X July 2025. AI | Mobiles

AI might be the end of the digital wave—not the next big thing // Banning phones in schools [J2T #645]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: AI might be the end of the digital wave—not the next big thing

Just by way of a thought experiment: what if the current surge in the bunch of technologies that goes under the label of ‘AI’ isn’t the beginning of a whole new technology surge, but is actually the final stage of the digital surge that started in the 1970s and accelerated at the turn of the century?

I’ve been wondering this for a while in a vague kind of a way because I haven’t been able to see the business model that supports the huge investment in AI in the USA. (I’ve written about this before on here.)

This is a long way in to couple of pieces by Nicolas Colin, the strategy and innovation blogger, who has been wondering the same thing, but a lot more coherently. He calls this ‘late cycle investment theory’.

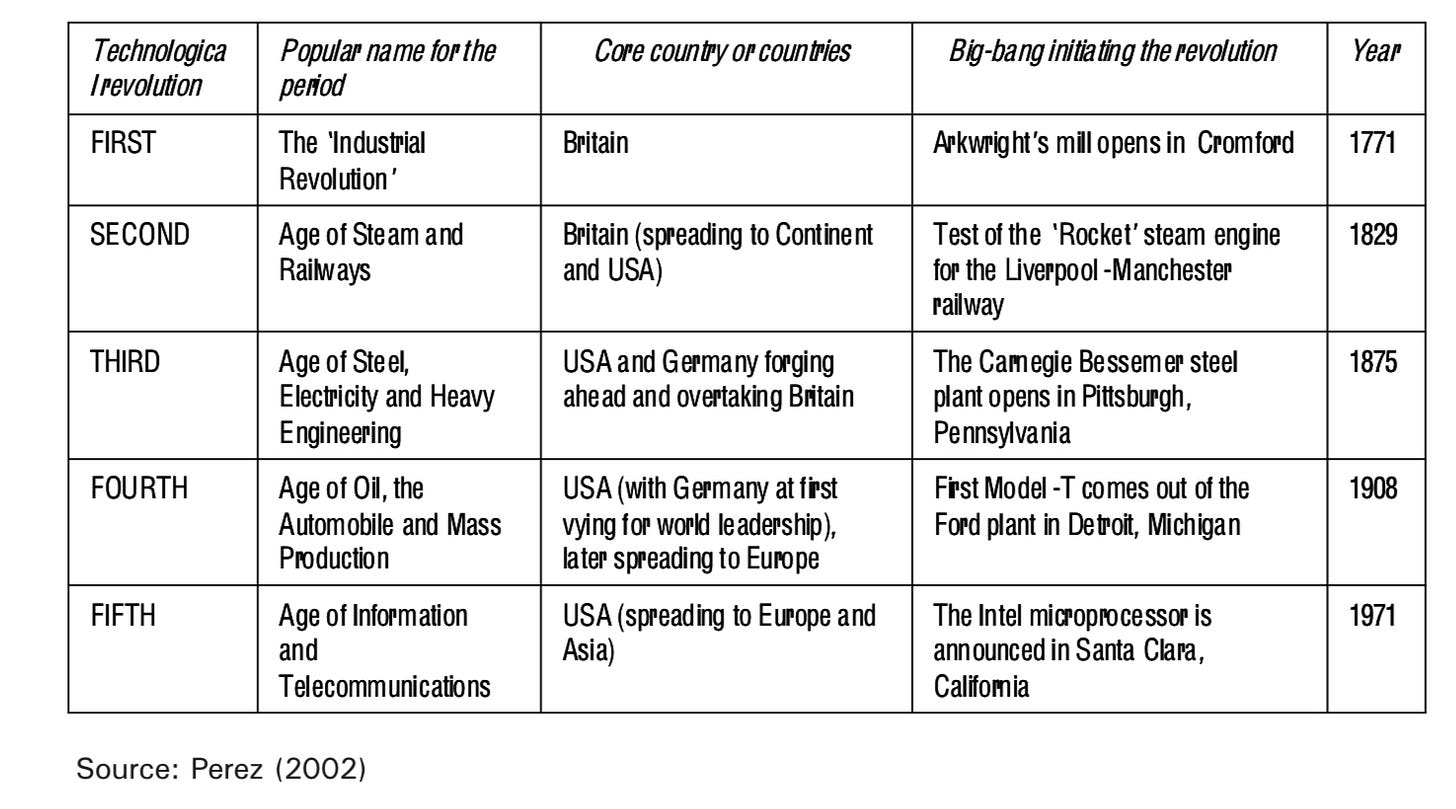

Like me, he is a fan of the work of the academic Carlota Perez, who built on the work of Christopher Freeman to develop a model of how technology and finance interacted to create new long surges of investment, starting with canals and cotton, that run for 50-60 years. (She calls them surges because unlike ‘waves’ each technology embeds itself in the society and its infrastructure.)

The two most recent surges are a cars/oil surge, which started in 1908, and the Information and Communications Technology, which started in 1971.

(Source: Perez)

I’m not going into all of the theory of the Perez model here—it’s online if you want to do that, and I have written about it elsewhere—but the relevant point for the present discussion is that it follows an S-curve, and the first half is slow going, as new infrastructure is ‘installed’, and some of it is below the radar. The internet was a closed academic network for most of the first part of its S-curve.

Halfway through, after a lot of infrastructure has been built out, and usually following a financial crash in which some of the investors in that infrastructure lose their shirts, ‘deployment’ companies take over, with actual customers and business models, and have an accelerated period of growth, before they hit market limits and turn into ordinary businesses. And the investors who have made large returns from that period of growth start looking elsewhere—for the technologies that will make the next surge.

The reason I like Perez’s version is that her model has had a lot of explanatory power over 25 years in terms of watching the evolution of the tech sector.

That’s a long way into Colin’s argument, and let me quote from his first article directly:

Seen through a late-cycle lens, today's markets show signs that we've entered the maturity phase of the computing and networks revolution. The theory, therefore, leads to specific, testable predictions about where capital should go and which strategies will outperform.

He points to three indicators from the tech sector that support this observation that we’re in the ‘late cycle’:

The startup funding collapse of 2022 wasn't just a correction—it may be structural. As investor Jerry Neumann argued in his landmark Productive Uncertainty, startups rely on uncertainty as a competitive edge. When good ideas become obvious to everyone—including well-funded incumbents—the startup model faces real strain.

Then came AI, revealing new dynamics. ChatGPT's breakthrough didn't come from a garage startup but from OpenAI, backed by Microsoft's vast computing power. Google, Meta, and Amazon responded with billions. This pattern—big tech deploying huge capital against well-understood problems—fits the late-cycle theory exactly.

Most tellingly, platform saturation now looks almost complete. Digital transformation has reached most sectors where computing and networks can plausibly work. What remains—healthcare delivery, education, construction, government services—may reflect the paradigm's natural limits, not untapped markets. [His emphasis]

In the second article —some behind a paywall—he looks specifically at the way AI is being deployed, and I’m going to quote/paraphrase quickly the visible bits of this here.

Late-cycle investment theory suggests AI is the efficiency breakthrough of the computing and networks era, not the start of a new one. Just as lean production refined mass production in the 1970s without replacing it, AI optimises the existing paradigm rather than creating a new one.

(Data centre. Photo by penguincakes/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Colin’s done a lot of analysis here, and he’s assembled quite a lot of evidence which he shares. I’m not going to spend a lot of time on this, because I’m more interested in the bigger strategic questions that get raised if he is right.

But it’s worth summarising some of the observations. First, that at the start of a new technology surge, you don’t know it’s happening. You understand the decisive moment afterwards, the moment at which an innovation transformed the cost structure (the Spinning Jenny, Watt’s condensing engine, the Ford production line, the microprocessor). But with AI, the moment was very visible, to the point of being choreographed.

Second, the amount of capital investment is off the scale. At the early stage of a surge, investment tends to be patchy and not fully understood—the sector exists but it is not completely legible yet.

And third, Colin suggests that AI allows computing to reach sectors that have in some ways resisted it:

Like lean production, which extended mass production's dominance for decades through efficiency gains, AI doesn't mark computing's end but its maturation. The technology spreads to previously untouchable sectors, creating the illusion of radical novelty whilst actually representing computing and networks' final conquest of the physical economy.

It’s worth pausing here. Although Perez dates the end of each of her surges from the date of the innovation that makes the next surge, possible, there’s a kind of ‘late deployment’ stage in the old surge while the new one is still in its early stages of development.

Late deployment: So although the ICT surge dates from 1971, much of the final innovation in the cars/oil surge also dates from then. In the UK at that time, there’s still a huge roadbuilding programme of motorways and ring-roads, and these then made possible the emergence of long-distance logistics, big-box out of town retailing, and edge of town business parks. Colin’s arguing that AI is the equivalent of bigger roads and big box retail—different, but more about embedding the technology more deeply than the kind of transformational change that eventually causes a new and distinctive form of abundance.

There’s also social pushback—in the UK the campaigns against big ringroad schemes started in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And perhaps we’re seeing some of that about AI. People seem to hate Google’s inserting of AI tools into its search results, and hate even more that it is all but impossible to turn it off. This doesn’t speak to an exciting technology that is being embraced by its users. A note by Ted Gioia on his music blog says that:

Most people won’t pay for AI voluntarily—just 8% according to a recent survey. So [tech companies] need to bundle it with some other essential product.

This matters for a couple of reasons. In the first place, late stage post-deployment technologies do produce returns on investment, but they’re normal returns, not increasing returns.

But in the second place it sheds a different light on what amounts to a ‘business model war’ going on between China and the United States at the moment through their different approaches to AI.

I think we know plenty about the American model. It is fuelled by a transhumanist ideology that is just this side of The Rapture, as Sam Altman of OpenAI reminds people every week of the year.

As the Exponential View newsletter explained on Sunday, quoting the policy organisation RAND, the Chinese model is completely different:

In Washington, the AI policy discourse is sometimes framed as a ‘race to AGI.’ In contrast, in Beijing, the AI discourse is less abstract and focuses on economic and industrial applications that can support Beijing’s overall economic objectives.

Azeem Azhar of EV added some gloss:

Chinese teams... publish leaner open-source architectures and partner with specialists in areas such as healthcare analytics (Yidu Tech) and adaptive learning (Squirrel AI).

This is partly driven by constraints: China has far less computing power than the US, and needs to build lean. This also means that its model is far more exportable. But the important point here is that if AI is a late-stage technology and not the next large surge of innovation, the Chinese model matches the moment. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised: unlike most countries, a third of the full members of China’s Central Committee are technocrats.

2: Banning phones in schools

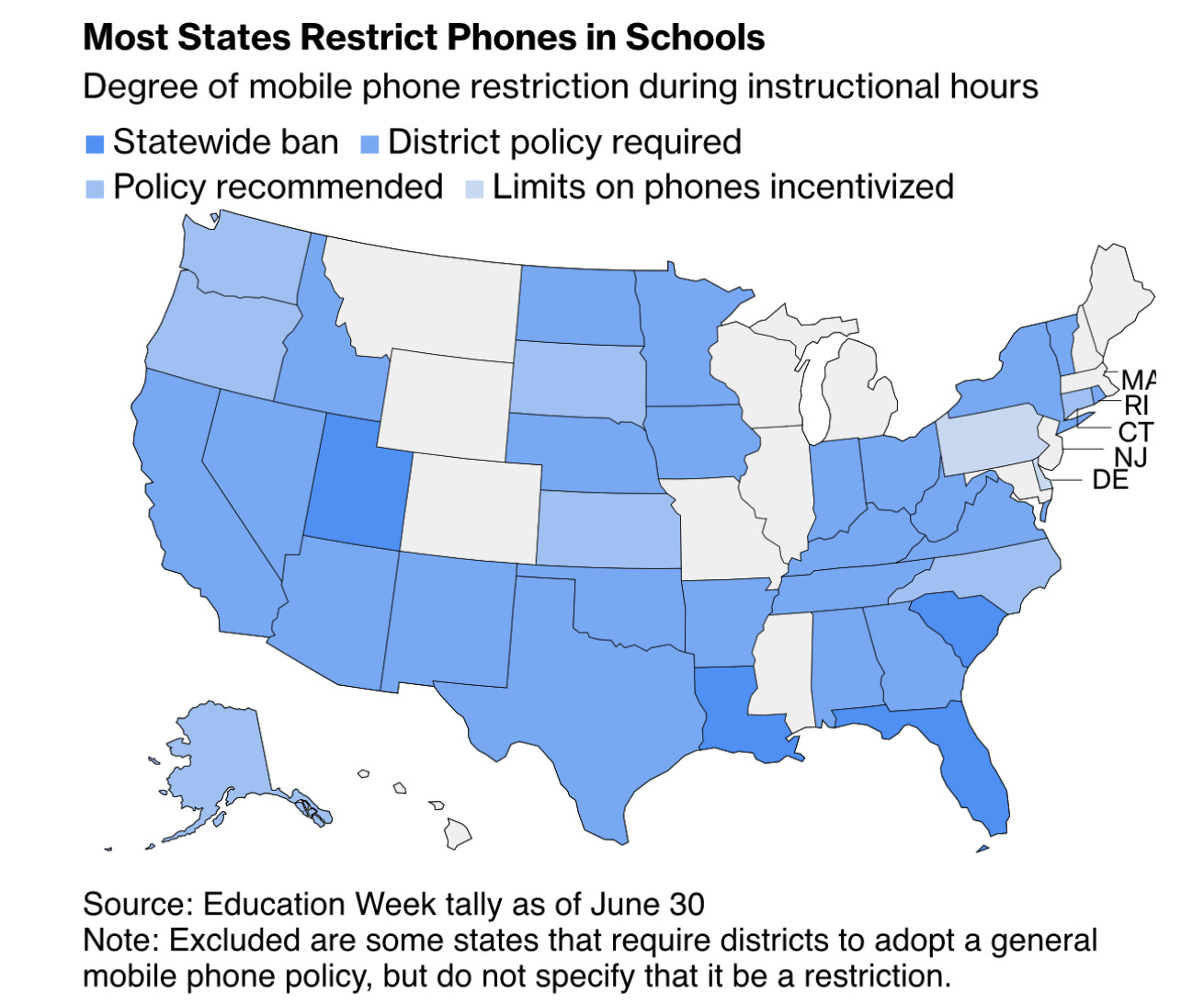

Republican and Democrat politicians don’t agree on much, but one of the things they do agree on is that kids shouldn’t have access to phones when they’re in school. Bloomberg has a story on this written by Mary Ellen Klas, although it’s behind a paywall. I’ll pull out some of the main points here. But first, here’s the map.

(Source: Education Week via Bloomberg)

Different States have different policies, obviously, but by the time that American schools head back after the summer,

students in most US states and DC will be required by law to turn over or turn off their smartphones during all or most of the school day, according to an Education Week tally.

The evidence also suggests that the schools that started doing this first have started to see improvements in educational performance and also an uptick in attendance levels.

Although the approach varies from state to state, the rationale is the same:

A growing body of research has found that the more time children and their developing brains spend on smartphones, the greater the risk of negative mental health outcomes — from depression, to cyberbullying, to an inability to focus and learn.

Some of this research was coralled by the American researcher Jonathan Haidt, in his book The Anxious Generation, which connected phone use by young people with “the explosive increase in rates of anxiety among young people.”

Kral quotes Carol Vidal, who works as a child and adolescent psychiatrist at John Hopkins:

Social media is intentionally designed “to expose users to an endless stream of content” which makes it addictive... That’s especially risky for children and teens, she said, “because their brains are still developing, and they have less control over their impulses.”

One of the front-runners in banning phones was a middle school in Kansas: it was an early decision by a new head, Inge Espjerg. She noticed a spike in online bullying at lunchtimes, and an increase in absences and suspensions, largely associated with bullying. As a result she and her staff decided to impose a rule at the start of the 22-23 that required students to turn off their phones at the start of the school day, and store them in their lockers.

The kids were OK with this, but the parents weren’t.

“I don’t think we really realized how much parents were reaching out to their students during the school day,” Esping recalled.

One thing they worried about, of course, was being able to contact their children in the event of a school shooting. The school went through an ambitious outreach programme to talk to parents, and also improved the school’s emergency alert system.

And the educational improvements were immediate:

In the first year, the school saw a 5% increase in their state assessment scores in both reading and math. School suspensions dropped 70% by Christmas and have remained at half the rate they were before the ban. And absenteeism went down from 39% to 11% — because taking phones away prevented many of the harmful social media comments that kept bullied kids from coming to school.

That’s just one school, of course—anecdata, as they say—but other schools report the same effects. In the year after Orange County in Florida introduced its phone ban,

fighting went down 31% and “serious misconduct” issues decreased by 21%.

A UNESCO report summarises some of the international evidence as to why phones harm learning:

One study which looked at pre-primary through to higher education in 14 countries found that it distracted students from learning. Even just having a mobile phone nearby with notifications coming through is enough to result in students losing their attention from the task at hand. Another study found that it can take students up to 20 minutes to refocus on what they were learning once distracted.

They also noted, based on research in Spain, Belgium and the UK, that the effects were worse for “students that were not performing as well as their peers.”

(Image via Rawpixel. Public domain.)

The American outcomes have been noticed in the Senate as well. Democrat Tim Kaine and Republican Tom Cotton have co-sponsored legislation to study the effects of mobile phone use in schools, and Democrat Elaine Slotkin has called for a ban on phones in every school classroom in America.

Inge Espjerg told Mary Ellen Klas that her school ban had another notable effect: the kids were just more engaged in what was going on around them:

[A]fter the ban, “kids were looking up and talking to one another,” especially in the lunchroom and as students transitioned between classes. “When you’d say, ‘good morning’ to them, they’d say ‘good morning’ back.”

From the perspective of social trends, this is moving very fast. It normally takes much longer for changes in policy like this to gain traction. And obviously the US is not the only country doing this.

A tiny bit of online research identifies that by the end of 2024 40% of countries worldwide—79–had banned phones in schools. This was up from 30%, or 60 countries, at the end of the previous year. And in addition, some of the earlier bans had become more stringent over the course of the year.

j2t#645

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Nicolas Colin's work is some of the best I've seen this year. Great summary.

And while I used to, I no longer can force myself to read through Azeem's regular hype firehose. Especially after he regularly regurgitated Ranga Dias's room-temperature superconducting fraud without even so much as pausing to ask a single skeptical question.