11 May 2025. Copyright | Populism

AI, copyright, and the music business // Dealing with populism involves caring about the local. [J2t #639]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: AI, copyright, and the music business

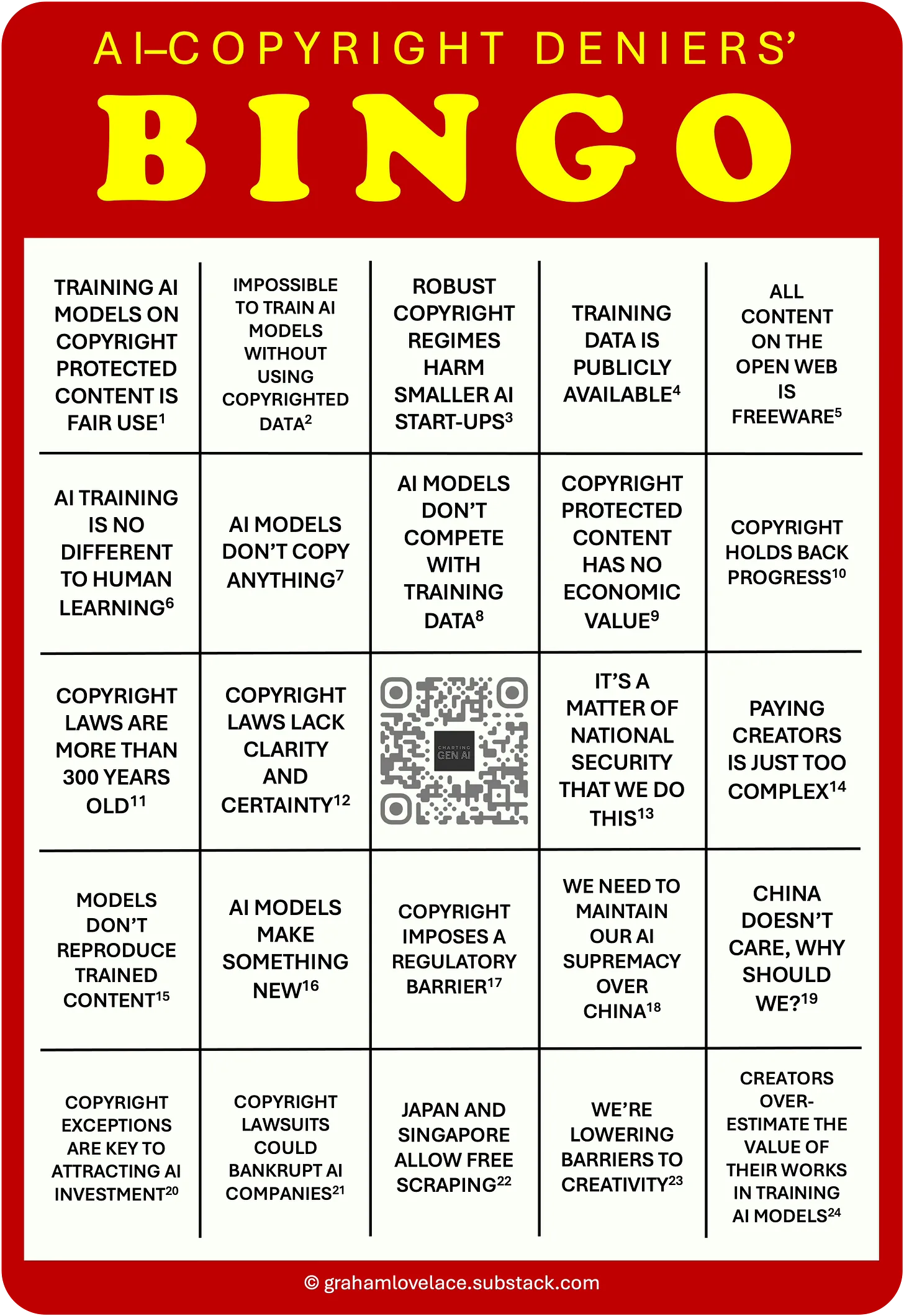

Graham Lovelace writes about media and AI on his newsletter, and he had a memorable graphic recently summing up the claims that Big Tech companies had made about both content and copyright in their attempts to ignore copyright law as they sought to train their Large Learning Model.

Memorable because it took the form of a bingo card.

(Source: Charting Gen AI/ Graham Lovelace)

There are 24 statements on here from tech companies or tech executives on why copyright is, in effect, for the little people (to borrow Leona Helmsley’s famous phrase).

And the rest of the post is the footnotes that substantiate the bingo card entry.

For example, #1, in the top left, is #1 for a reason:

The most frequently cited excuse, used by all the copyright-denying AI companies and stated with such confidence you’d think that fair use — an exception under the US Copyright Act — is settled. Which, of course, it isn’t … as these lawsuits currently working their way through the courts testify.

And you have to admire the chutzpah of some of the others. #2, for example, might be a fact, but it’s not a reason. #4, courtesy of OpenAI, seems to confuse “availability” with the right to access and use content for other purposes:

Just because something is available doesn’t mean it’s legal to take it, as filmmaker Justine Bateman said in October 2024.

Some of it is straight out of the Silicon Valley entitlement playbook. #10, for example, courtesy of Google.

And some of it suggests a certain amount of corporate capture of policy-making processes by AI companies who have persuaded, notably, the British government, that AI is the key to future economic success: #13 has the fingerprints of the famously compliant Tony Blair Institute on it (and who could have guessed):

An assertion made by OpenAI (‘national security’ was mentioned 21 times in its submission to the US AI Action Plan, March 2025), and by the Tony Blair Institute which warned “strict” copyright laws would weaken the UK’s “capacity to protect national-security interests”.

Well, money talks and bullshit walks.

I liked this as a piece of design because I definitely wouldn’t have read a piece that set out, say, “24 myths about copyright peddled by AI companies”. This is more accessible.

You’ll guess from the tenor of Lovelace’s commentary that he’s on the side of the creative industries here, and at the end of the post he also includes a little “cut out and keep” definition of a copyright denier:

1 A person who refuses to accept that copyright exists, or argues it is no longer a valid legal construct.

2 A person who does not want someone to exercise their intellectual property rights, or seeks to remove them.

This is all very well as far as it goes, and I am in favour of formulations of copyright law that ensure that creators get a fair return on their work.

But the creative industries are not angels here either. One of the things that popped into my feed a few weeks ago was a long, long Rolling Stone profile of the Internet Archive, run by Brewster Kahle, which is being sued by the big record companies and the Recording Industry Association of America [RIAA] for $621 million for maintaining an archive of digitised 78rpm records from the 1920s and 1930s.

It’s a complicated case, in one way, and an uncomplicated case in another.

Complicated, in that in some cases the descendants of the performers are on the side of the record companies, and Brewster Kahle doesn’t go out of his way to be lovable. Uncomplicated, in that the Internet Archive acts as an archive for historic things that their nominal owners can’t be bothered to preserve or make accessible.

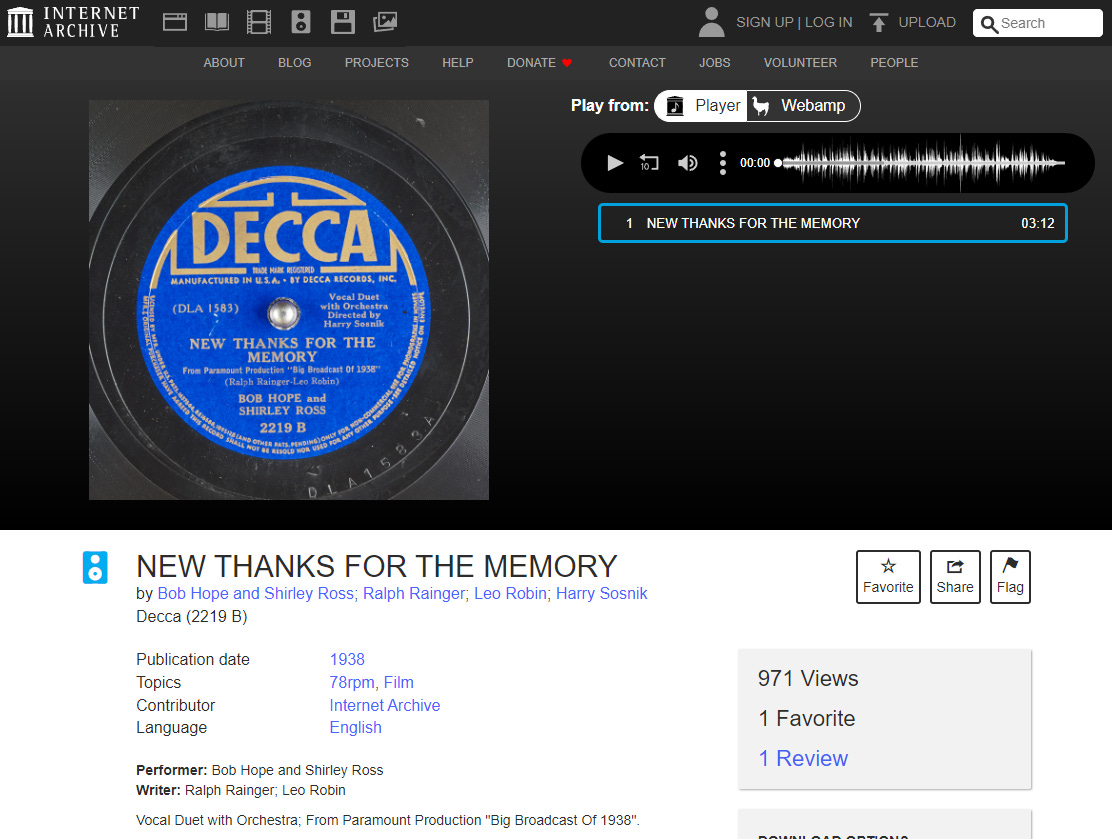

At Techdirt, Mike Masnick explained the Great 78 project that is at the heart of the legal case:

If you’ve ever gone through the Great 78 project, you know quite well that it is, in no way, a substitute for music streaming services like Spotify or Apple Music. You get a static page in which you (1) see a photograph of the original 78 label, (2) get some information on that recording, and (3) are able to listen to and download just that song.

Also, when you listen to it, you can clearly hear that this was digitized straight off of the 78 itself, including all the crackle and hissing of the record. It is nothing like the carefully remastered versions you hear on music streaming services.

(The Internet Archive Great 78 project. Image Michael Masnick/ Techdirt)

This last point is important, I’d say, because the record companies’ case, at least in part, is that the existence on the Internet Archive of the original 78s of recordings that they have later cleaned up and reissued—some 4,000 among a total of 400,000–somehow has an meaningful economic cost to them.

Kahle’s view of the Internet Archive, as he explains to the Rolling Stone writer Jon Blisten, is this:

“It’s a research library. It’s there to record and make available an accurate version of the past,” Kahle says. “Otherwise, we’ll end up with a George Orwell world where the past can be manipulated and erased.”

As Blisten says, “this work has long rankled one of the most powerful forces in the United States — rights holders — and the threat of copyright lawsuits has always loomed over the Archive.”

And the case of the Great 78 project spells out how this works (again from Rolling Stone):

The Great 78 Project bills itself as a “community project for the preservation, research and discovery of 78 rpm records”; the labels, in their lawsuit, call it an “illegal record store.” They claim the availability of these digitized 78s constitutes “wholesale theft of generations of music,” with “preservation and research” used as a “smokescreen.”

I don’t have space to go into the detail of the project here, but when you read Jon Blisten’s account of the work of the Internet Archive in building this library, it involves impeccable care and curation, notably by the archivist George Blood:

Blood, who is also named as a defendant in the lawsuit, calls this “preservation of the cultural record” one of the “great accomplishments” of the Great 78 Project. “Probably 95 percent or more of this content is not available anywhere,” he tells Rolling Stone.“Whether they were small labels, or obscure pressings, they have been lost to time.”

And the RIAA declined Blisten’s requests for an interview, which is always a ‘tell’ in these cases.

US book publishers have similarly gone out of their way to use the law to kill off the Internet Archive’s Open Library project.

If you want to preserve culture, in short, record companies, publishers, and film studios are terrible at it. They have no incentive to do it. It’s not part of their business model—in fact, it runs completely contrary to it.

I was struck by this earlier this week while writing a profile of the influential Irish band Moving Hearts for the Salut! Live folk music blog. Their first two records, Moving Hearts and Dark End of the Street, released in 1981 and 1982, were both electrifying good, but neither is in print anymore, either as a physical artefact or in digital editions. WEA, which released them, can’t be bothered.

I don’t want to be misunderstood here. If Large Language Models can’t be trained without breaching copyright, or paying for it, that’s further evidence for me that the business models of the companies promoting AI are fatally flawed (a cursory look at their investment costs and the likely returns will also tell you this.)

But that doesn’t mean that any of us should be happy about the way that media companies use copyright law as an instrument of cultural and economic control. Copyright was intended to strike a balance between protecting and rewarding authors (later extended to other creative producers as the age of mechanical reproduction arrived) and ensuring a rich intellectual commons. It wasn’t intended for large corporations to wreck the commons, as the big record companies and the Recording Industry Association of America are intent on doing to the Internet Archive.

2: Dealing with populism involves caring about the local

Watching both the British Labour Party and the American Democrats floundering in the face of hard-right populism, and before them the German coalition, made me think a bit more about the roots of populist politics.

In the UK the hard-right Reform party won a number of councils across England in recent local elections, and also gained a seat from Labour in a by-election.

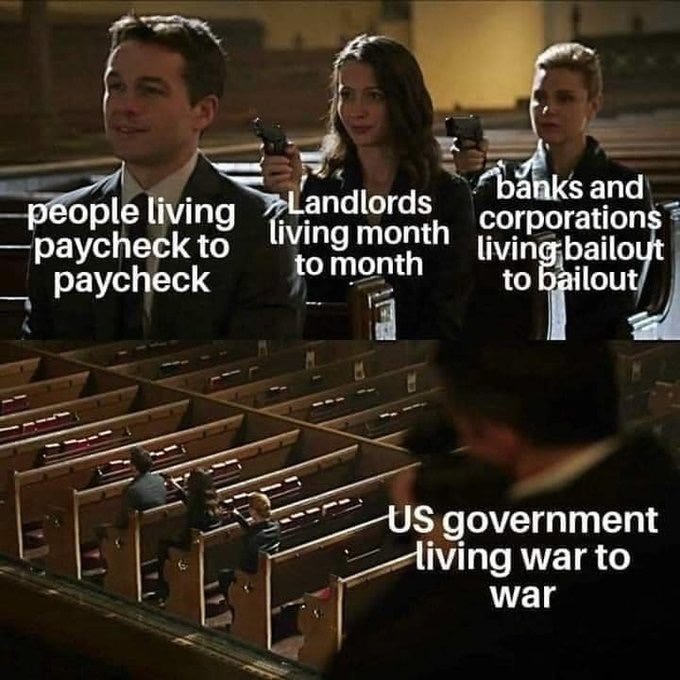

The current populist surge—everywhere—goes back to the 2008 financial crisis, and that created two dynamics that played out in a way that reinforced each other.

At its heart, a vote for a populist party is a response to ontological insecurity, the sense that your life is no longer on a secure footing. (I know: ‘ontological’ is one of those words, but it describes how you experience being in the world.) This feeling of dislocation is important, but it’s not all of the story.

The second part is a sense that the system is rigged against you: whoever you vote for, the government will get in—and that the government doesn’t care about this.

In the wake of the financial crisis, for example, the British banks were bailed out without any conditions being imposed on them about their social or public contribution to society. And the method by which they were bailed out—quantitative easing—mostly inflated the value of assets, so making the rich richer, and more specifically, increasing the cost of land and making housing in particular less affordable. (This effect was seen well beyond the UK and the United States: almost everywhere where there was a housing market, in practice.)

(Source: Finance memes, via Twitter)

Or: In the UK, the inability of the water regulator to do anything about the privately owned and hyper-financialised water companies while they were literally pouring shit into the rivers and coastal waters was one of the emblematic failures of the last Conservative government (and for the last year, of the new Labour government as well.)

Populist parties takes this feeling of unease, of not having a firm footing in the world, and they blame it on migrants and refugees, and sometimes, but not always, on corporate interests as well. This kind of labelling short-circuits the more complex causes that actually sit behind these systemic effects, but they are symptoms, not effects, noise, not signal.

We actually know quite a lot about what drives support for populist parties, from research across Europe. Political scientists have done credible research, even if most of that hasn’t trickled through to the “political strategists” who work for political parties.

I have written about some of this here before, but it’s worth repeating. Research in Sweden and in Germany says that the biggest signal of populism is local emigration, with loss of jobs, services, and local status that goes with it.

Populist voters are also more likely to disagree with the statement that “my children will have a better life than me”, although it’s going to be hard for anyone to agree with that if climate change keeps accelerating.

In England, it’s too soon to analyse the recent local election results. Likely caveats include: the apparent collapse of the Conservative party, which may may now be terminal, and the older age profile of local election voters, antagonised by gestural Labour Party decisions such as removing benefits from them such as the Winter Fuel Allowance.

But essentially, populism is a local phenomenon. It’s about a sense that your place no longer feels like it has worth, that it’s going downhill.

The responses to this from centre-left politicians come in two main kinds. The first is to suggest that the government should do more of what Reform is doing: being even tougher on immigration, even withdrawing from the European Court of Human Rights.

This may just tell us that they are not very good at politics, of course. You can’t outflank a hard right party on immigration. Even if you could, immigration is necessary to have a functioning economy (and a functioning higher education sector) in the UK.

And even the palest of social democratic parties need to believe in rights, because rights underpin their entire raison d’etre. The clue is in the words ‘social’ and ‘democratic’. Despite this, details haven’t stopped the ‘Blue Labour’ faction within the Labour party from being quite influential at the moment. ‘Blue Labour’ believes, broadly, in combining left-wing economics with right-wing social policies: anti-immigration, tough on crime, anti DEI.

The second is a version of what Starmer and Reeves have been banging on about since they took office: growth, growth, growth. It’s not particularly thought through, but what it’s meant to do is to increase productivity, which is a route to increasing living standards and the tax base.

This has been theorised better by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in their book Abundance, which I need to come back to here on another day, but in essence it’s a version of a ‘green new deal’, facilitated by forms of deregulation to enable infrastructure delivery. Here’s a summary in Vox:

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson catalog American liberalism’s failures to deliver material plenty — the housing shortages that plague blue cities, the green infrastructure that congressional Democrats funded but then failed to actually build, the high-speed rail system that California promised but never delivered...

Their “abundance agenda” is

a series of regulatory reforms and public investment programs aimed at facilitating higher rates of housing development, infrastructure construction, and technological progress.

Most of their critics are on the progressive left. Broadly, the critics’ argument—as Henry Farrell suggests—is that

building a future also involves building a political economy of interests that will make the vision possible, and sustainable over time.

In other words, it involves politics.

(The performative politics of Heathrow. Photo: Mike McBey/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

You can see some of the same problems in the British government’s approach to the same set of issues. Signalling that you’re in favour of a third runway at Heathrow despite most of the policy evidence is performative nonsense that benefits only the owners of the airport, even leaving aside the emissions issues. Fixing housing would be a good idea, but you can’t do that quickly just by building, much as Britain’s biggest housebuilders would appreciate it.

So if populism is about people feeling insecure in their localities, what does a progressive politics of localism look like? The obvious answers start with places.

Supporting community wealth building initiatives which keep money in towns and cities is one place to start: the so called Preston model, using anchor institutions such as universities and hospitals to support local procurement, to stop money being sucked out of communities.1 Another is protecting community assets so they aren’t bought by property developers—although that might involve doing something about land values.2 Or even: just ensuring that local authorities have enough money to maintain the quality of their local areas.

Some of these require spending, but some of them don’t. I could add to this list. Reforming housing law to protect tenants properly costs no money, but requires political will. As I wrote recently here, the Bank of England could cancel all the debt in the secondary/distressed debt market every year for a fraction of the money that it sends in interest payments to the British retail banks, taking pressure off a lot of poor households.3 Or it could use those interest payments as leverage to ensure that local financial institutions exist in smaller towns and in peripheral areas. Or it could do both of these things.

But to spell this out: if social democratic parties want to head off hard right populism, they need to focus on economic justice.

It’s also worth noting that politically it may be worth seeing how Reform go about running their councils. The first thing one new Reform mayor did was to propose further local authority cuts, which will not improve anyone’s ontological security.

But more generally, national politicians aren’t very good about thinking about place. In Britain, way over-centralised, with the dead hand of the Treasury on the controls, they also don’t trust communities to represent their own interests. And on both sides of the Atlantic, politicians seemed to have lost the knack of using political economy to build a coalition that believes in a future. All those years of neoliberalism have really sapped the soul.

j2t#639

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

This is another reason why governments should be more sensitive to the economic health of the higher education sector. As Chris Dillow noted recently on Stumbling and Mumbling, “Our comparative advantage now lies less in manufacturing than in higher education and creative industries: we have (or have had) far more world-class universities than manufacturing businesses.”.

The ways in which land and housing markets have been skewed to benefit landowners and developers are eyeraising, as Nick Bano and Beth Stratford explained on the Verso podcast—a reminder that there’s no such thing as a ‘free market’

There’s lots of detail about all of this in my recent series here on debt. But in summary the UK spends twice as much, as a share of GDP, as either the EU or the USA in making interest payments to banks on the reserves that the banks are obliged to hold with their central banks as a condition of doing business.