24 April 2024. Gamification | Curlews

All the world’s a game, and that’s not good // A new politics of nature [#564]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: All the world’s a game, and that’s not good

At Gurwinder’s blog, there’s a long long piece about gamification, and how it started out with good intentions but slowly got turned into something else.

He starts with BF Skinner’s experiments about behaviourism. Skinner started out on pigeons, but soon realised that his theories worked on humans as well:

Skinner’s three key insights — immediate rewards work better than delayed, unpredictable rewards work better than fixed, and conditioned rewards work better than primary — were found to also apply to humans, and in the 20th Century would be used by businesses to shape consumer behavior. From Frequent Flyer loyalty points to mystery toys in McDonalds Happy Meals, purchases were turned into games, spurring consumers to purchase more.

The American management consultant Charles Coonrandt wondered if these insights might work in the workplace, and found that they did. The problem with work, as he saw it, was that the feedback cycles were way too slow.

So Coonradt proposed shortening them by introducing daily targets, points systems, and leaderboards. These conditioned reinforcers would transform work from a series of monthly slogs into daily status games, in which employees competed to fulfil the company’s goals.

And then, of course, digital technologies became ubiquitous, and games became easier to manage. As Gurwinder notes there was a period in the 2000s when no conference was complete without a presentation on gamification. These, however, were mostly benign, typically a forerunner of the idea of ‘nudge’ which was popularised by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler towards the end of the decade.

(B)ack then gamification seemed to be mostly a force for good. In 2007, for instance, the online word quiz FreeRice gamified famine relief: for every correct answer, 10 grains of rice were given to the UN World Food Programme. Within six months it had already given away over 20 billion grains of rice.

Meanwhile, the SaaS company, Opower, had gamified going green. It turned eco-friendliness into a contest, showing each person how much energy they were using compared with their neighbors, and displaying a leaderboard of the top 10 least wasteful. The app has since saved over $3 billion worth of energy.

Fun seemed to be the way to change the world, and mostly for the better, it seemed:

if we could only create the right games, we could make humanity fitter, greener, kinder, smarter. We could repopulate forests and even cure cancers simply by making it fun.

(Seen in Soho, of course: London creatives at their finest. Photo: Andrew Curry CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

But, of course, there’s nothing in the world that the corporate mind can’t make worse. Humans are harder to manipulate than pigeons, it’s true, but on the other hand there’s so many more ways that you can manipulate them. In particular, there’s a whole group of incentives around respect and status that humans are particularly responsive to:

Will Storr, in his book The Status Game, charted the rise of game-playing in different cultures, and found that games have historically functioned to organize societies into hierarchies of competence, with score acting as a conditioned reinforcer of status. In other words, all games descend from status games.

This is one of the reasons why adding the ‘Like’ button was such an effective device for Facebook, and why every other social media platform, pretty much, followed them as quickly as they could. In China, this has become a “social credit” score—something they seem to have borrowed from Cory Doctorow’s satirical science fiction novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, in which citizens without a social credit of ‘whuffie’ no longer have access to social goods.

(As in the film Galaxy Quest, where the aliens have no concept of ‘fiction’, and don’t understand that the Star Trek-like series was made up, I sometimes wonder if a Chinese government official without a concept of satire read Doctorow’s book and missed the point.)

And some of our more unscrupulous employers have revisited Coonrandt’s work and realised how much that easier all of that is when you can track employees in real time:

Employers like Amazon and Disneyland use electronic tracking to keep score of employees’ work rates, often displaying them for all to see. Those who place high on the leaderboards can win prizes like virtual pets; those who fall below the minimum rate may be financially penalized.

It’s a long piece, and one of the reasons for this is that Gurwinder gets interested—probably over-interested—in gaming as part of the story of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, who killed himself in jail last year 25 years into a sentence of life without parole. It’s relevant, but not really central to Gurwinder’s thesis.

But as it heads towards its conclusion, it suggests that this is the reason we should be worried about gamification:

All the things a gamified world promises in the short term — pride, purpose, meaning, control, motivation, and happiness — it threatens in the long term. It has the power to seclude people from reality, and to rewrite their value systems so they prioritize the imaginary over the real, and the next moment over the rest of their lives.

But the problem with all of this is that the incentives of companies are misaligned with the needs of humans. (This isn’t the only area of human life where this is an issue at the moment).

Companies that exploit our gameplaying compulsion will have an edge over those who don’t, so every company that wishes to compete must gamify in ever more addictive ways, even though in the long term this harms everyone. As such, gamification is not just a fad; it’s the fate of a digital capitalist society. Anything that can be turned into a game sooner or later will be.

This might get worse if virtual reality takes hold, although I’m less worried about that than Gurwinder is. But he also believes that it’s possible to get by in a gamified world without being played by the system. His five tips here are:

choose long-term goals over short-term ones;

choose hard games over easy ones;

choose positive-sum games over zero-sum or negative-sum ones;

choose atelic games over telic ones;1

choose immeasurable rewards over measurable ones.

And maybe also take a tip from the poker player-turned-podcaster Liv Boeree:

“Intelligence is knowing how to win the game. Wisdom is knowing which game to play in the first place.”

H/T to Charles’ Arthur’s always excellent Overspill blog for the link.

2: A new politics of nature

It was World Curlew Day on Sunday, I learned from listening to Cerys Matthews’ Sunday radio show on 6 Music. It’s a grassroots kind of a ‘world day’, created by Mary Colwell in 2017 to draw attention to yet another species that is under threat.

The bird looks distinctive and has a very distinctive call:

One of the patrons of Curlew Action is David Gray, the musician (yes, Babylon, White Ladder, that David Gray), and he has been working with Mary Colwell to promote conservation initiatives for the curlew. Doing some quick research I found a blog post where the pair of them talked about their work:

MARY COLWELL: Curlews, for me, are the voice of Britain’s wild, wet, flowery, boggy and muddy places... They are sculptural birds, rounded and elongated with that wonderful, long downward curving bill. But they represent so much more. Curlews are what good looks like. If curlews are nesting safely, then so too are other ground nesting birds like lapwings, oystercatchers and skylarks. Curlews also represent insect and flower-rich meadows and peatland, the invertebrates in healthy, damp soils and in the mud of estuaries and wetlands.

Of course, they are under threat for all the usual reasons: unsustainable agriculture, insensitive afforestation, pollution, climate change, development, as well as predators like foxes and crows. She sees them as a belwether species: if the curlew is safe then nature and humans are living together better.

DAVID GRAY: In recent years I have begun to get more actively involved in efforts to protect and restore the natural world... For several reasons I have chosen to highlight the plight of the curlew in particular. First and foremost, it’s a truly unforgettable bird that has delighted and captivated me throughout my life... When the curlew opens its great curved bill to sing, it seems that we are listening to the very spirit of the wild land itself. I find it unthinkable that something as magical and irreplaceable as this could be lost within my lifetime.

Gray has been using music as a way to raise money for the cause, although I found this poem, ‘The Curlew’, written for him by a fund-raising anthology and read by him out in the wild, more affecting:

Some of this reminded me of a recent piece by the Guardian writer John Harris, who is consistently the most interesting writer on politics in the paper, probably because he lives outside of London and ignores all the metropolitan noise.

Harris argues in the article that we’re seeing a surge in the UK of a new politics of nature, probably a long time in the making but given new prominence by both the Right to Roam campaign and the vandalising of our rivers and coastal waters by water companies.

This is an interesting development, if true, since the British are much less connected to nature than our counterparts in Europe, although we delude ourselves about this:

the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences released a paper (in 2022) that measured fourteen European countries on three factors: biodiversity, wellbeing, and nature connectedness. Britain came last in every single category.

There are various theories as to why this is, but our much earlier urbanisation during the 19th century is sometimes suggested as a cause.

In the article Harris draws a thread between groups such as Muslim Hikers, Black Girls, and Right to Roam. Black Girls’ founder, Rhiane Fatinikun, has just been awarded an MBE; the Right to Roam campaign has been given an unexpected boost by its legal case in defence of wild camping against a hyper-wealthy Dartmoor landowner Alexander Darwall. The increase in outdoor walking during COVID may have helped:

In their very different ways, these stories centre on the same key ideas: a rejection of any idea of natural places and spaces being off limits, and the joyous democracy of gathering together to experience something more nourishing than concrete and tarmac.

He points, as well, to the kind of activism that mixes affinity with our landscapes and their histories with a harder edged politics. One of the things that is creeping in to British political discourse is the idea that nature might have rights, although of course that starts at the edges:

in Lewes in East Sussex last year, for example, the district council passed a motion that opened the way for the River Ouse being granted rights – to flow, be free from pollution and sustain native biodiversity – based on the Universal Declaration of River Rights created via international cooperation in 2017. Unsurprisingly, the political establishment does not like this stuff at all: earlier this year, the UK delegate to the UN environment assembly insisted that the rejection of rights for nature “is a fundamental principle for the UK and one from which we cannot deviate”.

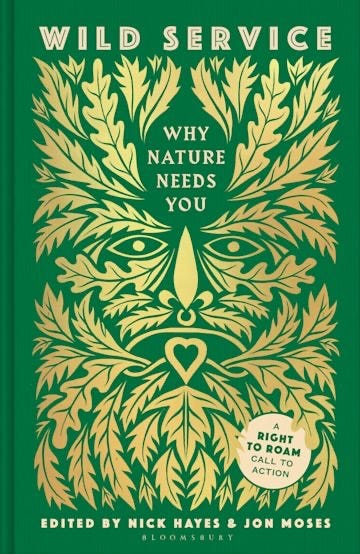

Well, one of the things you see in systems is that they are often at their most rigid just at the moment before they crack. Harris thinks that “A new kind of politics is brewing here”, and points to The Book of Trespass, by Right to Roam campaigner Nick Hayes as evidence of this, and a new collection, Wild Service—out this week—that Hayes has co-edited. (I wrote about Hayes and the Right to Roam in Just Two Things #137).

According to the publisher Wild Service

argues that humanity's loss and nature's need are two sides of the same story... (it) calls for mass reconnection to the land and a commitment to its restoration.

The book seems to connect ideas about art and science, culture and conservation, freedom and ownership, and some notions of ritual and the sacred. In The Guardian Patrick Barkham got quite excited about this—“a call to action that might just be the founding text for a new environmentalism”—and this also reminded me of the way in which the Dark Mountain Project centred culture in its framing of its understanding of the environment.

On 6 Music Cerys Matthews asked David Gray about the curlew’s call during her interview, and Gray became rhapsodic about what its loss would mean:

Places won’t be able to speak their wildness any more, the wind in the grass isn’t enough. When you hear the (curlew’s) call, you know that the land is speaking, you’re walking with your ancestors. The curlew is threaded through poetry, in WB Yeats, Ted Hughes.

And looking at John Harris’ article, I’m not sure that people would have been talking about conservation and bird species in this kind of language even a decade ago.

UPDATE: AI

I had a bit of a rant here last week ago about how AI—especially the “existential risk” school of AI—looked like a narrow discourse propagated by a very specific group of people (white, globally rich, male, etc), whose discussions were making a lot of noise and crowding out signal about more important things. So I have set myself as self-denying ordinance about not writing longer pieces on AI unless the point being discussed seems critically interesting. But I do think it’s still worth logging the significant discussions about AI, if only so they are easier to find.

In that spirit, a piece at The Conversation from the UCL Institute for Public Policy, by Mariana Mazzucato and other authors including Tim O’Reilly, starts from the premise that anticipating technology risks is largely a fool’s errand. But there’s one set of questions that it’s worth policy-makers spending time on:

These are risks stemming from misalignment between a company’s economic incentives to profit from its proprietary AI model in a particular way and society’s interests in how the AI model should be monetised and deployed.

This is not an abstract question:

It is instructive to consider how the algorithmic technologies that underpinned the aggregator platforms of old (think Amazon, Google and Facebook among others) initially deployed to benefit users, were eventually reprogrammed to increase profits for the platform... we investigated the role of algorithms, and the unique informational set-up of digital markets, in extracting so-called economic rents from users and producers on platforms.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, in a competition where everyone looks bad, Amazon comes out looking worst. This an academic version of Cory Doctorow’s enshittification thesis in action.:

User preferences were downgraded in algorithmic importance in favour of more profitable content. For social media platforms, this was addictive content to increase time spent on platform at any cost to user health. Meanwhile, the ultimate suppliers of value to their platform – the content creators, website owners and merchants – have had to hand over more of their returns to the platform owner.

In other AI news, from The Markdown: the water footprint of AI and its related technologies is absolutely terrible.

j2t#564

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

“Atelic games are those you play because you enjoy them. Telic games are those you play only to obtain a reward.”