9 July 2024. Politics | Freezing

3 or 4 things I noticed about the UK’s general election // Reducing emissions by making freezers a bit warmer. [#586]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

With apologies to readers who are less interested in British politics. Normal service will resume later this week.

1: 3 or 4 things I noticed about the UK’s general election

It takes time to think through what happens in any election, and in some cases you need to wait for people to dive into the data. But I think there are a few things we can say already with some confidence.

1. British elections are about winning seats

There’s been a lot of discussion about how Labour managed to achieve a landslide in terms of seats on 33.9% of the popular vote. And the answer is that they were brutally efficient in focussing on seats they thought they could win—sometimes even sending candidates away from seats they were going to lose to campaign elsewhere.

But the British election system—which is undoubtedly problematic and desperately needs to become more proportional—doesn’t reward parties for winning vote share. The other problem is that under the First Past The Post, we don’t actually know who many people’s first preferences are. If someone votes for a party in their constituency that is sure to lose, we can be pretty sure that they support those parties. For the rest, we’re making estimates of tactical voting.

The efficiency of the vote is seen in the compression of majorities—which shows a distinctively different shape from previous elections.

(Tom Calver, Twitter/X, via Political Betting).

If the Conservatives had been this efficient, the commentary would be full of people saying that they were historically the most ruthless election-winning machine in Europe.

A note here on turnout, which was down around seven percentage points. But during the election night coverage, I didn’t hear anyone ask how much this might have been to do with the voter ID laws. These applied to a General Election in the UK for the first time, and they were fairly evidently introduced by the Conservatives to suppress the votes of likely non-Conservative voters.1

The Electoral Commission, which produces a statutory report on each election, found after the May 2023 council elections (where fewer people voted), that

around 4% of all people who said they did not vote at the elections on 4 May listed the ID requirement as the reason – 3% said they did not have the necessary ID, and 1% said they disagreed with the new requirement.

In the House of Commons Library summary, they noted that:

some people found it harder than others to show accepted voter ID, including disabled people, younger voters, people from ethnic minority communities, and the unemployed.

Polling this week by More in Common found that 3.2% of people said they were turned away from a polling station2—including a disproportionately high number of ethnic minority voters. They also found that

6% of people said the ID requirements had affected their decision on whether or not to vote and that they then did not vote.

So it’s possible that the story about low turnout that has dominated some of the coverage may have a simpler explanation than people not caring about voting. Voter suppression isn’t just about party advantage.3 It’s also a way to de-legitimate democracy.

2. The discourse about ‘all politicians are the same’ is a deliberate right-wing political strategy

There’s a story by Salman Rushdie called Haroun and the Sea of Stories, written when he was under a fatwa and couldn’t get out much, in which Haroun and his father journey to the source of the sea of stories to try to work out why it is polluted.

For some reason this came to mind when I was looking at some of the election coverage. The reason I say that this is a deliberate right-wing strategy, is because corruption and elite indifference infects impressions of the whole political class—even those who are not corrupt and are not indifferent.

Here’s a chart on that from the Financial Times.

(Source: NatCen via Financial Times).

The one at the bottom should be reversed for consistency (or NatCen should ask this question differently), since the Agree/Disagree statement here are the other way around from the other four questions.

I was also struck by a qualitative version of this, in which—just before the election—a politically interested nearly 30-something said that she was having problems deciding who to vote for, for the same reasons.

Reading the party manifestos, watching the television debates and attempting to decipher which party best represents my beliefs and values has been harder than ever... “It feels like the two main parties are just the same,” one friend told me in the pub last week. “I don’t know who stands for what or who to even trust anymore,”, another friend said on the phone last night.

She’s a Muslim woman—one of the many alienated by lack of support from the Labour Party for women MPs of colour who have faced terrible online abuse.

But there’s an underlying point here: finding ways to rebuild trust in what politics is for, and what political parties can do if they are more than vehicles for the rich, is going to be a critical first step for the Labour government. Hence Starmer’s early comments over the weekend that “politics can be a force for good.”

3. Reform is the last bastion of Brexit

A striking chart shows the correlation between Reform votes and Brexit votes—in a way that is no longer true for Conservative voters.4 The dots here are constituencies: 2024 vote share in on the vertical axis; 2016 Brexit vote share (which will have been adjusted because of the new boundaries) is on the horizontal axis.

(Source: Press Association/ ONS, data design by Guardian)

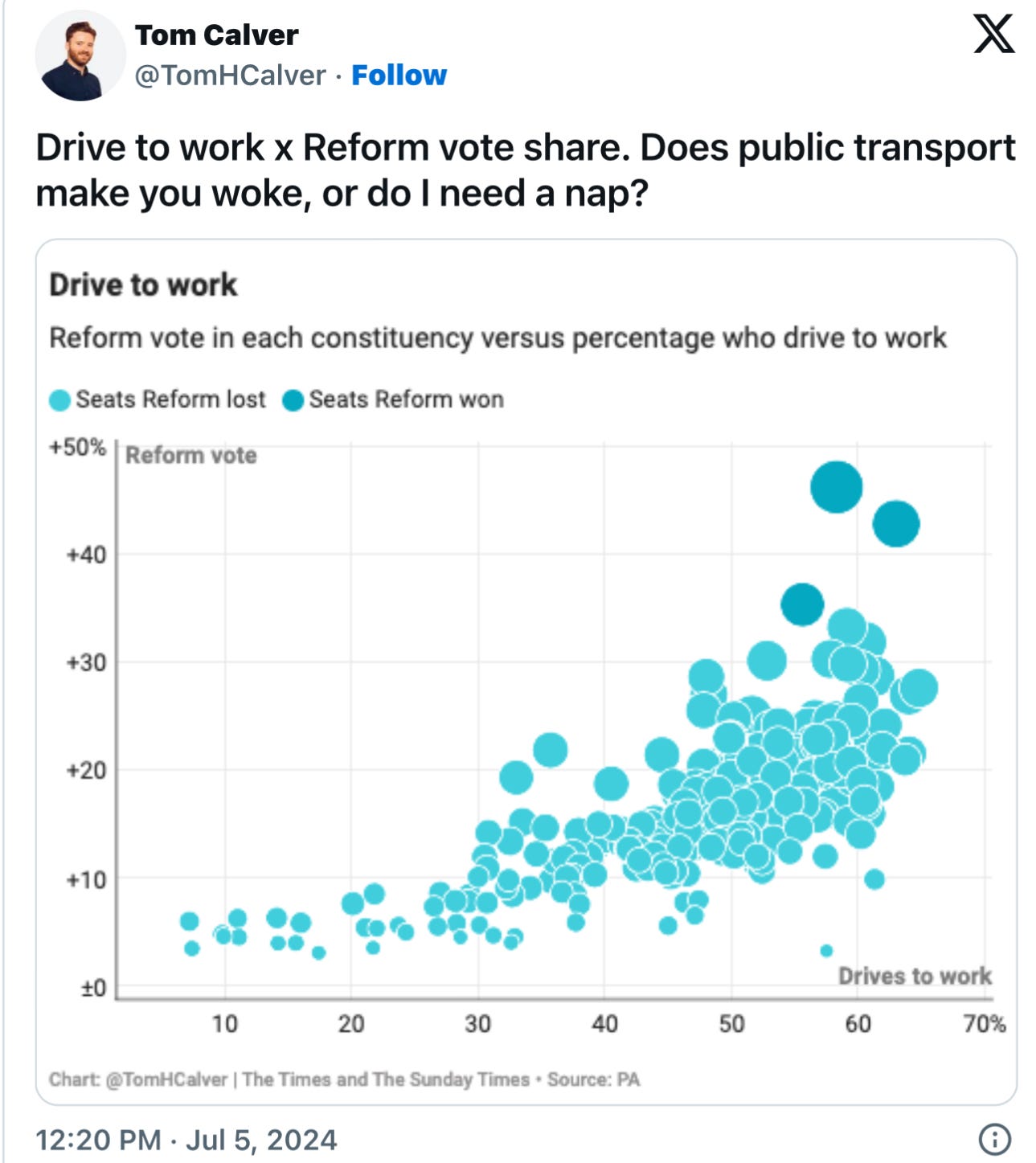

But there’s also a wider point here—that it’s also a home to people who feel left behind. (I wrote here recently about the connection between far right and hard right populist parties and internal emigration and local decline.) And this is also true of Reform. Tom Calver had a chart on this too, but made a joke about it.

(Source: Tom Calver, Times and Sunday Times)

It is at least as likely that Reform voters live in places where the bus services simply don’t work well enough any more. Or at all. Al Jazeera noted the decline in a visit to Clacton, the run-down coastal town that is now represented by Reform’s leader, Nigel Farage.

There are hardly any customers at seaside cafes, several shops have been shuttered, and young homeless people aimlessly mill around a central square...“Clacton is a seaside town that’s falling apart,” says Alexander Armitt, a 62-year-old who is medically retired, having worked in printing. Farage tempted him away from his “lifetime Labour supporter” status, he says.

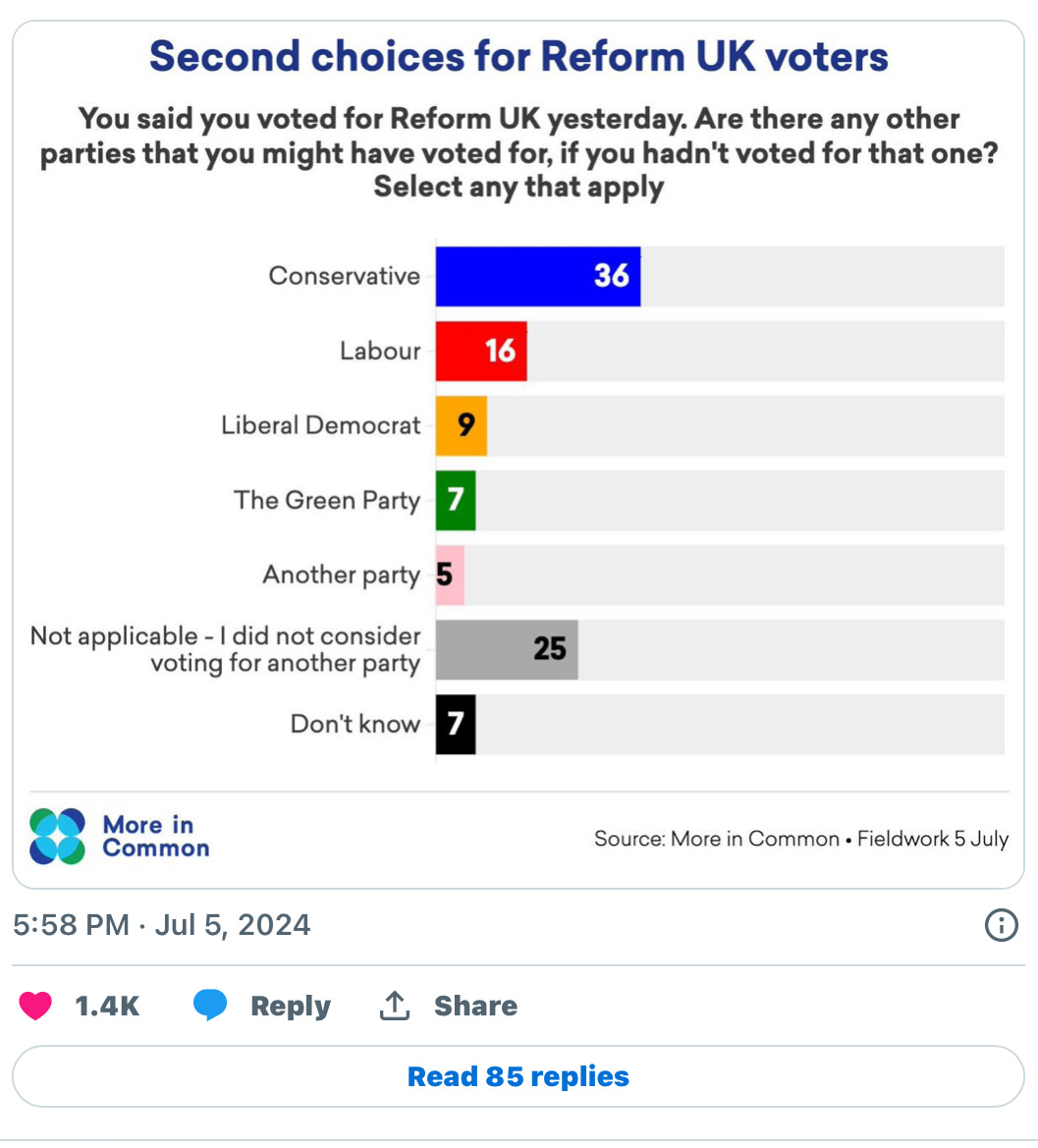

That’s the other significant thing about Reform voters. They are, emphatically, mostly not Conservative voters in disguise. The people ‘hypothetically’ recalculating the election result by combining Conservative and Reform voes are wasting their time. A quarter of them would not have voted for anyone else, had Reform not been standing, just over a third would have voted Conservative, and around one in six would have voted Labour.

(Source: More in Common, via Jo Michell on Twitter/X)

4. The political divide in Britain is between people of working age and people who are retired

This was fairly true at the last election, but it is emphatically true now. The age at which more people voted for the Conservatives than the Labour party is now 64–this has increased by almost 20 years since the last election.

(Source: FocalData)

This does open up some lines of policy that might have a real impact on people, despite Britain’s tight economic position. Because we have had a government for the past 14 years that pandered, endlessly, to the concerns of the retired, both directly and indirectly.

This means that there is scope to speak to those working age voters with policies that might increase their security without costing a fortune—whether that is increasing levels of protection in the workplace, or reintroducing (and improving) the Renters (Reform) Bill, which fell when the election was called, or redesigning the energy pricing system so it benefits the energy companies less and energy customers more.

Because the last thing to say about our new government is that it is much more like the population as a whole, in terms of its education, than the last one, and also has a broader range of experience before coming in to politics. In other words, it’s more diverse, in multiple ways. Which may, who knows, improve the quality of its decision-making.

2: Reducing emissions by making freezers a bit warmer

Jeremy Williams’ excellent blog Earthbound has an intriguing piece about a business-to-business campaign to cut emissions by reducing the recommended temperatures in the cold chain—the supply chain system that brings frozen foods from the factory via specialist trucks to the supermarket.

(‘Refrigerated (reefer containers. Photo: JAXPORT/flickr CC BY 2.0)

The campaign, called Move to -15, is trying to shift the temperature at which cold chain goods are shipped to -15 degrees from -18 to -23. If this seems technical, the effects of success would be significant. As Williams notes:

Moving to -15 would save 5-7% of the energy use in the supply chain on average, 10-12% in some contexts. If that doesn’t sound like a huge amount, it’s worth remembering just how big the cold chain is across the globe. The global energy saving at -15 would be equivalent to twice the annual energy consumption of Kenya.

The story of the campaign is an interesting example of the challenges involved in reducing emissions more generally. It’s not a lock-in problem—you don’t have to change the equipment—but is an alignment problem, because lots of different stakeholders need to agree the move.

Of course, the first question is: would it be safe? Food consumers (and health regulators) aren’t fond of food poisoning, and food companies therefore try not to do this.

The answer to this question is yes. The -18 to -23 degree range was developed in the early days of freezer technology, close to a century ago. But although both logistics and freezer technology have come on a long way since then, the cold chain still operates at those temperatures:

The freezing process begins at 0, and food remains stable and entirely safe at warmer temperatures. What matters more is the speed and efficiency of the moving and handling along the way. Inefficient logistics won’t deliver a stable product even at -18, whereas a well functioning system would be perfectly fine at -15.

Nomad Foods, Europe’s biggest frozen food company, has been a leader in this campaign, and it has commissioned research on safety. Their brands include Birds Eye, Findus, and Iglo, as well as Goodfellas Pizza:

They studied a variety of foods at four different temperatures, from -9 to -18, and assessed any change in quality over time. None of the foods showed any deterioration at -15.

As a result they have now put their weight behind Move to -15. As Williams says, this coud be the difference that makes a difference:

They have the most to lose if the industry were wrong, and so their support could well nudge anyone who was on the fence.

In fact, it seems that, generally, -12 is safe for frozen foods—so -15 degrees has three degrees of safety. -18 degrees is over-freezing.

With one significant and important category exception: ice cream.

While almost every food is fine at -15, ice cream is an exception and can crystalise in unpleasant fashion if it gets much warmer. There are a couple of ways around this. One is to keep ice cream freezers at a colder temperature, since they’re often in their own freezer anyway.

But it turns out that this isn’t the only approach. Unilever got its food scientists to develop an ice cream that is stable at -12 degrees, and has given away the IP involved in its research so anyone can use it, to remove this important obstacle.

The Move to Minus 15 Coalition is doing the things you’d expect an effective industry campaign to do. It has got support from much of the global shipping sector, and is building support in other parts of the logistics sector. It has appointed a chair with a significant reputation in the sector. Coalition members are using industry events—in this case the S&P Global Premier Shipping and Supply Chain Conference—to convene in-person meetings and agree how to build it further.

All of this is more or less invisible to consumers. Change is likely to be slow, although like other campaigns to reduce emissions it could reduce supply chain costs by between 5% and 7%, which would be an incentive even to the sceptical.

Williams’ article did make me realise that my own freezer might be set too cold, since most domestic freezers are set in the -18 degrees range, or a bit more. I may go and nudge it towards -15.

j2t#586

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The ‘presenting problem’, of in-person voter personation has run to small single figures in previous years and the scheme cost £180 million. A sledgehammer to crush a microbe.

On the face of it this figure seems high; the 6% figure below seems more in line with research from the impact of voter ID on local elections.

The same legislation changed England’s Mayoral elections from a Transferable Vote system, designed to make sure that Mayors had the support of a majority of those voting in their areas, to First Past The Post, to increase the chances of Conservatives winning.

Although the Conservatives don’t seem to have won seats in strong Remain-voting constituencies.