26 October 2024. Capitalism | History

Maybe capitalism is killing itself through low growth // History as lessons, history as inspiration [#611]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: Maybe capitalism is killing itself through low growth

At his Stumbling and Mumbling blog, Chris Dillow asks if capitalism is now creating low growth. He’s focussed on the UK, and you have to wade past some parochial points about the recently elected Labour government to get there (not that I disagree with these), but the broader argument is definitely worth rehearsing here.

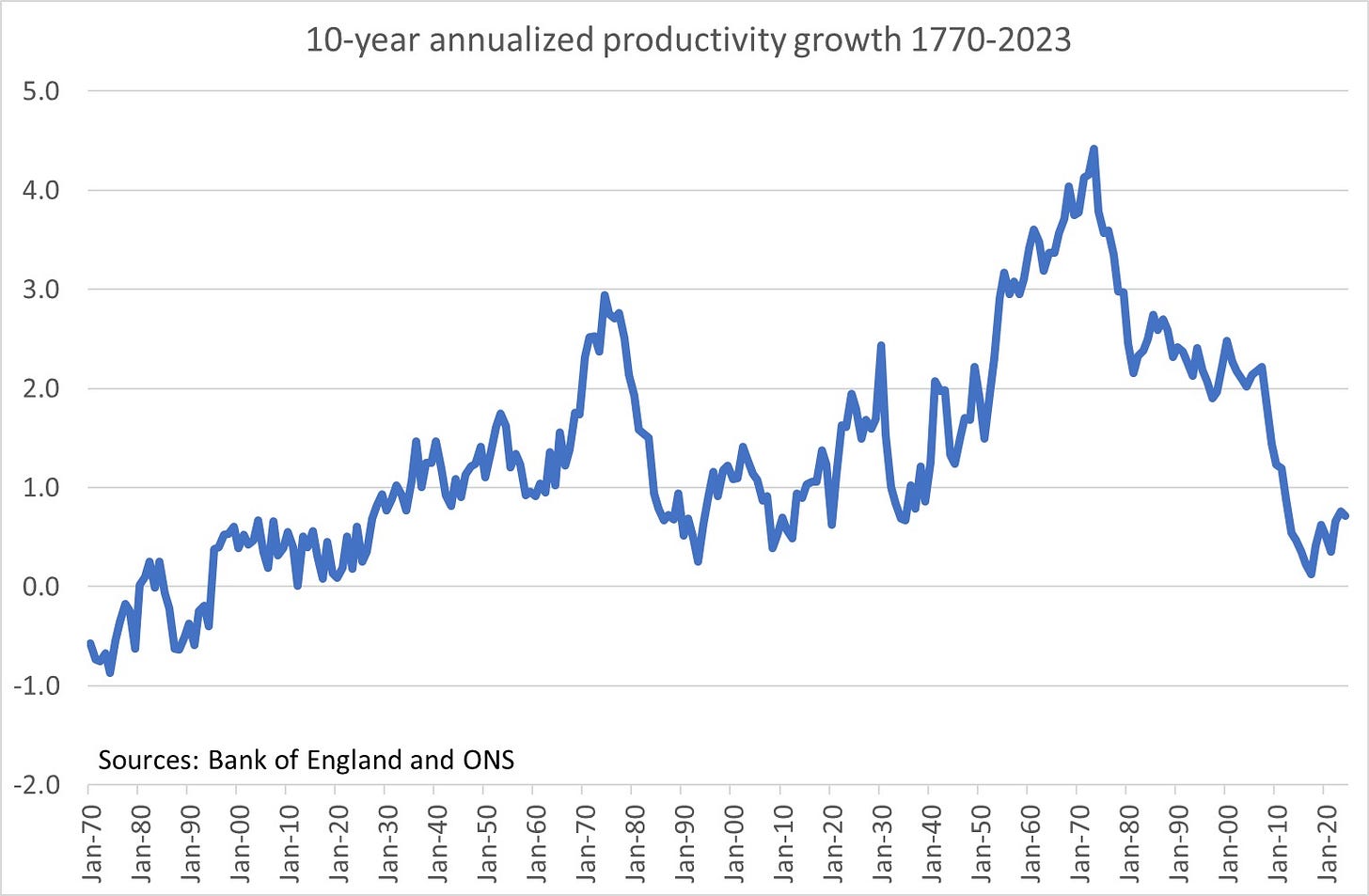

The UK data shows that the rate of growth in productivity levels in the British economy has plummeted since the global financial crisis. Here’s Dillow’s chart on this:

(Bank of England. ONS data. Chart: Stumbling and Mumbling)

In case you’re wondering, this a ten year annualised rolling average going back to 1770: not quite the beginning of British capitalism, but not far off.1 The downward slide in productivity growth since the 1970s is striking.

Dillow thinks there are five forces that have slowed growth in productivity, although some of these are connected. Most of these stretch beyond the UK. I might as well run through them.

'[P]rofit rates have fallen thereby reducing incentives to invest’

[W]hat matters here is not just current profit rates (which are hard to measure because the capital stock is hard to measure) but expected ones. It's reasonable for companies not to invest in new technologies if they fear that future progress in AI or robots will render those investments unprofitable.

Dillow references research by William Nordhaus that says that “companies captured "only a miniscule fraction" of the social returns from technological advances between 1948 and 2001 because profits were indeed competed away.” So managers at individual companies would therefore be reluctant to invest. (In practice this is an argument for the importance of public investment.)

’ [R]ising rents are crowding out other forms of economic activity.’

Rents here are the proportion of economic activity that is extracted by owners, rather than being generated by productive economic activity. Dillow’s posts are always heavily referenced, and so here’s his description of this.

We're handing so much money over to owners of prime residential or commercial land, to owners of oil and gas fields, intellectual property and infrastructure that there isn't enough left to create enough demand for dynamic sectors of the economy.

He also references the research of Brett Christophers, who has looked at the way the British economy has been captured by rentiers. (I’ve written about Brett Christophers’ work on Just Two Things before, by the way).

The growth of service industries as a share of the economy

This is a long term trend in richer economies (actually, in middle income countries as well) and the productivity problem it creates is known as Baumol’s Law. The post quotes the economist Dietrich Vollrath on this:

Most service industries have relatively low productivity growth, and most goods-producing industries have relatively high productivity growth. As we shifted our spending from goods to services then, this pulled down overall productivity growth. (Fully Grown, p5).

I sometimes wonder about this, since there’s some evidence that you can improve productivity in some service sectors, but not if you apply command-and-control models to them. But it is true that there are limits to this.

Capitalist inequalities, of both income and power, can themselves slow growth

It encourages the rich to invest not merely in increasing aggregate productivity but in methods to protect their privilege and power - be it in guard labour (pdf) such as supervisory staff, technologies such as CCTV or keylogging, or simply lobbying government. It can reduce trust (pdf) which depresses growth by making us loath to invest in risky projects, or by worsening the quality of government policy. A low-wage economy can discourage investment in labour-saving technologies.

I was reminded of this this week when working with an existing scenarios produced by the British government in a workshop. The scenarios were well documented and well-modelled, and we were using them for that reason.

But at my table we were working with a scenario that assumed that in a Britain that was highly polarised you could also have steady economic growth. As one of the workshop participants said, very quickly, this isn’t a coherent world: you don’t get stable economic growth if there is high inequality.

Dillow suggests that big wage differences between CEOs and middle managers also encourages target chasing: I can see why that might be bad for growth, but I think the mechanism here is the financialisation of the corporate sector.

Capitalism creates powerful groups with a vested interest in maintaining stagnation

Dillow has an entertaining list of some of these groups:

incumbent companies wanting to restrict competition; financiers wanting the low interest rates that economic stagnation brings; lawyers and accountants wanting a complex tax system that strangles growth; or landlords opposing new building or property taxes.

These no point in doing the hard of work of developing products or services that customers might want to buy if you can lobby governments for tax breaks instead. Dillow quotes an article by the economist Joel Mokyr:

Technological progress encounters resistance from various groups that believe they stand to lose from innovation... Under fairly general conditions, it can be shown that the single economy will move inexorably to an absorbing barrier of technological stagnation.

What struck me about this list is that although the British economy is structurally weak, largely from its over-enthusiastic embrace of privatisation and weak regulation, with a side order of Brexit, this isn’t specific to the UK. These sound like a set of characterised that apply generally to the oligopolistic, over-financialised features of late capitalism.

The other thing you notice is that from the point of view of asset owners, at least three of these five factors are a feature, and not a bug, even though neo-classical economics would say that this shouldn’t be the case.

It brought a couple of things to mind. One was Wolfgang Streeck’s article about the end of capitalism. From 2014:

While we cannot know when and how exactly capitalism will disappear and what will succeed it, what matters is that no force is on hand that could be expected to reverse the three downward trends in economic growth, social equality and financial stability and end their mutual reinforcement.

There’s much more in his article, but this piece is getting too long, so I am just going to list his “five disorders” here: stagnation; rising inequality; the plundering of the public sector; corruption; and lack of a stable global financial centre:

In summary, capitalism, as a social order held together by a promise of boundless collective progress, is in critical condition. Growth is giving way to secular stagnation; what economic progress remains is less and less shared; and confidence in the capitalist money economy is leveraged on a rising mountain of promises that are ever less likely to be kept.

My second observation is—probably no surprise to regular readers—that the base case of Limits to Growth projects declining industrial production in the 2020s. The base case has tracked other outcomes fairly closely over time. So perhaps this is how the capitalist world ends: not with a bang but an endless series of whimpers.

2: History as lessons, history as inspiration

The Five Books site has an interview with the social philosopher Roman Krznaric on how the lessons of history might help us navigate the present. It’s prompted by his recent book History for Tomorrow.

Obviously there’s a long tradition that we can’t learn from history, and there’s another one that says that we tend to draw the wrong conclusions because we use history metaphorically and then choose the wrong metaphors. One of the books in his selection, Why History Matters, by John Tosh, acknowledges this directly:

Tosh writes about... making analogies from history, and how we need to be very careful about doing that... Not every war is another Vietnam, not every dictator is another Hitler and not every financial crisis is like the Great Depression of the 1930s. Let’s not just look for similarities but be well aware of the differences.

In terms of the subject, Tosh’s book seems to be the most interesting here, and Krznaric acknowledges its influence on him:

[An] important thing that John Tosh does is emphasize learning from history in terms of the genealogy of our current crises. When we’re looking at something like the war in Iraq or Afghanistan, we should be trying to figure out: ‘What’s the deep story of how we got here?’ That means going back to the history of Western colonialism in the Middle East, because if we don’t understand those earlier episodes, then we’re going to make very poor decisions today.

This seems like a good point to mention the former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, discussed in the interview. Before the second Iraq war he consulted historians as to whether Britain should get involved in the war:

Tony Blair invited a group of leading academic experts – including historians and political analysts – to come and talk to him about what they thought about Britain joining the US invasion. I think there were six people who went along to 10 Downing Street and basically said to him, ‘Don’t do it – it will be difficult at best and catastrophic at worst.’ And he totally ignored them.

John F. Kennedy, on the other hand, had read Barbara Tuchman’s book on World War 1, The Guns of August, on how misunderstandings and miscommunication led to the outbreak of war, and was determined during the Cuban Missile Crisis that similar mistakes didn’t lead to nuclear war.

Richard Neustadt and Ernest May, who worked for the Kennedy administration, wrote Thinking in Time—referenced here, although it’s not one of the five books—to try to deal with the problem of which metaphors we were extracting from history, developing a process that explored differences as well as similarities.

I wrote about Thinking in Time here, and noted

Neustadt and May offer a warning to guard against the “seductive influence of an analogy.” This does not mean that one shouldn’t use historical analysis; rather, it is a reminder to not use history as ashortcut for analysis.

One of the things that Krznaric cautions about is that instead of focussing on history as a warning, we should also look to it as a source of agency and inspiration. He took this in part from Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States:

In The People’s History of the United States, he writes: ‘Most histories understate revolt, overemphasize statesmanship, and thus encourage impotency among citizens.’

The People’s History may be the biggest selling radical history book in history. Zinn’s essay collection On History is one of his Five Books:

In one [essay], called “Historian as Citizen,” he talks explicitly about the way we need to think about history as full of possibilities for learning for the present, and learning from the inspirational moments, not just the warnings.

In his own book, he started with a set of critical issues facing us today, and then used a series of questions as a kind of filter process:

I asked myself, ‘Okay, so which episodes in history help inform those issues?’ That cuts out a lot of the past. Also, ‘Which of these episodes are about not just warnings, but possibilities for inspirational change, change for the common good?’ Another layer was, ‘Which of these are about change from below as much as possible, not just change from above?’

He also limited himself to the last 1,000 years, because the history gets a bit unreliable before that.

Some of his examples here reminded me of the futurist Jim Dator’s observation that one source of the future is from elements of the past that have become submerged and reappear again. And some of this seems to be about exploring social structures from the past that we might want to understand better for our futures.

(Tribunal de las Aguas, Valencia. Photo: José Jordan, via UNESCO/Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 3.0)

One example, in a world which is experiencing increasing conflicts over water, is the water court in Valencia, the ‘Tribunal de las Aguas’, which has been meeting or hundreds of years:

It’s Europe’s oldest legal institution... There are these eight black-cloaked figures who come out every Thursday at 12 noon and meet outside the west door of the cathedral in Valencia and hold public hearings. They are democratically elected representatives, in charge of the local irrigation canals of the Valencia agricultural hinterland, where we get our juicy Valencia oranges from.

This is one way of managing the commons. He discovered this example in Anarchy in Action—one of his Five Books—by the anarchist writer and theorist Colin Ward, which has many examples of forms of social co-operation.

A darker example is about how the rise of the printing press led to the widespread persecution of women as being ‘witches’, an early form of clickbait. 500 people were killed for witchcraft in Britain between 1530 and 1680, 25,000 in Germany. This is also a story about how people get scapegoated when systems of meaning are changing.

Krznaric is also interested in patterns, which I think is an underlying principle of futures work: patterns exist.

Some of this takes him back to John Tosh. In his own book, Krznaric has a chapter in his book on artificial intelligence, which seems essentially modern.

But reading Why History Matters made me think... Have we ever created large-scale systems which could potentially get out of control, which is one of the potential risks of AI?’

And I reasoned that, yes, we have. We invented the instruments of financial capitalism in the Netherlands in the early 17th century: the first stock exchanges, the first public limited companies, marine insurance. It was a human-created system that very quickly got out of control, with the advent of multiple financial crashes.

As the futurist Wendy Schultz says from time to time: to be a good futurist you also need to be a good historian. Deep structures matter.

j2t#611

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

I hadn’t realised how big the slump was in the 1870s crash, by the way.