27 February 2024. Gates | Cattle

The problem with billionaire philanthropy // The grim world of live cattle transport ships. [#546]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

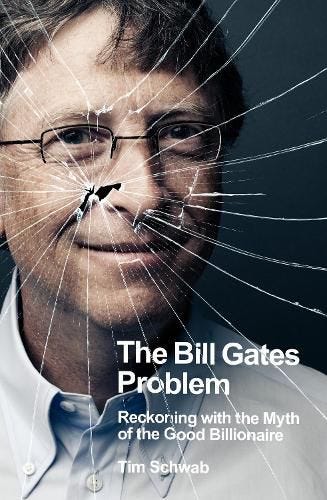

1: The problem with billionaire philanthropy

At Alliance Magazine Deborah Doane has a longish review of Tim Schwab’s book The Bill Gates Problem. It’s always good when a book spells out its position in the title, but the Bill Gates problem, in a nutshell, is this:

Schwab reveals Gates’ influence across public health, journalism, vaccinations, the pharmaceutical industry, agriculture and even women’s lives in global majority countries. All of these have one primary thing in common toward recreating these sectors in the same way he put his stamp on Microsoft: an ideological adherence to trickle-down economics, controlling markets in a monopolistic fashion and avoiding scrutiny.

The sub-title of Schwab’s book spells out even more clearly:

Reckoning with the myth of the good billionaire.

Philanthropy, of course, is the outcome of an economic system in which the rewards to some individuals are disproportionately high. As Doane says, when you take philanthropic money you know this but

you close your eyes to the origins of the funding and even the decision-making models and try to accept that the outcomes are more important than the means.

Schwab’s book, she says, makes it harder to do this. For one thing, philanthropy is a way to pay less tax. Billionaires are

actually being subsidised by the state for their philanthropy through tax breaks and complex organisational accounting practiced by the likes of the multi-national companies that they once presided over. They have effectively privatised public goods and shaped charity to fit with their own world view.

And the problem with that worldview is that it is essentially a neo-colonial worldview. Schwab finds over and again that the solutions that Gates (and other Global North philanthropy) proposes are technology-led solutions that disable their recipients. For example:

In Chapter 13, Schwab provides the example of Gates’ ambition to introduce GMOs to Africa, and to industrialize farming using western-led technology. ‘The premise of the Gates Foundation’s work is that African nations don’t have the expertise or capacity or tools to manage their own food systems – that they need professionals and experts from the Global North to help them.’

That’s an initiative that hasn’t worked out well, of course. Since the AGRA (Green Revolution) programme was introduced in 2006, the number of undernourished people in the 13 countries where it operates has increased by 30%. That figure is from a letter from African organisations more or less asking Gates to close the programme, but Scientific American is also sceptical on the programmes outcomes.

Deborah Doane has worked in this area, and she notes that GMO technology tended not to be the best solution:

in my own work on the food system, some years ago, with Fairtrade producers in India, it was widely proven that farmers who prioritised organic, local seeds through mixed farming methods, alongside fair access to markets, were far more resilient and productive than those who had been offered GMO technology.

It’s noticeable that the Gates Foundation hasn’t signed the donor pledge co-ordinated by USAID agreeing to prioritise locally-led development. But that doesn’t stop its influence being everywhere, perhaps because it spends billions in and around Washington on newsrooms, policy think tanks, and lobbyists—more, in fact, than it spends in Africa.

The Gates Foundation has also majored in the importance of evidence, and there are claims about impact all over its literature and news releases. Schwab says that many of these are rooted in dubious narratives about cause and effect, and they hard to verify:

none of these statistics are verifiable through independent sources because of the unaccountable nature of the organisation. The lack of scrutiny is ensured for anyone wanting to engage in Gates, as staff, affiliates, contractors and grantees all have to sign non-disclosure agreements that threaten anything they say externally, even long after they have left the organisation.

But it’s not just about Gates. A lot of these problems extend into billionaire-led philanthropy more widely.

Schwab touches throughout on the unaccountable nature of philanthropy, noting that of 100,000 foundations in the US alone, only 200 per year are ever audited. And that the rules of the game haven’t changed since the 1960s.

There are some technical things that can be done about this. For example there is pressure in the US to make foundations draw down their endowments faster, rather than amassing capital, and there are also calls for boards that are independent of the founders and more representative of the intended beneficiaries.

Of course, as others have argued, Schwab thinks that it would be better to tax wealth more effectively rather than have it used as a way to protect one’s wealth and influence. Zuckerberg’s Limited Liability entities, set up to give away his money, is even more opaque than the Gates Foundation.

Either way, foundations, and the extreme wealth that sits behind them, are not good for us, says Schwab in the book:

‘As long as Bill Gates maintains his extreme wealth, he will remain a canker on democracy.’ ‘If not through his private foundation, then through other means.’

Doane works in this space, and she suggests that this is an important book even if you don’t:

Schwab’s book is a must-read for any of us who are working in this sector, anyone who regulates the sector and anyone who cares about equality. Even if we haven’t received Gates’ funding directly, we will have been influenced by their work through some means or other.X

2: The grim world of live cattle transport ships

The South African paper the Daily Maverick has a story by Don Pinnock about the completely inhumane practice of transporting live farm animals by sea to their eventual market, in terrible conditions. Many of them die.

And this is a grim account—please don’t read it if you are having breakfast.

It was one of those things that I hadn’t thought about until I read their article, and there is no real reason that the trade exists at all. The prompt for the piece was the arrival of such a ship in Cape Town earlier this month with

20,000 cattle standing and lying in a sea of their own excrement were in a huge ship docked in the harbour.

The piece draws on the work of the vet Lynn Simpson, who used to work on such ships on behalf of the Australian government. Eventually her reports of conditions on board the ship became “too graphic”, and she was fired. She now runs a blog documenting the cruelties of shipping live animals. It doesn’t make easy reading.

There are some extracts in the Daily Maverick article:

“Dead animals were lifted into a wheelbarrow and pushed up or down a ramp to the few exit points. If the animal was decomposing rapidly they would be delicate to move without making them fall apart or explode, degassing internal build-up.

“The men on this voyage utilised empty chaff bags to fill with bits of body and then shovels to fill the barrows with fluid discharge and abdominal contents. The bags would seep with body fluids and be reused until worn out.”

It is a huge trade. The Guardian has estimated that some two billion animals a year get shipped like this.

(Still from a recent investigation by ORF. Source: Animal Welfare Foundation.)

The rationale for the trade, mostly to Muslim countries, is that animals need to be slaughtered in line with Halaal practice. According to the article this doesn’t stand up.

Other animals that are to be exported for meat are killed close to where they are grown, and then frozen for export. There is nothing to stop animals intended for Halaal consumption being killed according to Halaal principles in their country of origin.

It’s worse than this: shipping animals in these degrading conditions is itself a breach of Halaal principles:

The director of South Africa’s Muslim Judicial Council Halaal Trust, Shaykh Achmat Sedick, has in the past spoken out against the live export, questioning how the government could permit the shipping of tens of thousands of animals to the Middle East. He said these animals would not have had “tay-yib”, which means wholesome and humane treatment.

Or as the article observes:

The cruelty of delivering those animals, however, violates Islamic law which requires that animals for consumption must be treated with kindness and respect throughout their lives, be well-fed, healthy and free from disease or injury.

The shipping sector is notorious for its lack of regulation and poor practices, and when you look into the animal shipping business, it is no different.

40% of the 129 ships listed as being animal transporters are flying flags of convenience. Many of the ships used are old. A typical animal transporter ship is 38 years old, whereas a typical container ship is 13 years old. Many have been adapted, poorly, for example from ro-ro ferries, rather than being built specifically for the purpose. This means that there are compromises in the conversion process, and these compromises are known typically to be bad for animal welfare.

In practice, this may not make that much difference: the Al-Kuwait, which docked in Cape Town, is purpose-built. Its parent company, the Kuwait Livestock Transport & Trading Company, which owns Al Kuwait is one of the biggest animal carriers in the world:

(It) has been accused of providing substandard conditionsfor livestock – including overcrowding, poor ventilation and insufficient access to food and water – high mortality rates, mishandling of animals and lack of transparency.

More generally, the EU estimates that more than half of the vessels that ship animals are “high to very high” safety risk, and do not comply with EU animal welfare legislation.

It found that their interior fittings were unsuitable for live animals, resulting in them often injuring themselves, and many vessels were inadequately ventilated. “The ammonia levels on cattle transports are also so high they cause eye irritation and sometimes blindness.”

There’s a long list of cases in the article where cargoes have been rejected because thousands of the animals had died.

In fact, the EU is quite a good place to start if one wants to address this issue. EU countries are involved in this trade, and as the animal welfare organisation Four Paws has noted,

Since 2007, the EU Animal Welfare Transport Regulation (Regulation (EC) 1/2005) for the protection of animals during transport has been in force... Although the European Court of Justice has ruled in 2015 that EU animal welfare rules on animal transport apply beyond the EU borders and have to be adhered to until the final destination, there is evidence that this is not being applied in practice.

So member states could stop authorising such transports without much higher standards of proof of animal welfare. Ports can also impose conditions on ships coming in to load or unload. But the real question is why this trade exists at all.

Four Paws has proposed a set of regulations that would, basically, just ban it:

Ban live animal transports to third countries.

Ban animal transport by sea.

Ban long-distance transport with a duration of more than eight hours (four hours for poultry).

Ban transport of unweaned animals.

Animals must be slaughtered at the nearest suitable slaughterhouse.

No approvals of animal transport when temperatures are lower than 5°C or greater than 25°C.

Strengthening controls on live animal transport to ensure better enforcement.

More sanctions in case of infringements.

Transport of meat instead of live animals.

UPDATE: AI

I noticed a bit more over the weekend about AI and the idea of ‘model collapse’, which I mentioned in passing on Friday, at an article from last year in Axios. The article mentioned three versions of this, although they seem to be different metaphors for the same thing.

The first is “model collapse” itself, in which AIs are increasingly trained on the output of other AIs:

Feed a model enough of this "synthetic" data, and the quality of the AI's answers can rapidly deteriorate, as the systems lock in on the most probable word choices and discard the "tail" choices that keep their output interesting.

Second, what the researchers have named Model Autophagy Disorder, which has been done with an eye to the acronym, I’d say: the metaphor here is mad cow disease:

Our primary conclusion across all scenarios is that without enough fresh real data in each generation of an autophagous loop, future generative models are doomed to have their quality (precision) or diversity (recall) progressively decrease.

The whole article, linked above, is outside of a paywall.

The third metaphor is the famously inbred Habsburgs. ‘Habsburg AI’ describes

“A system that is so heavily trained on the outputs of other generative AIs that it becomes an inbred mutant, likely with exaggerated, grotesque features."

Secondly, the impact of AI use on energy requirements has been noted by some writers but largely ignored in the discourse about AI.

In a piece that’s mostly behind the Medium paywall, Will Lockett picks up on this. Or rather, he picks up on the fact that Sam Altman of OpenAI mentioned this in remarks he made at the World Economic Forum:

During one of the many meetings, he warned that the next wave of AI systems will consume vastly more power than expected, and our current energy systems will struggle to cope. He even went as far as to say, “There’s no way to get there (next-gen AI) without a breakthrough.” This marks a profound turning point in the AI hype train, as until now, their energy usage and associated carbon emissions have been the elephant in the room.

'Breakthrough’, here, seems to mean access to vast supplies of cheap (and likely) clean energy. Another one for the nuclear fusion researchers to work on, I guess.

j2t#546

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.