21 March 2024. Collapse | Creators

Understanding the idea of ‘collapse’ // Culture has become an extension of “Brand You” [#554]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Understanding the idea of ‘collapse’

I have an article on the literature on collapse in the latest edition of the APF newsletter Compass, which is all about different perspectives on collapse. Even if you’re not an APF member you can read the full edition in a version in Issuu on the APF website.

I’d thought about serialising it here, but it runs to three-and-a-half thousand words, and I think that’s more on collapse than all but the most committed futurist would want to read.

So I’m going to treat it as I would an article by someone else that is worth mentioning here, and pull out the good bits.

The starting point is that the whole discourse about collapse has changed in the quarter of a century I’ve been doing futures. When I started clients were hostile to the idea of a collapse scenario; now they expect it. There are some obvious reasons for this, from the financial crisis to the pandemic, and the ambient noise of climate change and biodiversity decline.

Collapse has a large and inter-disciplinary literature. There’s a literature review by Brozovic that identified 361 articles and 76 books. But what we mean by ‘collapse’ is a bit more disputed. Even the ‘collapse’ scenario that is one of Dator’s archetypes is sometimes described as a decline rather than a collapse:

There is little agreement about the speed of a collapse, or its distinguishing featiures, or its scale. According to the literature, collapse can happen at any scale, from villages to populations. It can happen at different speeds: the Mayan collapse, widely referenced in the literature, took 200-300 years. Nor is it clear why some collapse scenarios lead to collapse and others do not.

(Mayan civilisation took so long to ‘collapse’ they probably didn’t realise it was collapsing. Tikal ruins in Guatemala. Photo: chensiyuan, via Wikipedia. CC BY-SA 4.0)

There’s less disagreement about patterns of collapse. Ugo Bardi suggests that these include:

a ‘Hubbert curve’, a familiar bell curve;

a ‘Seneca curve’, in which the decline from the peak is vertiginous;

the ‘Lotke-Volterra curve, in which collapse in followed by recovery.

And there’s also a reasonable level of agreement that collapse is never mono-causal. Looking across the literature I identified four broad stories about collapse:

Collapse as a reduction in system complexity (Tainter);

Collapse as population overshoot and environmental failure (Diamond, Limits to Growth);

Collapse as failure of political economy, through extraction and status competition (Turchin);

Collapse as a step on the way to regeneration and renewal (Bardi, Homer-Dixon).

Of these, Tainter’s complexity theory is the most quoted, overshoot and collapse the most contested, extraction the most misunderstood, and regeneration the most recent.

1. Complexity

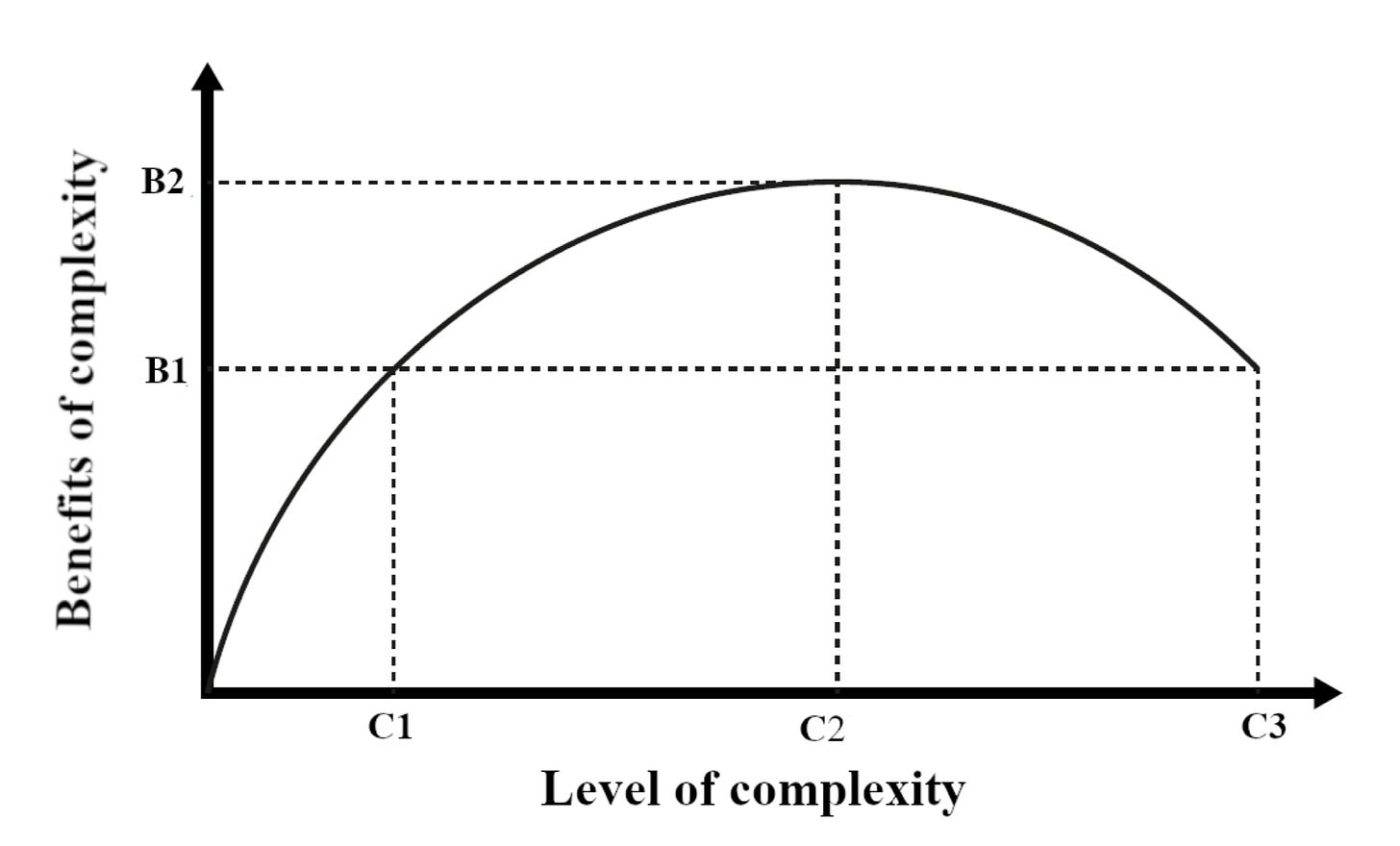

Tainter’s model, in short, is about the benefits and costs of complexity. Societies respond to problems by increasing their complexity (they might respond to water shortages, as the Romans did, by building irrigation systems). Initially, there are increasing returns to complexity—the rewards to society are greater than the costs. Later on, this is not the case. Complexity starts to produce diminishing marginal returns, and eventually the benefits of greater complexity are negative.

(Source: Bardi, Falsini, and Perissi, 2018. Redrawn from The Collapse of Complex Societies.)

Brunk argues that “human systems are self-organizing and societies tend to evolve toward the maximum level of complexity possible under current technological constraints.” One of the implications of this is that technology fixes to problems might not work.

2. Environment

The idea of ‘overshoot and collapse’ is at the heart of Limits to Growth, and the underlining model, simplified here, is that systems produce externalities that start initially to absorb effort and expenditure, and eventually drag the system to a halt. (I’ve written about recent assessments of the Limits to Growth model on Just Two Things before.)

(Jared) Diamond’s influential book Collapse also takes an environmental view of collapse, exploring it through case studies, some historic, some modern. He proposes a five-factor model of collapse: environmental damage; climate change; hostile neighbours; (less) friendly trade partners; and societal response to environmental problems.

But: every generation reflects its own concerns when it writes about collapse, so it’s not surprising that our collapse stories include environmental stories:

But there isn’t, as Diamond acknowledges, a single example where environmental issues have been the sole cause of collapse.

3. Extraction

Peter Turchin’s model of collapse is frequently referenced by doesn’t seem to me to be well understood. In End Times, he suggests that there are four structural drivers of instability:

popular immiseration leading to mass mobilization potential; elite overproduction resulting in intraelite conflict; failing fiscal health and weakened legitimacy of the state; and geopolitical factors.

In his model, the elite gains greater wealth because, typically the returns to labour decline, and the returns to wealth-holders increase. The most reliable predictor of crisis is intra-elite competition. This is seen in competition for public offices and access to elite education. However, the crisis can be a long time coming.

4. Regeneration

But: collapse is not usually an ending. So there’s a version of collapse that sees it as a necessary pre-condition to regeneration (as in the Panarchy model, for example). As Ugo Bardi argues:

Collapse is not a bug, it is a feature.

So this is more a story of resilience, about the capacity of a society to absorb shocks while also reorganising itself:

It can be the difference between a decline, or a soft landing, and a collapse, or a hard landing. One of the findings in the literature is that communities are more likely than not to hold together in the face of collapse.

Metaphors

Of course, the whole idea of ‘collapse’ is a metaphor. It implies a worldview:

It is embedded in notions of growth, ‘progress’, and ‘civilisation’. Collapse, on this reading, is the shadow side of the Enlightenment.

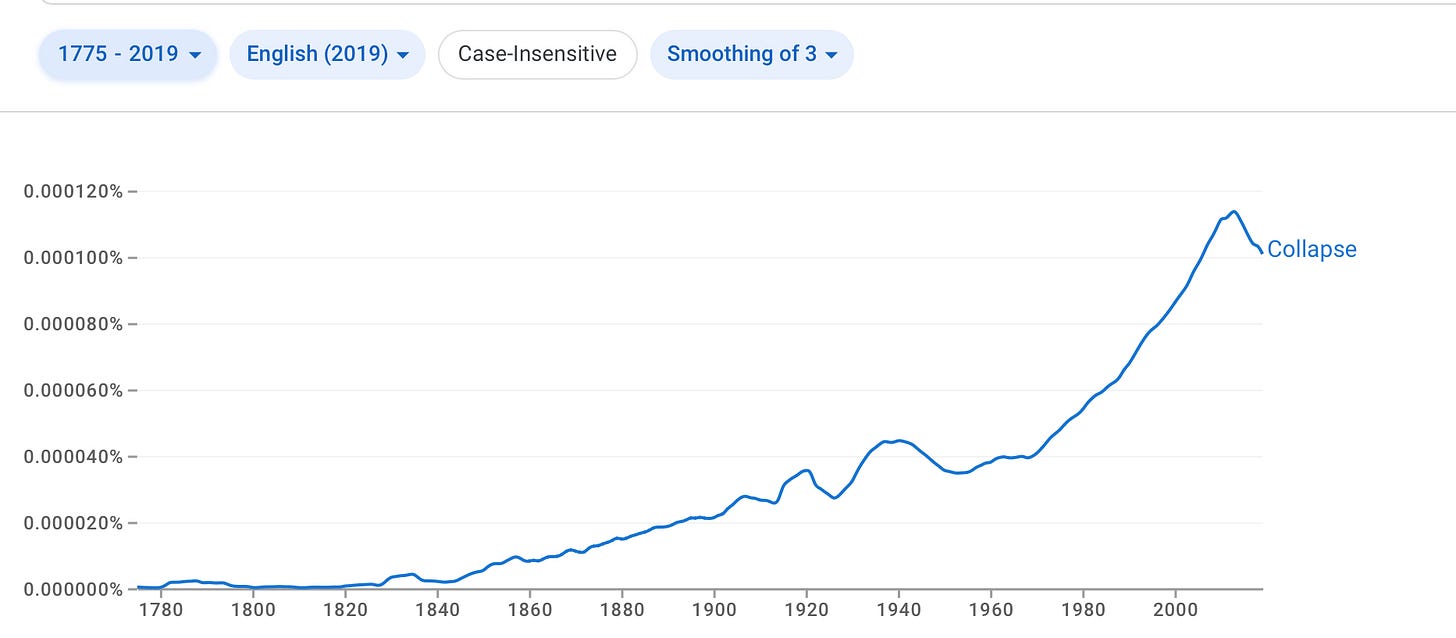

('Collapse’, 1775-2019. Google Ngram. Source: Curry: CC NC-BY-SA 4.0)

From this perspective, the Dark Mountain Project’s manifesto is an interesting document. It argued that:

The last taboo is the myth of civilisation. It is built upon the stories we have constructed about our genius, our indestructibility, our manifest destiny as a chosen species.

Dugald Hine evolved this thinking in his book At Work in the Ruins, which I have reviewed here, and which explores the issues raised for us by the end of modernity about collapse and regeneration.

What should we do in the face of all of this? There’s no shortage of examples through the literature about people being unwilling to respond, despite evidence of impending collapse (although Diamond definitely misrepresented the Easter Islanders).

Collapse isn’t a research problem: it’s an action problem. Indeed, Servigne and Stevens propose that it is an action research problem. But one of the things we need to do is to increase our capacity, now, for future response. Because collapse always involves a loss of capacity, just when you need it most.

You can read the full article as a pdf here.

2: Culture has become an extension of “Brand You”

I mentioned the idea of “Brand You” in a post last week, and that reminded me of a recent piece by Rebecca Jennings on Vox in which she argues that on the internet these days “you cannot escape the tyranny of your personal brand”:

For some, it looks like updating your LinkedIn connections whenever you get promoted; for others, it’s asking customers to give you five stars on Google Reviews. ... And for people who hope to publish a bestseller or release a hit record, it’s “building a platform” so that execs can use your existing audience to justify the costs of signing a new artist.

The piece is largely about the impact of all of this on people who make cultural products—music and books, mostly—where the publishing companies and record labels have more or less given up on marketing. That’s all down to the artist.

There’s a reason for this, of course. The dynamics of the platform businesses that now dominate cultural distribution are such that a writer or artist needs to make their own niche. The economics are less attractive than they used to be as well:

While Big Tech sites like Spotify claim they’re “democratizing” culture, they instead demand artists engage in double the labor to make a fraction of what they would have made under the old model. That labor amounts to constant self-promotion in the form of cheap trend-following, ever-changing posting strategies, and the nagging feeling that what you are really doing with your time is marketing, not art.

Of course, all of this relentless self-promotion isn’t much fun, and it also creates dissonance:

The labor of self-promotion or platform-building or audience-growing or whatever our tech overlords want us to call it is uncomfortable; it is by no means guaranteed to be effective; and it is inescapable unless you are very, very lucky.

(Source: Fast Company, 1997)

The idea of “the brand called you” first emerged in a 1997 Fast Company article by Tom Peters, and he later reworked it as a book (well, of course he did). Peters was ahead of his time—he’d identified that this was a likely consequence of the internet’s properties of cheap distribution. The thrust of the article was that the internet meant that everyone was in the business of branding:

It’s time for me — and you — to take a lesson from the big brands, a lesson that’s true for anyone who’s interested in what it takes to stand out and prosper in the new world of work... To be in business today, our most important job is to be head marketer for the brand called You.

He saw this as a liberating and an inevitable moment. Jennings argues that the economic changes we’ve seen over the last decade have driven the world in Peters’ direction:

Over the last decade, mass layoffs in supposedly stable industries, stagnant wages , and general disillusionment with corporate work have made entrepreneurship increasingly attractive to young people, who say they’d rather just be their own bosses.

Out there in cultural sectors, people are still buying books, but less of the money reaches the authors (which sounds to me like a problem of monopoly/oligopoly). People listen to more music than ever, but it is streamed and musicians see a fraction of the royalties they used to see. And in the wake of this, publications that used to review books and music are shrinking or folding.

Of course, the converse of all of this is that people who do strike it lucky online can do well for themselves:

Artists are scoring deals and record contracts based on their TikTok presences: a 27-year-old named Alex Aster sold the film rights to a YA book concept she’d pitched on TikTok before the book even published; the sea shanty guy got both a book and a record dealout of his brief viral moment.

This comes with its own issues. Jennings quotes Ricky Montgomery, a 30-year old musician with a substantial TikTok following whose career had been boosted by his own viral moment:

(E)ven when you land the record deal or have a few hit songs, you’re still stuck on the treadmill of constant self-promotion. “Next thing you know, it’s been three years and you’ve spent almost no time on your art,” he tells me. “You’re getting worse at it, but you’re becoming a great marketer for a product which is less and less good.”

There’s something here, in all of this, but some of it is profoundly ahistorical. Most writers have never made enough money to live on from books—long before the internet became mainstream in the early 2000s.

And the period in which musicians had a chance to make money from royalties is less than 50 years—from the arrival of the 45 rpm disc, through the ages of the LP and the CD. The music market was far more tightly controlled then. And even some of the successful musicians ended up deep in debt to their record companies (because the costs of production were much higher).

And outside of that, writers and musicians made a living either from patrons, or performing, or a bit of both. The critic William Deresiewicz, quoted by Jennings, also notes that in the post-war period the US state acted as a patron, through grants and fellowships at cultural institutions. The kinds of musicians who were never going to get rich from royalties are still making a living from performing, teaching, and bits of patronage.

But all of this might also just be further evidence that we’re getting closer to the end-state of neoliberalism. Jennings quotes the writer and activist Naomi Klein on the biggest change since she published her book No Logo in 1999:

“neoliberalism has created so much precarity that the commodification of the self is now seen as the only route to any kind of economic security.”

And as Jennings says, there are people who might see this as a good thing:

A society made up of human beings who have turned themselves into small businesses is basically the logical endpoint of free market capitalism, anyway. To achieve the current iteration of the American dream, you’ve got to shout into the digital void and tell everyone how great you are.

But societies have to be able to reproduce themselves if they are to be sustainable, and cultural reproduction is a necessary part of this. So for the rest of us, this is probably a reminder that if we care about culture, we should do what we can to help to nurture the cultural communities that we care about, and help the writers and artists and performers in them to try to make a living.

Other listening: futures

I was interviewed late last year about futures by Jacqueline Conway, who runs Waldencroft, a business that, broadly speaking, works in the area of executive and organisational development. For various reasons the release of the podcast was delayed until last week. Jacqueline was a knowledgeable interviewer, I think we covered a lot of ground, and the podcast runs to a manageable 49 minutes. You can listen to it here.

And here is Waldencroft’s ‘audiogram’ trailer for the longer interview.

j2t#554

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.