Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story.

Apologies if you were expecting an issue of Just Two Things yesterday. Unfortunately I ran out of time to write it.

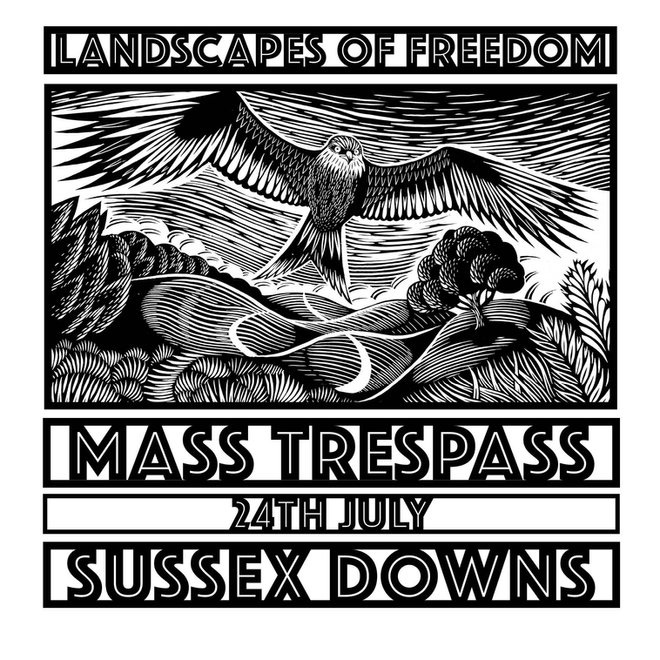

#1: A Right to Roam

I notice that there is to be a ‘mass trespass’ in Sussex, in the South of England, this weekend. It’s maybe a reminder that England is going through a ‘back to the 30s’ moment, but also an opportunity to write about the work of Nick Hayes, whose book on trespass—called The Book of Trespass—came out at the end of last year.

The mass trespass is in support of ‘free walking’, and in protest against the British Government’s Criminal Justice Bill, which would criminalise trespass in England. This is in sharp contrast with Scotland, which created a legal ‘Right to Roam’ after devolution.

Through free walking, we acknowledge the right of all people to access land which once belonged to everyone, and envision a society where the Right to Roam is a fundamentally respected freedom.

There’s a good interview with Hayes at the John Muir Trust, and I also heard Hayes talk on the RSA’s ‘Bridges to the Future’ podcast earlier this year (24 minutes).

The Book of Trespass uses the act of trespassing to step into the private, unacknowledged history of land enclosure in England. Ultimately, there can be no discussion of trespass without a history of the privatisation of common land and commonwealth, without talking about other issues in the Land Rights agenda, such as Land Value Tax or a community's right to buy. When Scotland passed the Land Reform Act in 2003, it opened up the majority of land and water to public access, but it also created a structure for a community's right to purchase land in common ownership. So the issue of access and ownership are intrinsically linked.

The rights to rivers, it turns out, are even more fragile than the rights to land in England.

Because you can only do so much with a campaign, The Right To Roam is concentrating on the right to access, because it’s the most urgent thing to do. As we’ve seen during the pandemic it’s also the thing that has the most immediate impact on health and wellbeing.

During lockdown, those with access to space - whether back garden or hillside - were undeniably more privileged than those locked down in inner city areas. People were more aware than ever how desperately our bodies need to be outside and subsequently how unfair the division of land and space is in our country. The Sunday Times found that if golf courses were opened to the English public, one million people would have easy access to open space.

Of course, England was one of the first countries in the world to expropriate land at scale from the people. (They’d done it more brutally earlier in Scotland, which is one of the reasons why Scottish land law is more progressive). Hayes is good on the way the long shadow of this makes the reasonable demand of the Right to Roam seem like something that needs to be justified.

Up until 1832, you could only qualify to be an MP if you owned substantial land holdings. The entire architecture of law was constructed with a bias toward land holders, even though historically most of the population have owned very little, if any land at all.

We look at a wall in nature as if it possesses an authority, as if our exclusion is justified. But just a quick breeze through the history of how it came to be built, and a catalogue of exploitation, dispossession and community division entirely undermines the wall's legitimacy.

#2: Moon trees

There’s a delightful short piece by Natalie Middleton at Orion Magazine on the strange tale of the Douglas Fir seeds that were sent into space by NASA—and what happened when they came back to earth.

The fact is, the experiment didn’t go well.

They eventually completed the longest journey ever made by seeds and touched down back on Earth. On landing in the South Pacific, the canister was held for the first time since it had been packed. The plan was to clean it, plant the seeds, and witness how being carried so far from their habitat might affect their growth. But the decontamination chamber ruptured the seal on the canister, spraying the seeds in an explosion they were assumed not to survive.

(Image: NASA)

Despite this, NASA followed through with the experiment. They sorted through the ‘moon seeds’ and sent them out to greenhouses in California and Mississippi, where they were planted, more in hope than expectation. 400 of them grew into trees and were re-planted across America, and elsewhere:

Some were installed on the grounds of historic buildings, including the White House; others took root in neighborhoods—in front of a public library, a junior high, a hospital, a cemetery. Most were left unmarked, destined to flourish anonymously, far outliving the astronauts who first brought them into the skies.

The article comes with a terrific interactive graphic that shows the location of the trees now.

j2t#137

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.