4 April 2024. Culture | AI

Distraction is eating culture for breakfast, maybe // Cautionary notes about AI [#557]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Distraction is eating culture for breakfast, maybe

The music writer Ted Gioia has a long article on his newsletter The Honest Broker in which he talks about the state of culture in 2024. He’s quite pessimistic.

Versions of this schematic appear throughout the piece: this is the second iteration.

(Source: Ted Gioia)

To the left, the notion that art is being gobbled up by entertainment. He doesn’t dwell on this, and it’s a broadly accurate description of the relationship between art and entertainment in the age of mass media, allowing for the fact that using these two terms in this uncomplicated way obliterates a lot of cultural nuance.

Art, if you like, is the avant-garde of entertainment, and entertainment needs it desperately to keep refreshing itself. (I’m reminded of a description of genre that I came across 30 years ago: “Always different; always the same”. The difference comes from the innovation; the innovation usually comes from art.)

Gioia doesn’t see it quite like that:

Until recently, the entertainment industry has been on a growth tear—so much so, that anything artsy or indie or alternative got squeezed as collateral damage.

But the entertainment industry seems to have got stuck. He has a whole group of scan hits here. The Hollywood studios are struggling1 ; there was a turndown in the number of new US TV series (albeit after a decade in which the number of new series jumped from 216 to 516, which sounds like a saturated market to me); the music industry sees more value in Michael Jackson’s back catalogue than in new artists.

But this discussion probably doesn’t matter too much here because he’s much more interested in what’s happening on the right hand side of the schematic:

The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction. Or call it scrolling or swiping or wasting time or whatever you want. But it’s not art or entertainment, just ceaseless activity. The key is that each stimulus only lasts a few seconds, and must be repeated.

In other words, he argues, “everything is getting turned into TikTok”. And because of that, everybody else is copying TikTok. Scrolling is the dominant cultural form of our times. Or something like that.

Gioia thinks that this is not a fad, but something that can potentially go on forever, because it plugs into an addictive brain system, in which the brain releases dopamine in exchange for these bursts of attention, and this makes us feel good, and so we do it again.2 This is a form of addiction.

The article has a helpful diagram to summarise this addictive cycle.

(Source: Ted Gioia.)

So his new model of culture sees distraction as just a stepping stone on the way to addiction. And, in turn, the domination of entertainment by Silicon Valley companies who are only interested in the hits of attention they get from their users:

(Source: Ted Gioia)

The tech platforms aren’t like the Medici in Florence, or those other rich patrons of the arts. They don’t want to find the next Michelangelo or Mozart. They want to create a world of junkies—because they will be the dealers.

So the story he constructs off the back of this is that:

Tech platforms are optimising around scrolling

Their algorithms are designed to do whatever they can to keep you on their platforms

And now they’re busy promoting VR headsets that will make all of this worse

And they already know that all of this is bad for their users:

The tech CEOs know this is harmful, but they do it anyway. A whistleblower released internal documents showing how Instagram use leads to depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. Mark Zuckerberg was told all the disturbing details... But still they push aggressively forward—they don’t want to lose market share to the other dopamine cartel members. And with a special focus on children.

I’ve got time for Ted Gioia, who is one of our more thoughtful cultural writers, but I’ve quite a lot of critiques of this argument. Before I get to those, let me just walk it through to Ted Gioia’s final point: everything is turning into what he calls “dopamine culture”, summarised in a handy chart.

(Source: Ted Gioia)

Some of my critiques come down to a version of Stein’s Law:

‘If something cannot go on forever, it will stop’.

Because at the heart of this argument is a kind of techno-corporate inevitabilism, along the lines of Silicon Valley will always get its own way and we are powerless to stop them.

But when we look at what’s happening around us, everything isn't getting shorter and shorter. Indeed there’s been a more subtle trend going on: short stuff has been getting shorter, but long stuff (movies, TV series) has been getting longer. The audiobooks market, where the typical product in 8-20 hours, continues to grow, as does podcasting. And so on.

Looking just at the bottom line of the diagram above, there are lots of reports that that the “dating market” is moving away from app-based match-making. (Update: Or here, more recently.)

And no matter how many times I look at the VR headset market, they look like a difficult, specialist, sell to a few niche areas, not so much because of the price (which will fall) but because of the intensity of the experience, which requires your obsessively complete attention. It’s not a completely human experience.

Gioia himself, as he goes (much) deeper into the world of dopamine, effectively points to another likely limit on this form of cultural behaviour:

The more addicts rely on these stimuli, the less pleasure they receive. At a certain point, this cycle creates anhedonia—the complete absence of enjoyment in an experience supposedly pursued for pleasure.

There are quite complex arguments about the reasons for the spike in young people’s worsening mental health, but it seems likely that particular forms of mobile phone use are a contributing factor. Even here causality is complicated: it’s at least possible that people with poor mental health are more likely to be heavy users of mobile phone apps, which makes them feel worse.

Either way, there’s more nuance here than Gioia is suggesting, as he constructs a future world in which we are all hooked on fixes of digital soma, especially since the digital version seems decidedly less attractive than Aldous Huxley’s original.

And regulators and legal issues are catching up with the technology companies. People are focussing on their external costs (such as health impacts). Indeed, Gioia’s description above of an industry that knows the harm it creates but presses on anyway looks strikingly like the lawsuits that have been brought in the past against Big Tobacco and Big Oil. Big Tech won’t be immune from this.

Thanks to Ian Christie for the link.

2: Cautionary notes about AI

In a recent edition of the London Review of Books, Paul Taylor reviews a couple of the recent books on the development of Large Language Models and AI. He has some cautionary notes, possibly paywalled, on the continuing development (and speed of development) of the technology.

I’m not going to apologise for continuing to take a sceptical view of this here. Having watched the digital/ICT sector quite closely since 1993, it seems the most credible intellectual position. And in any case, people who have the opposite view have access to every media platform in the world, pretty much, to trumpet their views.

Taylor, by the way, is Professor of Health Informatics at University College, London, and his history in researching AI goes back to the 1980s.

There are two reasons for his caution. The first is about the rate at which you make gains as they become more complex. The second is about cost.

So let’s pick up the point about scaling first:

AI researchers talk about the ‘scaling laws’ that describe the relationship between network size and performance. In 2020 researchers at OpenAI reported experiments on models with between a few hundred and 1.5 billion parameters, trained on datasets ranging from 22 million to 23 billion words. They showed striking relationships between improvements in learning and increases in the size of the dataset, the number of parameters and computing power... The relationships, it is worth stressing, are not exponential: dramatic increases in performance have required dramatic increases in scale. (My emphasis.)

But past performance in these things is not a reliable guide to future improvements:

(T)he curves must level off. To be able to express new facts, language must be to some degree unpredictable, which sets an absolute limit on what a network can learn about it. The OpenAI team... conjectured that the point where this anomaly would arise was a theoretical maximum level of performance, at least for models built using this particular architecture – at around 10 trillion parameters and 10 trillion words. In 2020 these numbers seemed purely theoretical, but current models are getting close (Meta’s Llama 2 was trained on 2.4 trillion words).

And what does seem exponential, here, is the anticipated increase in costs of training larger models:

One estimate from January 2023 suggested that it costs around $300 million to train a trillion-parameter model, but that one with 10 trillion parameters would cost something like $30 billion, running on a million GPUs for two years and requiring more electricity than a nuclear reactor generates. Developers are finding less computationally intensive ways to train networks, and hardware will get cheaper, but not at a rate that will allow the models to scale at the pace of the last few years.

I had to write the numbers out by hand to check them, but, in other words, this 10-fold increase in parameters comes with a 100-fold increase in cost.

Since there’s a live and sometimes over-excited discussion of how AI will affect jobs, it’s worth noting a specific example here in a specific market, picking up from one of the more doomsterish projections of Geoffrey Hinton, described by Taylor as “one of the most influential AI researchers of the last 30 years.”

Eight years ago Hinton suggested that it was no longer worth training radiologists, since AI would be able to interpret medical images within five years. He now concedes he was wrong.

The reason he was wrong is interesting, because it points to some of the more nuanced interpretations of how jobs are affected by technology innovation: not a binary on/off switch, but the gradual evolution of a bundle of tasks (David Autor’s model, which I wrote about in Just Two Things).

(Hinton’s) error was not in his assessment of the way AI would develop, but rather in his failure to appreciate how difficult it would be for companies to translate technical success into products in a highly regulated market, or to understand the way a profession evolves as certain tasks are automated. Of the 692 AI systems that have so far been approved by the FDA for medical use, 531 target radiology, and yet today there are 470 vacancies for radiologists listed on a US job board.

There’s also a useful discussion of the word ‘understand’ in the context of a Large Language Model’, in which it is pretty clear that the word ‘understand’ is probably doing some heavy anthropomorphic lifting for AI’s enthusiasts. Taylor references an interview by Ilya Sutsekever, former Chief Technology Offices at Open AI:

Judea Pearl, a proponent of a different approach to AI, responded to Sutskever’s interview by tweeting a list of things that can make accurate predictions without possessing understanding: Babylonian astronomers, dogs chasing frisbees, probability distributions. We should be genuinely awestruck by what ChatGPT and its competitors are capable of without succumbing to the illusion that this performance means their capacities are similar to ours.

In short, as Taylor suggests, we can be surprised by what ChatGPT is doing without having to credit it with superpowers:

Confronted with computers that can produce fluent essays, instead of being astonished at how powerful they are, it’s possible that we should be surprised that the generation of language that is meaningful to us turns out to be something that can be accomplished without real comprehension.

If you’re interested in the AI discussion, the whole article is worth reading. The books reviewed are The Coming Wave, by Deep Mind founder Mustafa Suleyman, and The Worlds I See, by Fei-Fei Li, a pioneer in large language image processing.

This also allows me to pick up something that Wallace Beary pointed me towards at the listserv of the Association of Professional Futurists.

I’m not going to quote him directly (it’s a private listserv) although his observations broadly touched on the incentive systems created by venture capital finance. Companies that are chasing whatever is ‘hot’ in the VC world at any given time are incentivised to tell what he called “a grandiose story” to get the attention—and money—of the VCs. There may be value there, but it probably won’t be on the scale of the claims being made by start-ups.

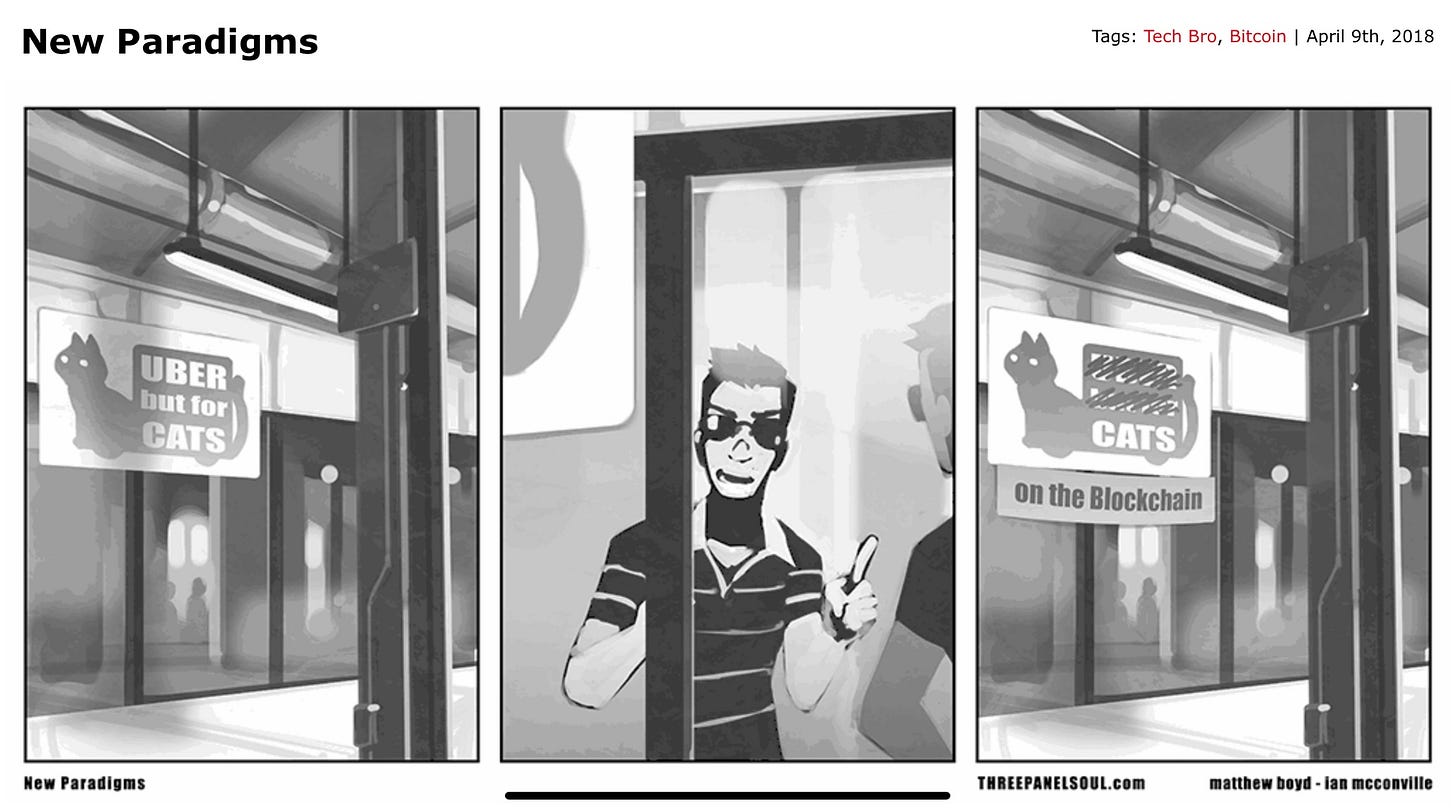

Wallace also shared a couple of priceless cartoons from the comic Three Panel Soul. The first one, from 2018, is called ‘New Paradigms’:

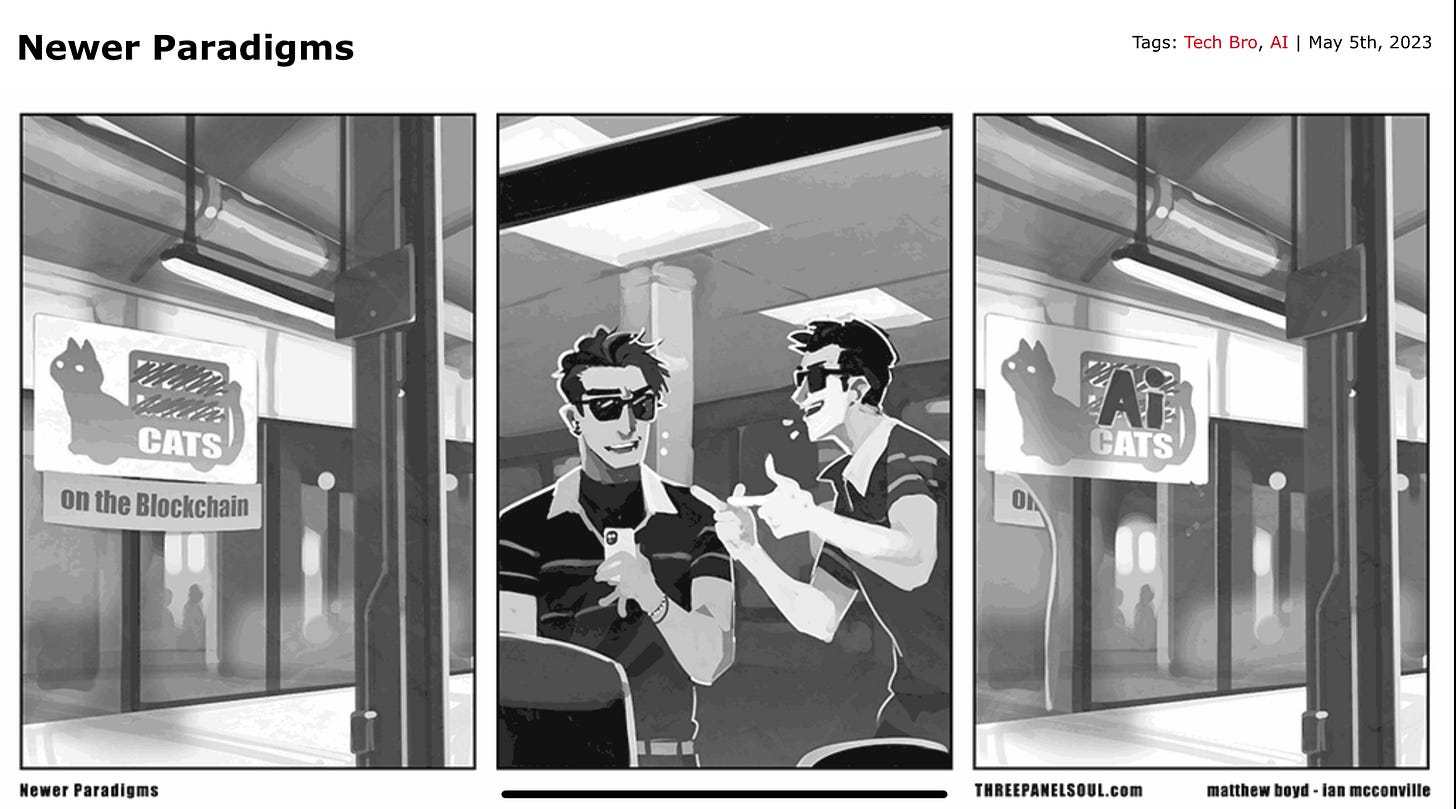

And—from 2023–the sequel, ‘Newer Paradigms’.

OTHER WRITING: Riding London’s cobbles

Over Easter I joined a bike ride across London’s remaining stretches of cobbles—a nod towards the great one-day cycling Classic, Paris-Roubaix, which is held this weekend. There’s a history of London’s road system buried in that, which I wrote about afterwards. Here’s an extract:

Cobbles were put in to London’s streets in the 18th century, because the earthen streets were disappearing into mud and filth (filth meant here quite literally). The cobbles, and the smaller sone setts, solved that problem, but they created another one. They made the streets very noisy, as horseshoes struck on stone, and threw up granite dust as well. Wooden sets replaced them, which solved the noise problem but were treacherous and slippery when wet. Asphalt was first tried out in the City of London in 1869, but horse owners objected.

j2t#557

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

This may be a function of them all trying to build their individual own distribution channels, of course, which there isn’t really enough content to fill.

This is Ted Gioa’s version of this. My son, who has a Neuroscience Masters, tells me that this is a common misunderstanding. Dpamine is released in anticipation of a ‘reward’, not afterwards.