2 February 2022. Futures | Advertising

Escaping the endless present with ‘tropical futures’. The climate challenge facing advertising.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Escaping the endless present with ‘tropical futures’

Wired magazine is running a series on futures at the moment, and one piece that caught my eye was an article on ‘tropical futures’ by the design futurist Alex Quicho. (Thanks to Bryan Alexander for the link).

There’s a long preamble explaining why conventional business futures is no longer fit for purpose, which I don’t disagree with, but if you’re interested in the idea of tropical futures I recommend you skip past it. Here’s a taste of that critique anyway:

So-called realism has trapped us in an interminable present, where even the most daring innovations fail to envision a better and more equitable world—and in fact depend on the failure of our imagination for their successes, if you consider how Amazon’s delivery-on-demand has merely set a precedent for further deteriorating working conditions; or that Elon Musk’s Hyperloop only makes sense in a future without public access to transit; or how Meta can only envision alternate-dimensionality as an office-cum-mall that hasn’t even corrected for landlords.

But as she implies, most of the strategies that have been adopted by futurists to try to get past this interminable present end up getting captured, or recuperated. Hence the attraction of ‘tropical futures’, named for the art collective the Tropical Futures Institute.

(T)he “institute” is in fact a decentralized, roaming think tank that produces exhibitions, provocations, talks, artworks, trend reports, music compilations, and some very good T-shirts. Their Instagram has been a primary mode of outreach, and it catalogs a variety of research materials, from cultural critic Rahel Aima’s proposition of “warm water solidarity” to images of man-made islands and floating reef hotels.

—

(Images from the Tropical Futures Institute’s Instagram)

What tropical futures consists of isn’t really defined, but there is a direction of travel:

In a statement for a symposium they hosted this year, they mentioned: “It is good to talk about the tropics since we’re all from the tropics. Rather than wait for some cultural institution from the ‘center’ to harvest from the periphery once again (or) be a footnote in someone else’s historical narrative.”

In the absence of something more concrete, Quicho proposes a couple of ideas that seem to align with the Institute’s thinking. The first is about indigenous thinking, with more than a nod towards Stephanie Comilang’s 2016 documentary film Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso:

Indigenous land relations—which have long taken a reciprocal attitude to land use—are useful to guide development, or so-called “terraforming,” onto a firmly ethical and ecological track. Animism provides a philosophical framework for understanding how to live alongside, rather than in command of, living and non-living entities—even artificial superintelligence. And equitable forms of community governance, as Comilang touches on in her film, can inspire models for collective organizing.

The second principle is deceleration—a slower future, not a faster one. I’ve written before about how many of our systems are slowing down, not speeding up. But as Quicho points out, ever since Alvin Toffler published Future Shock, the story has been about acceleration. The task of imagining alternatives has fallen to artists:

(A)rtists such as Ronyel Compra are turning to ad hoc tropical technologies to envision a slower future. His project The Habak: Majority World Survivalism documents and tests tried-and-true practicalities that blend ecological and synthetic materials, moving the vision of tropical futures away from ultra-sleek air-conditioned developments and oil rigs perched on top of coral reefs, and into the provinces of semi-passive farming, spearfishing, and seed banking... The Habak has since grown into a comprehensive meditation on ecology, indigeneity, and survival, envisioning a tropical future that depends on the floating connectedness, and community scale, of the archipelago.

The third principle she proposes is the idea of ‘a regenerative future’, which she defines as a “move from an extractive society to one that humanely participates in the complex system called Earth.” Again, her example of this comes from the Global South:

In a recent article about food equity, the collective A Growing Culture argues as much, pointing to the major city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, where hunger was “virtually eliminated” by “political will, the strengthening of governance systems, declaring food as a right of citizenship, and correcting for hunger as a market failure.”

These are political solutions, rather than technology solutions. (And without knowing about the Belo Horizonte work, we came to similar conclusions in a report last year on the future of food environments in London.) They involve forms of innovation, but not the types of innovation we normally talk about. As she observes:

They underline the necessity of redefining “innovation” to discard old-school ideas of market viability, and to focus, instead, on total system transformation that does not see “political will” as a skippable step.

2: The climate challenge facing advertising

One of the perks of writing daily is that you can tear up the schedule when someone tells you something interesting. In yesterday’s post on marketing and climate change, I mentioned ‘The Purpose Disruptors’, who had prompted Leo Rayman’s post.

And a little later on I got an email from the co-founder of Purpose Disruptors, Jonathan Wise, pointing me to their report on the climate change impact of advertising in the UK.

The report proposes a metric—‘Advertised Emissions’—which enables the advertising industry to measure its emissions impact:

The adoption of Advertised Emissions would enable the industry to move beyond measuring just its operational footprint to measuring the emissions connected to its core function in society. It can then begin to purposefully direct its unique skills of creativity, imagination, planning, analytics and activation towards tackling our climate emergency.

To calculate the impact, the group did new research on the increase in emissions as a result of the advertising industry—not just those it generates through day-to-day operations, but the emissions generated by the effects of advertising, such as sales uplift:

This uses known and widely accepted sources on advertising spend, emissions, and supply chains. Additionally it deploys the new advertising research community (ARC) database which brings together – for the first time – results that show advertising’s return of investment for hundreds of real-life UK advertising campaigns evaluated using econometrics.

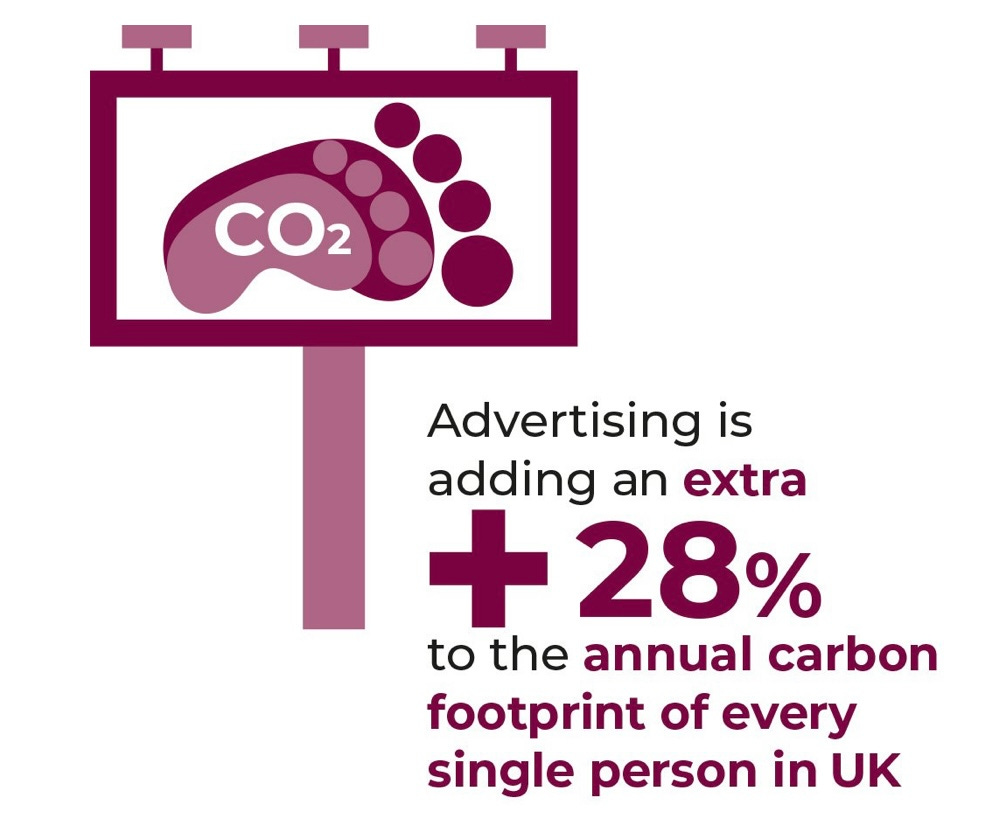

The headline figure that this generates is that the advertising industry in the UK is responsible for 28% of UK emissions, which is a huge figure.

(Source: Purpose Disruptors)

Now, I’m willing to believe that this is an over-estimate—there are studies from outside the industry that say that advertising has less impact on purchase behaviour than industry analysis says it does. But, you can’t have both ways. If you’re going to claim for the purposes of measuring impact that your work is this effective, then you need to take responsibility for the consequences of that as well.

I’m just summarising the executive summary here, but the group proposes a framework to help the advertising sector manage its way towards having a lower impact. This is a straightforward traffic light system, which splits brands into Red, Amber and Green.

Red brands are “high carbon brands and industries with little opportunity to re-engineer demand towards low carbon alternatives.”

Amber brands are “established brands and industries that can accelerate the adoption of lowercarbon attitudes and behaviours.

And Green brands are “new and emerging brands and industries whose business model is geared to serving a 1.5°C world.”

And this framework leads to some simple responses: Reduce spend on Red, increase spend on Green, and transition spend on Amber away from higher carbon products and services towards lower carbon parts of their business portfolios.

I like the simplicity of this, because it seems increasingly clear that the only way that established commercial businesses change their behaviour towards low-carbon alternatives is either when regulation steps in or when younger members of staff start protesting about the climate impact of their work, formally or informally. And this makes it pretty easy to propose alternatives.

The report also proposes a set of initiatives to help the industry confront this issue. The ones that caught my eye were:

The integration of Advertised Emissions into advertiser and agency emissions reporting and therefore part of those organisations credible, science-aligned net zero plans.

An independent scientific expert body (such as the Science Based Target Initiative) to produce common rules for accounting for Advertised Emissions and for setting science-aligned goals and targets for their reduction...

Willing members of the ecosystem to co-create a tool that all relevant organisations in the ecosystem can use to measure and reduce their Advertised Emissions.

We’re at an interesting point in the climate discussion—as Leo Rayman effectively argued in his post—where the notion is gaining ground that organisations need to take responsibility for all of the emissions their activities create, right along their sales chain. Rather than just those they create directly in their own operations. Measurement helps, of course, but culture and values are quicker.

So I suspect that the traffic light framework might have more impact than the measurement process—even if the measurements are necessary to budge the industry, or to shame it. I haven’t seen a story yet about an agency firing a high-emissions client, but I don’t follow the sector closely. And it would probably be an effective way of attracting talent.

Updates:

In case you didn’t get enough of Davos in Just Two Things last week, the launch memo on Izabella Kaminska’s new financial media service comes with a song—regretting, perhaps tongue in cheek, the days when Davos was in person and a lot more glitzy than it is now. Those were the days.

j2t#255

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.