1 February 2022. Marketing | Wordle

Beyond marketing to reducing emissions and consumption. The secret of Wordle is social graphic design.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: Beyond marketing to reducing emissions and consumption. Maybe.

Marketing is one of the dark arts of capitalism. You don’t need to be particularly critical of it to think that it is about creating wants rather than needs. Other definitions are available. But the briefest of dips into its history links it back to the way in which Alfred Sloane invented the 20th century corporation at General Motors in the 1920s and 1930s, creating a series of models that were then targeted at different income groups.

There’s a reason why—in the last decade or so, when corporate growth has been a struggle—marketing agencies have re-positioned themselves as ‘growth agencies’.

Which is why it’s interesting to read a post by Leo Rayman suggesting that marketing, and marketers, need to do something different. (Thanks to Matt Woodhams for the link).

This is his starting point:

At my core I’m a marketer and despite no shortage of goodwill, as well as the brave efforts of people like the Purpose Disruptors, I’m disappointed by the small ambition and lack of heavyweight impact from the marketing community. Sure there’s a lot of ‘green communications’ type work going on. But while well-intentioned or perhaps naïve, too many of these first generation initiatives have actually helped draw a ‘green veil' across the face of otherwise unchanged businesses.

And in effect, the short answer to this challenge is, Rayman suggests, that marketers should stop focussing on their clients’ businesses and focus on their customers’ instead. They should, in short, start creating narratives about changing behaviour rather than moments of consumption. In turn, the reason for this is that—by some way—most of the emissions don’t happen inside a businesses’ production and supply chain. He uses Macdonald’s as an example:

According to their CDC filing, emissions from their offices and restaurants (scope 1) fell from 1.5m to 0.6m tonnes of CO2 in 2019. Bravo! In the US and UK they have recently launched a net zero restaurant. But when you include Scope 3, McDonald’s total greenhouse gas emissions for 2019 were greater than those of either Portugal or Hungary at 54m tonnes, an increase of 7% in 4 years. That’s driven by their supply chain and the 7m cattle slaughtered each year. So McDonald’s real ambition for change has to include partnering with customers, creating a universal aspiration for plant-based burgers. The current McPlant ad campaign looks like a good step in that direction.

—

(Drive through McDonalds. Photo by David Lally, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Well, maybe in terms of emissions, but maybe not in terms of public health. That depends on how the plant-based burgers are put together. All the same, there are quite a lot more things that McDonald’s needs to be thinking about when it comes to their impact as a business. For example:

What if they helped customers not collect burgers at the drive-thru in their diesel-powered SUVs?

What if they found a way to reduce how much of over-ordered, uneaten food gets thrown in the trash?

How might they encourage replication of the McDonald’s experience at home with leftover mayo and small spice sachets?

How might they persuade die-hard meat fans to accept lab-cultivated beef?

How might they increase average order value whilst reducing the frequency of meat-based purchases?

There are reasons why businesses don’t do this. For one thing it’s hard to do; for another, it’s difficult to measure. It’s also difficult to work out whose responsibility it is. There’s a worldview problem as well. The production and consumption culture that defines most 20th century businesses means that businesses only tend to take responsibility for the effects of what they produce when law or regulation requires them to. Rayman’s a bit impatient with all of this:

(O)ne thing’s for sure, when we come to explain to our kids how we destroyed the planet, saying we couldn’t work out precisely who was responsible won’t cut it....

Here is his checklist of what marketing needs to do to change. I like the idea of the ‘minimum sustainable product’, which is a neat inversion of the tech industry’s obsession with the ‘minimum viable product’:

The next generation of marketers working on sustainability are moving beyond doomist thinking (yes, we’re in very, very deep trouble, now what are you going to do about it?) to an obsession with delivering genuine change.

Less shaping the narrative, more shaping behaviour.

Less ‘sustainability theatre’ workshops, more testing MSP (Minimal Sustainable Product).

Less internal focus and a lot more customer centricity.

Less risk management, more business model innovation.

Less reporting that reassures investors, more accurate measurement and responsibility for carbon being emitted.

Of course, the problem with a lot of this is that meaningfully reducing emissions involves reducing consumption, especially by the most affluent. And even with business model innovation, it’s hard to maintain growth or increase profitability while reducing consumption. Marketers don’t get paid for doing that. The incentive systems are all wrong.

2: The secret of Wordle is social graphic design

Everyone on the planet with access to a keyboard has expressed an opinion on the online word game Wordle by now. They like the fact that it was built by the developer as a present for his partner, who likes word games. They like the fact that he has gifted it to the internet rather than trying to monetise it. They like it that it’s designed so you can only play one game a day, rather than encouraging addiction. In short, they like it that it seems to be a throwback to the innocent gift economy of the web from about 1998.

I’m not going to repeat any of that here.

Instead, I’m going to point to a twitter thread on Wordle by a ‘philosopher of games’, C Thi Nguyen.

The first experience a lot of people have of Wordle is: "wait, you just guess? But you quickly figure out you can construct your guesses to search the space of letter-possibility, and you probably want to do that thinking about letter-frequency. So the early experience is one of agency expansion. Like, you thought you had almost no agency, but you have way more than you thought.

He compares it to limit poker, where, similarly, you realise as you think about the game that you have much more scope than you imagined.

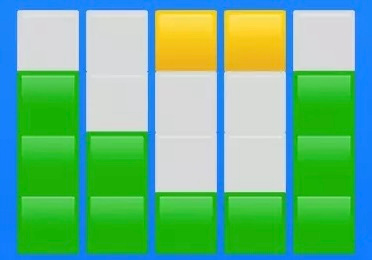

But he reckons that the cleverest part of Wordle is the graphic that shows how each game has gone. Again, it takes a little time to learn how to read it:

each little posted box is a neat synopsis of somebody's else's arc of action, failure, choice, and success. ... That's the really special thing about Wordle, I think. I don't know any other game that has nearly as graphically neat a synopsis, where you can just see the whole arc of another's attempt so quickly.

And this box combines with another design decision that makes Wordle distinctive: there’s only one word a day, and everyone who plays it on that day—anywhere on the planet—gets the same word. The result?

(W)e can share a struggle. And you can quickly grasp the shape of each others' dramatic arc that day... Wordle is a triumph of social graphic design.

——————————-

j2t#254

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.