27 July 2024. Olympics | News

The Olympics as a media business // Most news is a non-event. How can we tell when it’s eventful? [#591]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open. And—have a good weekend.

1: The Olympics as a media business

Daniel Parris’ Stat Significant blog looks at the world through data, often topical data, and he marked the beginning of the Paris Games by looking at the revenues and audiences for the Olympics over time—the Olympics as a business, as it were.

(Paris 2024 Games logo, owned by Paris 2024 Organizing Comittee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games (POCOG (Paris2024)) for 2024 Summer Olympics.)

Because the International Olympic Committee [IOC] exists to ensure the continuation of the Summer and Winter Olympic Games, and that involves a lot of deals. As Parris summarises it:

it accomplishes [this] by monetizing broadcast rights, securing sponsorships, and licensing its brand. These lucrative partnerships fund training programs and athlete scholarships while covering the costs of organizing the Olympics.

How it does this is not a secret. I hadn’t realised this, but the IOC publishes a large marketing report in pursuit of these revenues. Parris has distilled this down to five main ingredients:

Broadcasting revenue, generated from selling exclusive media rights to television and digital platforms worldwide;

Sponsorship, through the Olympic Partner Progamme (which really is acronymmed as ‘TOP’)1, through which multinational corporations secure exclusive global sponsorship rights to the Olympic Games;

Domestic advertising partnerships, in which the host country negotiates local sponsorship deals;

Ticketing—the sale of tickets to Olympic events;

Licensing the Olympic brand for use in various products, including t-shirts, pins, and hats.

The revenues from the last three of this go to the host country, to offset the cost of staging the games. The first two are collected by the IOC.

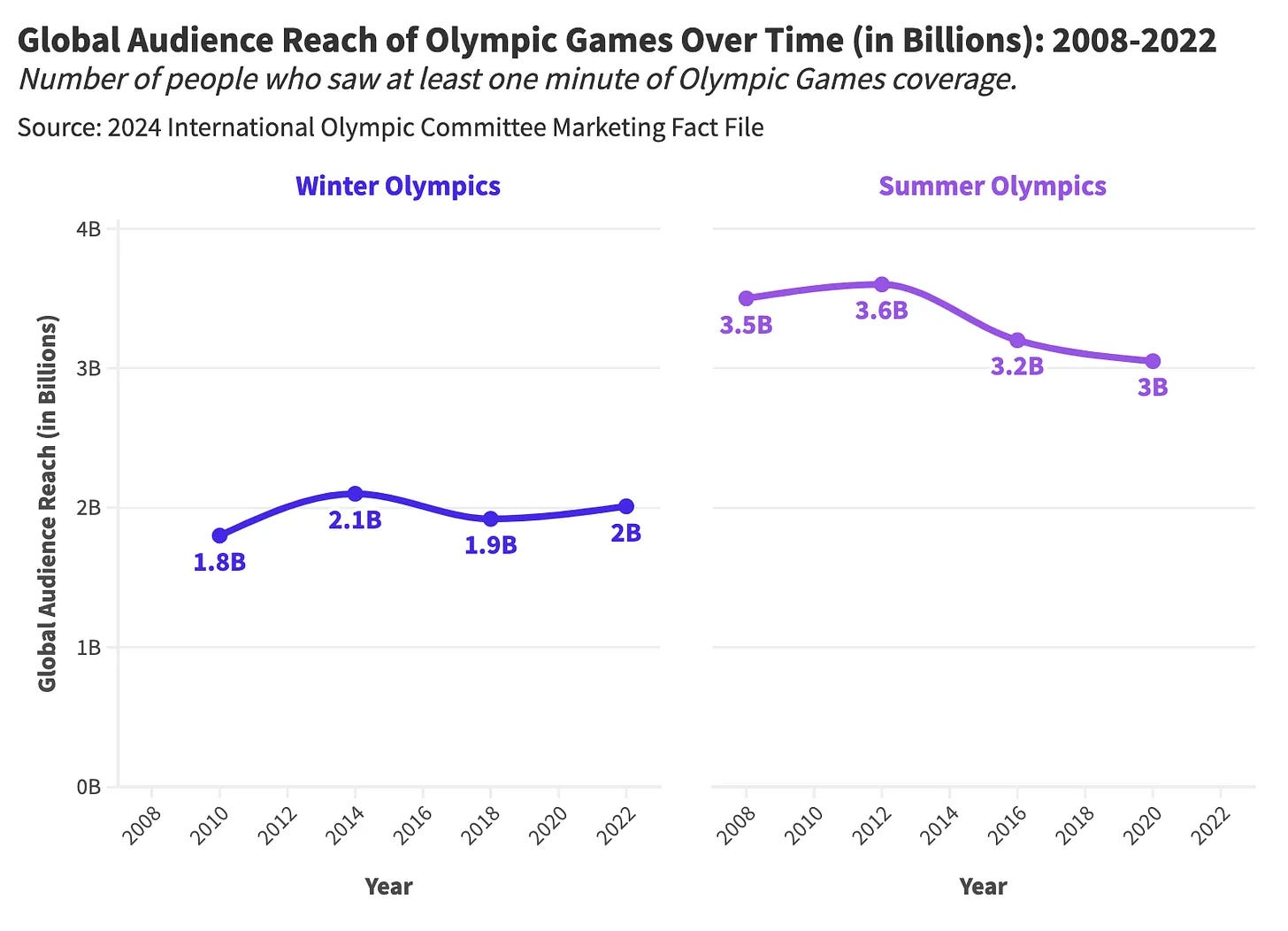

It turns out that viewing figures for the Olympics are more of less flat for the Winter Olympics, and have been heading downwards since 2012 for the Summer Olympics. When I say “viewing figures”, this is the data for people who have seen at least one minute of the Olympics on television.

(Source: 2024 International Olympic Committee Marketing Fact File)

Broadcasting revenue, on the other hand, has been trending upwards, while sponsorship revenues, both local and global, have been spiking sharply upwards.

(Source: 2024 International Olympic Committee Marketing Fact File)

Parris also notes that the IOC has been increasing the amount of available recorded coverage of the Games quite rapidly—there’s a chart in the piece—which suggests that the decline in summer games’ viewing is relatively speaking sharper than it seems at first sight. All of this seems paradoxical, but the Olympic Games turns out to be an exemplar of how media properties work in a fragmenting media landscape.

He summarises the story like this:

So, to recap, fewer people are watching the games despite increased coverage, and sponsors are willing to pay top dollar for diminishing levels of brand exposure. How is this possible?

These changes are likely adaptations to the increasing digitization of Olympics coverage—a phenomenon that has reduced the games' cultural footprint while (paradoxically) making them more significant.

There’s also data in the Olympic Fact File about the shift from broadcast viewing of the Olympics to viewing on digital platforms. Broadly speaking, these reversed between 2010 and 2022. In 2010, broadcast represented close to 60% of viewing and digital just above 40%. In 2022, digital is 60% and broadcast is 40%.

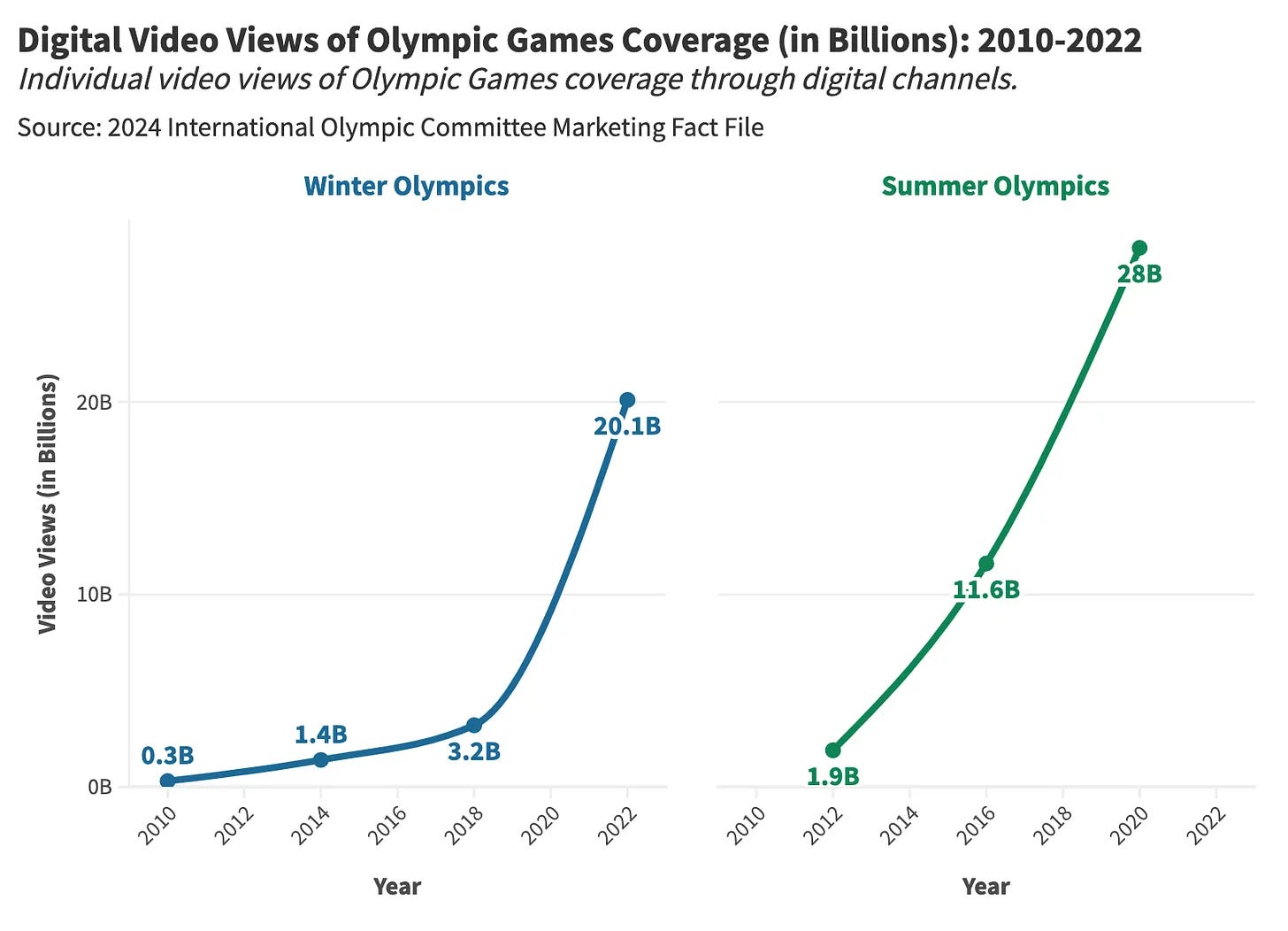

That seems like a steady trend, but the digital data is actually more dramatic in practice.

(Source: 2024 International Olympic Committee Marketing Fact File)

As Parris notes,

It's more common to watch a two-minute video of the winning gymnastics routine than to watch the gymnastics medal event in its entirety. For better or worse, the games now exist as a collection of moments—a highlight reel of athletic achievement. This phenomenon explains why broadcasting revenues are slowing, even as the IOC produces more content and sees increased partnership revenues.

But the important point here is that the Olympic remains the ‘brand wrapper’ for all of this content. The paradox isn’t really a paradox: as it becomes harder to reach people through broadcast television, brand owners end up paying more per view to any media property that can generate views and viewers.

The only event that comes close is the World Cup, although Parris has a misleading chart in his piece (not from the IOC Fact File) that compares the viewership of the Olympics to that for the World Cup Final, rather than any match in a particular World Cup competition.

He also suggests that the Olympics works better as moments. Even for the big athletics events—the 100m finals, say, or the 1500 metres finals—there’s a lot of hanging around in real time, while athletes get ready, announcements are made, there are false starts. There’s also quite a high chance of having to watch some handball or some rowing while you wait to go back to the athletics stadium.

In practice, most Olympic events don’t offer the same kind of narrative that you get from watching a knockout football match in the later stages of the World Cup or the Euros. As Parris suggests, iIn terms of our time, moments offer much better emotional value for our time. Digital works better for the IOC, and for the sponsors, in other words.

Olympics extra: Empire, masculinity and the invention of the Games

To mark the start of the Paris Games, the New Yorker shared a piece that it had published in 2012 by Louis Menaud on the origins of the modern Olympic movement. I’m just to going to pull out some notes from that.

I liked this piece because it made some of the Olympics strange by distancing it:

If someone described to you an ancient civilization in which, every four years, at great expense, citizens convened to watch a carefully selected group perform a series of meticulously preset routines, and in which the watching was thought of not as a duty but as a hugely anticipated and unambiguously pleasurable experience, you would guess that, socially, this ritual was doing a lot of work.

In summary, you would say, suggests Menaud, that the spectacle had some content, and so he asks,

What are we really watching when we watch the Olympics?

And you have to read between the lines a bit to get to his answer to this (and also read around an extended review of a couple of 2012 Olympic almanack type publications), but I’d say he thinks that the Games are a form of structuring device for a form of European nationalism that emerged in the 19th century.

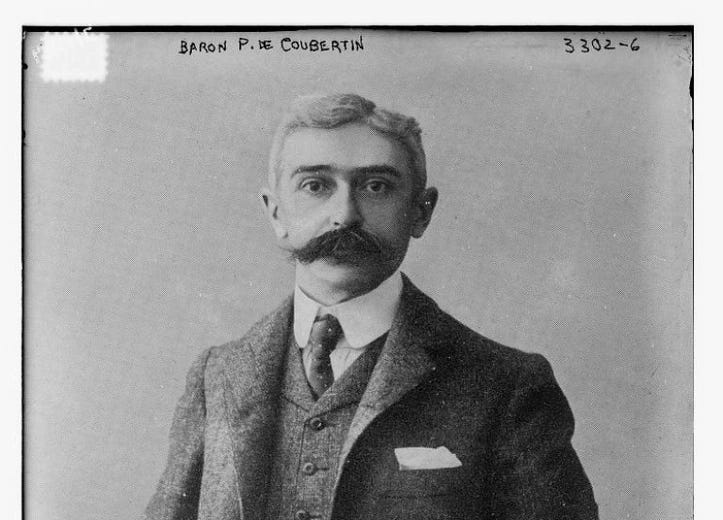

(Pierre de Coubertin. Photo: US Library of Congress.)

Many of our modern sports were developed in Great Britain in the 19th century, for example:

The British Open Championship in golf began in 1860, Association football championships in 1871, cricket championships in 1873. Lawn tennis was invented in 1873; Wimbledon started in 1877. The practice of commemorating the fiftieth and hundredth anniversaries of notable persons and events also dates from the late nineteenth century.

It took a while to standardise all of these, but once standardised, the British exported them fairly successfully. It’s amazing what you can do with an Empire and a large navy.

Pierre de Coubertin, who was French, not British, got interested in the early Olympics because he was concerned about the decline of masculinity in France. Although the Greek Olympics were the notional model, he visited the village of Much Wenlock, in Shropshire, which held an annual games.2 De Coubertin later wrote about it.

He wanted the French to be more manly, meaning more disciplined and self-reliant (he was reacting partly to the country’s defeat, in 1870, in the Franco-Prussian War), and he believed that introducing sports into education could be the basis for this transformation in the national character. In other words, he wanted the French to be more like the British.

In Much Wenlock, de Coubertin met the founder of their games, William Penny Brookes, who had founded them “as a way of fortifying British manhood”. De Coubertin concluded that sport was the basis of the British empire, and he quoted Brookes in his article:

“If the time should ever come when the youth of this country once again abandons the fortifying exercises of the gymnasium, the manly games, the outdoor sports that give health and life, in favor of effeminate and pacific amusements, know that that will mean the end of freedom, influence, strength, and prosperity for the whole empire.”

Brookes died just before the first 1896 games in Athens, and de Coubertin didn’t mention him much after that. But, suggests Menaud, the Games became a successful way to export European ideas to the world:

In 1896, the European imperial powers governed a large portion of the planet, and the Games were a tribute to their success in spreading their way of life—from the idea that life is essentially competition right down to the unit of measurement—throughout the world.

It’s not irrelevant here that de Coubertin was “a fanatical colonialist” who believed in the superiority of Europeans over other races. The Games, therefore, are also a form of “invented tradition”, in the concept developed by Hobsbawm and Ranger, wherein modern ideologies are masked by an overlay of the apparently historic.

2: Most news is a non-event. But how can we tell when it’s not?

Ian Leslie, who writes about culture and politics at his Ruffian blog, is better at culture than he is at politics. But in the wake of both the Trump assassination attempt and Biden’s withdrawal from the US Presidential race, he had an interesting column about the difference between events which weren’t consequential and those which were. He doesn’t do the piece any favours (but I’m sure he got more views) by headlining it

The Trump Shooting Was Fake News.

Although part of his newsletter is always behind a paywall, all of this particular argument is out in the open.

(AI image byMrMemer33 from the Twitch account TrumporBiden2024, via Wikipedia. ‘This file is in the public domain because it is the work of a computer algorithm or artificial intelligence and does not contain sufficient human authorship to support a copyright claim.’)

As a former journalist, I’m always interested in this kind of discussion. One of the reasons I ended up fatigued by journalism was that I thought that news wasn’t very good at distinguishing between what was important and what was the general procession of events. This has got much worse since then, with first the advent of 24 hour news and then ‘news’ on social media.

Of course, at the time of the attempted shooting of Trump, there were columnists who were willing to say that it had just won Trump the next election. So it’s worth explaining why Leslie thinks that it was not an eventful event.

On the morning that the news broke in Britain I posted a short thread arguing that this event probably didn’t make much difference to anything. My reasoning was not sophisticated. It was based on the psychological principle that almost everything that happens in life is less important than it seems when it is happening… and on the political principle that, well, this is America.

This is America. What he meant by this was that Trump was already a highly polarising figure in the United States: Leslie didn’t think anyone would change their minds about him as a result of the attempted shooting.

The voters who didn’t like him, or didn’t trust him enough to be president, would not suddenly be converted by a photo. People are really not that simple. The second reason is that the American news cycle is garish, melodramatic, and fast. Events leap out at you, shake you by the shoulders and immediately recede into a hazily recalled stream of crazy moments.

As he notes, the events at the Capitol on 6th January 2021 seemed shocking at the time, and were, I’d say, objectively shocking, but they haven’t proved to be politically impactful. (This may have something to do with the corruption of the US legal system by the Republican party, of course).

There’s a bit more here: the Iwo Jima style photos quickly gave way to the bandaged ear, which seems more reminiscent of the last days of Van Gogh or Jake Gittes in Chinatown; sad, or comic, but hard to take seriously. And there has been no sign of a poll bounce for Trump in the wake of the shooting attempt.

This, of course, raises the obvious question:

How do we distinguish between real news, by which I mean an important, game-changing event, and fake news, by which I mean an event that dominates headlines and social media feeds but isn’t actually significant?

The issue here is about distinguishing what’s important from what is not. Experts who live in a high-information environment turn out to be poor judges of this. We know this from Philip Tetlock’s work, but Leslie quotes some research that compared contemporaneous assessments of several years of US State Department diplomatic cables with later evaluation by historians.

The researchers compared this corpus to the fraction of the cables which were later deemed important by historians. Events that seemed important to the diplomats turned out not to be; events that seemed unimportant turned out to consequential. Even experts - perhaps especially experts - are highly unreliable judges of historical significance.

Leslie suggests that, in contrast to the Trump shooting attempt, the earlier debate between Biden and Trump was a consequential news event:

Although it has taken longer than I thought it would for Biden to fall, the first presidential debate really was as important as it seemed at the time. But there is good reason to think that was an exception rather than the norm. The debate didn’t actually shift public opinion much, if at all; it just made the Democratic Party’s power brokers unable to continue pretending they were blind to what everyone could see.

Sadly, he doesn’t suggest a model that helps us to distinguish between surface and depth: he only says that the debate was an exception. So I’m going to have a tentative stab at it instead.

I’d say that consequential news events are ones which articulate an underlying change of some kind, in such a way that it pulls the curtain away so we can speak of it. The Biden debate fiasco articulated the idea that there are limits to gerontocracy as an organising principle for society, just as the Grenfell Tower fire in the UK articulated the idea that endless outsourcing was unsafe for us all (see also sewage in our rivers).

This reminds me of the first two questions you ask yourself when you are scanning (I think these are courtesy of the futurist Wendy Schultz):

Does this confirm something we already know?

Does this change something we know?

We knew before the Trump shooting that America was a violent and gun-ridden country in which there was also a high level of violence towards politicians. It confirmed, it didn’t change.

But until the debate, the American gerontocracy seemed locked in as a ruling model. And suddenly we saw the limits of that. The curtain was pulled back and we couldn’t go on pretending any more.

j2t#591

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

Someone in the marketing department was definitely on fire that day.

This is why the 2012 London Games mascot was called Wenlock.