18 March 2025. Geopolitics | Systems

To Russia with love: American realignment // What stories do for systems [#633]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish a couple of times a week. Some links may also appear [on my blog] from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

My professional workload is still heavy, so Just Two Things will be a little intermittent for another couple of weeks or so.

1: To Russia with love

What to make of the rapprochement between the new US Administration and Russia? It’s easy to imagine the easy explanations: that Putin is the kind of bareback riding autocrat that Trump, in his dreams, would long to be. Or, as has been alleged from time to time, perhaps unreliably, that Trump is some kind of Russian asset.

What I’m going to suggest in this post is that to understand what’s going on you need to go deeper.

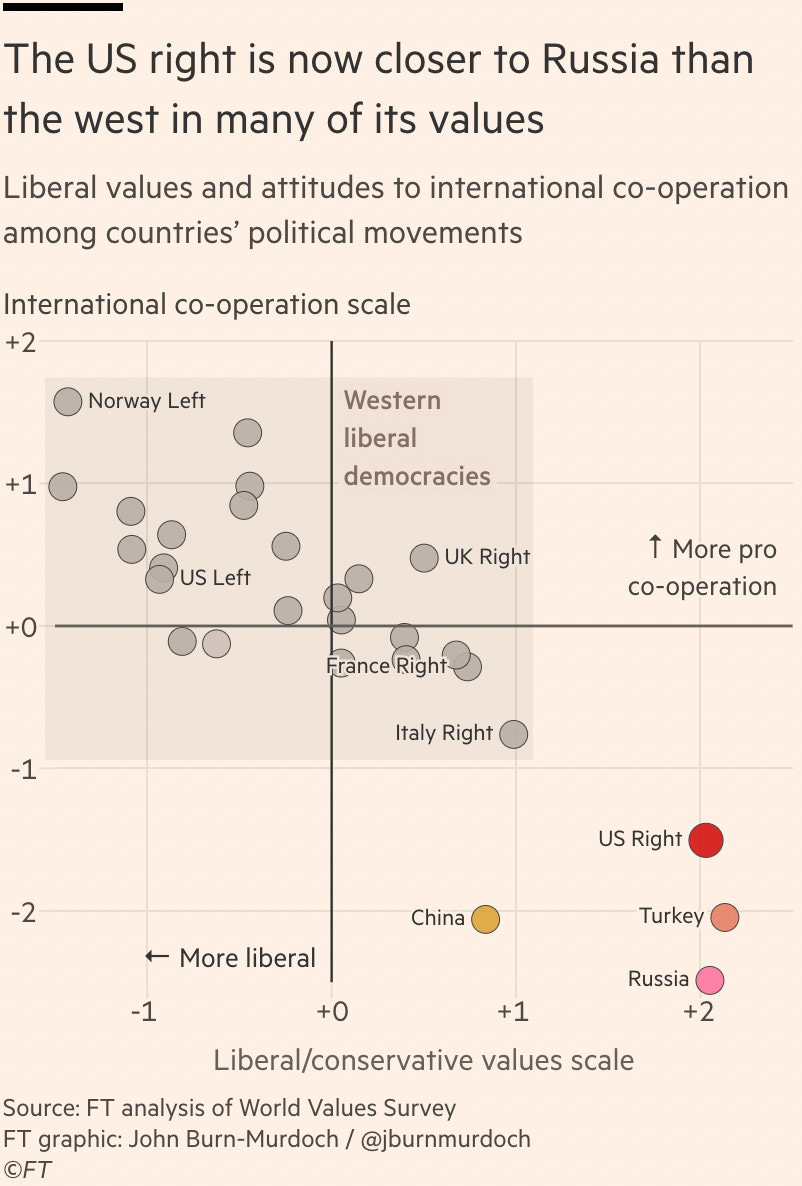

All the same, some of this might just be playing to the base. The first observation has to be about how much of an outlier MAGA supporters are globally. We have data on this, thanks to some analysis of the World Values Survey by John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times.1

(Source: John Burn-Murdoch, Financial Times, via Bluesky)

The data used here are a couple of years old and Burn-Murdoch thinks that the MAGA base has become more conservative and less in favour of co-operation since, given the striking historic trends.

(Source: John Burn-Murdoch, Financial Times, via Bluesky)

While thinking about this question, I found an interesting article in the Serbian magazine Pecanik, written by Dmitri Pozhidaev earlier this month. Its starting position is:

Far from an impulsive departure from tradition, this recalibration reflects a broader evolution in American strategic thinking. The US is moving away from the territorialist logic of power, which relies on costly military interventions and direct control, toward a more economically driven and cost-effective strategy of influence.

Although most of the article was written before Zelenskyy’s meeting at the White House with Trump and Vance. But Pozhidaev suggests that the meeting

ultimately follows a consistent logic: prioritizing strategic advantage over ideological commitments.

The idea of “territorialist logic” is drawn from Marxist ideas about geopolitics, notably the work of Giovanni Arrighi and David Harvey. It requires

substantial investment in military bases, overseas troop deployments, and the upkeep of alliances like NATO. However, this approach has become increasingly costly and, in many cases, strategically inefficient.

Iraq and Afghanistan are cases in point, but even in Europe the costs have been going up faster than the strategic benefits.

In David Harvey’s discussion in his 2003 book The New Imperialism, these new forms of influence involve

more flexible forms of economic and geopolitical control, where coercion, financial leverage, and market mechanisms replace the need for physical occupation. The U.S. is increasingly relying on cost-effective instruments of influence, such as sanctions, trade policies, and financial restrictions, rather than direct military engagement.

In this, therefore, the Trump Administration is really only following the lead of the Biden Administration. The implication is that Great Power competition is now more about economic and technological supremacy than military influence and control.

Pozhidaev summarises the rationale for a rapprochement now, and since it’s a long article and there’s more to say, I’m just going to share the headlines on there:

Access to strategic resources.

The costs of sanctions and economic decoupling.

Sanction enforcement also carries costs.

Repositioning Europe as a competitor rather than an asset.

There’s a fifth factor here, of course, and that is competition with China. Over the last three years Russia and China have deepened their partnership, in energy trade, military cooperation, and financial transactions. Sanctions have accelerated this process.

For the US, this growing alignment between Russia and China represents a major long-term threat. Washington’s goal, therefore, is to prevent a full-fledged Russia-China axis by creating incentives for Russia to maintain a degree of independence from Beijing.

In the Cold War, the US similarly exploited tensions between China and the USSR to separate Beijing and Moscow. Trump stated this as an objective on the campaign trail:

“The one thing you never want is Russia and China uniting. I’m going to have to un-unite them.”

And one of the calculations that sits behind this for American policymakers is that Russia is seen as a problem but Russia is seen as a threat.

There’s some theory that sits behind this overall view as to how America should approach this. This is known as the “offshore balancing” framework, developed by John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt. This

identified three key regions of US strategic interest—Europe, the Persian Gulf, and the Asia-Pacific—where direct military entanglements are undesirable, but preventing the rise of new hegemonic powers remains a priority.

On this reading, Russia acts as a balance to China in the East, because of its long land border, while Europe acts as a balance to Russia in the West. Hence the pressure from the United States on Europe to spend more on their own defence.

But geopolitical logic notwithstanding, there are risks in rapprochement with Russia. Again Pozhidaev spells them out at a bit of length, and I’m just going to list them out here:

deep-rooted distrust between the United States and Russia; the continuing war in the Ukraine; internal political opposition within the US; the risk of strategic overreach by the US, in which it makes concessions to Russia but doesn’t get strategic benefits; and risks of nuclear escalation.

All the same, this is a deep shift, not just about Trump’s authoritarianism. As Pozhidaev argues:

The shifting U.S. stance toward Russia is not just about diplomatic maneuvering but a response to the ongoing crisis of capitalism, where the current model of accumulation in the U.S. faces significant structural challenges. Mending bridges with Russia is not merely about geopolitical realignments—it is a strategy to expand the breathing space for U.S. capitalism itself.

There’s some other theory that sits behind all of this. The American political theorist Gary Gerstle has described in a couple of books (one co-edited with Steven Fraser) the idea of “political orders”. In short, he argues that American politics has been by two 40-year cycles in which a dominant set of ideas set the frame: first, the New Deal, from circa 1940 to circa 1980, and then neoliberalism, from circa 1980 to the mid 2010s.

A review by Patrick Andelic of the second of these books summarises the idea:

By “political order,” Gerstle means “a constellation of ideologies, policies, and constituencies that shape American politics in ways that endure beyond the two-, four-, and six-year election cycles.” The “neoliberal” order was the second to dominate US politics in the twentieth century.

You can see a similar pattern in British politics too, perhaps going back even further, to the cycle started by the Liberal government in 1906.

And as Andelic notes:

Gerstle writes at a moment when it seems likely, but not certain, that the political order he is studying has expired.

We could discuss why these are 40-year cycles, and you can see reasons that this might happen, based around the length of a working life, in which one group of managers or leaders fix a set of problems, and the next generation has to deal with the contradictions created by those earlier fixes.

In the case of the New Deal, it probably created too much equality for capital to be comfortable; in the case of neoliberalism, it created too much inequality for everyone else to be comfortable, as Gerstle suggests in an interview with the IMF.

He has a sketch of what the next “political order” might look like in that interview:

Governments now ask, What goods and services are essential for national security? What resources must every nation have for ensuring that the core needs of its people are met?... Once you enter that frame of mind, you’re not in a neoliberal world anymore, because now you’re privileging national security over market freedom.

And, as Gerstle says, almost every government in the world is thinking in this way about politics, and geopolitics. Neoliberalism was able to assume a peaceful world and open, if rigged, markets. We’re not in that world anymore.

2: What stories do for systems

Since he left academe to become a futures practitioner, the futurist and writer Paul Graham Raven has been running an interesting newsletter, Worldbuilding Agency, which includes commentary and extended interviews. (The usual disclosure: Paul is a friend and a sometimes colleague.)

The combination of futures and writing expertise leads to different perspectives on the work we do, and I was struck by a recent essay in the newsletter that explored that relationship between systems and stories in futures practice.

The starting point was a quote from a game designer, Alexis Kennedy:

“System and story: a good system is stuff that happens predictably and a good story is stuff that doesn’t happen predictably. I don’t mean that a good story needs to be a twist every scene, but if you know everything that will happen, it’s dull. Similarly a system will throw you surprises every so often, but it’s designed so that once you understand it, you can appreciate it and use it to predict the results of your actions.” [Emphasis in original]

Kennedy is writing about game design, and it’s fair to say that the story-and-surprise element is more important in game design than it is in futures stories. But it’s still an important observation: A futures narrative that has nothing in it that is surprising is less futures than forecasting.

Raven also notes that the system/story is more a continuum than a dichotomy: different types of work will end up at different points along the line, but even the most exploratory piece of speculative futures work will have some kind of system embedded in it if it is going to resonate with readers or listeners.

The essay continues by proposing a couple of working definitions:

Systems are predictable, despite their generation of surprises, because a well-considered system will have included within its parameters a certain scope for surprise... you’re trying to identify the rails you’d like to roll along.

Story, by contrast, is based on the unexpected and the obstructive: story is surprise, the discontinuity of the line, the avalanche or angry moose that might derail your journey.

Raven did a doctorate in infrastructure futures at Sheffield, working largely with engineers who know a lot about water, and he draws on that experience to pull out some of the distinctions here, starting with a quote from Kurt Vonnegut:2

Your character has to want something, even if it’s just a glass of water.

(Just a glass of water. PublicDomainPicture.net)

Of course, a glass of water is a good starting point if you’re working with a group of water experts. A systems approach would probably go like this:

You look at trends in, say, population growth, urban/rural migration, and per-capita water demand per day, and that gives you an idea of how much capacity you might need in a given location in the next twenty years or so—which in turn lets you decide how many new reservoirs or treatment plant or pumps or pipes you need to install.

And so on.

A story approach, on the other hand, is a way to look at the discontinuities in the system, the points at which the prevailing system might get disrupted:

Your Vonnegutean character will find that their glass of water is not so easy to acquire as they’d like. “Thirsty person gets glass of water” is not a story; hell, it’s not even an anecdote! But “thirsty person turns tap and nothing happens”—now that’s a story, or at least the start of one.

Once you get into why nothing has happened, that story could even become a or suite of stories. Drought? Sabotage? Crumbling infrastructure? Water pump turned off because of cholera risk? There are a lot of reasons why the tap might not be gushing water that disrupt that apparently predictable system of water provision.

And although I generally think that scenarios are over-rated in futures work, when I did some work with the English Environment Agency some fifteen years ago on the long term future of water, the trends-based demand-led scenario among the set turned out to involve building a lot of reservoir capacity—and probably not enough sites, or planning capacity, to actually find locations for all of them. And of course, that’s also a type of story here.

But back to Paul Raven’s essay, because he makes this same point in a slightly different way:

a story-based approach is not going to tell you how much capacity you need to build out; questions of quality and externality will not give you answers of quantity and internality. But it will, if done properly, show you the limits of the system/model approach—quite literally so, in fact. The story’s capacity (indeed, affinity) for surprises gives you a way to explore the breakdown of the border of the system.

I think Raven underplays one of the benefits of narrative in futures work, and this is connected to cognition. Every group that has a shared professional practice has, broadly speaking, shared mental models of how the world works. These change very slowly.

For example, it has taken several decades for transport practitioners to move from models of transport infrastructure provision based on “predict and provide” to “decide and provide”, and even now, you see zombie versions of the old model stalking political discourse despite it being completely discredited.

What story does here is allow us to ask “what if?” questions in a way that allows people to play with ideas about how the system might work differently, but without challenging people’s professional identity.

To add to this: The endless discussion in scenarios work about “plausibility” can often be deconstructed as a request by someone with an over-developed sense of professional or ideological identity not to have that identity disrupted by futures work. In the face of this, “what if?” stories that disrupt parts of a dominant view of how the systems is supposed to work may be the only way to explore these differences.

Raven puts it more elegantly than this in the essay:

Story is a stress-test of your systemic mapping; it’s a red-team exercise against not only your plan, but also the assumptions upon which that plan is built. Story is a warning—not that there’s no point in planning, but that you must plan for the plan’s failure, and never stop planning. [Emphasis in original]

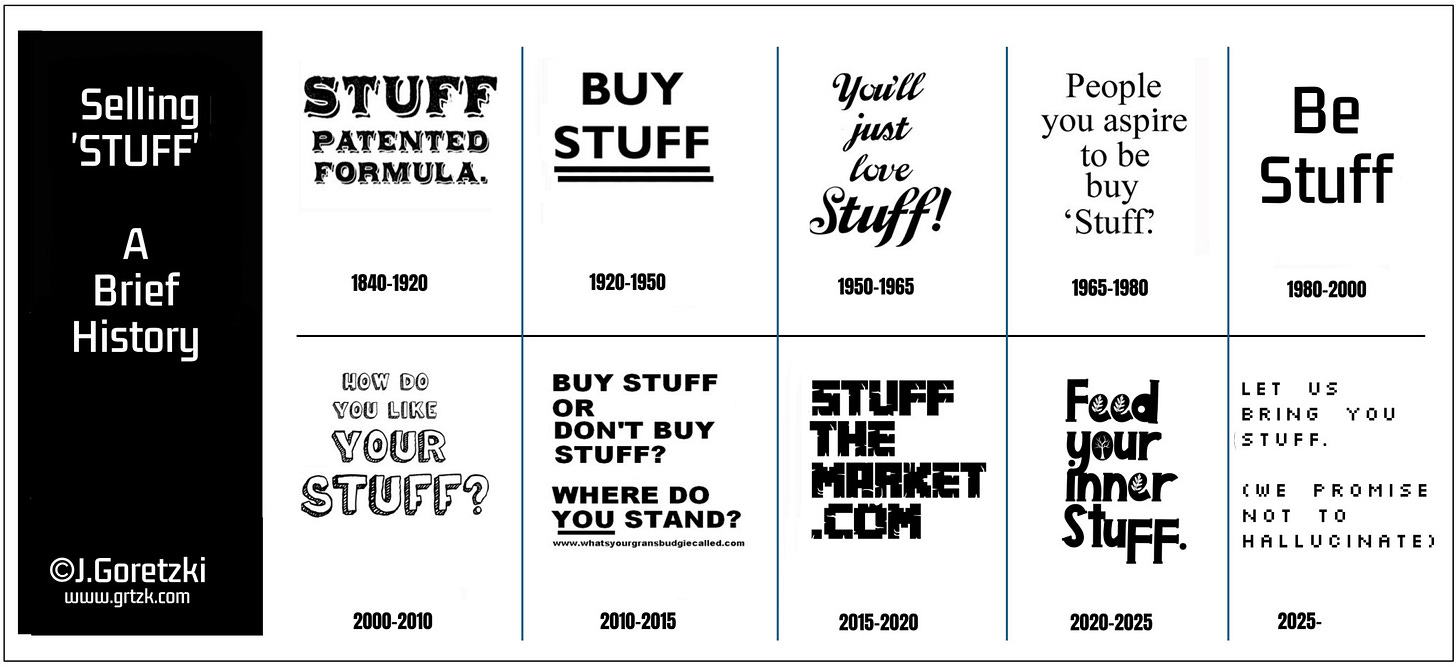

I.M. Jake Goretzki 1971-2025

I heard last week that my former colleague Jake Goretzki had died unexpectedly. Jake was a fine cultural and social researcher who spoke multiple languages, including German and Russian, and had a deep knowledge of the political and cultural landscape of Russia and of central Europe. (I recommend his piece on 10 Things A Russianist Would Tell You About Russia, maybe as a complement to my piece above.) He held strong views on politics—sometimes a little strongly for his own good—some of which I agreed with.

Those strong views extended to literature. He read widely and voraciously, and indeed, the last time we’d seen each other we’d ended up sending each other travel books that one of us had read and liked, but not the other. Jake had no time for the humblebragging that passes for discourse on LinkedIn, and instead used his account to talk about literature and politics, sometimes caustically.

His father had been born in 1941 in a part of Europe that happened to be in Germany at the time, and that meant that, after Brexit, he eventually got a German passport. He wrote about that on LinkedIn too, in a reflective piece called ‘From Wall’s to Bratwurst’: here’s an extended extract:

I’d grown up, you see, with ‘Europe Endless’ on cassette on a Sony WM-22, taking the train to Germany from Belgium in my school summer holidays and seeing ‘parks, hotels and palaces’ flying by without a border between any of them. The abrupt halt to that train acquired even deeper emotional force when the uncle and aunt in Germany I'd be visiting every summer died within two years of each other around the pandemic, leaving me feeling like I’d had a 40-point deduction and had dropped into the Combined Counties league, warming the bench for a pub team...

I was utterly sick, too, of the British conversation. I stopped listening to Radio 4 in the morning. I stopped reading English fiction, enraged that none of our writing ‘consciences of the nation’ were taking on this massive watershed as a subject, instead choosing to noodle about the nineteenth century or execute patronising caricatures of the Remain vs Leave dispute...

Germany is adidas to the UK’s mail order deck shoes from the back of the Radio Times. It's Kraftwerk versus Ed Sheeran. I love-hate-love London and I'll probably never leave, but while I’m stuck in a District line carriage outside Upton Park due to signal failures at Barking, in my heart I'm back on the Trans Europe Express.

Being a skilled social and cultural researcher meant that he ended up doing quite a lot of research for brands and marketers. I think this was uncomfortable for him. You have to eat, but he didn’t have much time for the people who paid the bills. Some of this found his way into his cartoons, an eclectic, sometimes angry, sometimes elliptic, sometimes surreal mix of styles and subjects. When I was editing reports for The Futures Company, I’d sometimes ask him if had a cartoon that I could use as an (ironic) illustration. So I’m going to remember him this way.

I know that some of my readers knew Jake. If you want to leave a memory, or make a donation in his memory, his remembrance page is here.

j2t#633

Since I was accused by the newspaper last year of breaching the FT’s copyright in using John Burn-Murdoch’s charts in the past, these charts have already been shared by Burn-Murdoch on his Bluesky feed, and I am re-sharing them here under the Fair Dealing provisions of the Copyright Act.

Kurt Vonnegut developed a typology of stories, which I wrote about in Just Two Things #520. It can be useful when you’re thinking about the trajectories of a set of scenario stories.