22 January 2024. AI and jobs | Poetry

The IMF’s latest AI and jobs report makes some odd assumptions. // Othello in the 21st century: The T S Eliot Prize.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The IMF’s latest AI and jobs report makes some odd assumptions

There’s a new report out from the International Monetary Fund that says that globally 40% of jobs will be affected by AI. That’s a big number, and frankly when you look across the trend in the literature on the impact of AI on work, it’s a bit of an outlier. Sure, back in 2013 Frey and Osborne produced a model that that said that 47% of US jobs “were susceptible” to AI.

But generally, these numbers have been coming down in other studies over the last decade. So I thought it was worth trying to understand the IMF analysis a bit better. Because, on the face of it, it’s at least possible that there’s something else going on here.

Their full report is here, and here’s the summary on their blog, bylined by the IMF’s Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva.

Here’s the rather bald global summary:

The findings are striking: almost 40 percent of global employment is exposed to AI. Historically, automation and information technology have tended to affect routine tasks, but one of the things that sets AI apart is its ability to impact high-skilled jobs. As a result, advanced economies face greater risks from AI—but also more opportunities to leverage its benefits—compared with emerging market and developing economies.

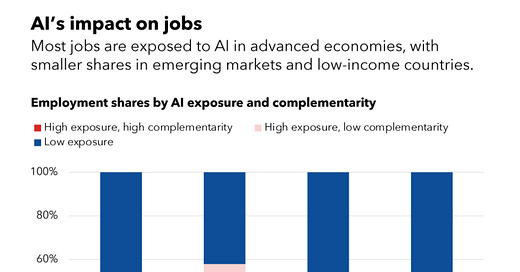

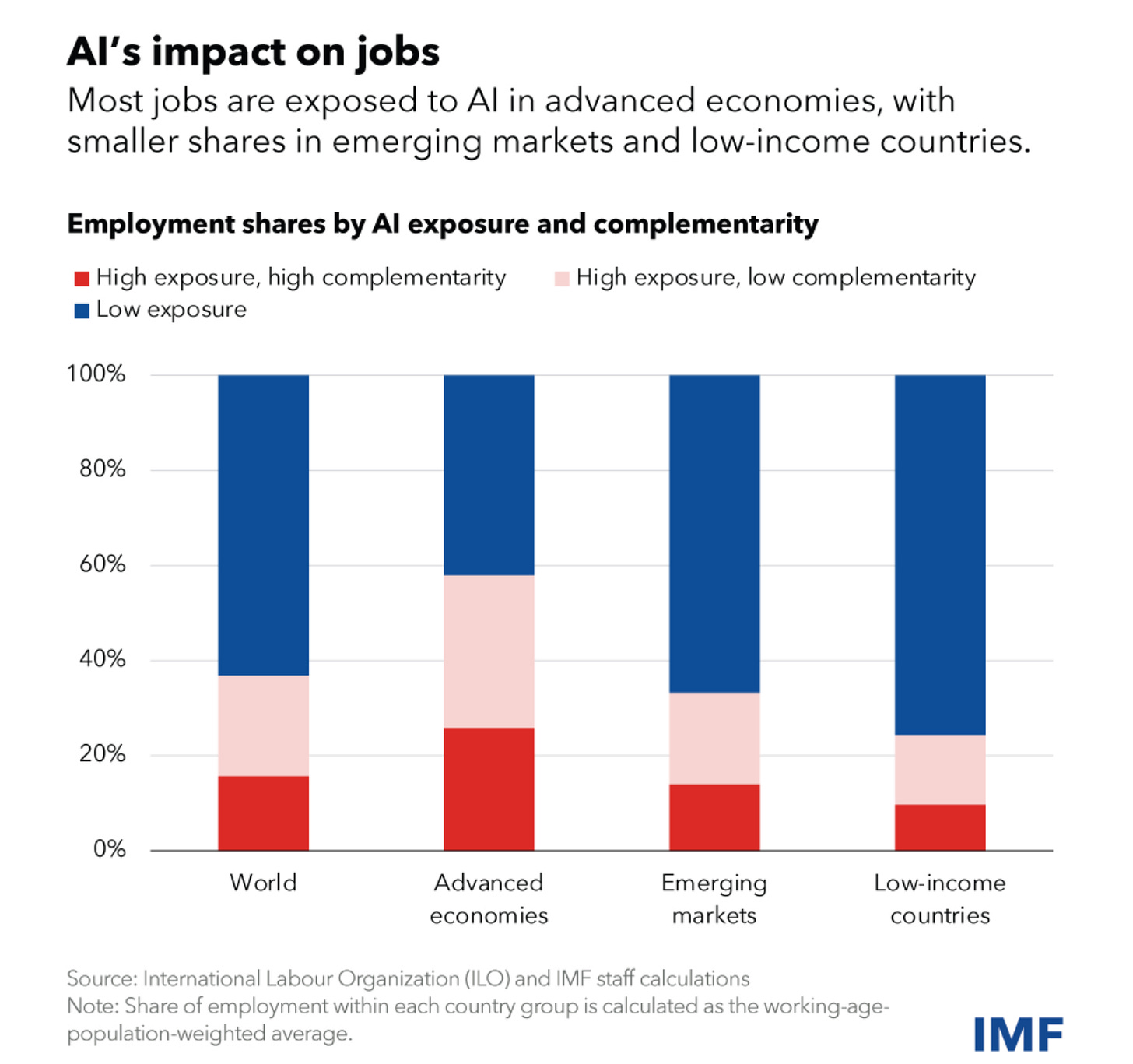

In advanced economies, they say, this figure rises to 60%; in emerging markets and low income countries, the figure is between 26% and 40%—less risk, but less exposure to benefits.

The paper is positioned as a Staff Discussion Note, which is a way of saying that it doesn’t represent the formal view of the IMF. The authors say they are trying to add to the existing literature in four ways:

instead of just looking at ‘exposure’ of particular jobs to AI, they are also trying to assess complementarity and substitution. This takes them into the context of particular jobs—social, ethical, physical;

they try to assess the potential for workers to transition to roles with higher AI complementarity

they seek to explore the impact of AI on wealth and income within countries;

they look at the comparative preparedness of countries at different income levels to prepare for this shift.

So on the face of it, this seems like an attempt to get to a reasonably rich analysis, with some scope for benefits as well as shocks, although that’s not how it got covered in the media.

And reading it as an interested lay person who tries to follow this literature, one of the modelling assumptions jumped out at me:

although in the model analysis activity grows in occupations with high AI complementarity and falls in low-complementarity occupations.

Because it’s not clear why that should be—the “low complementarity occupations” that they are talking about here are typically care or service jobs, and it’s not clear why activity should fall in these. Sure, you could use AI to help schedule a refuse truck route better, but it’s still going to involve people picking up rubbish from the street and dumping it into a truck.

I’ll come back to this below.

There are also some important caveats: workers will migrate to roles with different skills profiles, but the researchers don’t have a view on how long that will take (but I bet the model does). The pace of AI adoption is impossible to assess, or the rate at which firms will invest in it. But there does seem to be an large unstated assumption here that AI will have a big effect and it will work out exactly the way that firms that invest in it intend it to.

The idea of “complementarity” emerges from a model that says that jobs are bundles of tasks—and this is in line with the literature. It means that as technology or other circumstances change, the bundle of tasks tends to evolve in response. (They don’t use this example, but when I started work, there were still quite a lot of secretaries employed. Not so much now, but the parts of those jobs that involved organising things have turned into office coordinators, project managers, and executive assistants).

They add to this an idea of “shielding”: that society will place limits on some types of AI applications. They suggest, for example, that judges, who work with texts, are both exposed to AI but also shielded,

because society is currently unlikely to delegate judicial rulings to unsupervised AI.

This, of course, is a large misunderstanding of what judges actually do, and suggests that economists ought to get out more, or at least read some social anthropology.

But to continue their analogy: clerical workers are exposed to AI and less shielded, although of course conventional computing has already had a pretty serious effect on clerical workers over the past 40 years.

Anyway, this framework gives them a three box model:

“high exposure, high complementarity”;

“high exposure, low complementarity”; and

“low exposure”.

They see the first as being basically high-status cognitive knowledge work with high degrees of interaction: “surgeons, lawyers, and judges”. The second are less skilled: their example here is “telemarketers”. The third, they say, covers “a diverse range of professions, from dishwashers and performers to others.”

Apart from the slightly strange examples, it’s not at all clear what sort of tasks they consider to be exposed to AI, or what mix in the task bundle makes the different between “high” or “low” exposure. You can’t help but think that this really needs to be, say, a five point scale across these two dimensions rather than an on/off switch.

And there’s no sense that occupations might gain from AI. Anecdotally, for example, I was told by a head who was using AI to help his teachers do their admin that it had reduced fatigue and stress levels because it helped them to focus on the parts of the jobs that were about education.

The problem with not having enough granularity here means that it is hard to assess a lot of the other claims that are being made here. But let me note them anyway:

The share of employment at risk of displacement — high-exposure, low-complementarity— is broadly similar across income quantiles

This is different from previous waves of automation and information technology, where risks of displacement were highest for middle-income earners

But employment in high-exposure, high-complementarity jobs, where they expect the income gains to be made, is more concentrated in the upper-income quantiles.

I’ve focussed here on the assumptions about specific job types rather than countries. And this post is already too long. But there is a couple of things to add.

Once you have this model, the implication is that inequality increases—and hence the IMF press release headline. The study uses the recent history of the UK as a way of calibrating the relative impact of technology change on the labour share of income, on the basis that the UK is relatively exposed to AI use. The time period they choose is 1980-2014. From this,

we assume that the labor share declines by 5.5 percentage points following the introduction of AI.

But there are a few other quite important factors that led to much of this decline in the UK: deregulation and privatisation, a sustained political assault on the power of the trades unions, the opening up of global production in Asia.1 This may be getting things the wrong way around. Xx (David Autor came to a similar conclusion about the decline in labour share of income in the US over a similar period).

Given that the IMF was instrumental in advocating for much of this, across the world, perhaps the researchers are blind to it: there’s not enough detail in the report to work out if they have taken this into account or not.

So what’s the IMF’s interest here? Probably trying to maintain relevance in a world where its previous world view is largely discredited. Because otherwise the Managing Director wouldn’t have signed the blog post.

2: Othello in the 21st century

(Paolo Veronese. The Feast in the House of Levi. 1573. Public Domain via Wikimedia)

The annual T.S.Eliot Prize is always a good guide to the state of contemporary English language poetry. This year’s shortlist seems to be wresting with questions of place and identity, with Caribbean and Irish voices well-represented, although even putting like that over-simplifies, with many of the ten poets on the list living between places.

The chair of the judges, the Irish poet Paul Muldoon, summarised the short-list in this way:

‘All these poets properly reflect that disruption (of their present moment). Shot through as they are with images of grief, migration, and conflict, they are nonetheless imbued with energy and joy’.

The winner, Jason Allen-Paisant, is a Jamaican academic writer who teaches at Manchester University. His book, Self-Portrait as Othello, published by Carcarnet, completed a relatively unusual double by winning the Forward Prize as well at the end of 2023.

He wrote about the book for the Poetry Book Society:

"Given the dearth of archival representations of African lives in Renaissance Venice, I wanted to move physically towards Othello by visiting that city; I did so twice. In Venice, I observed the lives of African immigrants and stood for hours looking at paintings in the Gallerie dell’Accademia. What struck me in paintings by Veronese, Titian, and others, were their portrayals of African characters; these felt like a different history of representation of the Black body, a complex, if ambiguous one.

In a more academic voice, on the Carcanet blog, he also positioned the book in the context of modern Europe, in which — drawing on the scholar Anna Marie Smith — “the immigrant becomes the post-colonial symptom”.

Well, my mother would say that you should read poetry rather than talk about it: the poem’s the thing, as it were. So here is a poem from Self-Portrait as Othello, from the Forward Prize site, where it was published with the permission of Carcarnet. I hope that the business of transferring this to Substack hasn’t wrecked the layout. And if you prefer to have your poetry read to you, there’s a video of Jason Allen-Paisant reading the poem below.

The Picture and the Frame

1.

I have found no word for the effect of the light on the water

other than mare=ballerina, the one Gino Severini invented.

*

Nothing makes sense until it makes sense in the body, till the

the body is present at the making-sense.

*

There’s a set of people selling small things on the Piazza San

Marco. What should we call these small things, since what

they actually are doesn’t matter? They throw these things in

the air. I approach one, asking what they are. Lanza, he says.

A toy for kids. For demonstration, he throws one, catching

it back. 8 euros, he says. There’s this set of people. I’ve seen

them seeing with their feet, their backs, their entire bodies.

I’ve seen them knowing when to run from the police before

the police are in sight. Have you seen them too?

*

Eight years I’ve been trying to name this recognition

expressed in my flesh.

*

Mare=Ballerina is supposedly about a dancer, one who, in hermovement, evokes the crashing of the waves on the seashore.

For me, it evoked the light over the Canal and its houses,

the Venice I saw, wondering what The Moor saw, that Moor

who arrived here at such a point in the 16th century that he

could have been at home in Carpaccio’s Miracle of the Relicof the Cross at the Rialto Bridge. That he could have been thatgondolier, the sharp looking dude. That Venice, that canal,

that light seen from the oriental windows.

*

The Venice expressed in my flesh, as if the spirit of the sea of

back home was also here.

*

Where you from? The people selling the small things greet melike this when my eyes meet theirs. It’s the only way to greet,

as if to say, why, who, you, here – you who see me.

Ali, 21, from Senegal guesses at where I’m from in Africa.

He sells bracelets.

Buy a bracelet to support me, pour me soutenir. We bondthrough the French language. We move around in the wide

world, forced into fluidity. It’s not my style but, of course. He

gives me an additional one for free. Porte-bonheur. Pour lesenfants.

2.

In Veronese’s Feast at the Home of Levi, conceived in fact as a

depiction of The Last Supper before the artist’s brush with the

Inquisition, a young, dark-skinned man dressed in red tunic

and turban shares the frame with Jesus and the apostles.

All of a sudden, with Veronese’s hedonistic canvas, one enters

a time without really entering it. The painting becomes a joke

on the viewer. A door to a chamber is shown without any

key whatsoever to access it. One’s only consolation is to say,

I have seen that we were here, so normally here, in another time.Without any witness (writing, inscriptions, books, legends) tying

that time to the present, all the stories have to be invented—

reinvented.

*

In the window of Nardi, the jeweller’s, there are Blackamoor

brooches. There are rings made of diamonds and rubies with

miniature heads of turbaned Moors in sculpted ebony.

*

The intervening history of the representation of my body in text.

*

For Veronese, this painting was all about invention, and for it, he

took huge license with theological doctrine.

*

There are Moor heads everywhere. We’re not talking about this.

*

One wonders what kind of a character he is, this red-turbaned

African man present at the banquet of a Renaissance prince. He’s

talking to a fat white man dressed in fancier robes. The fat dude

looks into the distance distractedly. One can’t help but notice the

wily look on African dude’s face, but only after a while do you

notice his hand reaching into the other man’s bag. Disappointing

to say the least. The other African figures in the canvas occupy

subservient roles, like pages, but they’re also comfortably there.

They’re looking people in the eye, even having conversation.

Ambiguous. But with ambiguity, I find myself stepping into

a different history of representation. Ambiguity is a fucking

revolution. It’s almost overwhelming.

*

All I have is invention. All I could ever do is invent. I was

tired of invention.

*

There’s all the stuff that the European viewer can’t see, all the

stuff they haven’t allowed themselves to see.

*

The Moor remains invisible, despite the obsession with his

body.

There are readings from all of the short-listed poets on the T.S.Eliot Prize youtube channel.

j2t#535

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

In the text they say: ”The decrease in the labor share has historically been associated with routine-biased automation and, to a lesser extent, with increased trade, growing markups, and declining worker bargaining power resulting from the weakening of labor unions.”