23rd May 2021. Infrastructure | Coal

How our utility companies were turned into another investment vehicle // Using theatre to mourn the closure of a coal plant

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: How our utility companies were turned into another investment vehicle

One of the current mysteries of British political economy is that our privatised water companies have promised to spend £10 billion to improve our sewage infrastructure, but that we’re all going to pay for it—while they are still paying billions of pounds to their shareholders.

While trying to understand this mystery, I came across a shortish review of Brett Christophers’ recent book Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Rule the World, by the economist Diane Coyle, that seemed to have much of the answer in it.

(Image: Verso Books)

Over the course of a series of books, Christophers has researched the nature of different forms of rentier capitalism—in Britain and elsewhere. His latest book focuses on the way the infrastructure sector is financed in the post-privatisation era, in Britain and elsewhere.

Britain’s physical infrastructure — water, energy, etc — is largely owned, and opaquely, by asset managers such as Macquarie and Blackstone. There are several features of infrastructure. Typically, it is a “natural monopoly”—there’s no point in having multiple sets of water and sewage pipes connected to a household, for example.

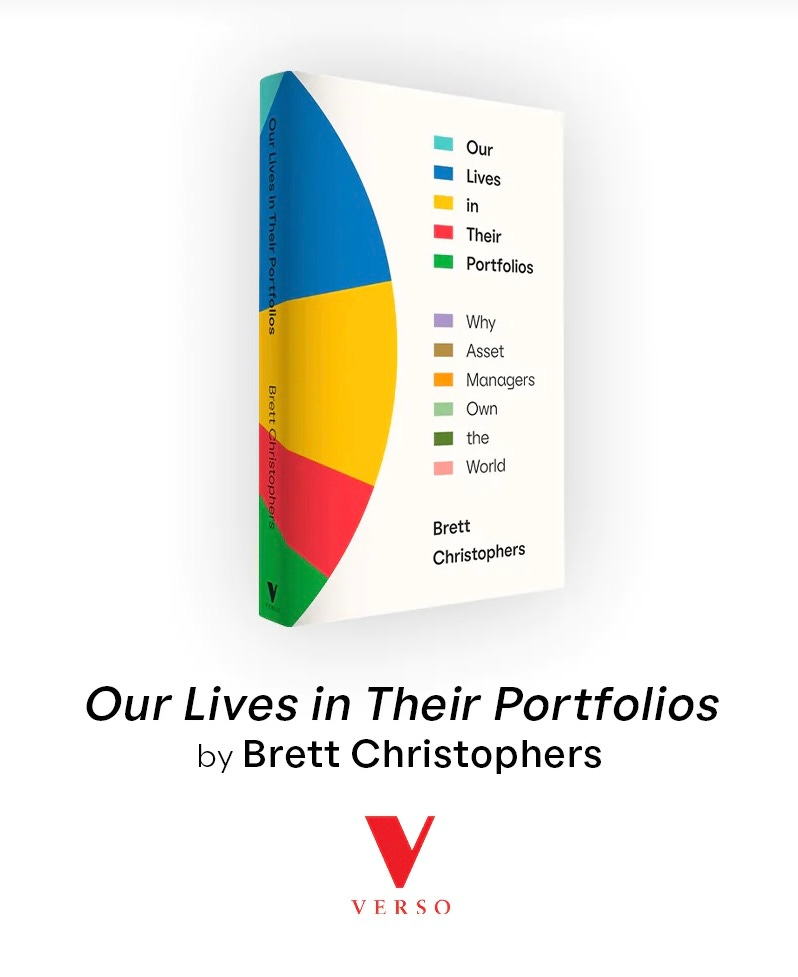

It also is a long-term investment—I was once told by Transport for London that a typical London station might be refurbished every 60 years. Most infrastructure, outside of the road network, comes with steady revenue streams attached. And this means that the investors who like to have infrastructure investments in their portfolio are often investors such as pension funds, which have long-term liabilities. So, when asset managers—which have shorter term horizons—insert themselves here there is a mismatch:

However, while the investors have long term horizons and look for steady returns (such as rents or fee income), and the infrastructure itself is long-lived, the funds set up by the asset managers coming in between are short term – a few years at most.

I thought it might be worth drawing a diagram to spell this out.

(Source: Andrew Curry)

It’s also worth noting a couple of other features here. The asset managers typically commit only a fraction of their own money (e.g. typically 1-5%) to the funds that they manage that actually own the infrastructure assets but the rewards they get for their role here are on a scale somewhere between “disproportionate” and “eye-watering”.

Brett Christophers appeared on the podcast A Long Time in Finance, hosted by Jonathan Ford and Neil Collins to talk about the book (30 minutes), and mentioned that Blacktone’s average salary was $2 million, funded by management fees of 12%. (I had to replay this bit of the recording to check I’d heard it right). It’s also not clear what they’re really doing for their money, as Coyle notes:

As all the operational aspects are contracted out to service companies, the asset managers are neither energy or water companies, nor investors in such companies: they are pure rentiers. The risks are borne entirely by others – and particularly the people experiencing crumbling homes or essential services.

So—if you were drawing this model up from scratch, on a blank piece of paper—you’d say either that this misalignment problem is so severe that you should look for a different model (e.g. public interest companies, as in the case of the Welsh water company Dŵr Cymru), or ensure that regulation is broad enough to remove the obvious moral hazard that is involved (which is the sewage problem in a nutshell).

In fact, certainly in the UK, regulation has been captured by narrow definitions of market competition and consumer harm. On the Long Time in Finance podcast, one of the interviewers reminded me that the water regulator Ofwat had had a decision that reduced returns to investors overturned by the Competition and Markets Authority.

Similarly, they noted the ratchet effect that seemed to apply to the companies’ dealings with regulators—effectively a kind of bluff whereby the owners suggest that if the regulators tighten regulation, the investors will walk away, but so far a bluff that hasn’t been called. This may be naivety or it might because there’s a significant degree of regulatory capture in the way that the regulators behave.

On the podcast, Christophers suggested that the reason we see our infrastructure companies

being ransacked for rent, with maximum income being extracted from them, and minimum cost being undertaken, is because the nature of the asset management model requires that to be the case. So investment funds raise money from funds by promising them higher returns than they are able to get through ... investment in other asset classes, and the way they recruit their investment professionals is by offering them higher salaries and higher bonuses than they will get from McKinsey.

The gap here is that after the asset owners have extracted their share, the returns to the pension funds—and therefore to pensioners—are no higher than they would have been had they invested in other things. The share taken by the asset owners is almost pure extraction.

As Diane Coyle says:

While I don’t have a problem with the idea of private money coming into infrastructure investment, there is a clear incentive issue: as Avner Offer’s excellent recent (2022) book Understanding the Private-Public Divide set out, private money will always require pay-back faster than a major piece of infrastructure can deliver, so there are challenges in structuring the investment and governance. And the lack of transparency and failures of governance over the maintenance and operation of infrastructure and housing, resulting from the financialized structure of the investment through asset managers, are shocking.

One of the frustrating things about both the review and the podcast is that both seemed a bit blank on what to do about this. (This was a bit depressing, since Diane Coyle is one of the best public policy economists in the UK: she hopes that “the first step is clearly the disinfectant of light”, which is about half way down Donella Meadows’ list of places to intervene in the system.

Certainly in the UK, it’s a consequence of the way that privatisation of public utilities was structured—one of those second-order effects that those brainboxes at the Treasury didn’t figure out might happen. (Some soft simulation work to understand how actors might actually behave might have helped).

But the reason that the pension funds go through the asset managers is because they have to: the asset managers are the owners. And the asset managers are the owners because they can squeeze out the type of generous returns that support $2 million average salaries. It’s another example of businesses extracting value to get high returns in an increasingly low return world.

Utility businesses should be dull businesses with steady but unspectacular returns that generate enough money to maintain themselves over time and upgrade as necessary. What we’ve actually got is a sector where returns are set without apparent regard for long-run costs or investment requirements, or social or public need. There are ways to both tighten and redesign regulation to bring these back into line. Change the rules, change the goals: push it higher up Donella Meadows’ list. Call the bluff, in other words.

There’s a short ‘trailer’ interview with Brett Christophers about the book on the Verso Books site (1’11”).

2: Using theatre to mourn the closure of a coal plant

One of the phrases we use when we talk about the Three Horizons model is that it is necessary to be hospice workers for the dying culture (Horizon 1) and a midwives for the new (Horizon 3). The phrase is from the late Californian Senator John Vasconcellos, and it is captured in Graham Leicester’s fine book, Transformative Innovation.

There’s an important point here: that in times of change it is necessary to acknowledge the value of the old even while needing to let it go. In practice it’s hard to do. So it was interesting to read in Inside Climate Newsabout an arts project in the United States to help an Appalachian community mourn the closure of the coal-fired Conesville Power Plant in 2020.

the coal-fired plant that operated for more than half a century will get a proper goodbye in the form of a community theater and art project performed in Coshocton, Ohio. The purpose of the outdoor play, titled “Calling Hours,” is to provide closure for the community and help residents make sense of the varied emotions when a local landmark—a major employer and also a major polluter—reaches the end of its life.

(Conesville Power Plant, 2020. Photo by funksbrother/Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

The plant opened in 1957, and at its peak employed 600 people. But by the time it closed in 2020 it was no longer able to compete with other forms of energy, notably renewables. The play was based on local oral histories and was written by written by Anne Cornell, a longtime local resident and artistic director of the nearby Pomerene Center for the Arts. The play is even-handed in the stories it chooses to tell. On the sense of place, for example:

“You could be up to 30 or 40 miles away at certain points when you saw those stacks,” said a monologue from the perspective of a man in his 80s who was born and raised in Conesville. “Even my 3-year-old great grandson, when he’d see your stacks, he’s like, ‘Oh, that’s home!’ That strikes close. I think that’s what we all look forward to in our daily lives—getting home.”

On the other hand:

it also brought the constant sound of trains delivering coal, and left behind coal ash that used to float through the air and put little holes in clothes hung out to dry. “The company hung buckets in town to collect the ash—’data’ they called it,” the man said about the plant’s early days. “Seems pretty darn primitive now.”

The play included live music and animation, and was performed in the open air:

“When you have a major power plant in your community, a lot of work just happens because they’re there,” (Anne) Cornell said. “They need truckers. They need all sorts of contractors. So it was a big, broad impact on the community as far as jobs and income and a huge tax base” when the plant closed.

The project is part of a bigger project, the Ohio Coal Communities Project, being run by Ohio State university. Faculty, staff and students are doing community case studies. Jeffrey Jacquet, a professor of rural sociology who’s involved in the initiative, said:

“Communities all across the country are grappling with how they transition away from coal,” said Jeffrey Jacquet... How can the arts help tell the story of where these communities have been and help to animate discussions of what comes next?”

Closer in, Anne Cornell points out that these are necessary questions for her own community:

“It’s important to see how everything lines up so that we can talk about how we move forward as a community,” she said. “That’s what you’re supposed to do with a memorial, right?”

j2t#458

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.