24 January 2021. Citizens | Risks

From subjects or consumers to citizens. Global risks as seen from Davos.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish daily, five days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. Recent editions are archived and searchable on Wordpress.

1: From subjects or consumers to citizens

Jon Alexander was on the How to Fix Democracy podcast, hosted by Andrew Keen, talking about the ideas in his forthcoming book, Citizens (40 minutes). Alexander is the co-founder of the British-based New Citizenship Project.

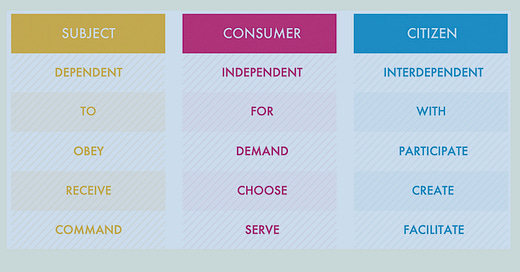

He has a straightforward underlying model, which is worth sharing. We have been positioned in one of three ways in different places and at different historical moments: as subjects, citizens, or consumers.

(Source: Jon Alexander)

If we are going to solve our pressing collective problems we need to be able to act as citizens.

Of these three, consumers is the most recent. Alexander traces this back to Edward Bernays in the 1930s, who took ideas about psychology – especially social psychology – and translated them into ways to sell things. (Adam Curtis has a whole series about the world Bernays made).

Advertising already existed before Bernays came along—in the modern sense, this goes back to the mass circulation magazines and newspapers of the late 19th century. But Bernays translated it into a mechanism to shape and manage the way the public thought.

The effect, says Alexander, has been to make people think that we have an individualistic relationship with the world, mediated through our purchasing decisions.

But we also have centuries behind us of being positioned as subjects in which our “social betters” tell us what to do or think. To some extent this set of relationships has also been reinvented in different parts of the world, typically in authoritarian regimes such as contemporary China.

Andrew Keen, who is a good interviewer who believes in stretching his guests, pushed Alexander quite hard on the relationship between consumerism and capitalism, without getting very far.

As a listener, this was disappointing, since we also know that the relationship between consumerism and climate change and bio-degradation is fairly complete. The claims made by some about "decoupling" are largely unproven.

It might be relevant that Alexander started his working life in advertising. One of the prompts for his sharp change of direction was thinking about the social effects of living in a world where we see 3,000 commercial messages a day.

Equally, consumerism in its modern form doesn’t really take shape without the underlying dynamics of capitalist business that demand growth to pay returns to shareholders and owners.

All the same, it’s worth talking about what he sees as sources of change in the present moment.

He’s a fan of the deliberative assemblies that laid the ground for Ireland’s referendum on abortion. Several years later the Irish state does better on trust indices, and a higher proportion of its citizens are vaccinated.

At a company level, he is a fan of Brewdog’s version of shareholder owners – while acknowledging some of the company’s recent problems. He talked about McKinsey’s internal letter from staff asking the company not to engage with fossil fuel businesses.

These all come under the general heading of what he calls “acupuncture moments." These didn’t seem well defined on the podcast, but sounded like moments that prick the way that business as usual works. I guess we can extend the metaphor to suggest that these pricks also improve health.

It’s also pretty clear that he thinks that organisations, including commercial ones, can be the source of these acupuncture moments.

I’ve got some sympathy with the idea that we need to be citizens if we are going to respond effectively to climate change or to the Sixth Great Extinction, or to the excesses of wealth inequality that currently skew – or screw – our current political systems and our investment decisions.

I’ve also got some sympathy with the idea of starting change where you are with "acupuncture moments." Hope is an important part of change even if such moments might not scale. But commercial organisations, and come to that non-commercial ones in capitalist environments, make certain types of decisions because of the way they are incentivised.

Even if you don’t want to talk about capitalism, you need to talk about changing the rules and incentives that shape behaviours within it. Otherwise the music keeps playing and everybody feels the need to keep on dancing.

2: Global risks as seen from the C-suite

One of the problems of Davos, even when it’s not held in person, is that it’s used by organisations to put out their regular reports that by now represent a longitudinal body of research.

One of these is the World Economic Forum itself, which pumps out its so called “risks” report. Edelman also updates its more useful annual Trust Barometer, and Oxfam reminds us of the way the world’s wealth is divided. I’m going to pick these three up over the course of the week.

The grandly titled World Economic Forum “Global Risks Report” is now in its 17th year. Of course, it isn’t really what it claims to be—it samples its constituency of the global C-suite and their retinues (“the global risks perception survey”), and writes down what they say. So the perception of risks here has proved over the years to be as short-termist as their business management. It’s rarely aligned with much consideration of planetary boundaries, for example.

Nonetheless: since they are influential, we need to know what they think. This is as close as we get to this year’s official view of the future. And I’m perhaps being slightly harsh about the quality of the work: there is commentary and data around the opinion.

And just to be clear: I’ve read the executive summary and skimmed the rest.

So without further ado—here’s their top ten perceived risks in 2022.

(World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report, 2022)

Five of these, including the top three, are environmental issues, as they have been since 2019. Two of the three social issues are, broadly, economic. These last two are reflected in the data points at the start of the ‘worlds apart’ chapter—that only 6% of those in the 52 poorest nations have been fully vaccinated, and a projection that another 51 million people worldwide will revert to extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic. Every time I see that vaccination percentage I’m reminded what a huge global public policy failure it represents.

The chapters work through seven issues—‘worlds apart’, on social cohesion or its lack, ‘disorderly climate transition’, ‘digital dependencies and cyber vulnerabilities’, ‘barriers to migration’, ‘crowding and competition in space’, and ‘refreshing resilience’. Obviously the space chapter jumps out a bit there as maybe not being as pressing as the other issues, but seems to have been good for picking up headlines.

This is the summary on the post-pandemic prospects:

The economic fallout from the pandemic is compounding with labour market imbalances, protectionism, and widening digital, education and skills gaps that risk splitting the world into divergent trajectories. In some countries, rapid vaccine rollout, successful digital transformations and new growth opportunities could mean a return to pre-pandemic trends in the short term and the possibility of a more resilient outlook over a longer horizon. Yet many other countries will be held back by low rates of vaccination, continued acute stress on health systems, digital divides and stagnant job markets. These divergences will complicate the international collaboration needed to address the worsening impacts of climate change, manage migration f lows and combat dangerous cyber-risks.

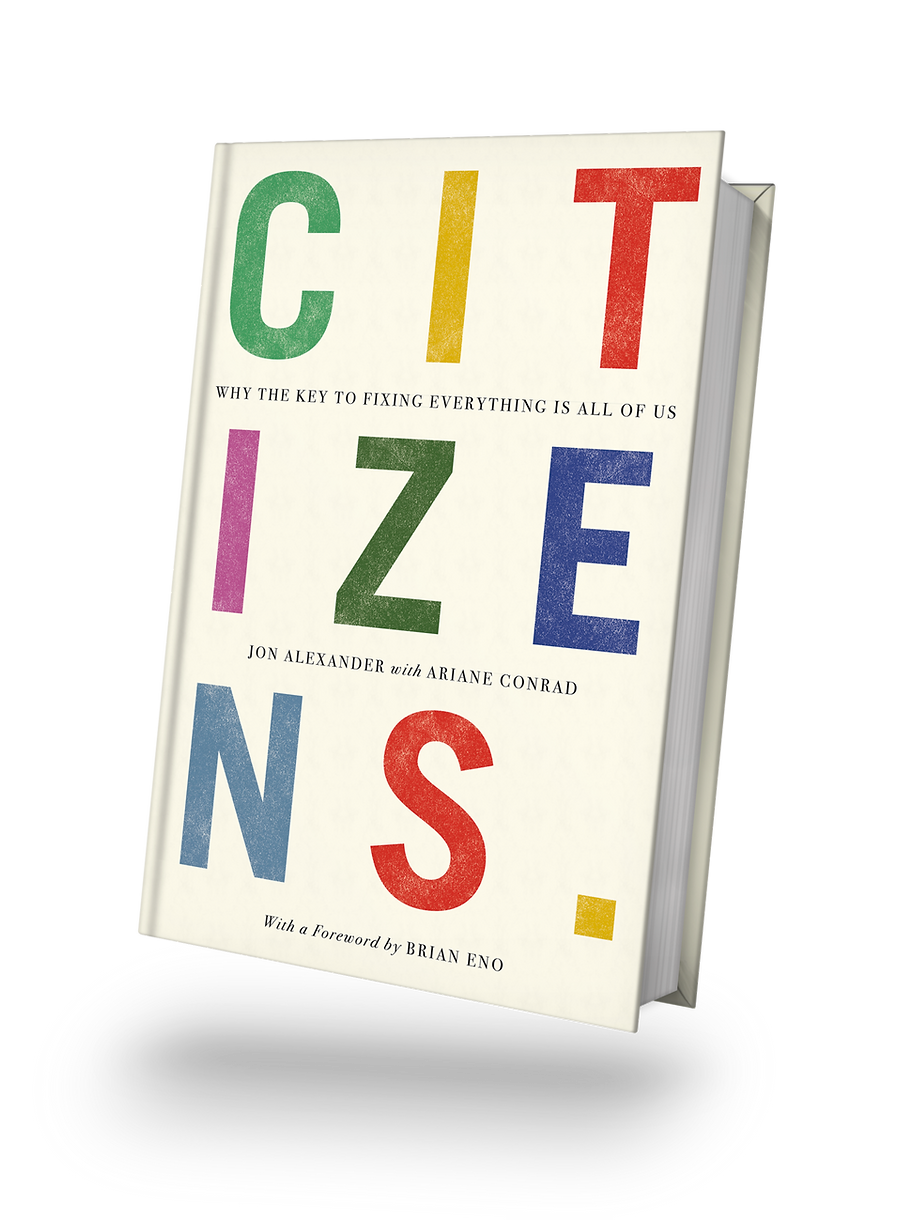

One data point that is worth noting is that the WEF’s respondents are pretty gloomy about the prospects. Five out of six describe themselves as ‘worried’ or ‘concerned’—less than one in twenty-five tick the top box (‘optimistic’) on this slightly eccentric four point scale.

(World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report, 2022)

Normally business leaders are more bullish than this, but maybe the anonymity of the survey allowed them to be more honest with themselves.

Obviously it’s a good thing that business leaders have noticed that there are risks associated with climate change. But the specific language in the report is also noticeable—about the risks of disorderly climate transition:

Given the complexities of technological, economic and societal change at this scale, and the insufficient nature of current commitments, it is likely that any transition that achieves the net zero goal by 2050 will be disorderly... Countries continuing down the path of reliance on carbon-intensive sectors risk losing competitive advantage... Yet shifting away from carbon-intense industries, which currently employ millions of workers, will trigger economic volatility, deepen unemployment and increase societal and geopolitical tensions.

Given the scale of the climate emergency, the increasingly short-run need for action, and the number of environmental risks noticed by their respondents, you’d have wanted them to get off the fence.

Of the rest, it’s also worth noticing the language about migrants, where they see labour market protections and tightening migration rules as having adverse affects on global cohesion and economic opportunity:

In 2020, there were over 34 million people displaced abroad globally from conflict alone—a historical high. However, in many countries, the lingering effects of the pandemic, increased economic protectionism and new labour market dynamics are resulting in higher barriers to entry for migrants who might seek opportunity or refuge. These higher barriers to migration, and their spillover effect on remittances—a critical lifeline for some developing countries—risk precluding a potential pathway to restoring livelihoods, maintaining political stability and closing income and labour gaps.

Of course, the business leaders of some of the biggest corporations in the world could do something about many of these risks if they wanted to. But that’s not what Davos is for. As I’ve written about before: it’s to make them feel better about their failure to do almost anything meaningful or consequential about anything.

j2t#249

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.