1 October 2024. Coal | Non-violence

The end of coal-fired electricity in Britain // Organising for non-violence [#605]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The end of coal-fired electricity in Britain

Yesterday saw the closure of the last coal-fired power station in Britain, and it turns out that this is a big deal, not just for Britain but internationally as well. There has been assorted recent coverage, above and beyond the mainstream news, and I’m going to try to pull some of that together here. Decommissioning of the plant will take two years, and a clean energy plant is planned for the site after that.

It’s a big deal internationally because Britain is the first of the G7 countries to eliminate coal power, and Carbon Brief has a very long explainer of the issues involved.

They start with a little context. Britain was also the first country to introduce coal-fired power stations, in Holborn, London, in 1882. Since then the country’s coal plants have burned through 6.4 million tonnes of coal, which is more coal than most countries have produced in total. It’s a reminder, as David Edgerton notes in one of his books, that at the beginning of the 20th century Britain’s vast coal production made it“the Saudi Arabia of 1900”.

Staying with this historical note for a moment, the Carbon Briefauthors, Molly Lempriere and Simon Evans, point out that the closure will mean that coal consumption in Britain will fall to levels not seen since the 17th century.

There are, they say, four reasons why Britain has reached this landmark:

Building alternative sources of electricity generation, in sufficient quantities to meet and then exceed electricity demand growth.

Stopping the construction of new coal-fired power plants.

Internalising externalities, via policies and regulations, so that coal plants face the cost of the air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions they generate.

Sending clear political signals that market actors can work towards.

Their point here is that to a large extent these options are also available in other richer countries. There’s nothing special about the British energy mix:

The UK’s experience... demonstrates that rapid coal phaseouts are possible – and could be replicated internationally.

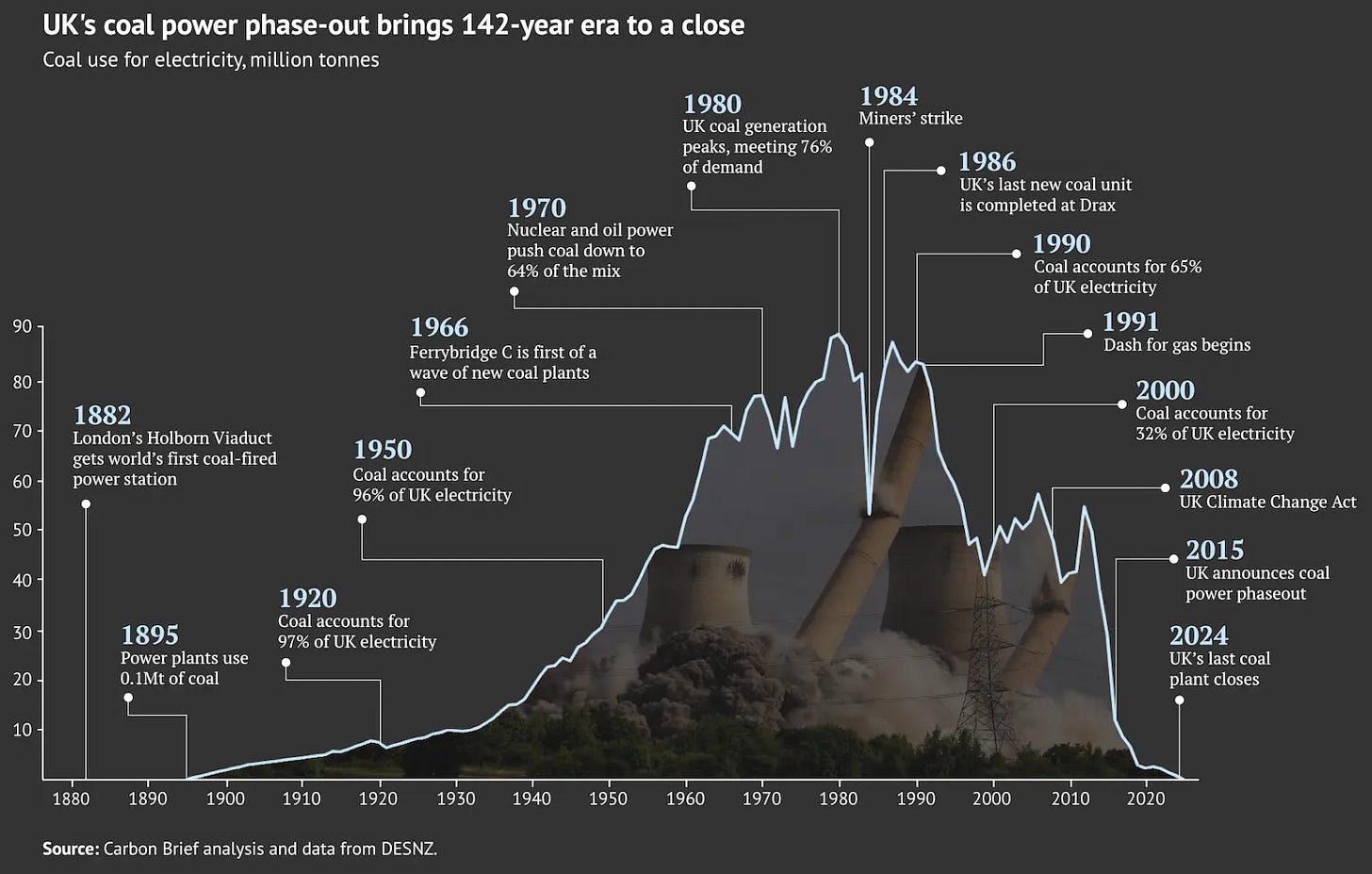

In fact, there’s a striking chart in the article showing the rise and fall of coal as an energy source.

(Source: Carbon Brief)

One of the striking things about this chart is the relative speed of the decline in coal: a rapid fall from 1991, when coal accounted for 65% of British electricity generation, as electricity producers switched to gas, followed by a period where demand plateaued after 2000–when coal’s share of generation had fallen to 32%.

The second fall follows the passing of UK’s Climate Change Act in 2008.

The story of the factors that changed the landscape is a complex one, but it includes a series of regulatory and policy initiatives. These included the 2000 report by the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, with a proposed long-term emissions reduction target, which eventually led to the UK Climate Change Act in 2008.

The development of an EU carbon trading market, along with new rules on air pollution, is also relevant. Britain’s coal fleet was ageing at the time, and it proved to be too expensive to upgrade these old power stations to meet new pollution rules.

And so is protest, notably that by the ‘Kingsnorth Six’, who scaled the towers of an existing coal-powered station to demonstrate against a proposed new coal power station on the site. The following year the Labour government’s energy and climate secretary, Ed Miliband, announced that no new coal power stations would be built in Britain without CCS technology—Carbon Capture and Storage.

The final elements in this story is the rapid increase in the provision of renewables as their cost has fallen, the slow development of CCS, which is still not much more than a demonstrator technology, and a decline in energy demand through a combination of falling demand, from greater energy efficiency and the offshoring of some energy-intensive production.

Dr Simon Cran-McGreehin of the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit [ECIU], told Carbon Brief that coal generation had become “uncompetitive” through a

combination of air-pollution rules, the cost of CCS and carbon pricing has made ongoing coal generation “uncompetitive”. He says: “Ongoing coal power simply isn’t an option, as it would have such high costs…that it would be uncompetitive with even gas and nuclear, let alone new renewables.”

Another valuable chart in the Carbon Brief article shows the changing electricity generation mix over the last 100 years—from 1920, when it was negligible, to 2020.

(Source: Carbon Brief)

The critical factor here is the rise of renewables. Sean Rai-Roche of E3G underlined this point to the Carbon Brief journalists:

“Crucially, coal hasn’t been replaced by other fossil fuels, gas generation fell from 46% in 2010 to 32% in 2023... So, on a gigawatt basis, we’ve replaced the ‘~firm~’ coal capacity with gas, but on a gigawatt hour basis – which is what matters to emissions – we stopped using as much [of either] coal or gas because of the renewables on the system.”

The share of gas in electricity generation is projected to fall sharply this year as renewables’ share continues to rise.

One of the relevant points here is that taking coal-fired electricity out of the system quite rapidly, and replacing it with renewables, hasn’t led to power cuts or black-outs, although these have been predicted regularly over the last decade or so.

The energy journalist Jess Ralston included a telling set of these headlines in a Twitter thread.

(Source: Jess Ralston/Twitter).

There’s perhaps some excuse for some of the earlier scare stories. I facilitated a workshop on new energy systems in 2010 and was told by one of the leading experts on the National Grid—which, of course, always has to balance demand and supply—that we didn’t yet know if the Grid would remain stable as the proportion of renewables increased.

But as Ralston points out in her thread,

But the reality is 𝙚𝙭𝙩𝙧𝙚𝙢𝙚 𝙬𝙚𝙖𝙩𝙝𝙚𝙧 is behind most power cuts & the last severe UK blackout was caused by lightning hitting the transmission infrastructure and causing a gas power plant & windfarm to go offline.

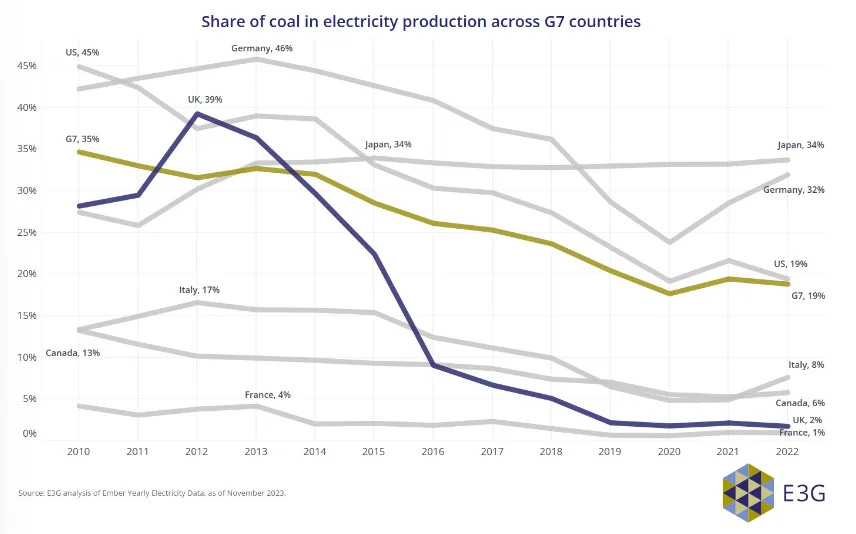

E3G’s backgrounder on the closure of Ratcliffe-on-Sea (which is pithier if you just want the policy points) has a useful chart showing the international comparisons over time on coal powered generation.

(Source: E3G analysis)

Globally there are still something like 9,000 coal fired power stations worldwide, and according to the Fatih Birol of the International Energy Agency they account for one-third of global emissions. On the other hand a number of other countries have already retired coal from their power mix—including Belgium, Sweden, Austria and Portugal.

The G7 has, at least, agreed to end the use of “unabated coal” (i.e. coal powered generation must use carbon capture tecnologies) by 2035, although to me that seems like foot-dragging.1 On the upside, across OECD countries coal-generated electricity as a share of the total has now fallen to half of its peak.

As for the UK, if it is to hit its target of clean energy production by 2030, it will need to phase out gas twice as quickly as it has phased out coal. In other words, we can’t take our foot off the gas.

(Source: Carbon Brief)

2: Organising for non-violence

Peter Levine is the Professor of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Tufts University's Tisch College of Civic Life, and he has just published an intriguing post on the value of non-violence as a political strategy, based on the Frontiers of Democracy conference, held at the college last week:

Our theme was nonviolence, because I believe that we are entering a new phase of political violence, with a real possibility that the presidency will be an instigator in 2025. I argue that we must develop skills, strategies, coalitions, organizations, and plans for large-scale, broad-based nonviolent resistance.

My thanks to Ian Christie for alerting me to it.

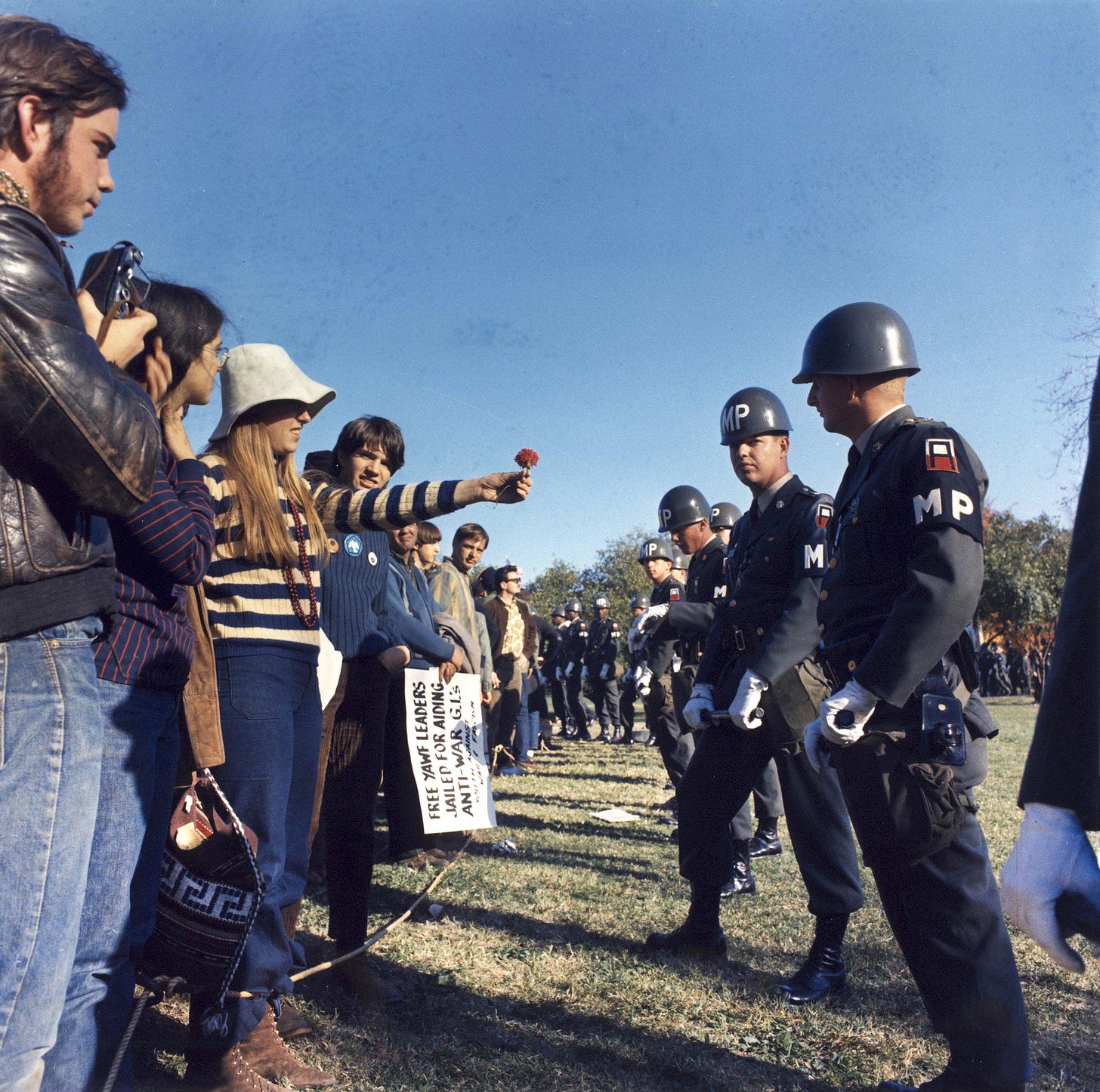

(Vietnam War protest, 1967. Photo: S.Sgt. Albert R. Simpson, public domain)

Levine starts the post by acknowledging the influence of Reverend James Lawson, who had died the previous week at the age of 95, whom Levine had interviewed in 2022 (57 minutes, see below for a link to this). The article starts by reiterating some of the points Lawson made about non-violence:

Nonviolence is not the absence of violence–not a decision to refrain from using violent methods. It is a powerful alternative, with a record of success... nonviolent civil resistance movements often win.

Protest is not the essence of nonviolent resistance... most of a movement’s impact comes from boycotts, strikes, get-out-the-vote, popular education, work inside institutions, and so on. In the interview, Rev. Lawson says, “The march may the weakest tactic, not the strongest.”

Americans have by no means forgotten nonviolent strategies... BLM has been the largest nonviolent movement in US history and has been associated with a lower amount of collateral violence than the classic Civil Rights Movement.

In his reflections below, he adds some further commentary. The first is that non-violence is the only way that most people are willing to engage in political movements, certainly if violence is not endemic:

The only way to build really broad-based movements (at least outside of dictatorships and civil wars) is to be nonviolent.

And thinking of Vaclav Havel’s famous essay “The Power of the Powerless”, it may also be the only way to build broad-based movements in dictatorships as well.

Second, non-violence (like all political action) requires organisation:

One thing we learned from the #Resistance in 2016 is that Americans have good skills for expressing their views and finding allies, but underdeveloped skills for building large and accountable organizations and coalitions.

Levine is exercised, of course, by what might happen if Trump wins the Presidential election in November. He anticipates that there might be quite widespread opposition, but that it may not be well-represented by the Democratic party:

Much of the opposition will arise in civil society, in faith communities, perhaps in labor, in media and culture, on the far left, among some conservatives, and perhaps among some businesses. Only some opponents will appreciate the Democratic Party or want to use strategies that involve legislation and elections. Leaders will arise in various sectors and constituencies, and they may or may not cohere.

This opens up a discussion of political leadership. Levine thinks that “apex leadership” is over-rated—its value is mostly symbolic.

Still, people like you and me will have to decide what to do in the absence of a widely recognized leader, unless one surprises us by emerging quickly... Who will invite representatives of the aligned small organizations in a given state to a statewide convention? How will that convention make decisions?

He also suspects that in the aftermath of a Trump victory there will be “recriminations and divisions.” (I think he might be imagining here scenarios where Trump loses the popular vote but wins the electoral college, or where a Trump victory is enabled by different forms of manipulation of the vaote):

Regular Democrats will be furious that radicals and others voted for third-party candidates, stayed home or (at best) failed to make the case for the Democratic ticket. Many others will be equally angry at the Democratic Party, for a variety of reasons.

He concludes the piece by mentioning some recent history books he has been reading: Jonathan Healey’s The Blazing World, which he recommends, and David Cannadine’s Victorious Century, about Britain from 1800-1906.

That’s quite a lot of British history, and Levine offers the right caveats about how much you can learn from history. All the same, he does draw some conclusions from this:

Large public majorities have a decent chance of getting their way, even when the political system is highly unequal.

Elite minorities have a good chance of dominating, if they control the levers of power.

Activated minorities that lack power may attract attention and leave their mark on history, but they will fail unless they grow into majorities.

The second one of these has echoes in Peter Turchin’s analysis of elite power—elites can maintain power for a long time as long as they don’t split. And the third seems to me to reflect the conclusions that Rupert Read came to when he set up the Climate Majority project.

Trump, he says, “he will represent a minority with his hands of the levers of power.”

But building a majority that is not fragmented requires quites a high degree of political and organisational skills and values. These include,

a genuine desire to listen across differences, a willingness to choose winnable battles, and a nuts-and-bolts understanding of nonviolent organizing.

Remembering Kris Kristofferson

I found myself surprisingly affected by the death of the singer and actor Kris Kristofferson at the age of 88. As a musician, of course, he wrote some classic songs: ‘Me And Bobby McGee’, ‘Help Me Make It Through The Night’, ‘Sunday Mornin’ Coming Down’. But in The Guardian, the film critic Peter Bradshaw reminds us that he not sung a single note he would still be remembered for a long and reasonably significant Hollywood career.

Kristofferson was perhaps unlucky to have been involved in Heaven’s Gate, Michael Cimino’s sprawling epic about the John County Wars, which bankrupted the studio and damaged reputations undeservedly. The film partly suffered from bad timing—a story about the violence of the powerful and the rich released just after the election of Ronald Reagan. But in some ways his part, of the Harvard-educated upper class sheriff who takes the side of the immigrant homesteaders against the cattle barons, captured a bit of Kristofferson as well, the Oxford Rhodes scholar who took on dirty jobs when he left college so he would understand what life was like.

I was looking for the scene where he is upbraided in a gentleman’s club in the East for trying to protect the homesteaders, but YouTube doesn’t seem to have it. So here instead is the lovely waltz with his co-star Isabel Huppert (3’50”). David Mansfield, who wrote the music, is the violin player.

j2t#605

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Maybe they hope that CCS will be viable at scale by then.