5 December 2022. Migration | Roads part 2

Bringing climate migration to life. // How Britain fell out of love with roads.

I try to publish Just Two Things three days a week, but there are sometimes updates to recent pieces and corrections to fit in. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

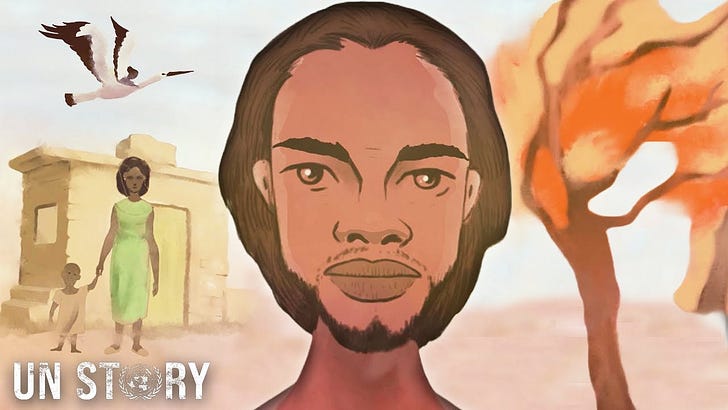

1: Bringing climate migration to life

South Africa’s Daily Maverick has a story about an animated video (4’40”) about climate migration by the Iranian illustrator Majid Adin, who is now based in Britain after claiming asylum here. The video was commissioned by UN Video for COP27:

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), more than 20 million people every year are being forced to leave their homes because of extreme weather events due to the climate crisis, including abnormally heavy rainfall, prolonged droughts, desertification, environmental degradation, sea-level rise and cyclones

Iran, says Adin, is already suffering from water scarcity—which is the ‘canary in the coalmine’ for climate challenges:

He describes his home (Mashhad, in northern Iran) as “completely dried up, where people are fighting for their water”. Iran’s cheap oil has “sucked away” much of the land’s water... Iranians protest about the country’s dwindling resources, about the regime, about rigged elections and about the lack of human rights.

Adin was arrested in Iran in 2010 after starting a blog that showcased his political cartoons (he describes the cartoons as “innocent”). The cartoons “offended the religious authorities,” and he spent five months in jail.

The Daily Maverick story is unclear on the detail of some of this, but after release he still faced trial and his passport was confiscated. He fled the country, but his route to the UK was as grim as for any migrant. From Turkey,

he took a makeshift boat across the Mediterranean Sea to Greece — the boat collapsed and he almost drowned. A Greek man saved his life and he eventually arrived at the Calais Jungle (Camp de la Lande) refugee encampment in France. He was trapped at the French encampment for six months before he managed to successfully flee to the UK.

He made more than 20 attempts to get to the UK from there, eventually crossing the channel successfully in a refrigerated vehicle:

“The suffering… there is nothing like it,” Adin says. “Being forced to leave my homeland and the difficulties I faced … my heart still hurts.”

Adin’s big break was winning a competition to make a video for Elton John’s song ‘Rocket Man’. His entry for the competition drew on his experience of being a refugee—which can be seen in the music video. Given the lyrics, it’s an interpretation that works:

There’s a couple of tediously obvious points to labour here, for those who get obsessed by people seeking asylum in the UK, or anywhere else, for that matter. (As well as the sadly necessary reminder to Britain’s Conservative MPs that seeking asylum in not illegal).

The first is that it’s always a desperate decision when you have to leave, especially knowing the risks and hardships ahead. The second is that focussing on the boats or trucks overlooks what asylum seekers contribute when they get here. But it’s always easier to de-humanise people than to help to restore their humanity.

2: How Britain fell out of love with roads

The first part of this post, on Saturday, traced the rise of the motorway, from the mid-50s to the early 1970s. It’s an extended review of Joe Moran’s 2010 book On Roads. This takes the story through to the 2010s.

In 1972, Britain’s motorway system reached a thousand miles in length. One of the last significant motorway sections, a Midlands extension, meant that from the so called Midlands ‘golden triangle’ you could reach 92% of the U.K.’s population and return in a single working day.

(‘Imagine You Are Driving’, 1998-99. Julian Opie, The Tate Gallery. © Julian Opie. Photo: Tate.)

But even as the motorways passed the 1,000 mile mark, the public mood and the political mood was starting to shift. Protests against London’s Westway in the ‘60s and ‘70s – one part of a long planned "motorway box" around the centre of London — drew on 1960s counterculture. In 1970 the London pressure group Homes Before Roads contested the Greater London council elections, and gained 100,000 votes, if no seats. By 1972, the Department of the Environment said "the day of the supremacy of the motorcar and the road builder has come to an end."

It is another sign, perhaps, that 1972 does indeed represent “the high water mark of modernity”, which I wrote about here a couple of weeks ago.

Although this was the end of the idea of the big urban motorway, the roadbuilders did keep going. The Labour government that came to power in the 1970s hadn’t got the memo. The Environment Minister Anthony Crosland, now in charge of transport, believed that the car was a force for social mobility, and approved the building of the M25. London’s orbital motorway was opened enthusiastically by Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1986.

The end of the motorway age was marked by increasingly complex and bitter protests at Twyford Down on the M3, at the Newbury bypass in Berkshire, and in East London, where the M11 Link Road was being built. Tactics became increasingly sophisticated: lock-ons, tunnels, and treehouses all evolved during this time. As Moran observes, it was astounding that no one died.

There was also some wit: East London declared the independence of ‘Wanstonia’ and applied to join the United Nations, as anti-Westway protesters had done 15 years before with ‘Frestonia’ in Notting Hill.

(Campaign posters from the campaign against the M11 Link road. Source: Urban75.org)

In East London as houses were cleared to build the link road they would be squatted by protesters, and the police response became increasingly aggressive. The protests did not prevent any of the roads from being built, but they changed the way that road building was perceived. When the Conservative government was looking for budget cuts, the capital spending on the roads program was an easy target.

I don’t think it’s coincidence that images of roads appeared in the British art of the 1990s. Jonathan Parson’s ‘Carcass’—part of the Young British Artists ‘Sensation’ exhibition’—severed the roads from the map, and a hung them up. Julian Opie’s sequence ‘Imagine You Are Driving’, seen above, harks back to the early excitement of driving on almost empty roads. Graeme Miller’s ‘Linked’, which I’ll come back to, is the direct result of his being swept up, wrongly, in the East London roads protests.

When the new Labour government came to power at the end of the 1990s, the political noise was all about improving and increasing the use of public transport. In 1998 a government White Paper, "A New Deal for Transport", cancelled many road schemes. Roads would, it said, be built only as a last resort. 2000 was the first year since the 1960s when there was no motorway building of any kind in Britain.

But even so, road building schemes and road "upgrading" schemes continued, hidden behind the apparently neutral, and apparently technical, language of the new Labour "New Approach to Appraisal" (NATA), underpinned by some conveniently calculated cost-benefit numbers:

Every minute a new road saved a driver was worth 44p – and all of those 44ps added together over the road is projected 60-year lifespan could be offset against the cost of building it. But a minute saved for a bus user was only were 33p, and for a cyclist 28p. (243)

Moran draws on Alan Weisman’s book The World Without Us to describe what happens when you stop using roads. They disappear surprisingly quickly. Freezing and thawing breaks up the asphalt, and the water runs through the cracks.

After a decade, the road would be overgrown with vegetation; a decade later it would be impassible except in the sturdiest off-roader. (250)

There are ghosts in the roads that have been built as well. Graeme Miller, whose house was ransacked by police during the M11 protests, got his revenge by creating an audio work, ‘Linked’, built around the voices of those who had been displaced by it.

The work is embedded in the landscape around 3 miles of the motorway, with recordings played by transmitters and lampposts on the nearby roads. The transmitters are under guarantee for 100 years. The stories about the M11, and the people that it displaced, might outlive the road that uprooted them.

j2t#403

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.