’s been a bit of a gap since Part 2. But the more you look, the more you find, and it turns out that debt and its related artefacts are almost a perfect example of pretty much everything that is wrong with late capitalist economies.

Putting economic pressure on poor and marginalised communities and people? Check. Giving handouts to the financial sector? Check. Encouraging extractive business models? Check.

So in what is definitely the last of these posts on debt, I’m going to look at some of the proposed alternatives, and suggest—in the mildest possible way, obviously—that if you are a cash strapped social democratic government worrying about political challenges from the hard right, that doing nothing is just terrible politics, especially when doing something is more or less cost-free to everyone except the shareholders and senior executives of large retail banks.

I talked in Part 1 about the proposed Fair Banking Act, which is a pretty luke-warm piece of legislation of the “rank and shame” type. It would be better than nothing, but frankly we deserve more.

In Part 2, I mentioned an analysis from 2024 of all of this by Professors Paul de Grauwe and Yuemei Ji, of the London School of Economics and University College respectively.

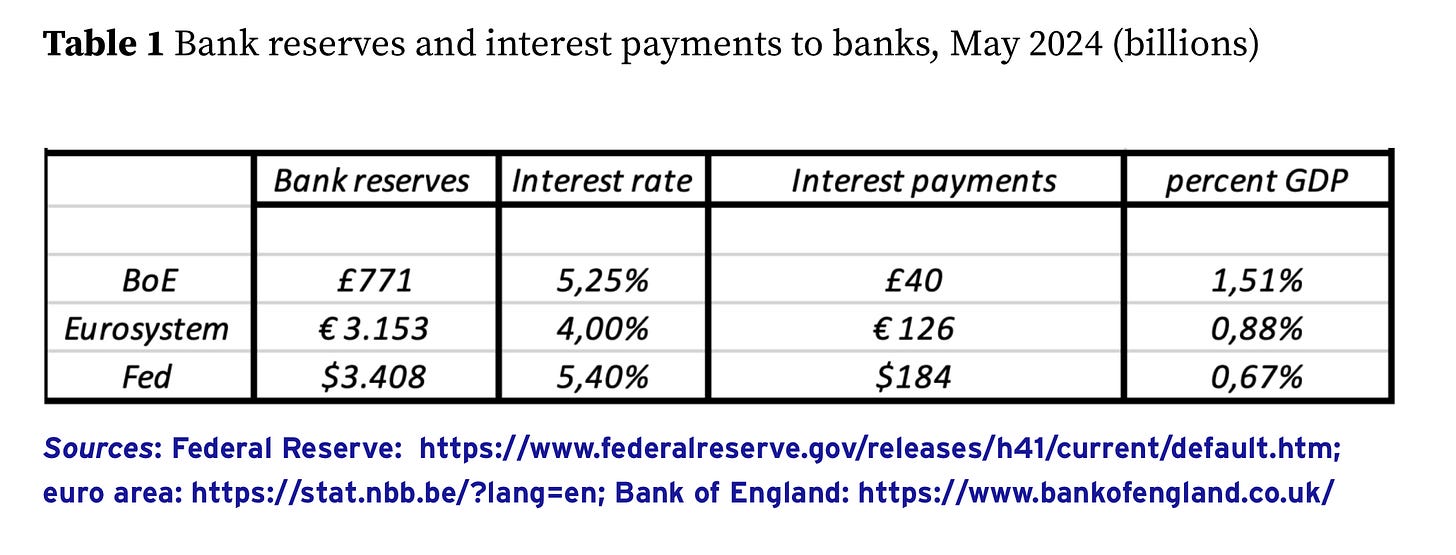

In their analysis, they look at the impact of this transfer on the overall economy, in Britain, the EU, and the United States. The table looks something like this.

(Source: Paul de Grauwe and Yuemei Ji)

In summary, the table looks at annual interest payments, in billions of their respective currencies, and the share these represent of the overall economy (GDP). The UK manages to hand over a greater share of its economy to the banks than either the EU or the USA, partly because it insists on paying interest on all reserves held at the Bank of England by banks.1

It’s not just university professors who think this. The relatively conservative Chris Giles, who writes on economics at the Financial Times, had a piece (paywalled) in the FT last year headlined “An unnecessary subsidy whose time is up.” (The responses in their letters page were a mix of complex technical arguments about monetary policy and some sophistry/special pleading.)2

British policy didn’t used to work like this. In the last post I wrote about the privilege represented by the ability to create money, and that this only worked because the state stood behind it, along with the law, the courts, the police, regulation, and so on. In the old days—before the mid 2000s—the interest accruing on reserves that banks held at the Bank of England as a requirement to have the legal right to trade as a bank used to be sent to to the Treasury.3

It’s hard to argue right now in Britain that the banks have a greater need of £40 billion a year than a whole host of other possible recipients, from schools to health services, especially when the British Chancellor of the Exchequer is lining up cuts to welfare. Even tiering it—paying interest only on reserves above a certain level (as discussed in Part 2)—would free a significant chunk of this money.

This was Chris Giles’ preferred route in his FT article:

Unlike some proposals to change accounting rules or cash flows between parts of the public sector, tiering reserves represents a genuine saving and does not merely flatter the public accounts by creating a hidden liability stored up for future generations.

But I don’t want to get too far away from debt, because in capitalist societies—as Dan Davies says in his book The Unaccountability Machine—debt is a technology of control.

It’s also largely overlooked by economists because it doesn’t fit into their mainstream models. And Davies notes that the amount of debt in the global economy has grown massively since the 1970s:

[T]his might have been the most significant decision that no-one ever made.

What’s interesting about Davies’ account (which looks at business debt, but the point extends) is that it underlines the asymmetries in the debt contract. From the lender’s point of view,:

The lender doesn't have to get involved in the management of the business project, or even have to take a shareholder's perspective in assessing how valuable the enterprise is. All they need to answer are two questions: 'Is the promised interest rate attractive compensation for the time and risk?' and 'Do I think I will get paid the money back?' [216]

And from the borrower’s:

[I]f you aren't able to make the payments, something bad will happen. And every time you make a payment, it reduces your cash on hand... If a system is loaded up with a lot of debt, the need to make the payments becomes a signal that swamps all other sources of information.[216]

And you probably don’t need to be an economist to notice that this increase has gone hand in hand with large increases in inequality in the richer world, although it’s hard to know whether this is causation, correlation, or part of the transmission mechanism.

But the important part here is that is that debt is not a neutral feature of the economy but something that has been designed into our system of political economy in a particular way.

The usual defence of the one-sided nature of the debt contract is that it is designed this way because of moral hazard: that the debtor needs to know they’re on the hook for it because if they’re they’ll be tempted not to bother paying it back. (I realised as I was drafting this piece that this kind of Protestant view of how capitalism works had been ingrained in me almost without me noticing. I kept having to remind myself of David Graeber’s observation that “debt jubilees” were a normal feature of many societies.)

But when you live in a low growth, low productivity, low investment, low wage economy like the UK, debt has become endemic.4 For many, it’s a means of living. As I wrote in part 1, this falls unevenly on some parts of society, on women, people of colour, younger families, and so on.

As the American activist Astra Taylor put it,

Most people are not in debt because they live beyond their means; they are in debt because they have been denied the means to live.

Debt isn’t just a matter of money. Its relationship to poor mental health, for example, is well-known, as is the impact of debt on relationship breakdown. There are significant external costs from debt being a normalised part of the economy.

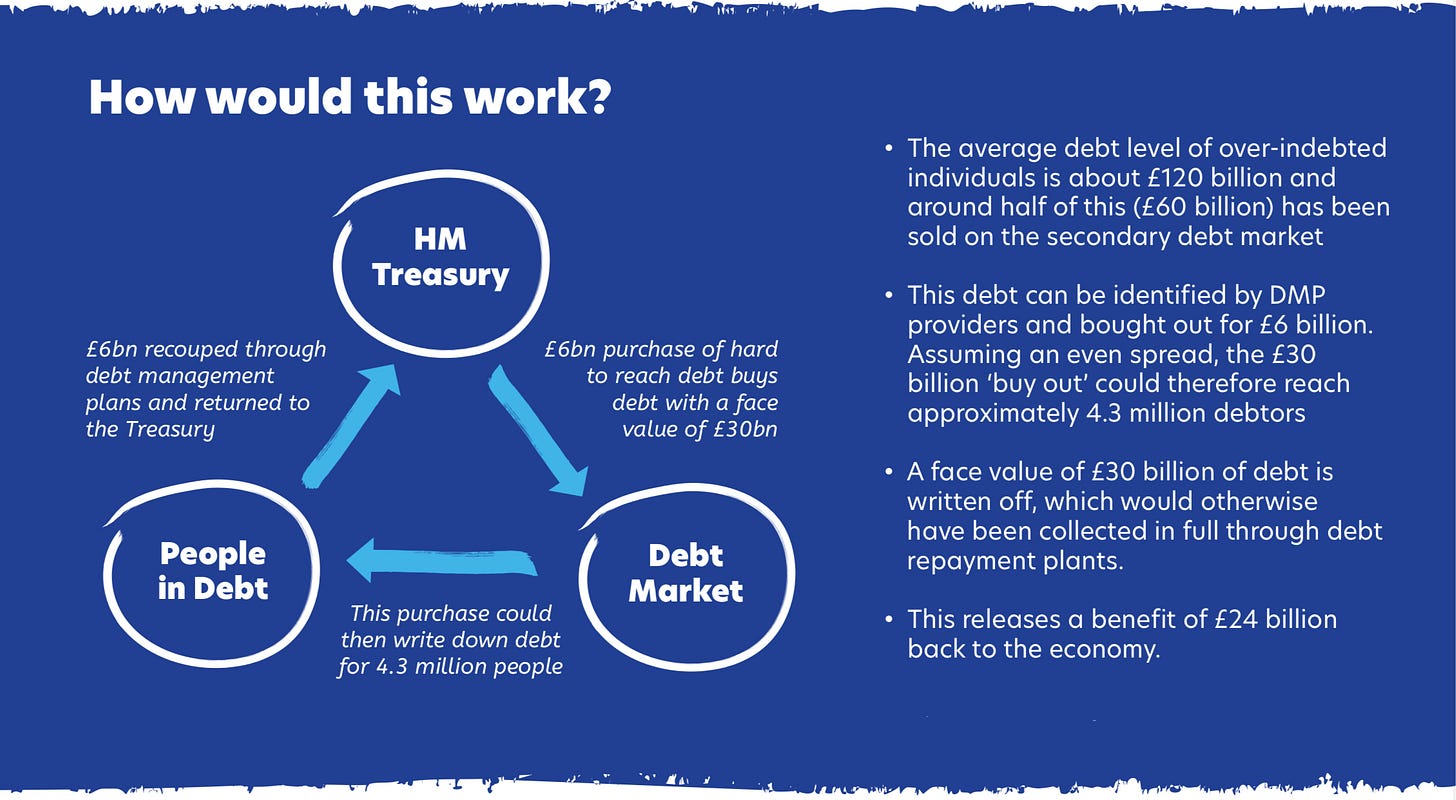

The most radical proposal I found for dealing with this was from the campaigning organisation Debt Justice. Unlike most radical proposals, it is also completely feasible given the underlying economics of both the distressed debt market, and the relationship between the Treasury and the Bank of England.

Before they get to the proposal, the organisation runs through the grim extractive economics of the distressed debt market and the debt management plan. Their graphic spells it out succinctly.

(Source: Debt Justice)

Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is capitalism at its most useless, extracting money from those least able to pay. It is possible to imagine a world where most of this is simply illegal—from being permitted to sell the debt on in the first place, rather than taking responsibility for your own business decisions, to the usurious interest rates and overcharges that get added on to it along the way. (These seem to have been lost in the simplified diagram above.)

Debt Justice has a simple proposal. This is that the Treasury buys up the debt on the secondary or “distressed” debt market (where it sells at 10% of face value), and gets those people whose debt they have bought to repay it at that rate, so the whole transaction washes its face. According to their calculations, about half of the debt of “over-indebted” individuals ends up on the secondary debt market. A handy graphic shows how it works.

(Source: Debt Justice)

But why stop there? Because the first thing the Treasury is going to do is to complain about how expensive it is to manage all those debt management plans and sell it all off again.

The best estimate I got in my research here for the value of the secondary debt market in the UK was around £5.5 billion a year.5 The Bank of England could, for a fraction—literally—of the money it currently pays to the banking system every year in interest charges, simply buy this out and cancel the debt. They could do at scale, in other words, what Martin Sheen did in his television programme for around 900 households (as in Part 1).

Since the banks are the source of the problem—they create money by creating credit/debt—it just makes sure they are paying to sort it out. Working out how much money is released for more productive expenditure by doing this is quite complex, but it could easily be heading for around £25 billion, which is around 1% of Britain’s GDP. In a low wage economy that is struggling for growth, that’s not trivial.

The politics of cancelling debt are also relevant. It creates real benefits in the poorer parts of the economy—exactly those places who feel that the political and economic system has forgotten about them, and who are turning to Reform UK as a result. Formally, given that when you buy someone’s debt, you need to write to them about it, people would end up getting a letter from the government cancelling some of their debt.

Of course, new Labour won’t do this in a hundred years. It hasn’t got the imagination, for one thing, and so far over the course of its first year in office has preferred to hound the poor and schmooze the finance sector. As Chris Dillow wrote recently, when Labour chooses “some parts of capital over others... it is obeying the diktats of the most reactionary segments of capital.”

But: if social democratic governments are going to head off hard-right populists, they need to start by helping those who have been disadvantaged by neoliberalism. Because you’re never going to be able to outflank a hard right party on immigration or welfare cuts. You need to start with political economy instead.

j2t#637

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

This is higher than other quoted figures because it is the actual transfer of money, not the net transfer from the public sector to the private sector.

Some of the latter came from the head of UK Finance, the trade body of the British banking sector. It turns out that he can get out of bed when there’s a scintilla of risk to banking profits but not manage to discuss fairer banking with Michael Sheen, as per Part 1.

I’ve spent some time trying to work out when this change happened in the UK. My best guess is in 2009, when the banks’ balance sheets were in a terrible state after the financial crisis, but I’ve also seen 2006 quoted. If it was in 2009, things have changed since then: the banks’ balance sheets are no longer in a terrible state because the Bank of England has pumped billions of pounds into them through Quantitative Easing.

A 2017 studyfound that 16% of UK adults were in “problem debt”. A 2022 report by Step Change said that 9% of British adults had used debt as a safety net in the previous 12 months, and the press release reported that “the proportion of people struggling is now nearly one in three (30%) GB adults - 15 million people - compared to 15% (7.5m people) who say they were struggling in March 2020.”

That’s £55 billion of bad or distressed debt written down to 10% of face value.