29 September 2024. Social media | Collapse

The evidence on social media use and young people is still not clear cut. // States have a shelf-life of about 200 years. [#604]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish two or three times a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. Have a good weekend.

1: The evidence on social media use and young people is still not clear cut

It is September, and in Britain the return to school a couple of weeks ago was marked by news stories about schools banning mobile phone use in school time and parents signing a declaration urging other schools to follow suit.

So it seemed like a good moment to go back to a New Scientist article earlier in the year (in June, no longer online) that took the useful step of reviewing the evidence on the effects of phones on young people. The cover tag for the article was 'Growing up online'. The writer was Michael Marshall:

There are a lot of scary claims about excess screen time for children and teenagers: that it is harming their mental health, leading to depression, eating disorders and even suicide, and is cutting into time they would otherwise spend socialising or exercising, causing loneliness and poor physical fitness.

Tech companies, in short, are complicit in ruining our kids’ lives.

(Source: New Scientist, 22 June 2024. Image: Jason Ford)

The evidence, however, doesn’t support the bleak story that is told above. This doesn’t mean, all the same, that the current loose regulatory regime is a good thing.

What it does mean is that

we need to think more carefully about what healthy screen time for young people looks like and how best to make the online world accessible to them.

A 2023 review of usage data which compiled evidence from 2016 to 2021 found that 6 to 14 year olds spent an average of 2.8 hours a day onscreen. And although organisations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend that kids under the age of five should have little or no screen time, this doesn’t’t happen in practice. 2022 research found that only a quarter of chilidren under two had no screen time.

One of the ways in which the tech companies say they limit access to their platforms is by imposing age restrictions. But using a false age to sign up is common:

23% of UK children aged eight to 12 give their age as 18+ on social media apps.

That’s the problem statement, if you like.

What are the costs and consequences of this for young people? That is more contested. The article starts by making what it describes as “the case for the prosecution”:

that children's mental and physical health, and their overall development into well-rounded adults, is being harmed.

The lead voices in making this case are Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt. Twenge wrote iGen, Haidt The Anxious Generation. I’ve always found Twenge’s work problematic—she seems to conflate correlation with causation too often for my intellectual comfort—although I have more time for Haidt:

They point to evidence that the mental health of children and adolescents has worsened significantly in the past two decades. In many countries, growing numbers of young people, especially teenage girls, are seeking medical help for conditions like anxiety and depression.

There is certainly evidence that young people are having some bad experiences on their phones. 79% of young people have encountered violent pornography before the age of 18 (this data is from a UK parliamentary report) and 81% of girls and young women—between the age seven and 21—have “experienced some form of threatening or upsetting behaviour online”:

A 2023 study found that a third of children in the US have experienced cyberbullying, with a Canadian study from the same year finding that girls and young people from ethnic minority groups were more likely to be victimised.

There is unpublished US research that finds that cyberbullying is a “significant contributor to teenagers being admitted to hospital for psychiatric care.”

Social media has some particular harms. One study randomly assigned some participants to get fewer likes:

Those teens said they felt more rejected and had negative thoughts about themselves. Those who were being bullied or excluded by their peers were most vulnerable.

Jason Nagata, at the University of California, has done particular studies of screen time, finding an association between screen time for 11 to 18 year olds and a greater likelihood of later obesity and diabetes; and more videogame time for nine and ten year olds associated with a greater incidence of obsessive compulsive disorder two years later and an increased likelihood of suicidal behaviours.

When you look at all of this, it’s not surprising that parents and policy makers are calling for tighter controls on phone use and screen time.

But, and of course there is a but. When you look at the evidence of harms, it isn’t so strong. A lot of this research reports on correlation not causation. Measures of screentime are often unreliable, because they are often self-reported. Worse than that, as Pete Etchells of Bath Spa University tells Marshall,

”Screentime is a meaningless concept... it could mean literally anything.”

In general, when researchers conduct meta-studies that place more emphasis on the better conducted studies, says Marshall, “the evidence for harms has both shrunk and become more nuanced. “

One such meta-study looked at the wellc-being of adolescents, including over 353,000 young people between 12 and 18 in the UK and the US. They found that digital technology use explained 0.4% of the variation in well-being—not enough to justify regulation.

But when Twenge and Haidt and others analysed this same set of data, separating out social media use and gender, they found that

heavy use of social media is consistently associated with negative mental health outcomes, at non-trivial levels, especially for girls.

Similarly, one study found that screen use during childhood was associated with reduced literacy, unless parents watched with their children, in which case it was associated with improved literacy.

On my reading of the article, the more detailed analyses seem to suggest that the thing that causes the harm is the interaction between social media use and the person’s psychological state at the time. Amy Orben, at Cambridge University, says,

"A specific type of content for a really vulnerable individual at a very specific point in time when they're going through crisis can have harmful consequences."

Conversely, for those aren’t especially visible, the risks are low.

Researchers like Etchells and Orben suggest instead that we need to understand which online behaviours are beneficial or harmful, but this work is at an early stage. For example, active posting may produce benefits, while passive consumption might cause psychological harm. (The one study, in Norway, that has tried to test this found no relationship.)

And while the argument that photo-sharing apps might cause or worsen body image problems seems plausible, the research so far is limited. In 2021, though, the same Norwegian researchers found that girls who spent a lot of time interacting with social media posts developed lower self-esteem about their appearance. The same was not true for boys.

There’s also evidence of benefits from smartphone and social media use. One study found that 10 to 18 year olds who increased their time on social media spent more time with their friends offline. The two reinforced each other.

Amy Orben suggests that instead we need to work out how to design online spaces for young people; they have a right be online:

"Young people deserve to be part of the digital landscape," she says. "They deserve to build the skills and be able to experience the online world, because it's a key part of what our world now is."

This doesn’t let the tech companies off the hook. They still need to design in better safeguards and design out harmful features like ‘doomscrolling’.

There’s some research evidence that says that parents that engage with their kids’ online experience in this way, setting some boundaries while respecting their autonomy, were more likely to be trusted by their children than those who were more controlling about it. And that this also helped children develop a healthy relationship with social media.

2: States have a shelf-life of about 200 years

I gave a talk on collapse this week to the community of futurists that is co-ordinated by DEFRA, the British government’s Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. It was based on an article I wrote earlier this year, and discussed here in March. The presentation slides are linked at the end of this post.

While I was talking, the chat filled up with lots of valuable resources: a video explaining Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies; a discussion of Chesterton’s Fence; notes about the energy trajectory of our current societies, including the work of Rachel Donald, which I’ll definitely come back to here.

But the thing that immediately caught my attention, given my interest in long waves and futures, was an article by Luke Kemp and colleagues at the BBC Future website that discussed the timespans of states, and their patterns of decline. 200 years is about the average, which tallies with the 100-300 year window used by Peter Turchin and his colleagues working on ‘secular dynamics.’

Perhaps this isn’t surprising since Turchin draws on the Seshat model, which Kemp and his colleagues use as one of their sources.

Thinking about civilisations as being time-limited immediately leads you to a particular perspective about them, which is in effect, that as civilisations age they are more likely to show signs of decline, in the same way that we can make the same kinds of assumptions about people.

And from that, of course, we can start to build a view of what those signs of decline might be. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. Let me go back and discuss their approach to research and analysis first.

Luke Kemp is a research associate with the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study, and a research affiliate with Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.

The research here is into pre-modern societies, since if you are measuring how long they have lasted for you need to know that they have come to an end. They restricted their analysis to"states", which they defined as organisations that enforced rules over a given territory and population.

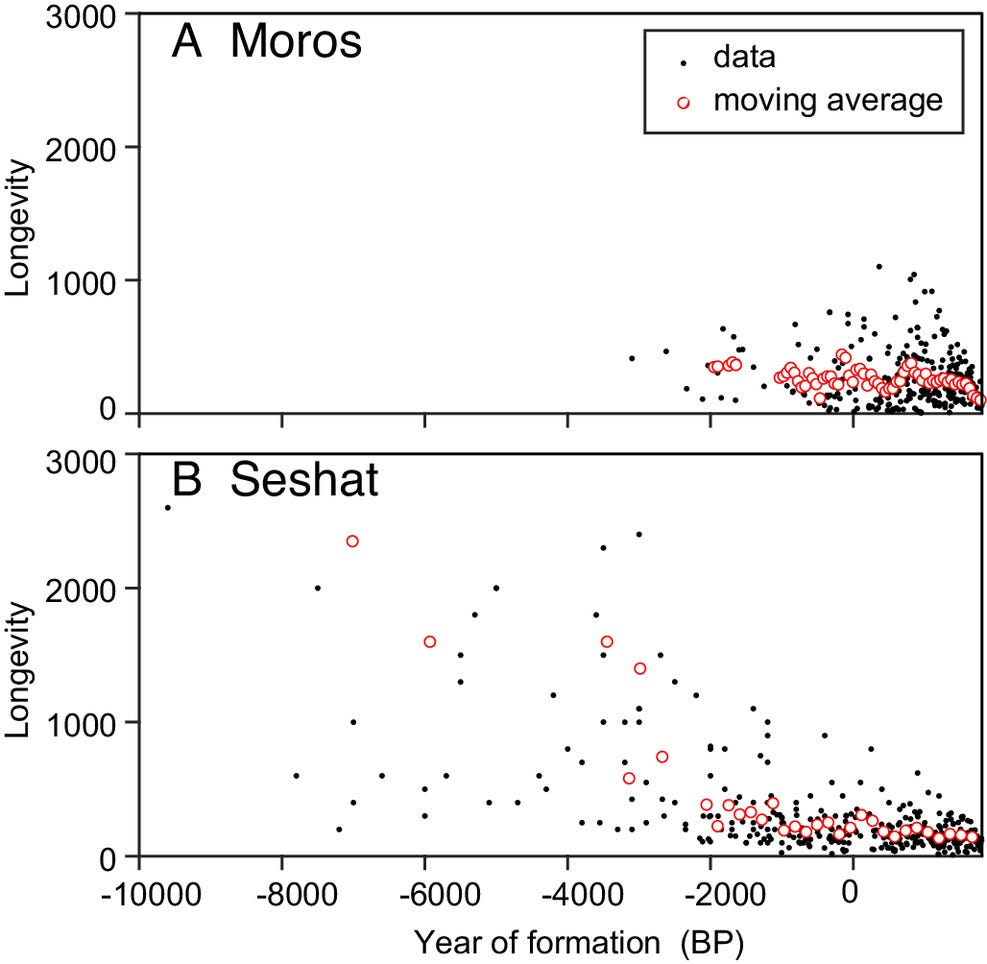

To collect data, they created their own database, called MOROS, which “contains 324 states over 3,000 years (from 2000BC to AD1800).” The data was assembled from other databases, an encyclopedia on empires, and so on. MOROS, by the way, is the Greek God of Doom. Academics are such wags.

As mentioned above, they also consulted Seshat, which has been curated over time by archaeologists and contains data on 291 polities. (Seshat? The ancient Egyptian goddess of wisdom, writing, and knowledge.)

(‘The longevity of societies plotted against their year of formation for (A) the MOROS database and (B) Seshat database. Red circles are means for time windows each covering 1% of the data’.1 Source: Scheffer et al.)

The two datasets, in other words, produce similar results. To do their research, they used a technique called “survival analysis”, which analyses the spread of lifespans:

If there is no ageing effect, then we can expect an "ageless" distribution in which the likelihood of a state terminating is the same at year one and 100. One previous study of 42 empires found exactly this. In our larger dataset, however, we found a different pattern. Across both databases, the risk of termination rose over the first two centuries and then plateaued at a high level thereafter.

This, apparently, is a similar finding to another recent study that found—in an analysis of historic crisis events—that the average polity had a life of 201 years.

In the academic article they summarise their findings like this:

In conclusion, the distribution of longevities reveals that the risk of termination rises over the first two centuries, and then remains roughly constant. That is, newly established states appear to have some benefit of youth in terms of survival chances, but this effect fades away over the first ~200 y[ears].

In other words, as you approach 200 years, the risk of termination increases, but if you get past 200, the risk of termination flattens out. One of the effects of ageing is societies recover more slowly from disturbances. This is known in the systems literature as “critical slowing down”, and is seen across many different types of system:

Before a complex system undergoes a large-scale shift in structure, or a "tipping point", it often begins to recover more slowly from disturbances. The ageing human body is similar: injuries can take a longer toll when you're older.

The point is that “critical slowing down” is an indicator of loss of resilience. The article discusses two examples of this from the archaeological literature—neolithic farmers in Europe and the Pueblan societies in what is now the south-western United States. Taking the second of these:

The Pueblo societies were maize farmers who erected the largest non-earth buildings in the US and Canada before the metal-framed skyscrapers of Chicago in the 1800s. The Puebloans also underwent several cycles of growth and contraction, ending with crisis events in around AD700, 890, 1145, and 1285. During each of these events, population, maize, and urbanism fell, while violence rose. On average, these cycles took two centuries, in line with the wider pattern we found.

(Taos Pueblo building in New Mexico. Photo: John Mackenzie Burke, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In each cycle, recovery from crisis was slower than in the previous crisis.

Of course, there are some caveats here. One is the definition of a “state termination”. These take multiple forms, from a new ruling elite to a full-scale collapse, in which there is loss of government, written records, shared institutions, and population decline.

In addition, state termination may not be a bad thing. In some cases, state collapse led to greater prosperity for the majority:

Many pre-modern states were grossly unequal and predatory. By one calculation, the late western Roman Empire was three-quarters of the way towards the maximum level of wealth inequality that is theoretically possible (with one individual holding all the surplus wealth).

(By the same score, I’d note that the elite coup d’etat in England—later repackaged as the “Glorious Revolution”— that engineered the replacement of James II by William and Mary definitely led to an upturn for the English state.)

The numbers are also based on generally accepted start and end dates, which may not be completely reliable, given their distance in history. Even more recent state terminations can be problematic. Constantinople fell in 1453 to the Turks, but it was also partitioned in 1204 by marauding Crusaders. (I’d imagine they might both be terminations, although the 1453 one was rather more final.) The researchers deal with this by providing a range of estimates.

Their next steps in their research will be to examine the factors that create longevity.

States could be losing resilience over time due to variety of factors. Growing inequality, extractive institutions, and conflict between elites could heighten social friction over time. Environmental degradation could undermine the ecosystems that polities depend on. Perhaps the risk of disease and conflict rises as urban areas become more densely packed? Or loss of resilience may be due to a combination of different causes.

Depressingly, both extraction and environmental degradation are seen in the collapse literature as causes of collapse, along with over-complexity.

Of course, modern states are not the same as pre-modern states. They are more complex and more connected. But that may not reduce their vulnerability; it may just mean that they are at greater risk of collapse or termination from cascading systemic effects. We barely need to rehearse the litany of crises, from climate change to global wealth inequalities to failing planetary boundaries to the plethora of powers with nuclear weapons:

[T]he instability of a superpower, such as the US, could trigger a domino effect across borders. Both Covid-19 and the 2007-2008 global financial crisis have shown how interconnectivity can amplify shocks during times of crisis. We see this in many other complex systems.

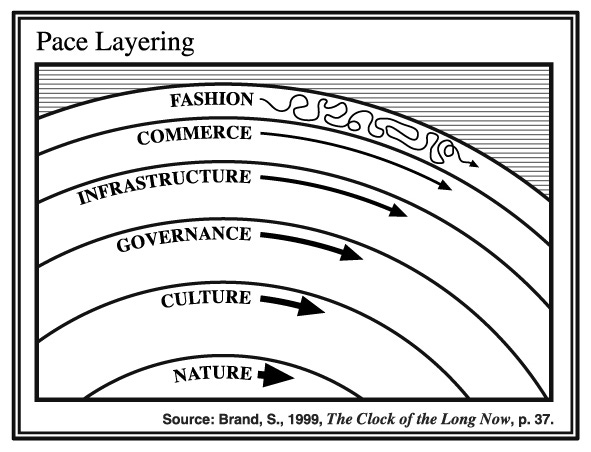

(Source: The Long Now Foundation)

But one of the things this research allows us to do is to attach a number to one of the layers in Stewart Brand’s pace layers model, which when discussed is largely conceptual. As a reminder, the top three layers are the ‘fast’ layers, the bottom three ‘slow’ layers.

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous... Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

In other words, the top three are sources of innovation, the bottom three sources of stability. Governance is the fourth layer down. We can assume now that the Governance layer has a clock speed of around 200 years.

The Collapse presentation can be downloaded here.

Other writing: music

From my contributions to the folk music site Salut! Live, a profile of the British “folk singer’s folk singer”, Wizz Jones. Here’s an extract and a song:

He’s played with everyone—the Facebook post mentioned among others Clive Palmer of Incredible String Band, Eric Clapton, Billy Connolly, Martin Carthy, Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and other assorted Pentanglers, even Sonic Youth. He’s helped to nudge people’s careers in the right direction: for example suggesting to the then Ralph May that he should take the stage name Ralph McTell.

j2t#604

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Some of the ranges in the Seshat database are higher because it covers older societies where the archeological and other temporal records are less reliable.