3 October 2022. Politics | Planes

Making sense of the British government—or not // Getting aviation to net zero—or not

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

This is the second part of a two-part article on the UK’s political and economic crisis. Part 1 is here. Apologies that parts of Saturday’s article were repeated in the email; a little workflow problem. Thanks to those who mentioned it.

1: Making sense of the British government—or not

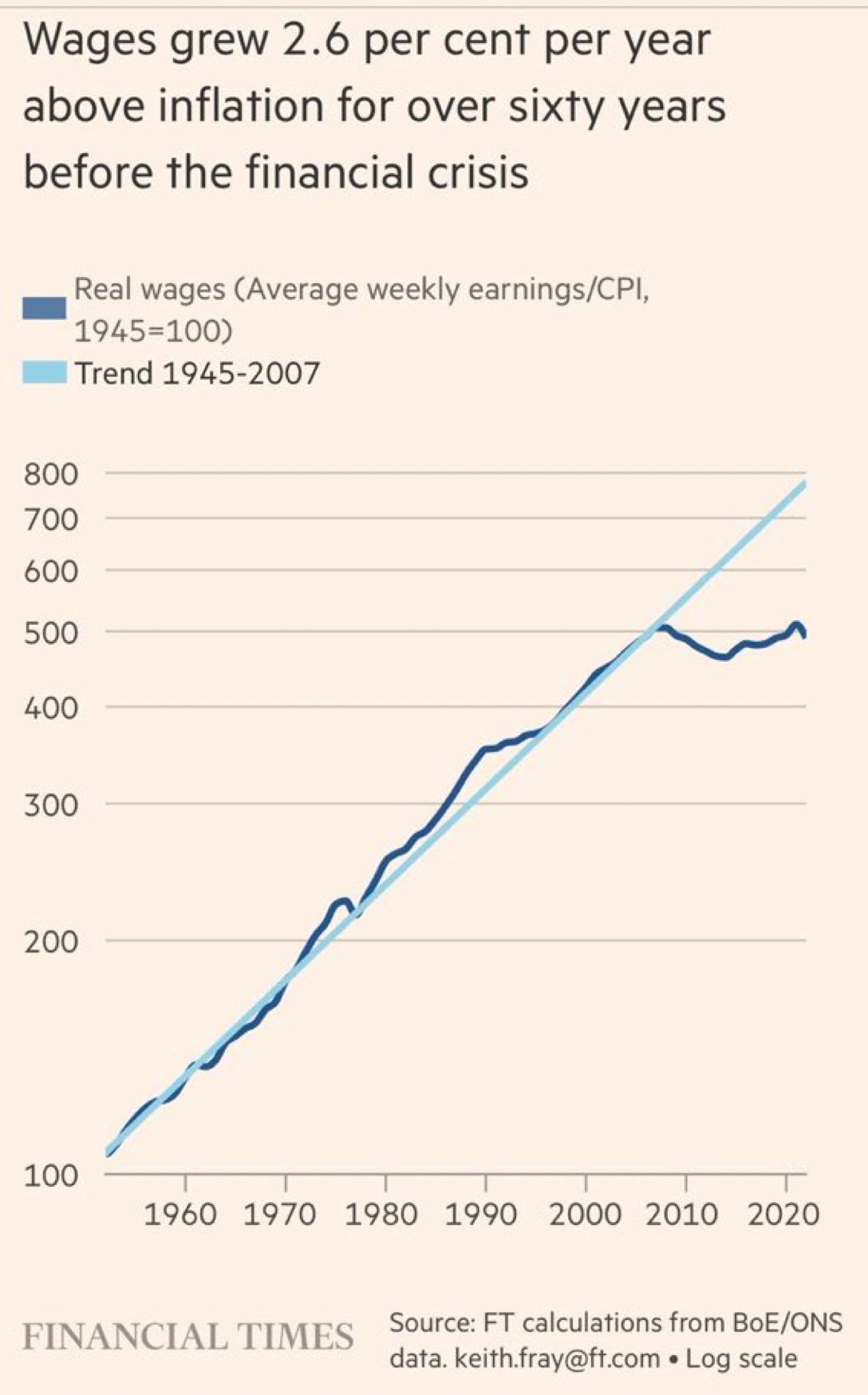

I wrote about the Conservative—and British—political and economic crisis on Saturday, and positioned it as the end of a 40-year wave. But for a moment, let’s take the so-called ‘mini-Budget’ at face value. If, as I said on Saturday, the rise in inflation and interest rates had wrecked the UK’s low-wage, low-interest rate economy, then the government had to do something.

So, if you want to be generous to the budget-that-wasn’t-a-budget, you can say that it was, as claimed, an attempt to do something about productivity. I’ll pretend for a moment that Truss and Kwarteng were being honest when they said it was a ‘budget’ about growth.

(Source: Financial Times—also shared in Saturday’s post)

But even this hits an immediate problem. In the 1980s, the idea of trickle-down economics and the Laffer Curve was contested, to say the least, but hadn’t been disproved. Similarly, ‘freeports’ and all of the other mechanisms of supply side economics had not yet been discredited. They represented then part of a suite of theories about how to solve the problems of the previous economic model. But everyone knows that’s no longer true. 40 years on, these are burnt out ideas that don’t work in the way their advocates thought they would.

Eric Beinhocker and Nick Hanauer spelt out some of the issues in an article in The Guardian:

As Truss put it last week: “Lower taxes lead to economic growth, there is no doubt in my mind about that.” There may be no doubt in the prime minister’s mind, but there’s a lot of doubt in the data. The US has had four decades experimenting with this kind of economics, and the evidence is clear: not only does it not work but it does enormous damage to the economy and society.

So what’s going on with our new administration? I think there are four alternatives.

1. They are zealots who don’t realise that the ideas they have believed in for decades are no longer fit for purpose.

2. Or they are working a clever plan to create a crisis to force further cuts in the size of the state and of public spending.

3. Or they realise that they are only going to get one shot at this, and they have decided to help their friends and political supporters cash in before the house comes crashing down around their ears. (Corruption, in other words).

4. Or they aren’t very good at politics.

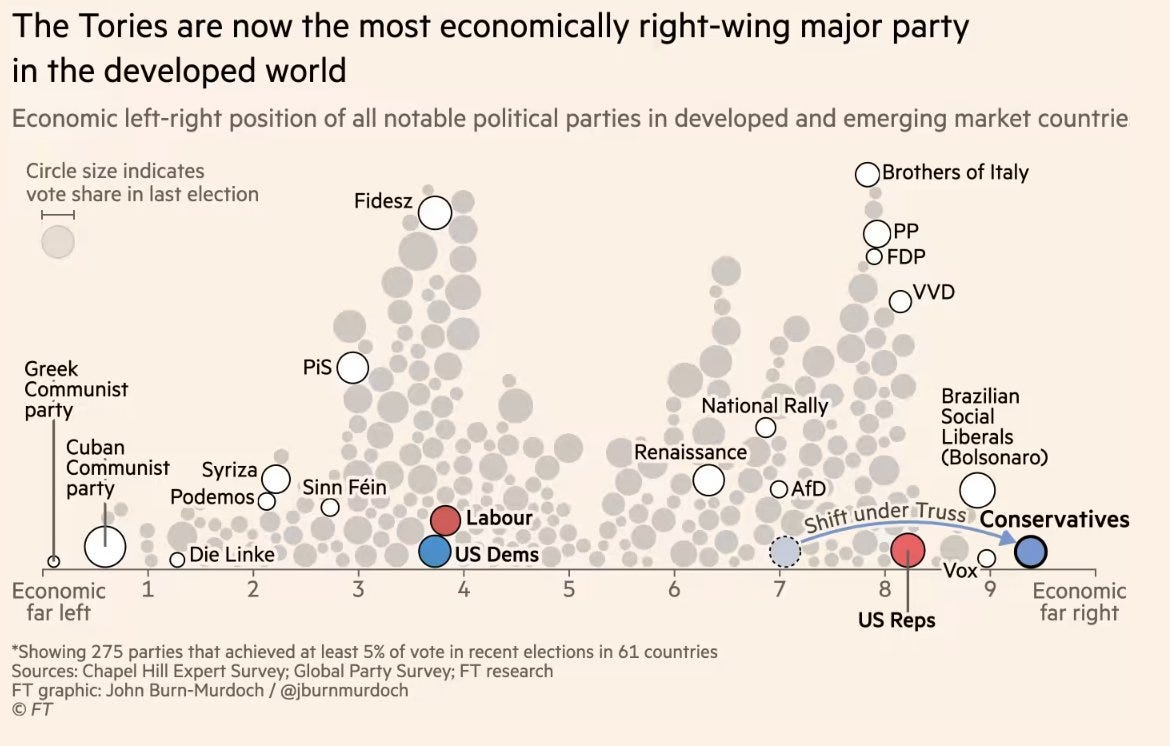

Measuring ‘zealotry’ is hard, even though you know it when you see it, and usually people just point to the libertarian economic manifesto, Britannia Unchained, that Truss, Kwarteng and others co-authored a decade ago. But while I was writing this piece, the Financial Times’ data journalist John Burn-Murdoch published a handy chart mapping economic policies by political party across a number of countries.1 The policies of the current Conservative administration are now right at the edge of the scale, having shifted from the centre-right mainstream to the right under Truss (‘jumped’ or ‘lurched are more accurate descriptions).

(Source: Financial Times)

Of course, some of the evidence fits several of these interpretations. Firing the head of the British Treasury department and then declaring that your Budget is a ‘mini-budget’, to avoid scrutiny, could be zealotry, or it could be cashing in, or it could be incompetence.

It’s probably doesn’t go with the ‘clever plan’ version, though, since the Treasury went along with years of Osborne’s austerity without kicking up a fuss despite the economic damage it was causing. (There are other views on the ‘clever plan’.)

My own view, briefly, is that it’s a heady cocktail of zealotry, corruption, and incompetence—that all three have interacted with each other to create the current crisis. You could even say that the current crisis is over-determined, because any two of these would have been enough.

It is impossible to avoid the smell coming from the British government at the moment: the Chief of Staff who is of interest to the FBI, the Conservative billionaire hedge fund owner and Conservative donor Crispin Odey who used to employ the Chancellor who has made millions shorting the pound as a result of its collapse following the budget—with just a sniff of private information beforehand. Odey seems to have salvaged the fortunes of his hedge fund by doing this. Not to mention the Cabinet Minister and former (briefly) Chancellor of the Exchequer whose possible tax avoidance scheme continues to raise questions.

This list could go on, but it’s been a theme of the 2019 ‘Brexit’ government. The same corruption was seen throughout the pandemic procurement scandals.

As for competence, one of the signs of decline of a party is a shrinking pool of talent. The political talent pool has been shrunk more generally by the professionalisation of politics, but the Conservatives have accelerated this through expelling some MPs and by pushing through its pursuit of their ideological version of Brexit.

In The Critic, Mike Jones brought these two ideas together when he noted the shallowness of much of the Conservative leadership campaign:

For (leadership candidate Kemi) Badenoch, modern-day Conservatism is pretty much hollowed out, at least in terms of policy...“What’s missing”, she wrote, “is an intellectual grasp of what is required to run the country.” While Labour is cementing its image as the party of productivity and investment, the Tories, though unintentionally, spend much of its efforts in making the party as unattractive as possible.

But the deeper problem is that the party’s underlying ideas—legacies of that 40-year wave I discussed on Saturday—are about a smaller state with less public capacity. Hence Jacob Rees-Mogg’s persistent desire to shrink the civil service. A decade of austerity has stretched the capability of the state, of public services, and of local authorities to close to collapse.

And one of the things we have learned, from the pandemic, from the climate crisis, and from the energy crisis, is that states need capacity if they are going to offer any kind of security to their citizens. Markets alone can not deliver this, even if they are well regulated. And they can no longer deliver growth either: we know, from the work of Mariana Mazzucato and others, that this requires all kinds of investment in public capacity.

Beinhocker and Hanauer described this as “middling out” economics, and it requires public investment:

a robust economy of thriving middle-income families is not a consequence of economic growth, it is its cause. So the policy priority is then to invest in the broad population of working people: education, healthcare, childcare, elderly care, worker training, affordable housing and good public infrastructure, from transport to broadband. It is also critical to support people with a living minimum wage and enough economic security that they aren’t economically trapped and can take risks, from starting a new business, to taking time out to reskill.

Johnson’s maverick style allowed him to nod in the direction of all of this, at least rhetorically, even if he had little intention of doing it. The political effect of Kwasi Kwarteng’s budget for the rich, along with Truss’ belated conversion to energy support, and the rolling crises that followed it, was to make voters realise viscerally—almost in a single day—how much they need the state to be on their side, to look after their security, in the 2020s.

2: Getting aviation to net zero—or not

Jet Zero is the name of the British government’s scheme to get aviation emissions down to, well, net zero, by 2050. You can see what they just did there. But my sometimes colleague Glenn Lyons has a post on LinkedIn where he suggests that the ‘net’ bit of net zero is doing a lot of lifting in the plan.

Even though Jet Zero is described as a ‘high ambition’ scenario, it would leave

19.3 MtCO2e/year still being emitted (domestic + international) in 2050. Pre-COVID annual emissions were 38.2 MtCO2e/year.

In other words, it’s still emitting in 2050 half as much CO2, and this is being covered by offsets. And as we know, offsets are an unreliable way of doing this (the emissions are now, the offsets are later—assuming that they’re not in forests in Spain or the American West which then go up in smoke. Yes, this happened.)

In theory, this is a slightly more impressive plan than it looks at first sight, since the government believes that the growth of the aviation sector that was projected out to 2050 before the pandemic is still going to happen—a 70% increase in passenger numbers by 2050, in other words. That might get harder to sell politically as climate change gets worse and the it becomes more widely known that the top 1% worldwide are responsible for 25% of emissions.

And to put the slightly incredulous icing on this particular cake, the Jet Zero report also says:

The strategy notes that "(m)any of the technologies we need to achieve (Jet Zero) are at an early stage of development or commercialisation; their nascent nature means that we do not yet know the optimal technological mix out to 2050". Read also as: we do not yet know how far technology can take us in decarbonising aviation.

Maybe unsurprisingly, Glenn isn’t too impressed by this. His take is:

✈️ Aviation as an industry not only wants to survive but to thrive through growth.

✈️ Having been a form of consumption for the few globally, growth is sometimes portrayed almost as a public service—giving more people more opportunity to benefit from flying.

✈️ On the basis of growth, an optimistic outlook is entertained that technology and offsetting will allow 'sustainable aviation growth' in a Code Red world.

✈️ Jet Zero has 5-yearly monitoring intentions but invites us to grow aviation first on the promise that decarbonisation will, or may, come later.

He also points us to an article by Carbon Briefing that has more analysis of Jet Zero.

As it happens, Glenn and I worked (with Charlene Rohr) on a report for the DfT on mapping routes to Net Zero for different modes. I wrote the aviation chapter in that. If you actually want to get zero emissions, at least at point of use, by 2050, the stumbling block is long distance flight.

I summarised the chapter in a few lines in the comments below the article:

It depends how far you want to fly, how many people want to fly, how quickly key technologies evolve, and how strong the incentives are for airlines to introduce new technologies.

In short: if battery technology keeps improving, this should be good for short-haul. If hydrogen planes work, they should be good for medium haul (but unlikely to come into fleets at scale until after 2050). For long haul, on current designs of planes, you really need Direct Air Capture to work at scale, and hope you get a bit of the biofuels that are produced, and even then you’ll be talking about a fraction of the current long-haul flights.

As it happens, the replies to Glenn’s post are quite a rich discussion. One observation I hadn’t seen before in the aviation discussion, from Niall O’Hea, is that the ‘Jet’ bit of the Jet Zero is part of the problem:

Worth digging out the book Fly and be Damned by Peter McManners—one item he offered was that propellor aircraft are much more fuel efficient and whilst slower, require less maintenance. Our world has a speed addiction … maybe a 180 turn into how we can travel most efficiently could be transformational?

Glenn did a set of futures dialogue workshops on the future of car use a little while back. As he suggests in the article, doing the same thing for aviation might be a good idea.

j2t#375

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The article is behind the FT paywall, but the methodology comes from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey.