03 December 2022. Roads | 2022

How Britain fell in love with roads. // Tom Whitwell’s 2022 ‘52 Things’ list

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: How Britain fell in love with roads

This is the first part of an extended two-part piece about Joe Moran’s book On Roads. Part 2 on Monday, on how Britain fell out of love with roads again.

I noticed Joe Moran’s 2010 book On Roads in the local library, and I’m interested in roads and like Moran’s work. (I’ve also read his books on failure and on writing.) He doesn’t mean roads in general. This is a cultural history of British roads in the sixty years between the heady excitement of the first motorway openings to the road protests of the 1990s and 2000s, even if tracing that story has deep roots.

Moran describes the book, published in 2009, as “a study in the living memory of roads”. It goes back three generations, to the moment in the 1950s when first the Preston bypass—the first instalment of the M6–and then the first section of the M1 were opened, to quite a lot of collective excitement.

This also means that it is

“a study of how our thoughts and feelings change imperceptibly over time while seeming as natural and inevitable to us as breathing.”

It is, therefore, also a study in how values change.

This explains how the geographer Peter Hall can write an excitable book in 1963 imagining the year 2000—there was a lot of this kind of thing around back then—-in which huge elevated expressways stretched from the centre of London outwards through the suburbs. And, 40 years on, he can say that the way in which Britain fell out of love with the roads is "one of the biggest and most sudden psychological changes of the 20th century ".

Moran’s account is thematic rather than chronological. It ranges across road design, numbering schemes. motorway catering, road rage, speed limits, tarmac, and the politics and protests that marked the end of high-profile road building programmes in the 1990s and 2000s.

I am focussing here on the signs that tell the story of Peter Hall’s “sudden psychological change”, but there is much more here: J.G. Ballard, G.K. Chesterton, The Smiths, Marc Auge’s ‘no-places’, the progressive band Hatfield and the North, the architect Will Alsop, Heathcote Williams, George Orwell, John Betjeman, Stonehenge, and, of course, the Roman road-builders all pop up, among a far larger cast list.

Moran captures well the excitement of the opening of the first part of the M1. It had four different press openings, all of which generated gushing headlines. When motorists got onto it they drove their cars beyond their capabilities: tyres blew out, big ends were wrecked. The AA was called out every six minutes.

As the French theorist Paul Virilio said, the invention of the car also means the invention of the car crash. Wolfgang Sachs has noted that the car arrived, culturally, at the same time as the celebration of measured speed—with the invention of the modern Olympics and the cycling time trial.

It took a decade before Barbara Castle, as Transport Minister, imposed speed limits on motorways, along with a slew of other traffic laws, and she was met with a fair amount of hostility. But it seems that imposing limits increased the average driving speed; before the 70 mph (110 kph), drivers tended to drive in the 50s (80s kph).

From a futures perspective, it’s worth noting the aspirations of roads advocates in the 1950s and 1960s, even their utopianism. The shadow of Le Corbusier strides across them.

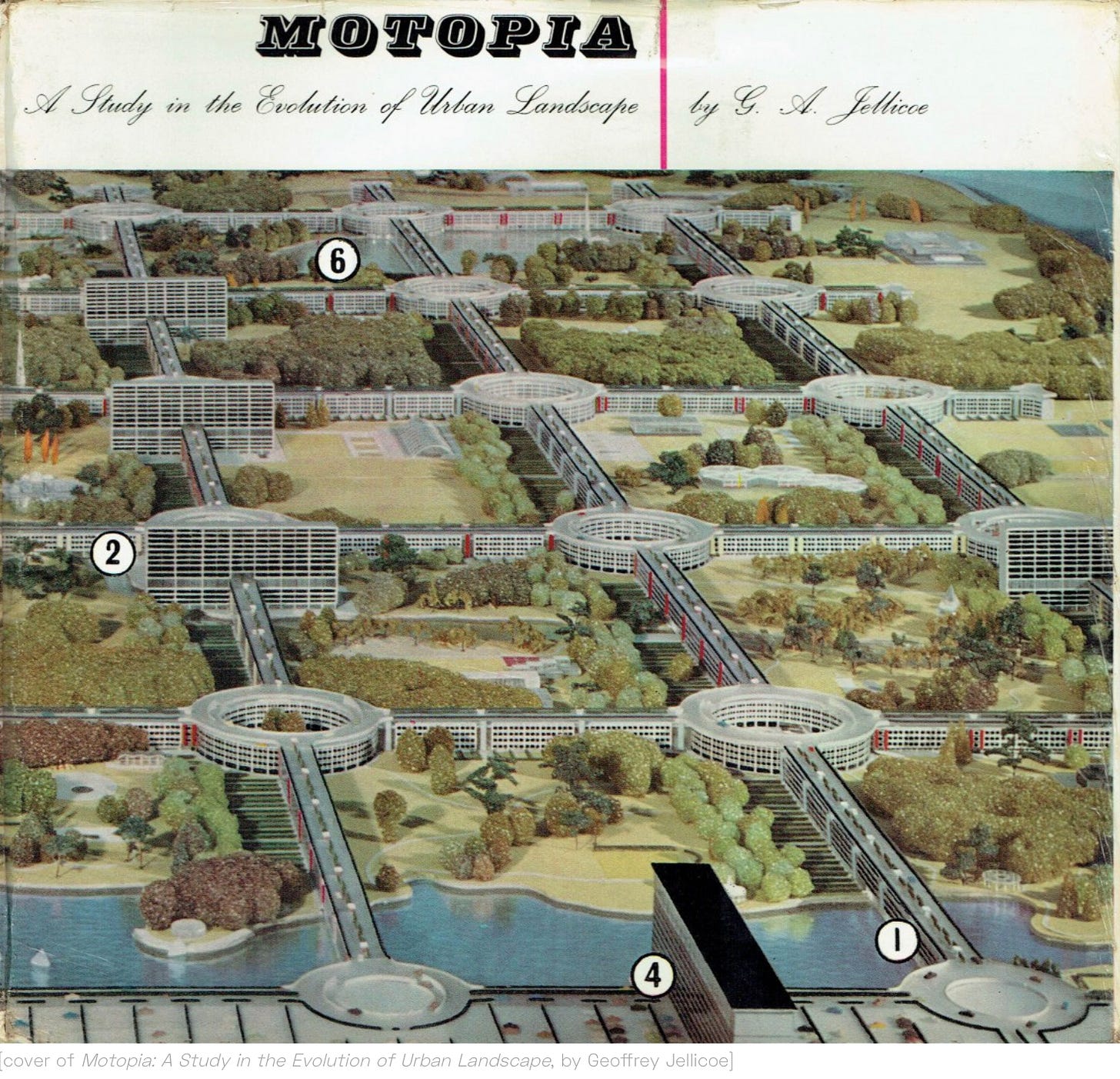

Gordon Jellicoe published plans for "Motopia", sponsored by the Pilkington Glass Company, in 1959, in which a town of 30,000 inhabitants would be built around an elevated grid of roads raised 50 feet (15m) into the air. The ground would be reserved for public parks and canals. Jellicoe claimed that the sound and smell of the cars would disappear upwards.

Jellicoe did have an actual town in mind for this project – Staines, in the shadow of Heathrow, which is best described as "nondescript". Moran notes that Jellicoe’s account of separating the people from the cars is close to the way in which the new town in Milton Keynes was designed, more or less at the same time.

The normalisation of roads also happened in other ways. The nature writer Robert McFarlane has observed that the road atlas makes it appear that Britain has become nothing but roads. This makes it easier to read, of course. But if the roads as they appear in the atlas were built a scale, they would be hundreds of metres wide. The railways, meanwhile, are thin wisps.

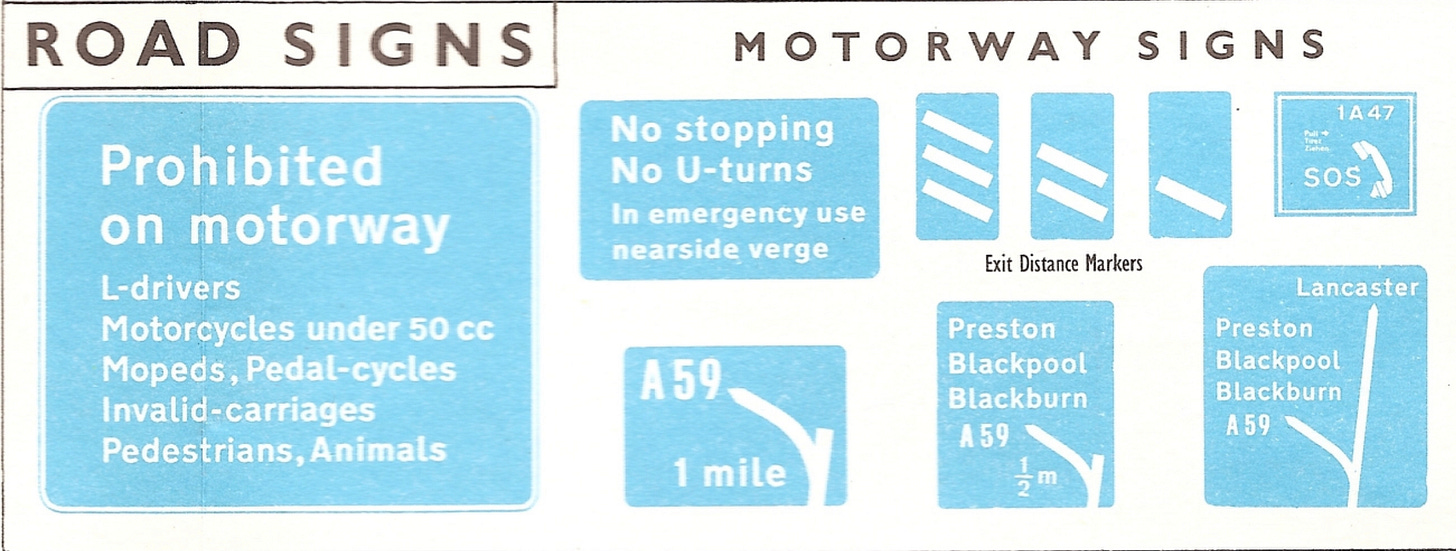

There was a complex cultural battle over motorway signage: the lead designer, Richard Kinnear, had already cut his teeth on the signage for the new Gatwick airport. His designs, with sans serif typeface, using both upper and lowercase fonts, were controversial. A counter-movement proposed a serif alternative.

(Image: Mikey Ashworth/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

Moran suggests that there was a class element to this opposition. Sans serif had "plebeian" connotations. Oxfordshire’s county surveyor had tried out something similar in the 1950s, and was instructed by the DFT to remove the signs.

Kinnear and his colleague Margaret Calvert went on to redesign non-motorway signage as well—and pioneered a huge shift to lowercase lettering in British public life and indeed, the ascendancy of sans serif typefaces.

Moran argues that these roadsigns belong to "hopeful era of postwar reconstruction". The art historian Joe Kerr called them "the corporate identity of the welfare state". In theory they were universal signs that were intended to give quotes clear and legible directions to everyone." Or, at least, to everyone who drove. In his book The Psychology of Everyday Things (although Moran doesn’t pick this up), the designer Donald Norman celebrates the British motorway sign, and its conventions, as a model of visual and conceptual clarity.

The signs were contested in other ways. The Welsh campaign for dual language signs was—eventually—successful, and it was followed by a similar campaign by Gaelic speakers. The first Gaelic signs, on Skye, were a condition imposed by the Edinburgh merchant banker Ian Noble on a sale of land for a new road.

The development of the motorway network was surprisingly rapid. In 1962, the Transport Minister Ernest Marples announced plans to build 1000 miles of motorway in a decade at a rate of more than a mile a week. Surprisingly this was achieved—perhaps a marker of what states can do when they have capacity—when the "Midlands link" of the M6 opened in 1972. This was transformational. It opened up the new age of just-in-time deliveries and “the big shed":

by centralising the warehouse’s stock and keeping goods moving, firms could release cash flow, perhaps even sell things before they had to pay for them.… "Logistics" was this new art of moving stuff around, and the system’s beating heart was the big shed. (149)

Or, as the architectural critic Martin Pawley wrote:

Like strips of shredded truck tyre, you can find Shedland anywhere there is a motorway.

Welcome to the modern world. Just at the point in history when we needed to manage our consumption, we had installed all the conditions for a fossil-fuel driven boom in consumerism.

Part Two on Monday.

2: Tom Whitwell’s 2022 ‘52 Things’ list

(Photo: Leo Reynolds/flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Tom Whitwell has just published his entertaining annual post on ‘52 Things I Learned in (insert year here)’ and it doesn’t disappoint. Here’s a small selection of the Things.

Heavenbanning is a hypothetical way to moderate social networks. Instead of being thrown off the platform, bad actors have all their followers replaced with sycophantic AI models that constantly agree and praise them. Real humans never interact with them. [Asara Near]

37 per cent of the world’s population, 2.9 billion people, have never used the Internet. [International Telecommunication Union

40% of global shipping involves moving fossil and other fuels (oil, gas, wood pellets) around. More renewables (solar, wind, nuclear, geo), means fewer ships. [Bill McKibben]

Consumer goods branding existed in the ancient city of Uruk, Mesopotamia over 5,000 years ago. ‘Temple-factories’ mass-produced, packaged and labelled goods like bread, beer, wine and woollen clothes. [David Wengrow]

Researchers asked 100 people whether a reasonable person would unlock their phone and give it to an experimenter to search through. Most said no. Then the researchers asked 103 other people to unlock their phone and give it to them. 100 of them complied. [Rob Henderson]

The push button was a controversial new interface when it became popular in the 1880s. [Rachel Plotnick via Matthew Wills]

Read the whole thing. Of course.

j2t#402

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.