29 August 2024. Information | Water #598

The politics of information // Water conflicts are increasing

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The politics of information

There’s a long and fascinating interview at Five Books about the politics of information with the political scientist Henry Farrell. It’s from 2020, but for some reason it popped into my feed recently, and it intersected with some work I’m just starting on.

Five Books originally asked Farrell to choose the best five books on political science, but he told them that this was too broad a topic. Intriguingly, as he started to think about the politics of information he realised that there was a potential university course there.

The five books he chooses are:

Red Plenty, by Francis Spufford

The Market System, by Charles Lindblom

The Sciences of the Artificial, by Herbert Simon

Radical Markets, by Glen Weyl and Eric Posner

Uncanny Valley, by Anna Wiener

I’m not going to work through his discussion of every book here—better for you to read the interview at Five Books for that. But the way the question is sketched out raises a lot of interesting issues:

If we are to understand how politics and markets work at the moment, we need to pay attention to how algorithms work, and how the economy is being remade from the ground up by these new forms of information processing. We don’t know nearly as much as we ought to about the workings of these processes of information gathering, of information analysis, of information use, which leads to a very important new set of questions.

One of the starting points for this examination was an article in the Economist (behind a paywall), by the magazine’s information technology editor, Ludwig Sigele, who suggested that this was already an inter-disciplinary question, but that the various disciplines weren’t talking to each other:

‘We’ve got a bunch of people thinking about this in economics, in political science, in computational sciences, in statistical physics: how do we pull this together?’

(Catalogue for the 1970 MoMA exhibtion ‘Information’. Kynaston McShine. Fair use.)

Farrell sees this as being important because it is, in effect, a future facing question about the shape of our political institutions. Because our political systems are still shaped by the last generation of informational institutions:

The political systems that we have... were built for an era where information was extraordinarily important, but where the capacities to process and disseminate information were very, very limited. We used to live in a world where if you wanted to get information out to a large number people you effectively had to buy a printing press, or own a newspaper or television station.

Of course, it doesn’t work that way any more:

Now we find ourselves in a different world, in which the scarce resource is not the capacity to publish, but the capacity to pay attention. One of the crucial questions we need to understand is how this world of information surfeit, of information overload, is stressing and straining our political system.

I think that we can also usefully turn around the framing of this. As new systems emerge they configure around abundance, as Bill Sharpe argues in his book on the Three Horizons model. The abundance here is that the cost of information processing and distribution has meant that both of these things are now radically abundant, and not always in good ways.

One of the themes that runs across this discussion is the notion that as large learning models, and by extension forms of artificial intelligence, become more sophisticated, then these will become better planning tools than leaving this to market-based price signals:

[W]e have people in Communist China, like Jack Ma, suggesting that we may not need markets anymore; we may be at the point where planning is actually going to work because we’ve got machine learning. Machine learning is going to provide us with the sophisticated means to achieve what the planners were trying to achieve and where they failed.

And this feeds into one of then deep underlying anxieties of our time, at least if you are sitting in large chunks of the Global North: that authoritarian capitalism will out-compete democracies because it is better at directing technologies. For example:

There was a piece by Yuval Harari in the Atlantic about a year-and-a-half ago, saying that authoritarian capitalism is going to beat democracy because authoritarian countries like China are able to use all of these new technologies to run the economy far more efficiently and keep an eye on everyone.

Farrell marshals a number of people who are sceptical about this. He’s a sceptic himself, because these technical systems start misbehaving as soon as people get involved in them, and as soon as they start interacting with systems of power.

For authoritarian countries, China in particular, you have these feedback loops between the categories that people are using to try and understand the world in the central committees, and the actual world they are trying to explain. We know how politics work in these systems. Very often, if you’re not implementing the thought of the beloved chairman, your superiors will decide that there’s something wrong with you.

Or, as he quotes the technologist Maciej Ceglowski, machine learning is a form of “money laundering for bias.” Farrell also quotes a piece by the statistical phycisist Cosma Shalizi, who explores the maths that sit behind the world of Red Plenty, which is a novel that explores the Soviet planned economy in the late ‘50s, at a time when many in the West thought the Soviets could have found a system that out-competed the West:

He goes into the math of Red Plenty and explains why it is, given what we understand about computational complexity, that this stuff simply doesn’t work... even if you could somehow get the math to work, the ways in which human beings are likely to respond to these systems invariably mean that they’re going to screw up.

One of the reasons that Red Plenty is something of a cult novel these days is because it explores these conflicts in practice. Farrell sees similarities between the Soviet planners and Silicon Valley:

[T]here’s also a fundamental similarity between the optimism expressed by these young, excitable Soviet economists and central planners back in the 1950s and the optimism of Silicon Valley people today: that software is going to eat the world, and that this is a really good thing.

This notion of abundance seems to sit beneath Charles Lindblom’s book The Market, which is a work of comparative analysis rather than advocacy. Lindblom talks about markets as organising principles for society that enable co-operation, through the institutions that they generate:

[T]he implicit story behind Lindblom’s project is how markets provide this extraordinary means of information processing (as Hayek and others pointed out). Lindblom has a line about how a market system is a system of social coordination by mutual adjustment among participants without a central coordinator.

In the interview, Farrell doesn’t quite get to an answer about the political institutions—we might need to wait for his course for that—although in Radical Markets Weyl and Posner conjure up some radical thought experiments. Closer to home, he points out that Ireland, where he is originally from, has managed to take some radical political steps in the last few years by using new political institutions like the citizen’s convention, and trusting their outcomes. It’s striking that these are forms of qualitative assessment rather than algorithmic systems, although he doesn’t make this point.

He finishes the interview by pointing to work being done by his colleague Marion Fourcade, whose work certainly looks worth exploring.

Her idea is that you can think about all this as classifications and categories and feedback loops. Machine learning processes involve feedback loops where they are supposed to optimize on something and they throw out stuff, based on their classifications of the situations that they’re dealing with... But we also have the actual feedback loops of people’s lives, of the way people use these systems in all of these unexpected ways.

So far, many of these unexpected ways have been—on my reading—about translating the dynamics of broadcasting into a world where information processing and distribution are all but free. That is, after all, what ‘misinformation’ and ‘disinformation’ are about.

The new questions are about translating us from users and consumers of these systems, where we are mostly the product, to ways in which we can participate in shaping them, not as individuals but collectively. But this also reminded me of Dan Davies’ recent book The Unaccountability Machine, because I was looking at my notes over the weekend. (Farrell wrote about this at his newsletter.) Because a lot of that book—which sets out to rehabilitate Stafford Beer’s work on cybernetics as organisational decision-making systems—is about the design of feedback in such as a way that organisations can hear it.

2: Water conflicts are increasing

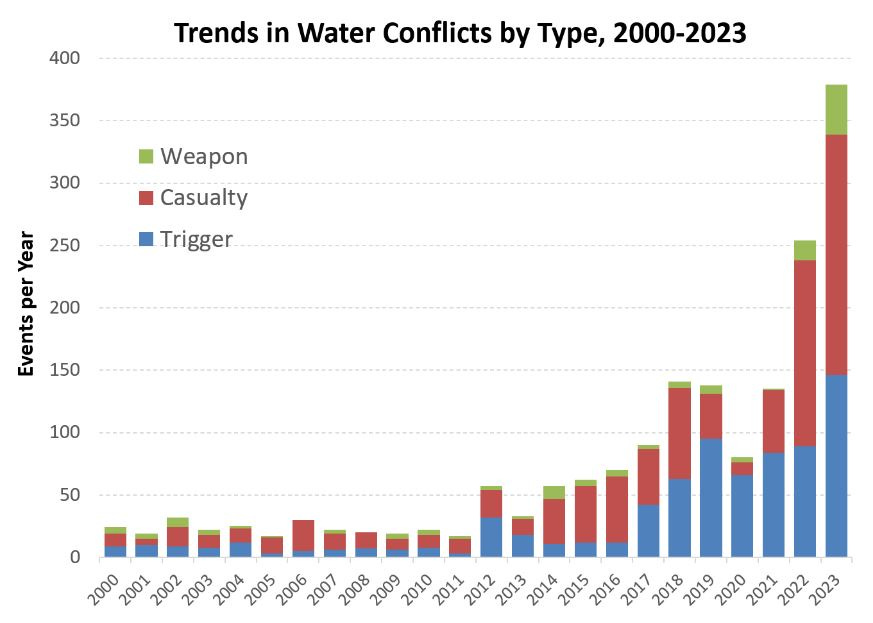

The Pacific Institute describes itself as a “global water think tank”, and one of the things it monitors is conflict over water resources. Its latest report, released a few days ago, shows that there was a substantial increase in the number of conflicts in water in 2023. It’s been trending up over the past few years, and shows a 50% increase year on year.

(Source: The Pacific Institute)

The Institute’s factsheet spells out the main points:

A major jump in violence over water between Israel and Palestine, especially with persistent attacks by Israel on water systems in the West Bank and Gaza;

A large increase in events in India and Latin America associated with drought and disputes over control and access to water; and

Continued expansion of violence over access to water and land between clans, pastoralists, farmers, and herders in Sub-Saharan Africa.

It’s also worth noting that the majority of these conflicts are intra-stateconflicts (62%) rather than inter-state conflicts (38%).

It’s probably worth explaining the basis of this data. The Pacific Institute has maintained a ‘Water Conflict Chronology’ since the 1980s which records events associated with water. The events are recorded in a table and a map.

They publish the criteria for including events in the chronology in the website.

Items are included when there is violence (injuries or deaths) or threats of violence (including verbal threats, military maneuvers, and shows of force). We do not include instances of unintentional or incidental adverse impacts on populations or communities that occur associated with water management decisions, such as populations displaced by dam construction or impacts of extreme events such as flooding or droughts.

They updated this definition in 2018, and removed some events from the Chronology as a result.

The Pacific Institute classifies these events in three ways: trigger, weapon, or casualty. A trigger is where water is a

“root cause of conflict, or underlying cause of ongoing tension that is contributing to conflict, where there is a dispute over the control of water or water systems”.

Weapon is like it says on the tin:

“where water resources, or water systems themselves, are used as a tool or weapon in a violent conflict.”

Casualty describes events where

”[w]ater resources or water systems as a casualty of conflict, where water resources, or water systems, are intentional or incidental casualties or targets of violence.

The Institute breaks down the events in the Chronology by type:

(Source: The Pacific Institute)

The reasons for the increase in water conflict are complicated, but—given how central water is to human societies—it reflects all of the pressures they are experiencing, such as climate change and changes in population. It also reflects the fact that 2023 was marked by the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

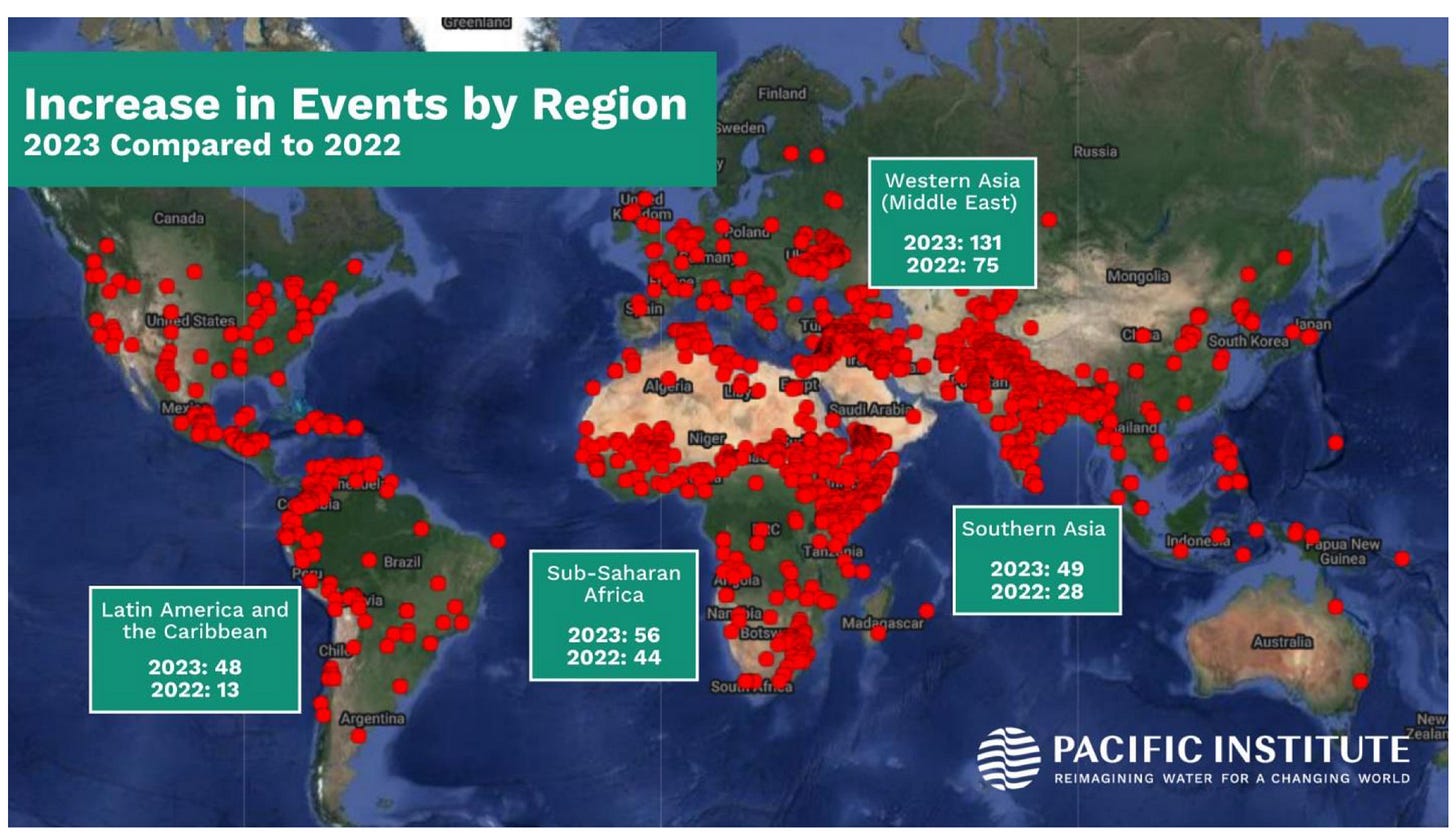

When you look at the regional data, three or four areas stand out: the Middle East (coded in the data as Western Asia), sub-Saharan Africa, and southern Asia.

(Source: The Pacific Institute)

It’s worth noting some of the examples from the database.

In the Ukraine war, for example:

The massive Kakhovka Dam on the Dnipro River is destroyed on June 6, 2023, presumably by Russian occupying forces, causing massive flooding, more than 50 deaths, and ecological devastation downstream, and cutting off water supply for cities, power plants, and irrigation systems.

In the West Bank, even before the war:

Widespread and repeated attacks are reported throughout 2023 on West Bank Palestinian water systems, irrigation, and agricultural land by Israeli settlers and military. These attacks expand after the October attack on Israel by Hamas.

In South Africa:

In February 2023, residents in Gauteng, South Africa barricade roads with burning tires, rocks, and debris to protest water and electricity shortages and one man is fatally shot.

In May, three protestors demanding water supply clash with local authorities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and are shot and hospitalized.

In Central America:

In September, borders between Haiti and the Dominican Republic are closed and military are deployed, in a dispute between the two countries over a Haitian canal project on the Massacre River.

And in France:

In late March 2023, as many as 200 protesters and 50 police officers sustain injuries in a battle in Sainte-Soline, France to stop the construction of giant water "basins" to irrigate crops. Protesters throw projectiles including improvised explosives; police respond with tear gas, water cannons, and rubber bullets.

In other words,water incidents come in multiple shapes and sizes. But this is not inevitable: good governance can reduce conflicts. The Pacific Institute also works in this area.

They note that there are success stories as well:

[P]olicies can be enacted to more equitably distribute and share water among stakeholders and technology can help to more efficiently use what water is available. Agreements over water sharing and joint management of water can be negotiated to resolve transboundary conflicts, such as those along the Tigris/Euphrates rivers, the Helmand River, and elsewhere. When enforced, international laws of war that protect civilian infrastructure like dams, pipelines, and water-treatment plants can provide essential protections that uphold the basic human right to water.

The Institute’s report on this can be found here.

j2t#598

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.