5 October 2024. Modernity | Simulation

Facing up to the limits of modernity—or trying to bust them // ‘Gaming’ an attack on the Capitol in 2025 [#606]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Facing up to the limits of modernity—or trying to bust them

Adam Kirsch’s The Revolt Against Humanity is really too short to be a book, coming in at less than 90 pages, if we don’t count the two pages of ‘further reading’. So it’s more monograph length, and seems to be one of a number of essays published by Columbia Global Reports that take a left-field view of topical subjects. It was published last year. I thought it was worth looking at how they described themselves: “Our books are short—novella-length, and readable in a few hours—but ambitious. They offer new ways of looking at and understanding the major issues of our time.”1 It was pubished in 2023. I picked it up on impulse at my local library.

“Humanity” is the key word here, and the book could easily be called Beyond Humanity without doing any harm to his argument. Kirsch is a literary critic whose day job is at the Wall Street Journal’s weekend Review section. His argument in this book connects those writers and activists who are relaxed about the end of the human species—he characterises them as “antihumanists”—and those philosophers and technologists who see humanity transcending itself through technology (“transhumanists”). On the one hand, for example, the Dark Mountain Project gets a certain amount of airplay; on the other, Nick Bostrom pops up from time to time.

There’s a kicker to this argument, and it’s clever but I’m not sure it works. The kicker is that although the two groups seem to be separated by a gulf in thinking, in practice their willingness to see humanity vanish, albeit in different ways, means that they are closer to each others’ perspectives than either group would acknowledge. And both combine in opposition to humanist perspectives of our species.

Because Kirsch is a literary critic, the range of voices here is beyond the usual suspects, and includes critics and writers as well as philosophers. There are engaging historical references. The tone is set from the very beginning, which also gives a flavour of both the style and the argument:

"Man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end." With this declaration in The Order of Things (1966), French philosopher Michel Foucault heralded a new way of thinking that would transform the humanities and social sciences. Foucault's central idea was that the ways we understand ourselves as human beings aren't timeless or natural, no matter how much we take them for granted. (p.9)

Foucault’s argument has, I think, become commonplace in the intervening 60 years: that the notion of ‘man’ was a product of the Enlightenment, which is an indication of both how radical it was at the time, and how influential Foucault has been. There are, though, different ways to imagine the “end” of “man”:

From Silicon Valley boardrooms to rural communes to academic philosophy departments, a seemingly inconceivable idea is being seriously discussed: that the end of humanity's reign on Earth is imminent, and that we should welcome it. The revolt against humanity is still new enough to appear outlandish, but it has already spread beyond the fringes of the intellectual world. (p.10)

That’s all from the first couple of pages, so it gives a sense of the argument he makes. If the book is short, it also covers a lot of ground, and I’m not going to be able to do more here than give a flavour, looking briefly at a couple of passages in each half of his argument.

Michael Boulter, for example, argues that humanity’s destruction goes back thousands of years, to the Stone Age and even earlier. For example, before humans arrived in Scotland, there was a stable, balanced, ecosystem:

Humans didn't need bulldozers to destroy this demi-Paradise; the technologies of 2100 BC, such as fire and herding, were enough to shatter it beyond repair... Paleontology suggests that humans hunted many large mammals to extinction in Europe—including the mammoth, woolly rhino, elk, hyena, lion, bear, and tiger. (p.33))

Bringing that into the present, the cultural theorist Claire Colebrook describes our era as one of “species guilt and preliminary mourning”.

There’s a discussion of the development of “object-oriented ontology” as a philosophical approach that seeks to remove the centrality of the human. Richard Powers’ attempts this fictionally in The Overstory,

whose theme is that trees are superior to humans.

The transhumanist views of the world are better rehearsed in the mainstream. Silicon Valley is always good at getting attention. Inevitably, Ray Kurzweil appears: the singularity is still near, apparently.

But a couple of passages can stand for this argument. The first is from the Transhumanist Declaration of 1998:

the declaration calls for using technology to broaden "human potential by overcoming aging, cognitive shortcomings, involuntary suffering, and our confinement to planet Earth." (p.55)

Kirsch summarises the transhumanists like this:

The only thing that makes humanity unique, transhumanists believe, is our ability to compensate for our biological weaknesses with the power of technology... It's not recent technologies like pacemakers that make us cyborg-like; we have always been cyborgs, because technology has always been a fundamental part of being human. (p.64)

As I read the essay, I found myself getting uncomfortable with the underlying argument, but without being able to quite put my finger on why.

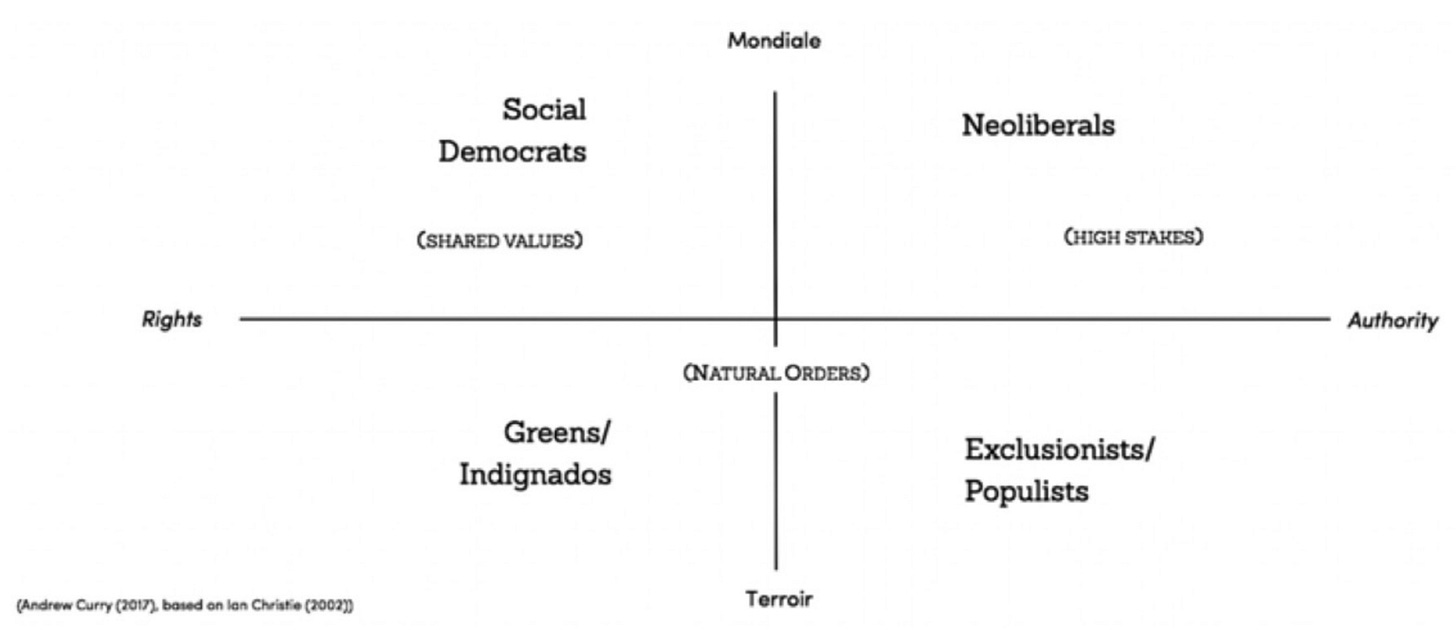

Eventually, I remembered a schematic of political views that was initially developed by Ian Christie in the early 2000s and which I adapted for an article about populist politics in 2017.

(Source: Ian Christie, Open Democracy (2002), adapted by Andrew Curry (2017)).

Christie’s original article had three groups, in my summary:

a squeezed “shared values” world of social democracy; a “high stakes” neoliberal world which produced losers as well as winners; and the emergence, or perhaps re-emergence, of parties based on what he called “natural orders.”

“Natural Orders” had both left and right orientations:

it contains protests by local and national interests against the homogenising, top-down capitalist forces that are shaping the values, tempo, environments and organisation of modern societies.

My adaptation was to split these two different orientations out from each other.

And when I’m looking at these two groups that Kirsch argues are converging on each other, they are in different corners of this schematic. The “end of humankind” thinkers are at the bottom left, about ‘terroir’, or place, and about rights—but rights for non-human species.

The “techno-humans”, on the other hand, are versions of the neoliberals in the top right. They’re global, unconcerned with place, and they are, at heart, authoritarians.

The dividing lines between these two groups are, on the one hand, a widely drawn view of rights, and, on the other, a celebration of modernity. These both emerged in the 18th century, but one is, essentially a political and legal—and inclusive—view of the human and of other species, and the other is essentially an economic and individualist view. They have fundamentally different views of power.

In short, the ‘antihumanists’ think that our species need to come to terms with the end of the long 400-year project of modernity, and the ‘transhumanists’ think that it’s possible for at least some members of the species to transform themselves to continue the modernity project.

Although I disagree with his conclusions, The Revolt Against Humanity was a good read, if only for the range of thinkers and writers that he covers, some of the historical and cultural references, and the elegant summaries he constructs of the lineaments of their thinking. I thought I knew this literature quite well, but I was discovering new people all the way through.

Read more:

Reckoning with life in the ruins of modernity, February 2023.

The end of modernity and the crisis of meaning, November 2022.

2: ‘Gaming’ an attack on the Capitol

Storyville: War Game was shown last week in the UK on the BBC, and is a documentary film about gaming the future. Gaming a very specific future, in fact: after the violent attack on Capitol Hill in 2021, it games the 2024 American Presidential election in the event that the election result is disputed. It was directed by Jesse Moss and Tony Gerber, and is on BBC iPlayer, for readers who have access.

The trailer is here:

A onscreen caption early on explains the set-up:

On January 6, 2023, a group of former military personnel and current and former government officials spent the day role playing a scenario in which a highly organised and powerful group were attacking the Capitol to prevent the certification of the 2024 elections.

This was an exercise or “game” to better understand the seriousness of the threat.”

The origin of the game was a letter to The Washington Post in December 2021 by three retired military generals who said they were increasingly concerned about the possibility of such an attack, that it might involve enlisted soldiers, and that the military should prepare for such an insurrection They recommended a “war game” in which the scenario was tested.

The game was put together by Vet Voice Foundation, which is a group of former US military personnel who think that the government “is not doing enough to root out white supremacists and far-right militants in their own ranks.”

(Quotes come from the film. I think I have transcribed them correctly from my notes.)

Responding to a scenario

The way a game like this works is that individuals play roles and respond to an unfolding scenario. They have a brief about their role, and they often bring similar experience from their career history to their game role. So here, for example, President Hotham is played by the two-term Montana Governor Steve Bullock, the National Security Adviser by someone who has worked for the Department of Homeland Security, and so on.

(Steve Bullock as ‘President Holtham’ Credit: Wolfgang Held. Source: Electronic Press Kit)

The scenario here has upped the stakes on the 2021 insurrection: what happens, it asked, in a similar situation if members of the US military break their oath to uphold the Constitution?2 A Senator who took part in the game described it as “coup prevention 101.” It’s set on January 6th 2025.

The game is set up in the manner of a war game: the Blue Team are the President and his team, trying to maintain control, and the Red Cell are the adversary, the insurgents trying to prevent the certification of the incoming President by Congress. The White Cell is the control room, where the game’s designer and producer are watching events unfold—and feeding developments into the game. The game runs live for six hours, with a big countdown clock on the wall.

The scenario starts with several thousand protestors on the streets of Washington DC representing a (fictional) organisation called The Order of Columbus, which is a more structured and better organised version of existing far-right organisations such as the Oath Keepers and the Patriot Boys. Around 120 members of the National Guard who are also members of The Order of Columbus have sided with the insurgents. There are reports of disturbances in a number of other cities, such as Phoenix, Arizona.

’Soft simulation’

In other words, this is a “soft simulation”, in which a group of people are put into role, sometimes with some private information about how to play it, and draw on their knowledge and expertise to play out a situation as it unfolds in front of them.3 The skill of the designer (here, Benjamin Gadd) and the producer (Janessa Goldbeck) is two fold. The first is to have some game points where things get tougher; the second is to respond to evolving events in a way that is credible.

Over the years, I have designed some soft simulations and run them, though none at this scale, or this budget, or with people this senior. I’ve used them to test scenarios, to imagine the future of the BBC, to understand how a market might respond to regulation, and on one occasion to test the media response of an oil company in the event of a North Sea oil disaster.

There are some tricks. One is that you know when you design the game that some things are likely to happen regardless of what the players do. In the case of the Washington Game, for example, a serving senior military officer says (through the media) that the President is not legitimate and that soldiers should give their allegiance to the losing candidate.

Similarly, the game story has protestors in another American state take control of the State Capitol building, along with hostages. You can write these in because, in effect, they are independent of the actors in the game.

The design of the ‘media’ in the game is also important. The Washington game had a compelling news anchor whose inserts increased the stakes at critical points. I couldn’t tell from the film whether they had prerecorded these, but it seemed likely. As news reports came in of (small numbers of) military defections, one news summary said,

If you are just joining us, the military is split and it is unclear if the Commander in Chief [i.e. The President] is still in control of the country’s armed forces.’

This felt like a design escalation to me. The news coverage up to that point had been more like CNN, but this was a Fox News moment.

In a political story like this, the President and his staff are also making statements and announcements to the media, and social media also creates a lot of gameplay flex, since it’s effectively under the control of the actors in the simulation.

The Red Cell

The blue team/red team model isn’t the only possible design for a simulation, although it is one that is familiar to the military, and it works well for this specific scenario. If you’re going to run this design of game you need your opposition to be good. In War Game they were very good, effectively running a social media disinformation system, on one occasion “flooding the zone”, in Steve Bannon’s phrase, with videos that were (in game terms) half-fake and half-true.

When the Secretary of State issued a tough reprimand to National Guardsmen who had broken their command chain and sided with the insurgents, the leader of the red cell, Kris Goldsmith, immediately sent out a social media message saying that ‘the fake Secretary of State’ didn’t have the authority to order the National Guardsmen around.

Goldsmith is an army veteran who had served in Iraq, and was discharged after trying to kill himself on his return, which meant in turn that he lost his post-service education grant. He’s seen briefly in the documentary testifying to Congress about his time in Iraq. He has clearly gone through a dark time in his past.

”I do understand the insurgents, I understand what led them down that path. Because I was there when I came back from Iraq.

The game’s producer, Janessa Goldbeck, also a member of the Vet Voice Foundation, is a former Marine, but not maybe typical. She was part of the first intake after out-gay people were allowed to serve. She has personal reasons for being involved:

My dad started talking about QAnon, and this made no sense, because he is a decent and intelligent person.

Behaving differently

One of the reasons that you use simulations rather than other dialogue processes to explore the future is that people behave differently, especially when under pressure, even when they’re only in role. You get different system insights. Some of this is about single loop learning and double loop learning—using Chris Argyris’ framing. No matter how much we believe we’ll be reflective, when under pressure we tend to default to simpler and more habitual modes of action.

(Inside the Presidential ‘war room’. (L to R) Simulation note taker, Elizabeth Neumann, Lou Caldera, Wes Clark, Steve Bullock, Linda Singh, Gwen Camp, David Priess, Pete Strzok. Credit: Thorsten Thielow. Source: Electronic Press Kit)

The documentary doesn’t include any of the insights from the debrief, perhaps deliberately, but it’s pretty clear what the main insights are.

The first is that the insurgents are desperate for the state to escalate the violence as it tries to regain control of the streets. As Kris Goldsmith says:

The Red Cell has to encourage the American government to massively over-react.

There are several times during the simulation where the government seems about to do this, but it steps back on each occasion.

There are several forms of over-reaction. ‘President Hotham’ is urged to shut the bridges across the Potomac so that the insurgents can’t bring in support, but decides against:

I’m not ready to shut down the city yet.

He’s also advised to tap the phone of his defeated opponent, Governor Strickland, who is of course agitating. He decides against, because someone will find out, sooner or later, and this would be politically damaging.

Escalation

The biggest decision, though, is whether to use the different forms of escalation available in which federal troops can support state National Guards. The first is to ‘federalise’ the National Guard at a state level, bringing state troops under the Department of Defense command structure. The second is to use the Insurrection Act, in which federal troops are used for policing.4

Both have the risk of making it appear as if the government has lost control of the streets. The President’s ‘war room’ start talking about the Insurrection Act very early in the simulation, and even prepare the ground, but (spoilers) don’t ever invoke it.

Finally, one note on the asymmetric nature of communications. The Red Cell is small and responsive; the Blue Team often seems overloaded with information. There’s a moment where one of the Red Cell team says,

Look at how much disinformation we’re putting out, and they’re not countering it. They’re just focussing on what’s happening on the streets.

There’s probably an insight there about ‘seeing like a state’, but it’s also true that it takes some time for this sprawling Blue Team to start functioning. It’s as if we’re watching them work through all the stages from forming to performing in front of our eyes. It takes them a while to be able to work at the right clock speed.5

Eventually, they realise that their focus needs to be on getting the Certification done (this is the purpose of this game, after all), and (spoilers again) manage to reconvene Congress.

And sometimes games have fine moments in them. As ‘President Holtham’ grabs the notes prepared for his address to the nation at the end of the game, about the purpose of politics and the value of the Constitution, and heads quickly for the lectern, I feared for the quality of his speech. But the speech he gives is stirring and effective. It certainly moves some of the participants. You realise that you don’t get to be the Governor of Montana without quite a lot of political skills.

Update: coal

On Tuesday I wrote about the closure of the last coal-fired power station in Britain, which makes the UK the first country in the G7 to end coal-powered electricity generation, if only the 14th in the OECD group of countries. I should also have credited Jeremy Williams’ essential Earthbound Report as the tip for this news.

Anyway, BBC Nottingham posted a short video of the moment on Monday afternoon when the Ratcliffe-on-Sea power station was switched off. It says something evocative about the nature of skilled work:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/videos/c98ye7ewwlwo

(Source: BBC Nottingham, still, taken from video)

j2t#606

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

I thought it was worth looking at how they described themselves: “Our books are short—novella-length, and readable in a few hours—but ambitious. They offer new ways of looking at and understanding the major issues of our time.”

One in five of those who took place in the insurrection on 6 January 2025 had served in the military.

Heidi Heitkamp, a former North Dakota Senator who plays the President’s special adviser, seemed to have an instruction to be hawkish early on and then back away from these positions later on, for example. But that might just have been her take on the unfolding situation.

It was last deployed by President Bush in 1992 in the face of rioting in Los Angeles.

This also happened in my oil company simulation. The media team was so busy trying to agree a statement that they missed the lunchtime news, which therefore had to report that “the company has still not commented on the news of the explosions.”