4 April 2025. Cartoons | Debt (part 2)

‘It is good that you are here’ // Where debt comes from (Part 2 of 3) [J2T#635]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: ‘It is good that you are here’

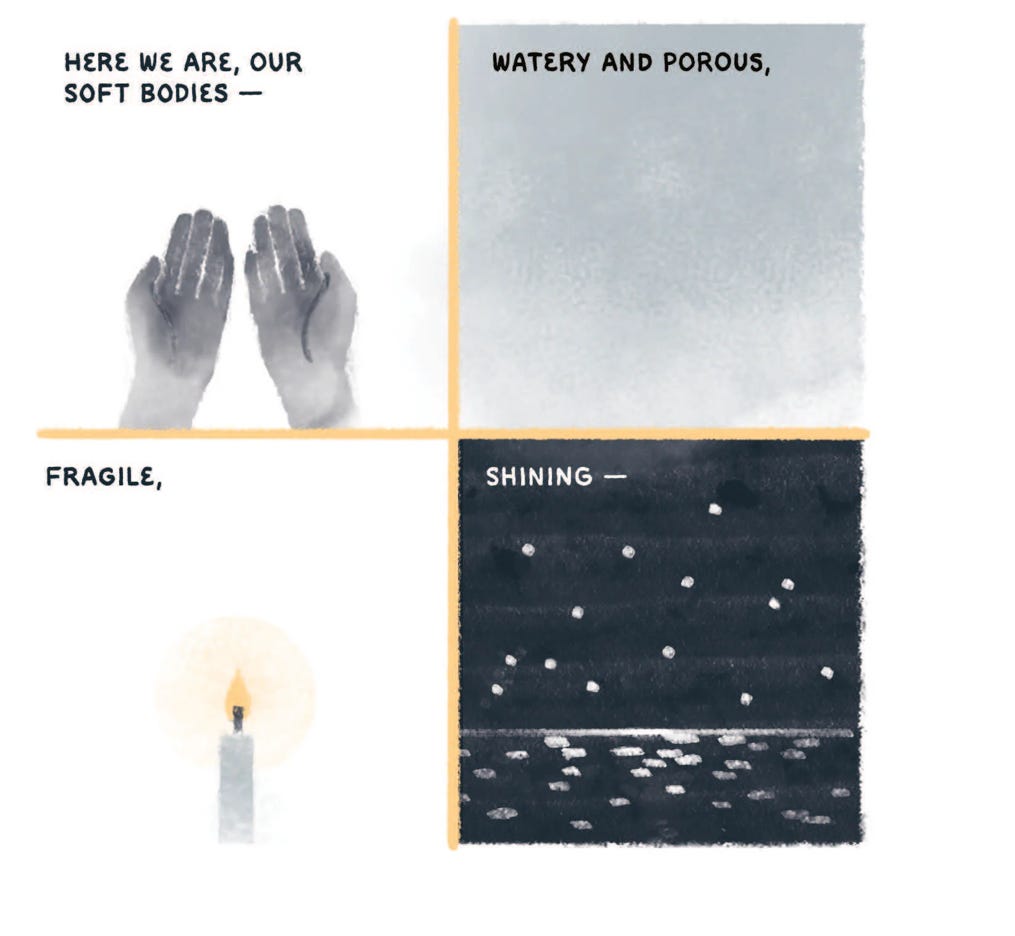

One of the most calming things I have read recently was a set of illustrations by Madeleine Jubilee Saito in the nature and culture magazine Orion, and outside of their paywall.

I hadn’t come across her work before, and on her website she self-describes as a “cartoonist”, but that word doesn’t really convey the spirit of the work, called ‘It is Good That You Are Here’. Orion describes it as “a visual poem”.

As far as I can tell, the work was originally produced when Saito was artist-in-residence at the On Being project.

It’s not a long set of drawings—it will take only a few minutes to read them—and I’m not going to spoil the very deliberate experience she has clearly set out to create by the very deliberate layout and sequencing of the illustrations. But let me share a couple of the images.

(C) Madeleine Jubilee Saito, from ‘It is good that you are here’.

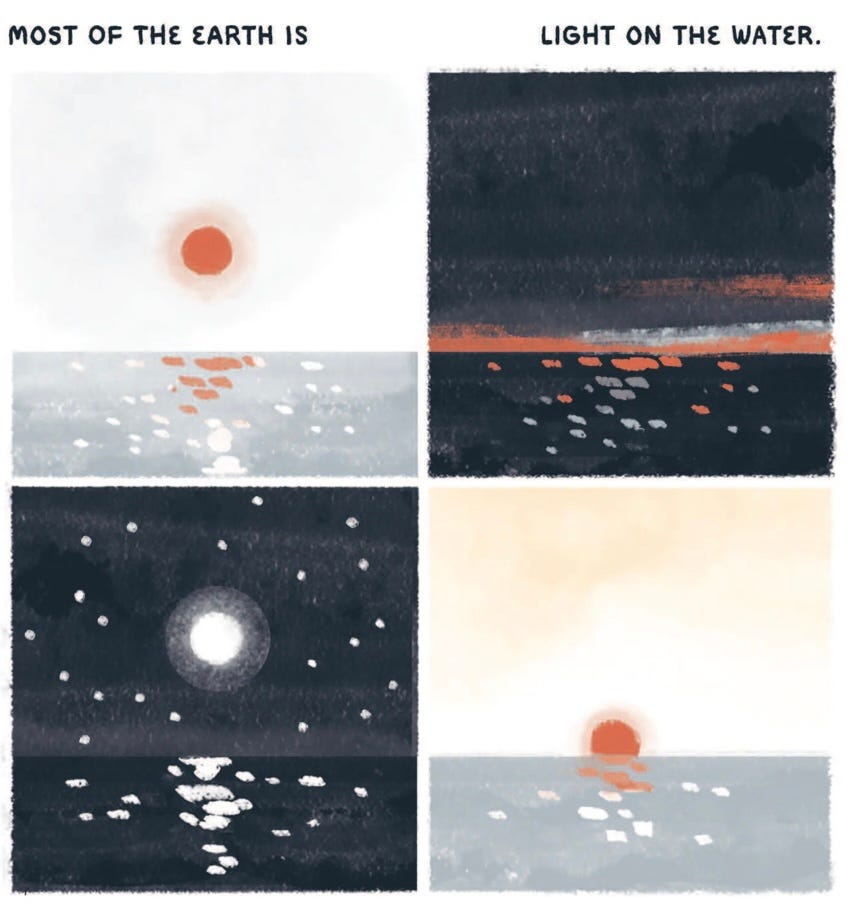

And a bit later in the sequence:

(C) Madeleine Jubilee Saito, from ‘It is good that you are here’.

I probably don’t need to spell it out, but what stopped me short when I was leafing through online—apart from simple effectiveness of the images—was also the sense of perspective, even of distance, that Saito manages to instil into them.

Given the sound and fury of our immediate politics, it was a reminder that the world doesn’t actually revolve around a bunch of narcissists in MAGA caps in the White House.

In an interview in The Comic Journal a few years ago, she talked about her mid-Western background as a source for her work—“I’ve always been drawn to the things that [the cartoonist Art] Spiegelman names as Midwestern—the quietness, the sparseness, the interest in the mundane”—while also acknowledging the “white resentment” that goes with it.

She was attracted to the comic format because of its immediacy:

I've always liked how comics are so irresistible. More than any other medium. Telling your friend about riding the school bus? Very boring. But when you make a little autobio comic about riding the school bus and looking out the window? It's suddenly this very special, memorable event, full of meaning and beauty.

The four panel format is also a deliberate choice, for both formal reasons and reasons of faith. She self-describes as “a Christian and an anti-capitalist”, and the cross between the four panels is—as she explains in the interview—for her a religious motif.

Andrew White, who has co-edited a book with Saito, asks her about images that turn up multiple times in her work:

[T]he best metaphors are infinitely flexible. Like a good metaphor will last you your whole life, and longer. Rivers and oceans and the sun and moon, palm trees and pomegranates—I genuinely believe those images won't ever stop feeling fresh… I often re-use visual rhymes that I like a lot (the rhyme of a moon and a single brightly-lit window come to mind). I hope my readers don't mind. Some things are just nice to draw over and over.

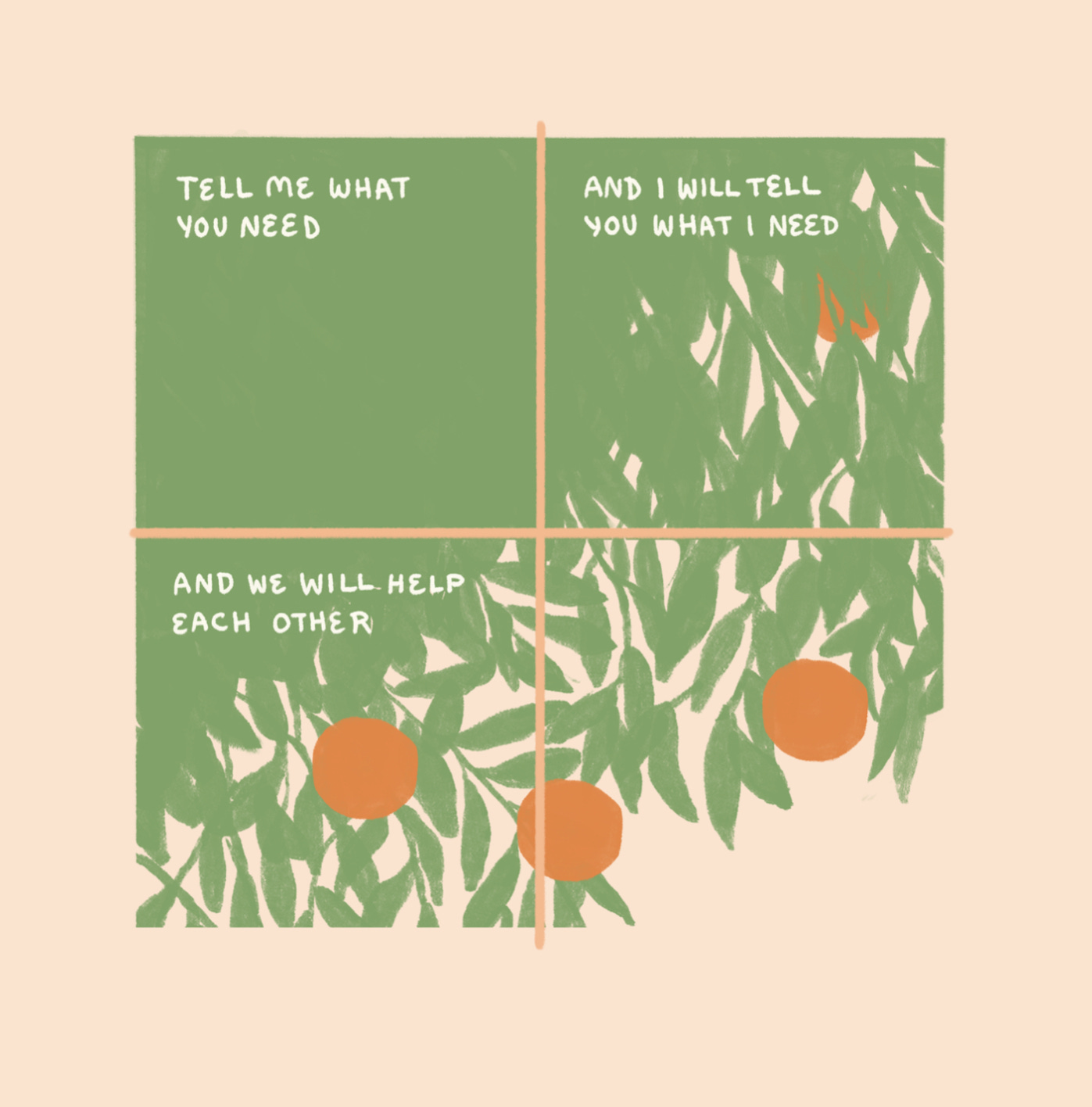

A lot of her work is on her website. Enjoy.

(C) Madeleine Jubilee Saito, from ‘A comfort – 30 days of comics 2018’.

2: Where debt comes from (Part 2 of 3)

In Part 1 of this post, I described Michael Sheen’s Channel 4 programme. The Secret Million Pound Giveaway that involved diving into some of the murky mysteries of the distressed debt market. The programme took more than eighteen months to make, and in of that time, no-one from the British retail banking sector, or their trade body, managed to accept an invitation to speak on camera to Sheen, despite being the originators of much of the debt that ends up in the distressed debt market.

And that led me to think about why that might be. And it turns out that the creation of debt is at the heart of the banks’ business model, and that if the government wanted to get the banks to do something about improving debt outcomes in the UK, they have all of the levers they need to make this happen.

Given that “the purpose of a system is what it does”, and none of those levers seem to get pulled, you have to assume that the system is happy with a Britain in which the poor are overloaded with debt.

In this post I’m going to walk through some of the political economy of this, and it might be a bit technical in places, but bear with me.

The closest that Sheen’s programme came to discussing this was in a conversation with the former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, where he reminded us that the banks had been bailed out to the tune of billions by the British state to stop them going bust during the financial crisis in 2008. The implication was that they might have some social obligations as a result.

(The run on Northern Rock, 2007. Photo: Lee Jordan, CC BY-SA 2.0.

There’s two important building blocks here.

The first is that the way that money gets created in the modern state is not by printing it, but by banks creating credit—or, to put it another way, since a balance sheet has to balance—by creating debt.

The second is that British banks are obliged to hold reserves at the Bank of an England as a condition of doing business. In exchange they get what amounts to insurance against bankruptcy from the central bank, effectively underwritten by the British state.

Actually, there’s a bit more to this. The banks get paid interest on all of these reserves at the current Bank of England base rate. Unlike most insurance schemes, in other words, they also get paid for being insured. (There’s a rationale for this which I’ll get to later.)

As I say, all of this is a bit technical, but it is worth spending some time on. In his recent popular economics primer, Why We’re Getting Poorer, Cahal Moran reminds us that:

Most of the money created in a modern economy is done so as credit by private banks... When credit is granted it is a way of bringing resources from the future into the present.1

There are a couple of corollaries to this, both of which are important when it comes to discussing debt. The first is that every credit creates a debt; and that creating money by creating credit/debt works because the debt is created in a ‘fiat’ or state-backed currency which only exists because the state stands behind it. It is legal tender only within the boundaries of the state.

(Hyman Minsky. Photo: Pontificador/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Or, as the economist Hyman Minsky put it:

Everyone can create money; the problem is to get it accepted.

Other business sectors expect to pay for their raw materials, and there is certainly a cost to creating the conditions in which “money” is created by the banks. But if you are a a bank, you get your money for nothing. It wouldn’t be a crazy idea to impose some kind of transaction tax on the creation of new debt, to represent the public’s investment in the conditions that make its creation possible.

Because, right now, the costs are the socialised and the profits are privatised, which is more generally a characteristic of the financial sector in the UK.

The second corollary is that the institution making the loan needs to have a reasonable belief that the individual or business is in a position to repay it—or more broadly, that the economy has the capacity to support the value that is being created through the creation of the debt. (Otherwise, the banks could just issue millions of pounds-worth of credit and we’d all be millionaires.)2

There are two important observations here, one positive, one negative. The positive one is from the great economist John Maynard Keynes:

Anything we can actually do we can afford.

If there is spare capacity in the economy, the government can create debt to get that capacity utilised again. There will be multiplier effects. Economic activity begets economic activity: a national economy is not a credit card.

The second one is that, at an individual level, the banks should not advance credit to people whom they don’t believe can pay it back. At the moment, this system is hopelessly asymmetric: the blame for failure in repayments falls entirely on the individual. The lender has, at least, a moral obligation in the transaction that goes missing in the system.

That’s the first half of all of this. To spell it out: The creation of debt in the UK economy is a unique privilege for the banks, which comes with large private benefits but no apparent social benefits.

The second half takes us into the world of fractional reserve banking. This is one of those bits of economics that you learn quite early on: that if everyone who had deposited money in a bank wanted to withdraw all at the same time, the bank would go bust. This is because they are also lending most of it out.

Instead they hold a fraction of their reserves, and they are required to deposit some of these at the Bank of England, as a condition of doing banking business in the UK. This proportion increased after the 2008 financial crisis, when the authorities realised (with the collapse of Northern Rock) that banks were taking risks by reducing the size of the reserves they held.

(The Bank of England. Photo: Images George Rex, CC BY-SA 2.0.)

So these Bank of England deposits are a form of insurance to make sure that the banks don’t take risks with the money that has deposited with them. But in the UK, the Bank of England then pays interest on all of this at the current base rate. One recent analysis of Bank of England policy said,

Assuming a long-term neutral rate of interest of 3%, this means that in steady state the Bank of England is expecting to pay out £10-15 billion a year to banks indefinitely.3

You can look at this in different ways. You could say that it’s just a “stealth subsidy” to the banks, and this is the argument that has been made by the new economics foundation. In the Euro area, the central bank requires banks to hold a minimum of 1% of reserves with them, and this 1% does not attract interest payments. In Switzerland this figure is 4%. This is known as tiering.

So, in theory, if you wanted to underwrite (say) a system of fair community credit, given the failure of the banking system to do this, you could divert the interest payments from (say), the first 10% of the deposits held at the central bank. This would be a transfer from retail bank investors to some of the poorer and financially disenfranchised parts of the country.

The last time he opined on it, the present Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailie, said he thought that not paying interest rates on all of the banks’ deposits would be a bad idea. He said that it would make the banks less sensitive to changes in interest rates and therefore would make monetary policy less effective.

You might consider that this is another example of the British state privileging the interests of the financial sector, as it has done for the last 150 years, and you would probably be right about this.

But given that other countries don’t seem to feel the same need, and their monetary policy still seems to work, this is, at least, a testable hypothesis. You could start at withholding interest payments on the first 5% or 10% of reserves and see if it makes any noticeable difference.4

In the next and last post in this series, I’ll look at some of the alternatives, and the political rationale for them.

j2t#635

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

This is not a controversial or disputed account of how money gets created.

Actually, this would lead to hyper inflation, and we’d only be paper millionaires.

These are net figures, measuring the overall transfer of monies from the state to the banking sector. The Bank of England earns some interest on the monies deposited with them by the banks. The actual transfer to the banking sector is higher. It’s also worth noting that when interest rates were negligible, it was because the banks were being underwritten by a vast public programme of Quantitative Easing.

My guess is not: interest rates are a pretty crude economic lever. And some academics think Bailey’s claim is actually wrong.