4 July 2023. Climate | Sewage

Mapping cascading climate risks // A modest proposal to rebuild Britain’s sewage infrastructure. [#474]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Mapping cascading climate risks

I went last week to the launch in the UK of the CASCADES project, an EU-funded initiative that seeks to identify the scale and extent of cascading risks arising from climate impacts. They have a relatively sophisticated methodology to do this, but there’s a straightforward example in the little (3 minute) animation they use to introduce the concept.

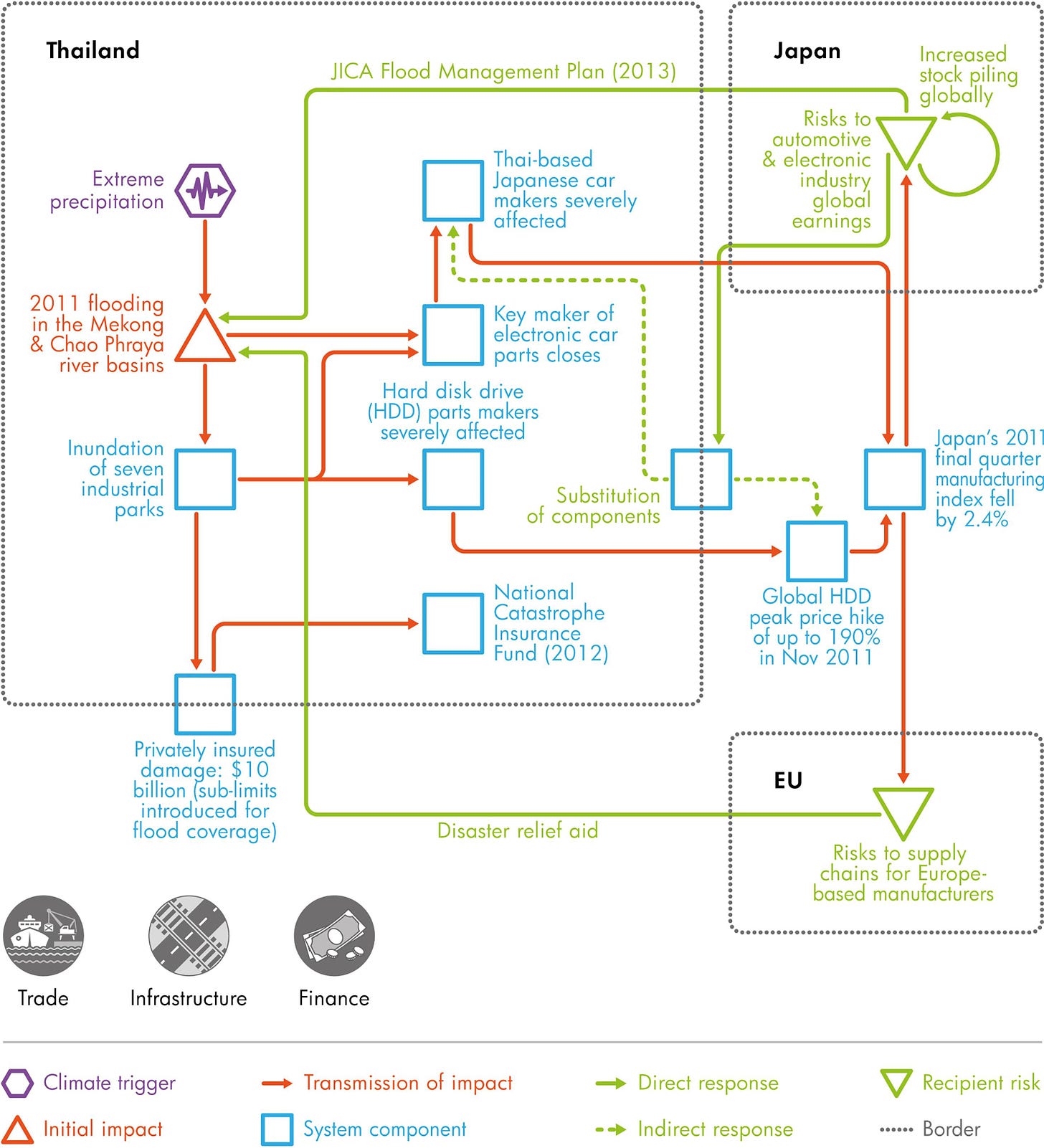

The 2011 tsunami in Thailand inundated many manufacturing plants, making parts for the automotive and electronics industries, that had been built near the coast to reduce transport/export costs, by companies that didn’t anticipate flooding risk. The result of this was that the Japanese manufacturing output declined during the rest of the year.

The CASCADES youtube channel also has a video from a ‘simulation’ workshop (2 minutes 30), based on a mine being taken over by an African government because the mining company hadn’t kept to its agreements, that plays through some of the ideas of cascading risks.

There’s an open-access academic paper at the journal Global Environmental Change that goes through this more formally, explaining the method and the mapping that they have developed.

The critical innovation here is that the model looks at cross-border risk (it may seem surprising that this wasn’t done previously, but they say that there has only been a limited amount of such work.)

So here’s a visualisation of that from the paper.

(Source: Carter et al, ‘A conceptual framework for cross-border impacts of climate change’, Global Environmental Change, 2021)

And here’s a simple example, based on heavy rain and flooding:

(Source: Carter et al, ‘A conceptual framework for cross-border impacts of climate change’, Global Environmental Change, 2021)

The red/orange line shows the impacts of the rain and the flooding; the green lines show the mitigation. The key in the example below spells out the key to the shapes.

There is a couple of reasons given in the paper for wanting to understand such risksbetter. The first is that

climate change has developed into an important scientific and policy field in its own right. As a result there is a need for structure and clarity to identify the mechanisms via which climate change creates risks for society.

The second is that responding to such risks involves identifying the transmission mechanisms in a structured way, creating a common language to do this for researchers and policy makers:

The relative neglect of cross-border impacts in national and international policy-making may increase potential risks and the costs of inaction. However, the design of actionable adaptation strategies to address such risks calls for a proper conceptualisation of the processes, scales and dynamics involved.

To which I might add: they are already getting bigger, and they will continue to get bigger.

The paper goes through the framework that the CASCADES project has created in some detail, but I’m going to borrow here from the description in the abstract, since it’s a concise description, and break it into its component parts, starting with the trigger:

The conceptual framework distinguishes an initial impact that is caused by a climate trigger within a specific region.

Transmission mechanisms, as mentioned above, come in two parts: the impact transmission mechanism and the response transmission mechanism:

Downstream consequences of that impact propagate through an impact transmission system while adaptation responses to deal with the impact propagate through a response transmission system.

The framework then breaks out these into different kinds of cross-border impacts, as well as

the scales and dynamics of impact transmission, the targets and dynamics of responses and the socio-economic and environmental context that also encompasses factors and processes unrelated to climate change.

From there, it’s possible to tease out different types of causal relationships. By way of a worked example, here’s the busier worked example of the Thai tsunami discussed above:

(Source: Carter et al, ‘A conceptual framework for cross-border impacts of climate change’, Global Environmental Change, 2021)

I found the panel discussion at Chatham House a bit frustrating, but I think that is because two of the panellists were diplomats from the UK and the EU, and everyone that they spoke about was wrapped up in that tone and syntax that diplomats in the Global North have perfected, the soft bat, the dead air, which in the meeting sounded like this:

“we agree this is important, and we agree that something should be done, but we’re going to have to go away and agree everything with everyone before we can actually do anything at all.”

(I’m not going to name them: it wouldn’t have mattered if other people from the UK or the EU had been in the room.)

I could understand the frustration of Ambassador Sacko of the African Union, who reminded them that climate pollution was coming from the North, so it was the Global North that was causing climate cascades in Africa. I’m not sure I caught the quote exactly right in my notes, but at one point I think she said,

We can still be talking about this at COP1000.

Ruth Townend of Chatham House summarised the recommendations from the project, which are, in summary:

All regions, countries and continents need to address cascades

Leverage points will influence the system

Improve resilience through mitigation (most cost-effective) and being transparent (“countries need to be honest about cascades in which their countries are implicated”

Reform institutional governance, so you understand the cascading risks you are implicated in, and allocate ownership of them

Make trade and financial flows work for resilience, not against it: and shift the finance paradigm from efficience to resilience. (Good luck with that, I thought).

Prepare society to play a part in cascade management, and

Champion appropriate global governance that’s fit for a world of cascades.

One of the recommendations was that the cost of climate change should be priced. Looking at the models, and listening to the presentations, it made me think that the cascading risks model might make it easier to make the case for more effective climate action in the Global North, because it makes the costs and impacts in the North more visible.

Chatting to some people afterwards, they weren’t so sure. They didn’t think that the economics of climate change was going to be the right mechanism to change behaviour. They might be right about behaviour. But since economics is still, sadly, the dominant language of policy-makers, it might shift some policy thinking.

2: A modest proposal to rebuild Britain’s sewage infrastructure

I hadn’t meant to come back to water and sewage yet again—to some extent this is just a British problem, and I try to stay away from those on Just Two Things.

But I spent some of the weekend thinking some more about how to solve Britain’s sewage problem, having written on Friday about Richard Murphy’s suggestion that the investment needed might come from Britain’s savings pool. I’ll come back to some of the detail of that later on in this post.

In short, though, this is a modest proposal for a public interest company that acts as a critical infrastructure agency that has responsibility for Britain’s sewage network. It has the authority to raise money to fix it from the savings and pensions market, and charge the water companies for services as well.

Let’s just work through the problem for a moment, which has, lately, been caused by Britain’s doctrinaire decision in the 1980s to privatise water provision even though water is a “natural monopoly”. You’re not going to have two competing sets of pipes going in and out of a building.

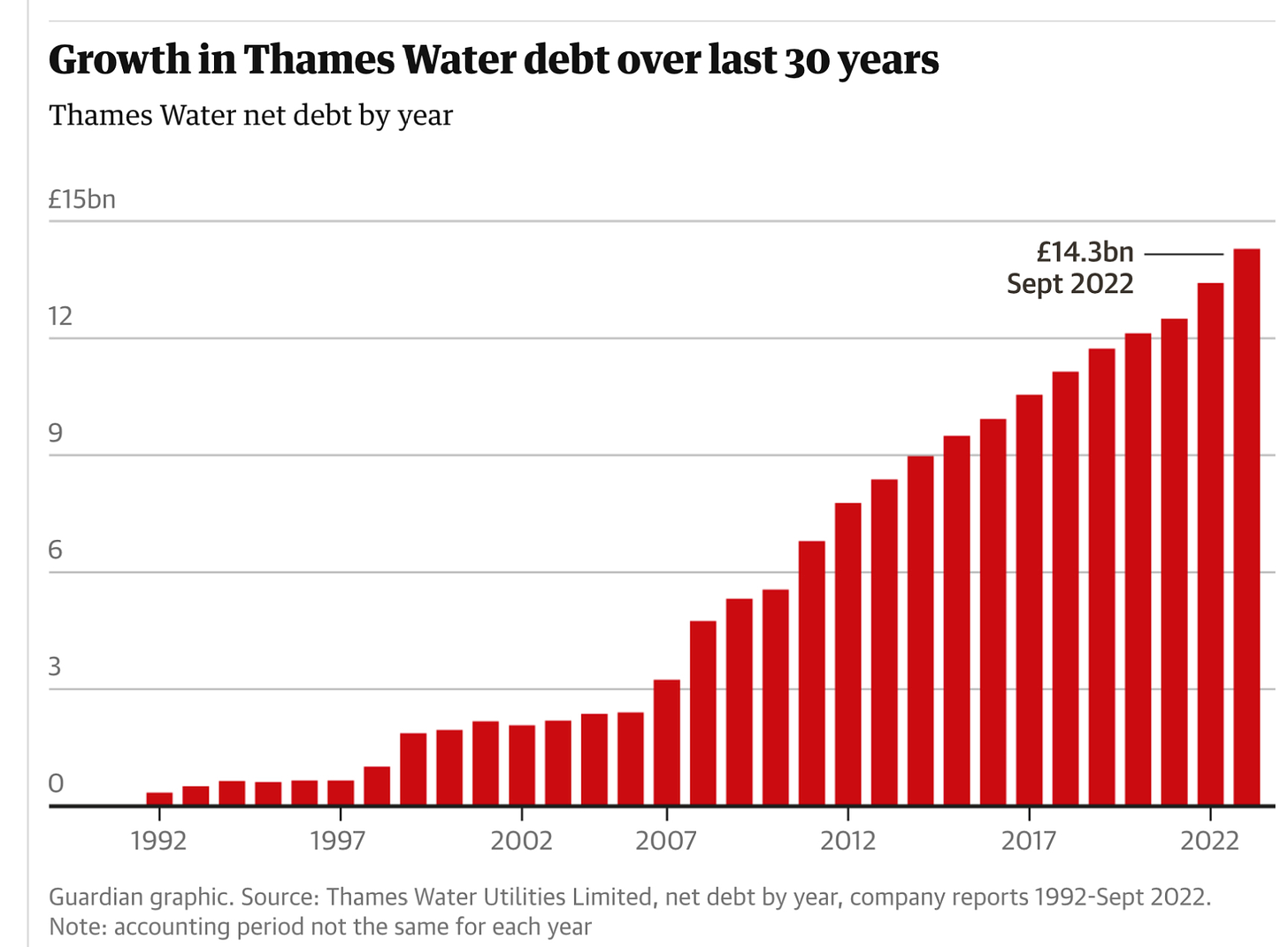

It turns out that the civil service’s finest minds in the Treasury (UK’s Finance Department) hadn’t really red-teamed this decision. At the time of privatisation (the legislation was passed in 1989), the government wiped the debt off the existing businesses.

The new buyers saw the opportunity to do some financial engineering, so they loaded the businesses with debt, paid the interest payments from the water companies’ steady revenues, and used the money to pay their shareholders vast dividends.

(Source: The Guardian)

I’m labouring this point slightly because one of the principles of systems thinking is Paul Batalden’s observation that

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.”

And we must conclude that the British privatised water system is perfectly designed to funnel vast dividends to its shareholders—and to have legal and regulatory arguments with the regulator—rather than managing water and sewage systems in a cost- and environmentally-effective way for its customers.

This is point 1 of the diagnosis.

Point 2 is that the amount needed to deal with the situation properly is vast. I discussed this on Friday, but it’s £260 billion, to do it properly. Readers who have been following this story will notice that this is a lot more than the £10 billion that the water companies have promised to spend (using money from consumer bills) to try to address the problem, and also more than the £56 billion that the government thought might actually be needed to fix the problem.1

Point 3 is that a low wage, low productivity economy such as Britain which has seen public assets scraped to the bone over the last 13 years doesn’t have that much scope for increasing the tax take — and that whatever scope it did have would likely be absorbed by even more important public services that appear to close to the point of collapse because of austerity—like the health service and the education system.

Point 4 is that investment against rebuilding infrastructure can always be supported by an economy, provided it can find the money in the first place, because rebuilding infrastructure generates its own economic activity that increases the tax base, and so on.

So that’s the summary: the current water system is broken; it takes a lot of money to fix it; the British economy is both fragile and stretched bare; but the proposition of investing in infrastructure is attractive if it can find the money.

One of the things that Bill Sharpe talks about in terms of building new systems is that it’s better to look for points of abundance (an ecological frame) than think about scarcity (an economics frame).

This was the reason that I liked Richard Murphy’s suggestion that Britain’s savings-based ISAs might be a way to pay for rebuilding sewage systems, since the government already has a model under which savers who hold an ISA for a number of years get a tax break for doing this.

That’s also clearly not the only way to pay for it. As I wrote here a few weeks ago, there is also a host of long-term investors, such as pension funds, who need long term investment vehicles that match their time-frames. One of the several ways in which the current financialised system is broken is because short-run finance actors insert themselves between utilities, which would normally look for long-term stability, and pension funds, that look for long-term investments.

But: no-one will trust the current private water companies, ever again, and quite rightly. They have shown over and over again that they have no interest in the public interest. Galbraith’s phrase about private affluence and public squalor comes to mind. It’s worth quoting here quickly from the House of Lords report:

It is clear that in the past, a number of water companies have been overly focused on maximising financial returns, including by increasing debt levels, at the expense of operational performance and protecting the environment.

So—the sewage infrastructure needs to be in the hand of an organisation that has the public interest at its heart, but one that also can behave as a commercial actor, issuing bonds or other savings vehicles.

The thing is: the UK already has organisations like this that look after critical infrastructure for strategically important sectors. It’s not a completely new model. The Highways Agency manages the Strategic Road Network, although because that’s almost entirely paid for from tax revenues (and not ‘road tax’), the business side is missing. Network Rail, after a (literally) dangerous period in private hands, is now a public agency that runs the rail network and has business relationships with the train companies.

This seems like an obvious idea, and I feel sure that someone else must have had it already, but some light googling didn’t turn up think tanks or policy organisations suggesting it. But in general: this would be a public interest company of some kind that looked after critical sewage infrastructure.

I realise that there are complications. I’m not sure if it needs to include the piped water infrastructure as well (given the level of leaks, maybe it does). Transferring the assets from the water companies requires a negotiation, although if you wanted to play hardball, you could threaten to put them out of business by requiring them to meet already agreed proper (and more expensive) regulatory standards.

The infrastructure itself is on their balance sheets, so taking it away from them might also make them technically insolvent. (Richard Murphy, whose blog post set me off down this road, might have a view on this.) The Sewage Infrastructure Trust would almost certainly need to be able to charge the water companies for services as well. And so on.

For the moment: let’s just take this as a speculative modest proposal. I’d love to hear from anyone who has seen something along these lines somewhere else.

j2t#474

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The £10 billion figure, which is pitiful, seems designed to ensure that the water companies aren’t bankrupted, or, given the assumption that consumers will pay, that bills don’t go too high. The £56 billion figure seems to be predicated on the idea that some sewage outflow into rivers, even environmentally sensitive rivers, is still OK.