22 April 2024. Boeing | Wealth, pt 2

The ‘phenomenally talented assholes’ Boeing fired for caring about safety // Dealing with the super-rich (part 2). [#563]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The ‘phenomenally talented assholes’ Boeing fired for caring about safety

I wrote earlier this year about how Boeing was transformed from an engineering leader to a “shareholder value” company, with consequences for the safety of its planes. At the American Prospect Maureen Tkacik tells the story of John Barnett, a Boeing quality engineer who went from being marginalised to being fired to becoming a whistleblower.

I was just going to do a quick update here, but then I started reading the article properly, and it is fascinating.

“John is very knowledgeable almost to a fault, as it gets in the way at times when issues arise,” the boss wrote in one of his withering performance reviews, downgrading Barnett’s rating from a 40 all the way to a 15 in an assessment that cast the 26-year quality manager, who was known as “Swampy” for his easy Louisiana drawl, as an anal-retentive prick whose pedantry was antagonizing his colleagues.

(John “Swampy” Barnett at Boeing, centre. Photo by his brother Rodney Barnett, via American Prospect)

This wasn’t a one-off, but a pattern. The company was trying to get rid of engineers like Barnett, who were concerned about quality and safety.

CEO Jim McNerney, who joined Boeing in 2005, had last helmed 3M, where management as he saw it had “overvalued experience and undervalued leadership” before he purged the veterans into early retirement... “Prince Jim”—as some long-timers used to call him—repeatedly invoked a slur for longtime engineers and skilled machinists in the obligatory vanity “leadership” book he co-wrote.

The phrase McNerney used in his book for these engineers—who were more interested in the integrity of the planes than the stock price—was “phenomenally talented assholes.” (“Vanity book”? It’s called You Can't Order Change: Lessons from Jim McNerney's Turnaround at Boeing.) Boeing had a personnel strategy to ostracise these managers so they decided to leave.

(McNerney) initially refused to let nearly any of these talented assholes work on the 787 Dreamliner, instead outsourcing the vast majority of the development and engineering design of the brand-new, revolutionary wide-body jet to suppliers, many of which lacked engineering departments. The plan would save money while busting unions, a win-win, he promised investors. (Emphasis in original).

Did it work? No. The plan went $50 billion over budget. Boeing had to buy out, and then bail out, at least one of these suppliers, and some of its customers, such as Qatar Airlines, refused to accept the planes because of the level of faults. I was going to say that Maureen Tkacik’s article reads like a chronicle of a death foretold, but that’s an unintended and somewhat grim pun.

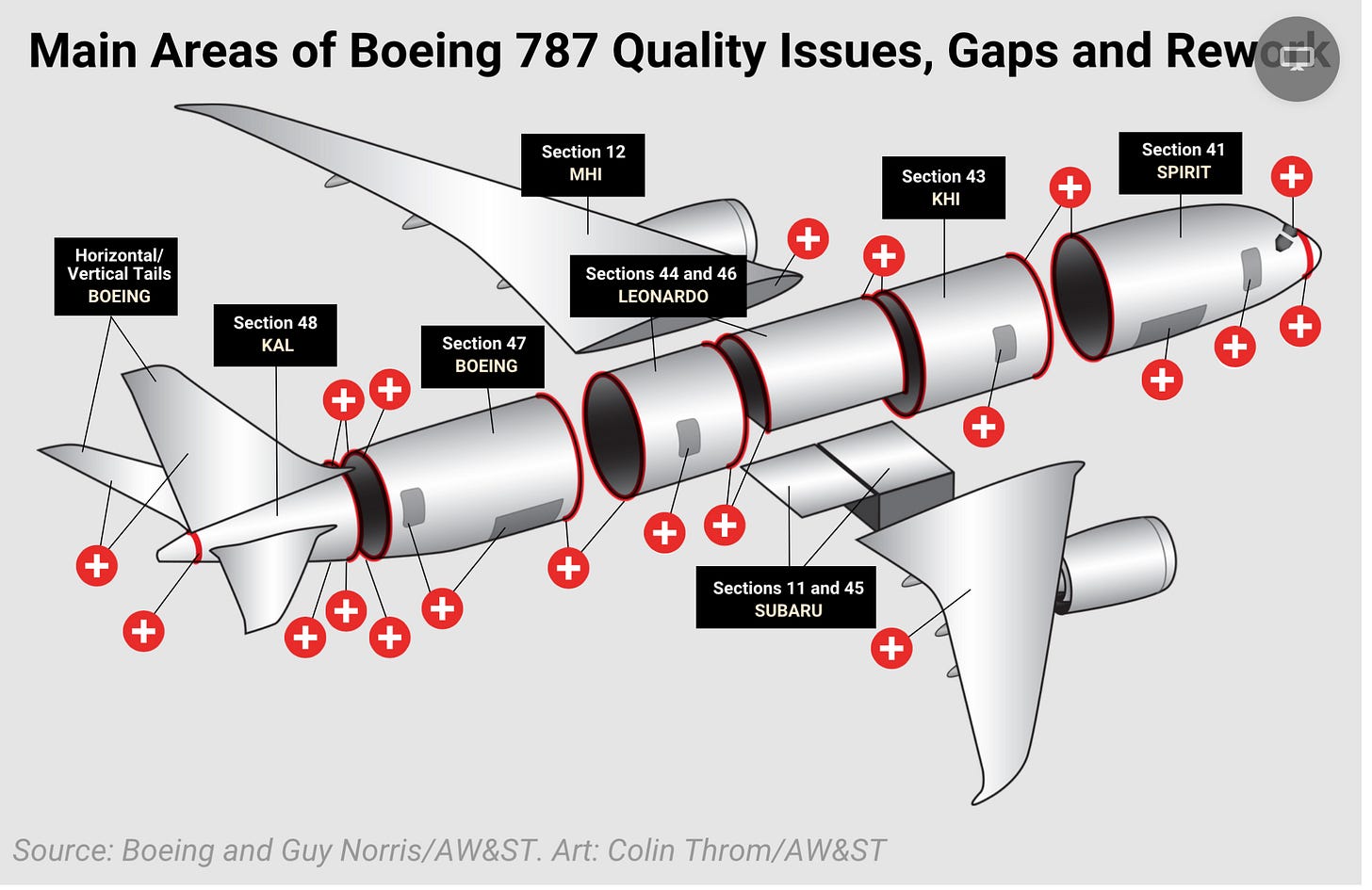

When the 787 was finally grounded by the Federal Aviation Authority, Aviation Week published a helpful diagram showing the places where investigators were finding quality problems: everywhere.

(Aviation Week)

At around the same time, the Wall Street Journal headlined a story on Boeing,

Boeing Looked for Flaws in Its Dreamliner and Couldn’t Stop Finding Them.

Barnett had been a member of one Boeing’s “clean up crews”, detailed to address quality problems and fix them. But by the time the Dreamliner was grounded all of the people with that kind of expertise had been hounded out of the company, in defence of the stock price. I think this is an example of being careful what you wish for.

Stan Sorscher, who had been a longtime Boeing physicist and former officer of SPEEA, the labor union representing Boeing engineers, told Tkacik,

“For every new plane you put up into the sky there are about 20,000 problems you need to solve, and for a long time we used to say Boeing’s core competency was piling people and money on top of a problem until they crushed it.”

Not any more. One of the problems that Boeing had was that its leadership pursued a merger with MacDonnell Douglas in the late ‘90s, and then found that MacDonnell Douglas’ cost-driven culture destroyed Boeing’s culture of technical excellence. This was why engineers like John Barnett found themselves in the firing line. Yet before the merger MacDonnell Douglas had done a study that found that less experienced staff were significantly less productive than more experienced staff:

McDonnell Douglas managers published a statistical analysis in 1997 gauging productivity against the average seniority of managers across various programs that found that greener [less experienced] workforces were substantially less productive, which he found to be a “mirror image” of a kind of “rule of thumb” within Boeing that held that every Boeing employee takes four years to become “fully productive.”

The average employee who worked on the 777 had between 15 and 20 years experience, whereas the average employee who worked on the 737 (the one with the software kludge that caused it to crash twice before it was grounded) had five years experience.

Just to spell this out, the Boeing management’s hounding of its experienced employees would have been economically counter-productive even without the vast costs incurred by crashes, groundings, and FAA investigations.

As of today,

hundreds of Boeing 737 MAXes sit in abandoned parking lots [in California and Washington State] waiting for someone to fix them so they can finally be delivered. Meanwhile, pieces are flying off the Boeing planes actually in use at an alarming rate, criminal investigations are under way, and another in a long line of stock-conscious CEOs is stepping down. Boeing’s largest union, the Machinists, is trying to snag a board seat because, in the words of its local president, “we have to save this company from itself.”

What happened to John Barnett—to “Swampy”? He was found dead a few weeks ago with a gunshot wound to his right temple, a death that may, or may not, have been suicide. It was on the morning of “the third day of a three-day deposition in his whistleblower case against his former employer”. The trial was scheduled for June. The deposition, since released by his lawyer, forms the basis for much of the American Prospect story.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the circumstances, his co-workers are sceptical that he killed himself:

One former co-worker who was terrified of speaking publicly went out of their way to tell me that they weren’t suicidal. “If I show up dead anytime soon, even if it’s a car accident or something, I’m a safe driver, please be on the lookout for foul play.”

In an earlier piece, Maureen Tkacik was sceptical of the “foul play” thesis, even if Barnett’s lawyer and brother were clear that he showed no signs of being suicidal:

I personally have trouble believing Boeing would plot a whistleblower murder, mostly because there are dozens of internal whistleblowers where Swampy came from, and it would be impractical to kill all of them, especially given that Boeing has thus far enjoyed exceptional impunity without bringing about the mysterious death of any crucial witnesses.

But it’s also worth noting that the regulatory and judicial heat is suddenly on Boeing, as a result of the recent Alaska fuselage blow-out, and at the heart of this is an issue about the company’s policy from the “shareholder value” management years of ‘non-documentation’ of faults. John Barnett knew more about non-documentation than anyone, and had recorded it in vast detail. Because one of the lessons of being an effective whistle-blower is that you have to keep everything.

.

2: Dealing with the super-rich (Part 2)

This is part two of a post from the launch of Luke Hildyard’s book Enough at an event organised by the High Pay Centre, where he is Director. Panellists at the event included the academic Andy Summers, of LSE, the communications specialist Dora Meade, of NEON, and the journalist and Labour Party candidate Yuan Yang.

The basic case against the super-rich is three-fold. One, they are bad for the economy, because they spend less of their money, and what they do spend goes on things that aren’t good for us (plane flights, for example). Two, they are bad for society, because money and wealth that is captured by the super-rich is less money to pay people living wages, or invest in public goods. Three, they are bad for politics, because they load democracy in ways that is good for them, and not so good for everyone else. (Even when they do give it away, it comes with values at odds with public values.)

It’s also not a zero-sum game. The policies that would change this situation for the better would almost certainly increase incomes and wealth overall. That’s certainly the lesson from elsewhere:

prosperous countries like Norway or the Netherlands have achieved both higher overall prosperity and much lower overall inequality suggests it should be possible to achieve this in other countries too.

The policy story is pretty clear. Both the UK and the US suffer from extremes of private affluence and increasing public squalor, to paraphrase JK Galbraith. But because we’ve lived through a forty year period in both countries where being “intensely relaxed” about wealth accumulation has been the main organising principle of politics and the economy, we’ve had time for lots of stories to be created as to why changing any of this would be A Bad Thing.

(The Rich Are Always With Us (1932). Source.)

In his talk to launch his book Enough, which I also discussed last week, Luke Hildyard addressed some of these stories.

The first, which I discussed in Part 1, is that most wealth is not earned, it’s transferred. As Hildyard said, the best way to be super-rich is to be an heir or and heiress (and this is generally true of having access to wealth), or to have a family member who knew Vladimir Putin in the 2000s. Or the Duke of Grosvenor’s advice to young entrepreneurs:1

Make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend with William the Conqueror.

Much the same is true of high income: there is a very weak relationship between high executive pay, and business performance. Company Remuneration Committees claim they pay millions to CEOs because they have to be internationally competitive, but the track record of CEOs of British companies going to the US and doing well is almost zero. The research says that high performance and productivity tends to be driven by investment, culture and organisational design, not individuals.

This myth about high earners comes with another one in tow: if we taxed wealth and high incomes more, the super-rich would all leave. That might not actually matter much, but in any case, they probably wouldn’t.

At the High Pay Centre event, Andy Summers referenced some qualitative research with the wealthy that the LSE had done. Despite the idea that the wealthy were very mobile, in practice they didn’t choose where to live by assessing marginal tax rates. One person told them, “We considered Switzerland, but it’s too boring.” In the interviews, people were also disparaging of their peers who chose to move to low tax jurisdictions.

Hildyard finished his remarks by saying that you needed a mix of predistribution and redistribution to make this change happen, that it would be good for growth (and productivity too, I suspect), and that he saw it as a centrist agenda, not a radical one.

Dora Meade, who specialises in progressive communications, spent some time on how to change the discourse on taxing the super-rich. There are a couple of obstacles here. The first is that the idea of “meritocracy” is more strongly embedded in the British mindset than in other countries, and that comes with the idea that wealth is deserved.2 One of the agenda items here is to break that idea; Meade suggested that just “punching up” wouldn’t work.

The second is that people don’t have a good idea of how much tax is actually paid on wealth. Inheritance tax, for example, has a marginal rate of 40%, but an effective tax rate of 10%.

She thought it was worth telling a story about the shared nature of wealth creation, and drawing a clear line between the “us” who create wealth and then “them” who extract it. (This reminded me of Obama’s 2012 campaign speech, “you didn’t build that”, which also comes with a story attached to it about the public and social infrastructure that underpins every business—roads, schools, health care, utilities.)

This could be tied to a story about “deserved” and “undeserved” wealth:

What’s the biggest version of ‘we’ can wrap around this story?’

Yuan Yang mentioned talking to prospective constituents in a reasonably prosperous area of Reading, in southern England, and finding

a huge amount of resentment about how elites have failed the country, with concerns about how to pay for services;

a fear that taxing wealth means taxing them;

resentment that politicians are in it for themselves and the rules of the game are broken.

She’s found that fairness works as an argument — for example talking about the way the rich benefitted from Quantitative Easing while the poor got punished by austerity. Talking about those members of the super-rich (the “Patriotic Millionaires”) who want to contribute to society also helps.

Some of this might also involve being clearer about income levels. The UK’s median income—the 50th percentile—last year was £32,300. Anyone earning more than £100,000 a year is in the top 4% of earners.

Median household wealth is around £300,000, and the top 1% have wealth of £3.6 million. The top 5% mark is around £2 million.

There are also some innovative approaches to this, as I discovered doing some research afterwards.

(Source: Wealth Tax Commission.)

Summers was one of the authors of the Wealth Tax Commission report, which recommended a one-off wealth tax that ran for five years at a rate of 1%. There’s some small print here, but this is the key finding:

After accounting for non-compliance and administration costs, a one-off wealth tax payable on all individual wealth above £500,000 and charged at 1% a year for five years would raise £260 billion; at a threshold of £2 million it would raise £80 billion.

I might go for the higher threshold, which takes in only the top five percent, and up the rate to three or four percent—which on the trends over the last decade would at least rake off some of the gains to wealth and put them to public use. Raising this amount in any other way (income tax, VAT etc) involves huge increases in tax rates.

I also found the the idea of the “lifetime income supertax”, which uplifts your tax rate once you’d earned more lifetime income than, say, someone who spent 40 years earning at the 90th income percentile (£66,700 in 2023, so lifetime earnings of £2.67m). That would also require wealth taxes like capital gains taxes to be (at least) equalised with income tax.

Enough is a short book, and it synthesises the evidence well. The argument is broken up with useful crossheads. I recommend it if you’re interested in abolishing the super-rich. You can read the first chapter here. It’s also worth looking at Richard Murphy’s Taxing Wealth Report 2024, which looks at some of the numbers around taxing wealth.

Post script

After Part 1 of this piece appeared on Saturday, my SOIF colleague Lewis Lloyd sent me a link to a simple online game in which you inadvertently get hold of all of Jeff Bezos’ money and get the chance to spend it.

“You are Jeff Bezo$” was written by Kris Lorischild. I enjoyed it, even though it is really hard to spend all his monry. If you have a go, do buy them a coffee afterwards.

j2t#563

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

The Grosvenors own much of the most valuable real estate in central London.

Although only 4% of CEOs in the UK are founder-CEOs.