1 October 2022. Economics | Cars

The Conservative crisis and the 40-year wave // The costs of cars

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

I missed yesterday’s post because I started writing a piece about the British economic and political crisis that got longer and longer. Part 1 is here, and Part 2 will follow on Monday. Have a good weekend.

1: The Conservative crisis and the 40-year wave

To borrow Hemingway’s famous phrase, political and economic crises happen slowly, then all at once. And when they do happen all at once, there are lots of immediate reasons why. The current economic and political crisis in the UK is largely self-inflicted, which raises the question of ‘why?’, but can also be thought of as representing the endgame of a long political wave.

No, you can’t know when the actual moment will be. But over a long period of time, the options keep narrowing until there are no good choices left, at least for the party and politicians that have benefited from that wave. Every political party hits a zugzwang moment.

I think it was the politics academic David Runciman who observed that if you looked back over a century of British politics, you could see cycles that ran from economic crisis to economic crisis every forty years or so, with a political settlement coming around a decade later. I can’t find the source for that, though.

This is a heuristic, not a law, and the timings are approximate. But, indicatively, the long depression of the late 19th century ran to 1896 (with Baring’s Bank bailed out in 1890); the 1929 crash led to the depression of the 1930s; the oil crisis happened in 1973-74; and, then of course, there was the 2008 crash.

The political effects of these: the ‘Liberal landslide’ of 1906, the Labour win in 1945 (complicated by the experience of war), Thatcher’s win in 1979 and subsequent victories in 1983 and 1987. And the 2008 crisis is still playing out in our politics today.

It happens that you see this two-generation pattern in other bits of the literature. Strauss and Howe’s idea of the ‘Fourth Turning’ basically proposes a four-generation model from crisis to crisis. Their four generation pattern more or less goes ‘build’/‘enjoy’/‘exploit’/‘unravel’, although that’s not the language they use. It follows a classic long-run systems pattern, even if some of their post-hoc timings are spuriously exact.

All the same, the mechanism is visible. A crisis leads to a system reset, designed to solve the problems that caused the crisis. For a generation you get a reinforcing loop as the system benefits from this new set of ideas. But all systems decay over time, and a balancing loop kicks in as the problems caused by those new ideas come to the fore.

The advocates of the previous set of reforms retire or die off, and a set of ideas that had some coherence to them either become incoherent, or simply no longer fit the changing political and economic landscape. As David Muir noted, Thatcher said this explicitly of the Labour Party back then:

He added:

Now applies to the Conservative Party.

So the current British political and economic crisis can be seen as the last twitch of Thatcherism, and by two of its last remaining zealots. I’ll be coming back to the-budget-that-wasn’t-a-budget later in this piece, but there’s another important element here. This is about the long-term decline and de-composition of the Conservative party.

I know this is a strong thing to say. We’re talking about a party that has a majority of 80 seats in the British House of Commons, and one of the givens of modern British politics is that you should never bet against the Conservative party. Over the last century it has been the most successful ruling party in Europe.

But it has been unravelling since the 1980s. In the 1950s, and the era of ‘One Nation’ Conservatism, the Conservative Party was also a social institution, with 2.5 million members across Britain. (In Barnet, in north London, which had 70,000 voters, there were 12,000 Conservative party members. By the 2000s, its membership was less than a tenth of this, and ageing fast. Social values had moved away from the party as well. Economics, which have punished the younger generation, means that the party’s vote is now heavily skewed towards the over-60s and the party’s policies have followed.

David Cameron’s attempted solution to this was to triangulate: a pretence at ‘one nation’ social values to voters (gay marriage and ‘hug a hoodie’,) with the party funds coming from an increasingly narrow base within the finance sector, and the core vote shored up with a message that drifted between patriotism and racism.

The first part of that was sheered off by UKIP and the Brexit, while the finance base got narrower (Johnson’s “fuck business” moment in Brussels was emblematic) but Johnson propped it up for a moment with the idea of ‘levelling up’, which appealed to enough voters beyond the traditional Conservative base to win an election. If you’re interested in the political sociology of all of this, the most persistent analyst is the sociologist Phil Burton-Cartledge at his ‘All That Is Solid’ blog—for example in these 2018 pieces—and in his book on the post-war history of the Conservative Party.

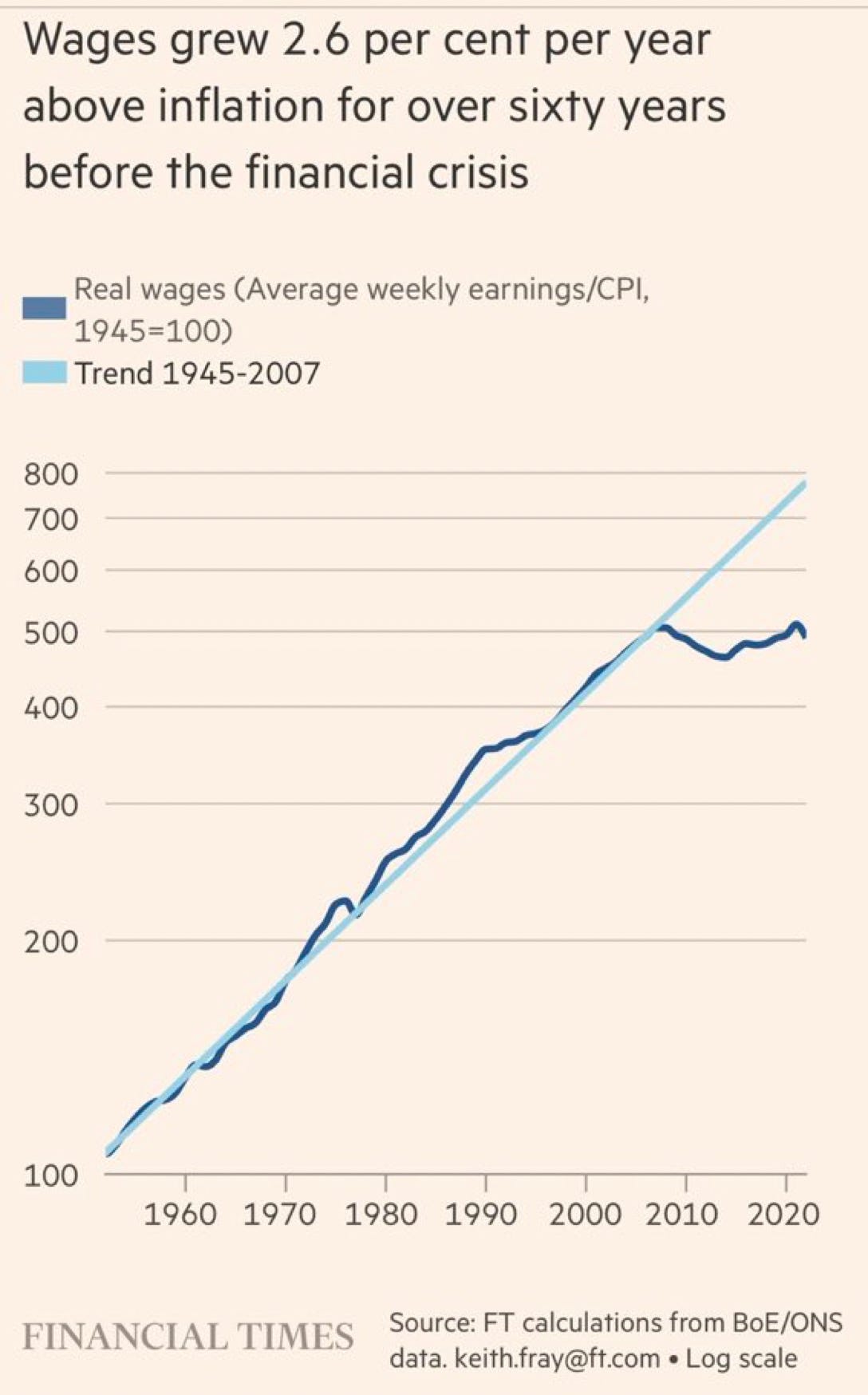

Levelling up was an interesting idea, if the Conservatives could have persuaded people that it was a strategy and not a slogan. At the least it could have been a programme that dealt with Britain’s real problem, which is captured sharply in a chart from the Financial Times a few weeks ago.

(Britain’s wage and productivity problem. Source: Financial Times)

The problem is this: wage growth, and associated productivity, in the UK have been flat since the financial crisis. The causes of this are either complicated, which is the version you get from economists, or they are post-crisis austerity, which killed off the initial post-crisis recovery, followed by Brexit, which had a calamitous effect first on business investment and then on trade.

These together have created the low wage, low investment economy that has characterised Britain recently, with a toxic combination of flat wages and low investment. Paul Mason explained how this worked in practice in a Guardian article a few years ago by using hand-washed car businesses as an example.

And one of the sharper observations on Twitter when inflation started picking up (you can never find a Tweet when you need one) was by James Meadway, who suggested that this low wage, low investment economy also needed low inflation and low interest rates to survive.

(Part 2 follows on Monday)

2: The costs of cars

I’ve been collecting images about the effects of cars, and I thought I’d share them today. These have come from Twitter and a few other places in my feeds over the past few weeks.

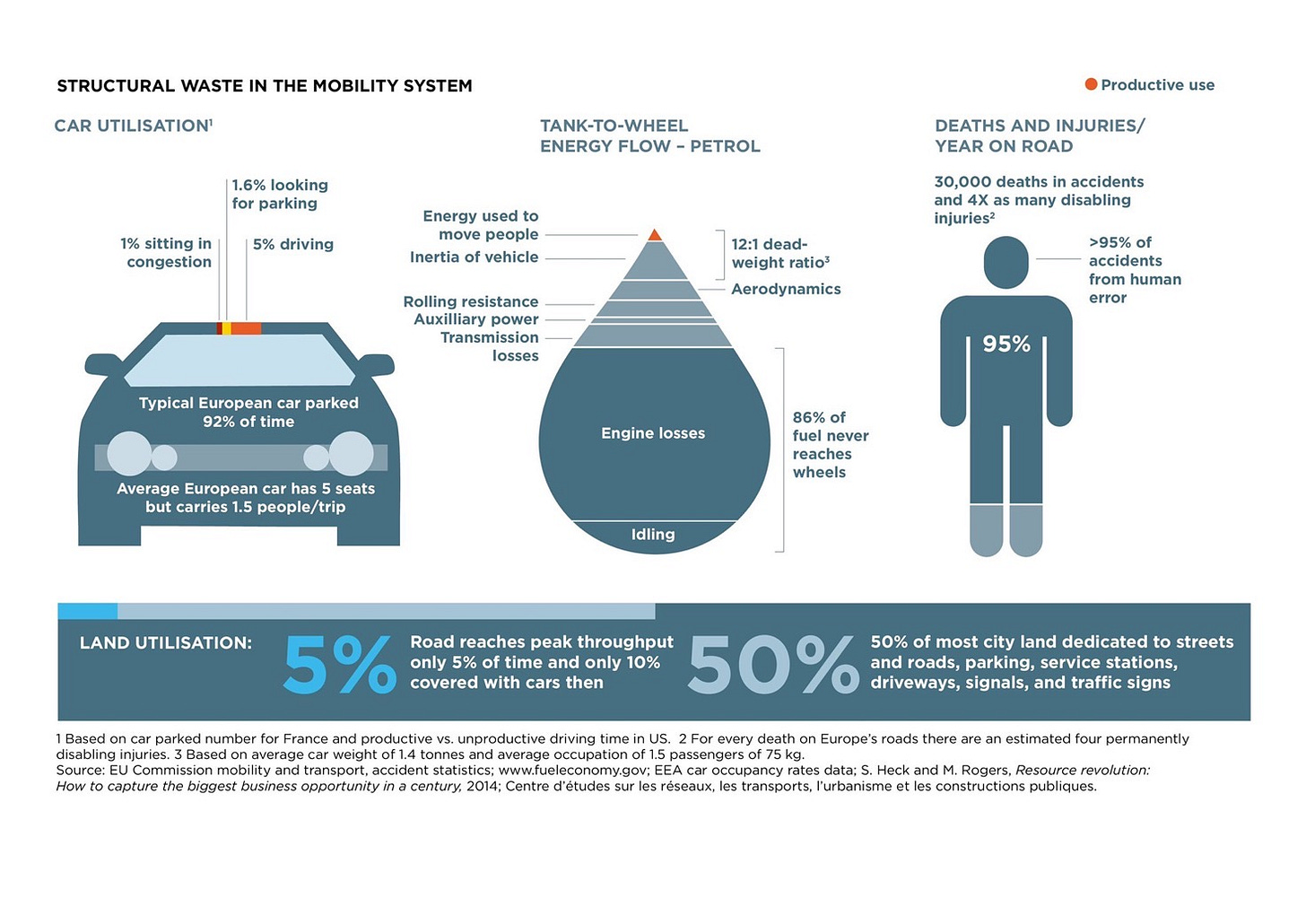

(From the Ellen MacArthur Foundation)

The first, which is a few years old now, looks at—effectively—the waste and damage caused by vehicles. The tiny red splash on here, representing ‘productive use’ is tiny. They hardly get used, so they are sitting around a lot. The internal combustion engine is astonishingly inefficient at converting energy into propulsion, and even when it does it is mostly moving the weight of the vehicle, not the passengers. And it also kills and injures people as it goes.

So the efficiency of the vehicle is affected a lot by the weight.

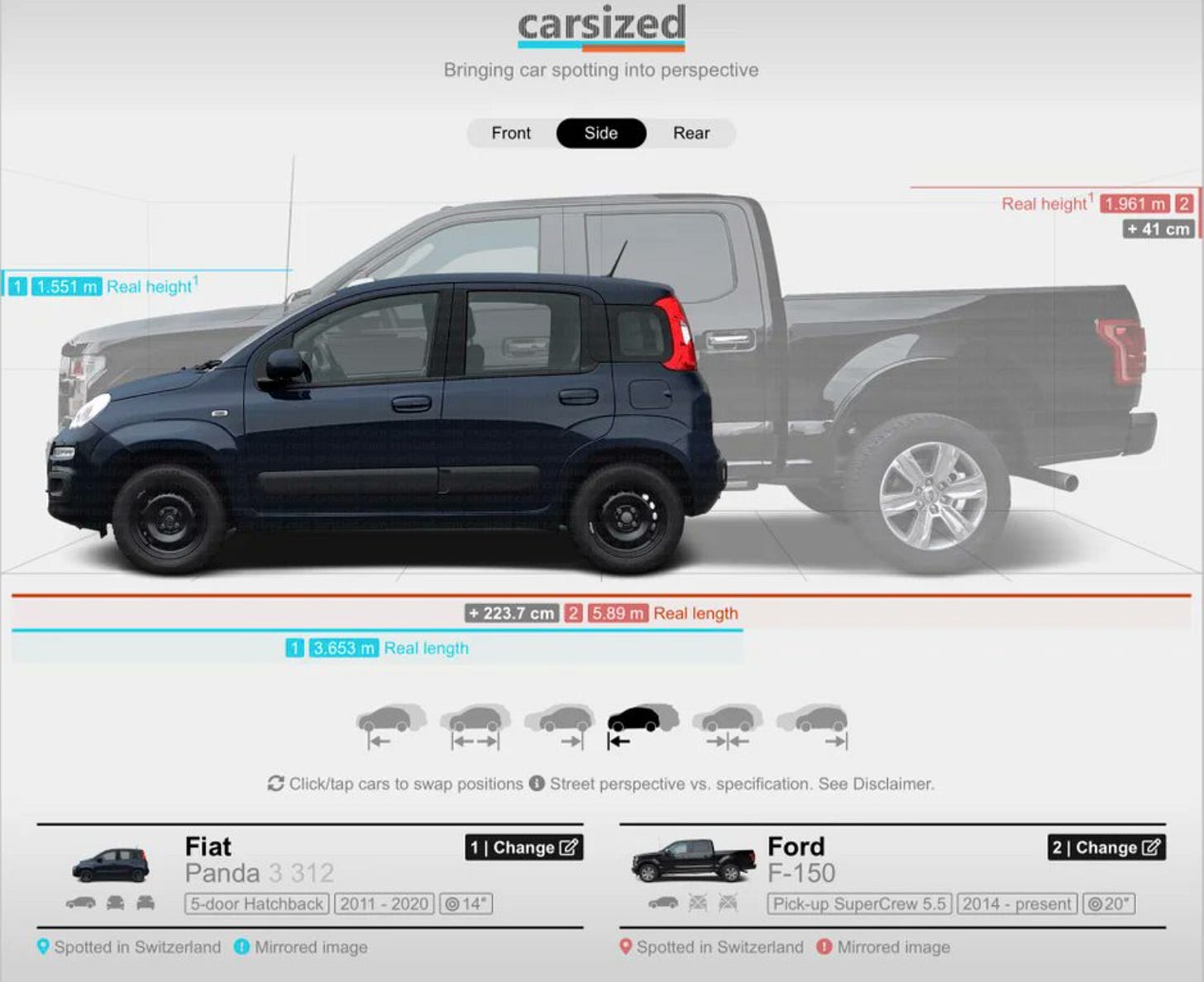

(Most popular vehicles in Italy and the USA. Carsized, via Adam Tooze’ newsletter)

Which means that this image, showing a typical Italian car compared to a typical American one, is striking. There are other consequences of weight. The impact on the road of a vehicle is proportional to the cube of its weight, so heavier vehicles also generate a much bigger (and climate unfriendly) amount of road maintenance.

Which is also one of the reasons that motorists’ endless calls for cyclists to pay “road tax” are so ridiculous—a typical bike is around 13kg, a typical British car about a tonne, so a car has about a third of a million times as much impact on the road surface as a bike does.

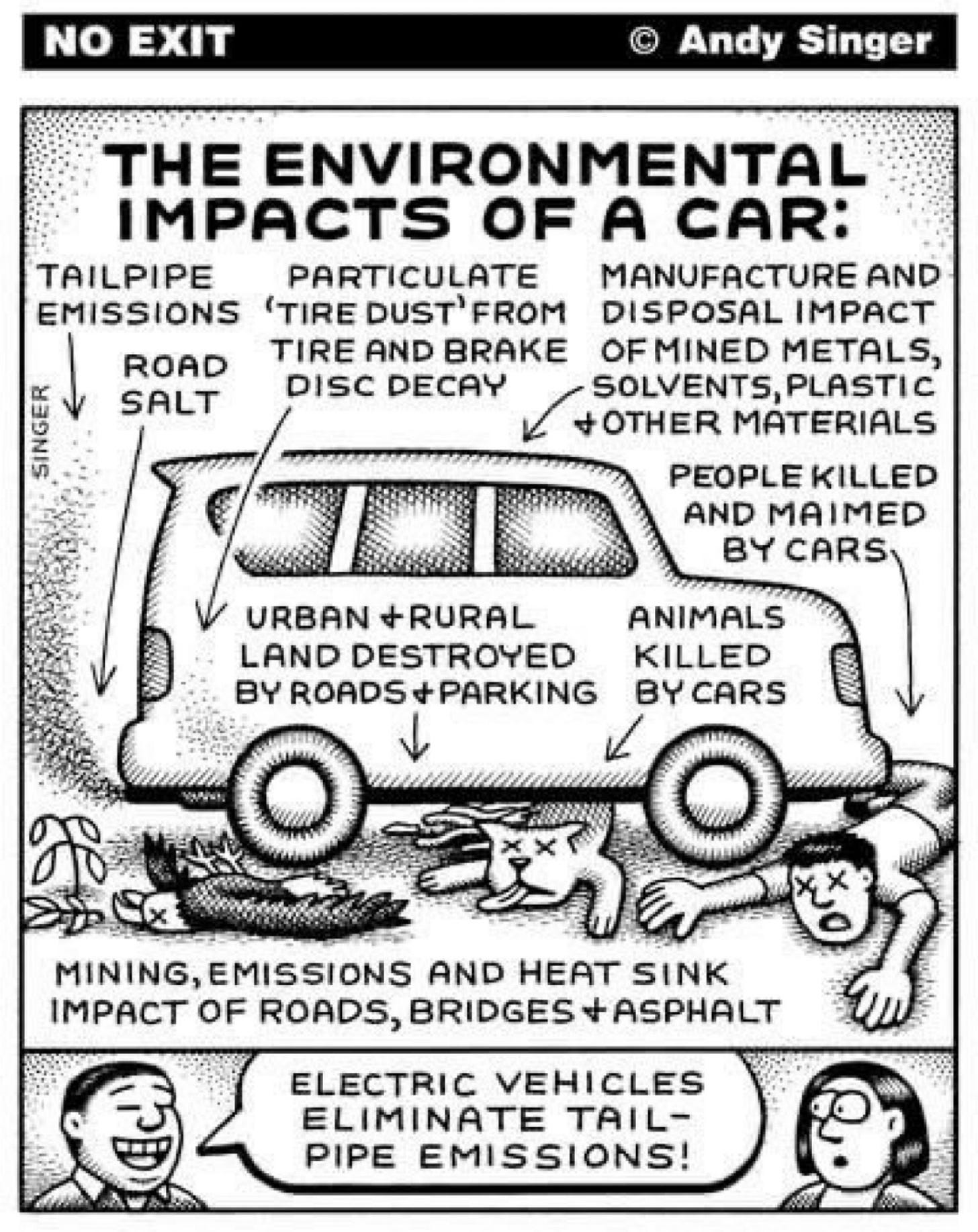

(Cartoon by Andy Singer)

The great hope of the car industry is that electric cars will take the pressure of by removing the polluting effects of emissions, carbon included. But as this cartoon reminds us, this is only a tiny part of the story. Electric vehicles solve hardly any of the problems of car culture.

j2t#373

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.