11 April 2025. Trump | Facebook

Special ‘stable genius’ edition on Trump’s tariffs // Facebook is everything that you thought it was. [#J2T 636]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: It is just about possible to understand Trump’s tariffs, but you have to dig deep to get there

I’ve been digesting tariff chat for the past few days, like everyone is, and trying to make sense of the political economy of it. ‘Make sense’ as in trying to piece together the MAGA mindset and then think it through, beyond the economics of it. And just as I had a piece all but written, the Administration turned around and ‘paused’ most of the tariffs it had imposed.

If you do want a straight review on how tariffs work, and don’t work, Noah Smith has a good explainer. Kyla Scanlon also does a Q&A (thanks to The Browser for this link).

But before I get to the heavier end of the content, let’s turn to the Bloomberg newsletter, in which Jessica Karl treads smartly but lightly over what’s happening in the world. On this occasion by quoting a Bloomberg editor on GenZ slang:

(Source: Heather Landy, LinkedIn).

That also seems to be how the world has responded to the initial announcement, perhaps because the randomness of the numbers created suspicions that the White House policy was based on asking an AI.1 One of the metaphors about Trump that’s been used in the past that seems to have stuck in his second term is of the gangster—even in the pages of the Financial Times.

And that doesn’t seem to have been far away from the commentary, or come to that, in some of the online justification. Donald Trump Jr, for example, online shortly after the tariff announcements last Thursday, said that you wouldn’t want to be last country to negotiate with America over tariffs. I also liked the article—I’ve mislaid the link—that pointed me to The Sopranos as a metaphor for what was going on:

There’s a lot going on here, so I’m going to try to parse it out. I’m going to start with the rationale, and if I have space, look at some of the political economy here. There’s another piece to be written here, on long waves of change and the global moment that we’re in, but that’s for another day.

The rationale

Trump, in general is obsessed with material goods, and not so much with services. So he obsesses about trade deficits, and doesn’t notice the large service surplus that funds them. (Or that America, pretty much uniquely, exports dollars for use as a reserve currency by other countries, which effectively also subsidises the US.)

Hence his notion that every other country in the world is “ripping off America.”

Noah Smith suggests that this is because his economic advisers have misunderstood, deliberately or not, the basic equation for Gross Domestic Product [GDP] that people learn the first time they do economics:2

The formula is Y=C+I+G+(X−M), where C is consumption, I is investment, G is government spending, X is exports, and M is imports.

So it looks obvious: if you get rid of that -M, you’re that much richer. But as Smith reminds us, this is just a way of tidying up the data, because consumption, investment, even government spending, all include imports, but they’re harder to measure there: much easier just to count the imports as they come in and deduct them from the total.3

There’s a second assumption that sits inside the White House worldview: that if all of those imports stop coming in, then American companies will start making those goods themselves. Well, the best answer to that is: it depends. In a world of complicated goods and complex supply chains, it is much less likely than it used to be. In the Financial Times, their veteran economics writer Martin Wolf reckoned that the shape of trade in goods with America would mostly remain the same even after the punitive levels of tariffs announced last week, but there would just be less of it.

(Image posted to Twitter/X by GabeFin)

But even if American companies filled the gap, there would be a delay. It takes time to build capacity, skills, products, markets, and so on.

The other thing here is that in terms of the overall American economy, manufacturing production—which is what all of this is about—is small beer these days. It makes up 8% of the US economy. Even if single one of the manufactured goods that are currently imported into America was made in the United States instead, that figure would climb to... 9%.

What’s going on

So this is a lot of chaos, even with the “pause” announced on Wednesday, for a tiny and possibly hypothetical gain.4 It’s not exactly smart policy. You’re left with several choices about what’s going on.

The first is that the White House genuinely doesn’t have a clue: Trump is obsessed with tariffs, and always has been, and his cast of MAGA sidekicks see it as their job to go along with what the President wants. It is a tiny talent pool, after all. We’ll come back to the ideological point in a moment.

The second is a reminder that we are dealing with a man who told an aide during his first term that he needed to “win” something every day. “Win” as in having stories about him that put him in the spotlight and made him look good. The attention is the message. This makes for lots of tactical noise and no strategy.

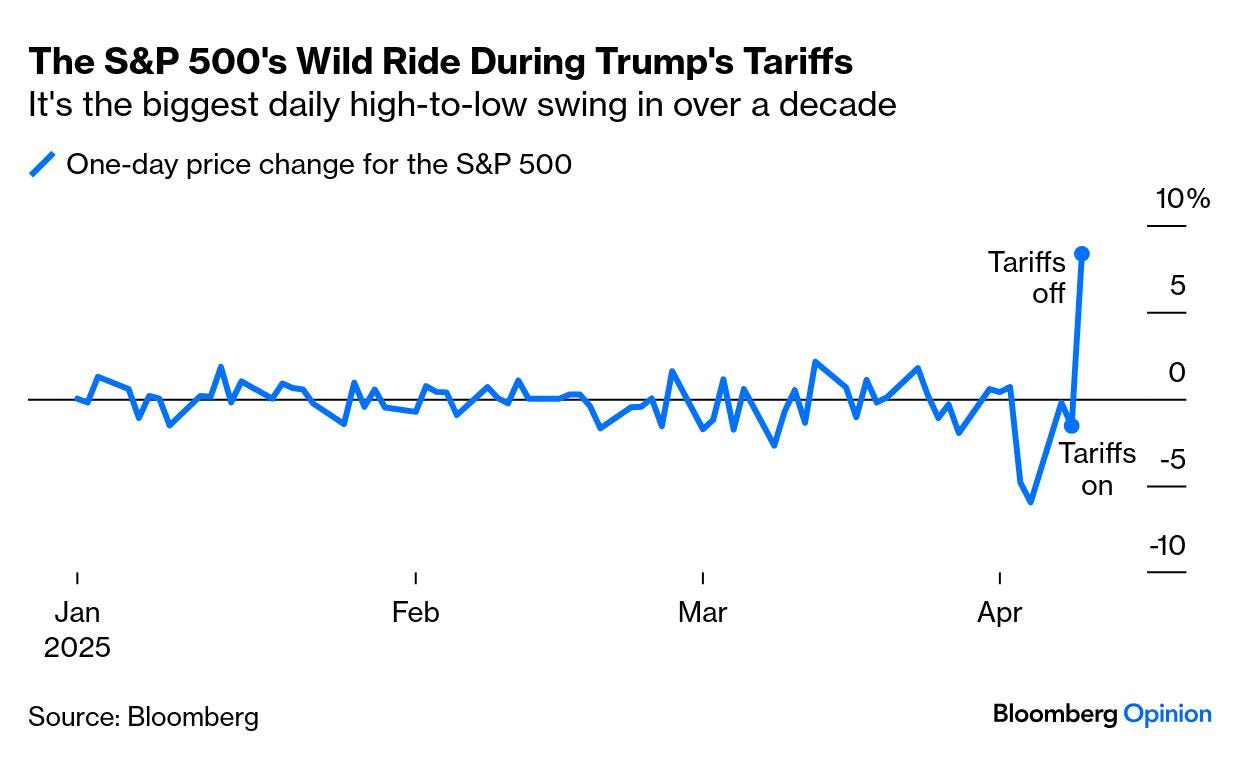

Then there’s the thought that it might all have just been an insider trading play. The stock markets headed down, fast, in response to the original tariff announcements. They didn’t recover. When the “pause” announcement was made, they picked up again quite quickly.

(Source: Bloomberg.)

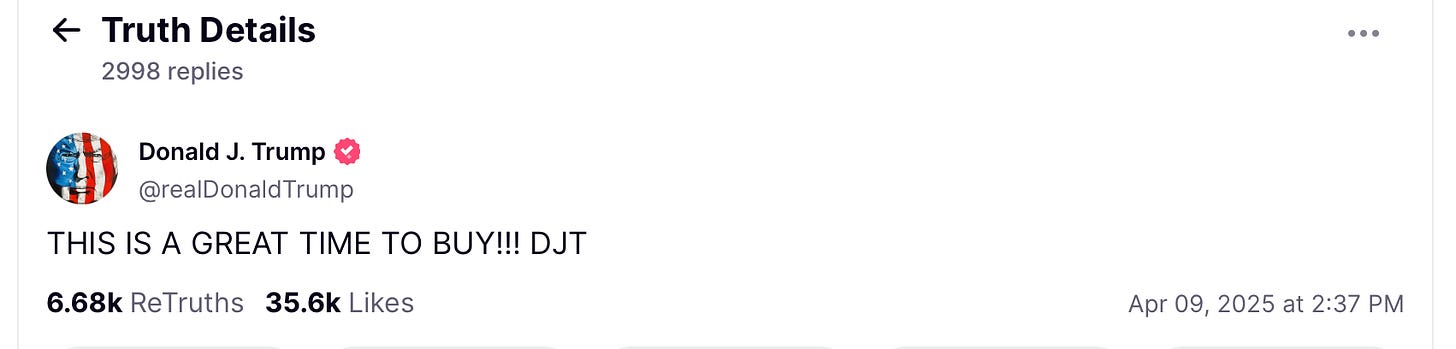

So someone who sold at the right time and bought at the the right time would have done pretty well. Of course, there used to be rules to stop politicians doing that in the US, but one of the first things the Trump administration did was to remove them. Anti-corruption measures are for the little people. And here’s Donald issuing share tips just before the “pause” announcement on his Truth Social platform:

I’m sure some of this happened, but I don’t think it is the reason it happened.

Income tax

What seems to sit behind Trump’s obsession with tariffs is that he hates income tax. He said as much in his so-called “Liberation Day” pronouncement, as Heather Cox Richardson noted on her currently unmissable blog:

"You know, our country was the strongest, believe it or not, from 1870 to 1913. You know why? It was all tariff based. We had no income tax.”

Of course, this is a total misreading of history:

[T]he Panics of 1873 and 1893 devastated the economy, few Americans at the time thought the Gilded Age was a golden age... Congress passed the 1913 Revenue Act imposing income taxes to shift the cost of supporting the government from ordinary Americans, especially the women who by then made up a significant portion of household consumers, to men of wealth.

In brief, then, tariffs, then as now, fell disproportionately—in effects as a sales tax—on working-class Americans. Income taxes did not. The logic here is that same logic that ensures that Trump administrations are willing to go into debt to give tax cuts to the wealthy.

The other missing piece in this is that the cost of government was tiny in the later part of the 19th century, and manufacturing and resources was a much larger part of the economy, and not just in America.

But at least this is of a piece with other parts of MAGA thinking: the hatred of Woodrow Wilson as the architect of “totalitarian government intervention”, which has only been extended over the course of the century since, and the assaults on the administrative state.

[Update] This point about income tax was underscored by the Democrat Senator Elizabeth Warren in an article by John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

In our conversation, Warren underscored that the Republican desire for tax cuts seems to know no bounds. “Even in the middle of this chaos, they are moving forward on a bill that has trillions of dollars in giveaways to corporations and billionaires,

But leaving aside all of the other issues around tariffs, even if the imposition of tariffs worked, the revenues would be a tiny fraction of the funding needed by a modern government.

Markets

It’s not yet clear what prompted the “pause” on Wednesday night, but the most likely explanation is that as well as selling stocks, people were also selling American Treasury bonds. It’s not supposed to work like this—normally investors turn to Treasuries as a safe haven for their money when stock markets are volatile. Without going into the technicalities of this, when investors buy bonds, and their price goes up, it means that the US government is paying less to service its loans and debts.

Because investors were selling rather than buying, the cost of servicing government debt was going up rather than down, possibly because the market crash was squeezing some financial sector players. This seems to have been the moment when the White House blinked. John Cassidy, again, on Thursday:

Lawrence Summers, a former Treasury Secretary, warned online that “developments in the last 24 hours suggest we may be headed for serious financial crisis wholly induced by US government tariff policy.”

There’s lots more here, but the bigger point is that there’s no such thing as a “free market”. All markets are underpinned by some combination of laws, contracts, social institutions and social relationships. And one of the things that seems to have spooked investors—apart from the randomness of the tariff announcements and the strange calculations that sat behind them—is the lawlessness of the current Administration.

Given Trump’s personal business history, I’ve seen it suggested that investors may have also feared that the Administration might just default on some its debts.

China

The “pause” on tariffs didn’t extend to China. Gangsters need to find a way to save face when they back down. But doubling down on China seems like it might be a mistake. If any country in the world understands the intricacies of global supply chains, it’s China.

China responded to the tariff announcement by announcing new licensing arrangements for exports of a series of critical minerals—samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium. Michael Barnard described them as

the elements that don’t make headlines but without which your electric car doesn’t run, your fighter jet doesn’t fly, and your solar panels go from clean energy marvels to overpriced roofing tiles.

In other words, they target, very specifically, defence, advanced manufacturing, and cleantech. Barnard goes into some detail on each of these in the piece. It’s not a ban. It’s just paperwork. But the person who made the decision knew what they were doing:

They’re chosen with the precision of someone who’s read U.S. product spec sheets and defense procurement orders... They didn’t need to say no. They just needed to say “maybe later” to the right set of paperwork.

It’s more sophisticated than that, because the licenses ensure that China will learn a lot about who is using these materials, and for what reasons. Eventually the US might be able to source some of this from elsewhere, but not quickly. In some of the commentary I’ve seen, it’s suggested that this isn’t even a “retaliation” by China. It’s more like an opening shot across the bows, by way of a gentle reminder.

2: Facebook is everything you thought it was

I have been meaning for a while to write about Careless People, the account by a former senior Facebook staffer about her six years at the company. There are reviews at both Daily Maverick and 404 Media that pick up on different aspects of the book.

Sarah Wynn-Williams is a former diplomat from New Zealand, who was Facebook’s global public policy manager from 2011 to 2017. She left the company after making allegations of harassment. Facebook went to court to try to prevent the book being published. Wynn-Williams is unable to talk about Careless People because of a current gagging order from a third-party arbitrator after Facebook argued that it violates “a non-disparagement clause” in her contract.

Facebook, of course, would have us believe that the circumstances of Wynn-Williams’ departure make her an unreliable witness. On the other hand she comes with documents, as Rebecca Davis writes in the Maverick:

Lots of them. Internal emails, memos, messages: some written by Zuckerberg and COO Sheryl Sandberg. It’s this documentary weight that gives her gossipy, fast-paced narrative its punch.

Facebook, Wynn-Williams discovers, is unlike any other company. Huge amounts of wealth flow through it, and people are very well paid. But they are also paid according to “tenure as much as title”, and because of this, junior staff can be worth more than their bosses. But before you decide to apply, this has a price attached.

This compensation comes at a considerable personal cost: employees are expected to answer emails at any point between 5am and 1am the following morning.

Some of the detail is eye-rolling:

Facebook’s top management team, for instance, ensures that Zuckerberg wins every board game he plays. Zuckerberg requests that the global team arrange for him to be “gently mobbed” by a crowd in Indonesia for a kind of ersatz rock god experience. He pairs this with karaoke on his private jet, where his team dutifully cheers him on in his rendition of the Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It This Way”.

Of course, given her role as global public policy manager, Wynn-Williams had a close up view of Facebook’s interaction with governments at a time when its influence on elections was, bluntly, far too large.

This is a good moment to bring in Jason Koebler at 404 Media, whose article is headlined, “Careless People is the book about Facebook I’ve wanted for a decade.”

The reason for this is that he’s been covering Facebook for about that long, and after a series of critical articles, the company invited him to its Menlo Park headquarters to talk to the content moderation team. He asked the then Head of Product Guy Rosen about the way in which its content moderation had failed so completely in Myanmar that it could be “credibly accused” of facilitating the genocide of the Rohingya people:

Rosen said that Facebook’s content moderation AI wasn’t able to parse the Burmese language because it wasn’t a part of Unicode, the international standard for text encoding. Besides having very few content moderators who knew Burmese (and no one in Myanmar), Facebook had no idea what people were posting in Burmese, and no way to understand it.

At the time, Facebook had been operating in Myanmar for seven years.

The biggest question I had for years after this experience was: Does Facebook know what it’s actually doing to the world? Do they care?

Careless People, says Koebler, helps him to answer that question.

[A]s a memoir, it does something that reported books about Facebook can’t quite do... She was in many of the rooms where big decisions were made, or at least where the fallout of many of Facebook’s largest scandals were discussed. If you care about how Facebook has impacted the world at all, the book is worth reading for the simple reason that it shows, repeatedly, that Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook as a whole Knew. About everything.

(Mark Zuckerberg in 2023. No doubt still winning at board games. Photo: Anurag R Dubey, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

Wynn-Williams’ role as Global Director of Public Policy eventually involved setting up meetings with world leaders for the Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and the Chief Operations Officer Sheryl (“Lean In”) Sandberg5, deciding on the policy and strategy for these meetings, and flying to negotiate with governments about unblocking Facebook, as she did in Myanmar.

Rebecca Davis is interested in Facebook’s relationship with politics, and her article has more in it than I can reproduce here. But in 2010, Facebook discovered that adding an “I voted” button had got an extra 300,000 people to vote in the American mid-term elections, and that seems to have opened the floodgates. By 2014,

A new team was built to woo politicians around the world, to train them how to use the platform effectively — and to subtly remind them that their re-election campaigns would go better if Facebook liked them. Or, more precisely, if the algorithm did...

“Facebook rewards outsider candidates who post inflammatory content that drives engagement,” writes Wynn-Williams. Worse: “We charge less money for ads that are more incendiary and reach more people.”

The book has an account of how in 2016 Facebook allowed three different micro-targeted voter suppression campaigns against different groups of Democrat voters. These campaigns were invisible to the wider public:

When Zuckerberg and Co are confronted with the consequences of their product after Trump’s win, they are less remorseful than furious. Particularly Zuckerberg, who fumes after a dressing-down from Barack Obama about “fake news”, and is deeply resentful about what he sees as unfair media criticism. So much so that he begins scheming ways to “crush” the press entirely.

The reason Koebler welcomes the book is because reporting on Facebook basically involves being endlessly gaslighted by the company. Wynn-Williams’ book tells him that he had the story right; that Facebook was exactly the careless and destructive and lying company that he thought it was. An extract from Careless People posted with the Maverick article certainly confirms this.

It’s possible to be sceptical about Wynn-Williams as a narrator here, not because she was fired after after making a harassment allegation, but because she did this job for six years when Facebook was up to its eyes in all of this stuff and it took her that long to leave. Wynn-Williams discusses this in the book—both reviewers touch on it—and you probably have to make up your mind on this for yourself if you read the book.

She also left quite a long time ago—long enough for Facebook to claim that her allegations were “old news”. Which is perhaps more revealing than the company intended it to be.

But at the end of their very different pieces, these two writers come to very similar conclusions.

Here’s Ward:

[W]hat she offers is invaluable: a granular, infuriating, and often absurd portrait of a company with terrifying reach and no moral compass.

And here’s Koebler:

It has been years since Wynn-Williams left Facebook, but it is clear these are the same careless people running the company... It is obvious why Facebook doesn’t want people to read this book. No one comes out looking good, but they come out looking exactly like we thought they were.

j2t#636

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

This is explained by The Verge. Alex Tabarrok thinks they could have used better prompts.

The famous Upton Sinclair quote comes to mind here: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

If this seems technical, imagine a barren island with a lighthouse on it. The island produces nothing, and everything the lighthouse keeper needs has to be shipped in by boat. The island’s GDP is zero: all of the lighthouse keeper’s Consumption is covered by Imports.

The “pause” still leaves 10% tariffs on American imports, more on some categories of goods, and a hike on the tariffs on China. The decision seemed to have been made so quickly that the White House wasn’t able to give clear answers on the detail.

Leaning in apparently included Sandberg asking female executives to share her bed on the corporate jet when on business trips.