1 December 2023. Transport | Story

Making transport fairer and more siustainable. // Kurt Vonnegut’s story diagrams. [#520]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

And: have a good weekend!

1: Making transport fairer and more sustainable

I spoke this week at an event at London’s London Transport Museum on ‘Making transport fit for the future – what do we need the future to look like?’. The other speakers included Annette Smith, of Mott Macdonald, who is a colleague of mine on the DfT futures programme, Rikesh Shah of the Connected Places Catapult, and Krishna Desai of Cubic. The brief for the short presentation was to talk about how to increase the environmental, social, and economic equity of transport. Without some of the performative bits, this is a version of what I said, with a few extra notes in places. Some of this will be familiar to regular readers.

We are facing a triple crisis at the moment. The environmental crisis is moving from global warming to global boiling, as the UN Secretary General has pointed out. We have a massive crisis of wealth inequality. And in the UK, we have a productivity crisis whose second-order effects include a crisis of faith in the effectiveness of government and public agencies, and a crisis of trust. Maybe we have a fourth crisis as well—a crisis of time. Because the clock is ticking on all of these things.

Which is a long way of saying, perhaps, that there’s no point in tinkering around the edges.

As a futurist, one of the things I do is to look for seeds of change, or weak signals, as they’re sometimes called in the literature. A seed of change is a sign of someone seeing the world differently or doing something differently. A seed can be cultural, social, political, or behavioural.

What I am going to do in this talk is to review some of the seeds I’ve seen recently and talk about what I think they mean for a different view of what transport ought to do.

#1. Electrification

We need to electrify our transport fleets, but we really don’t want simply to swap our existing petrol-powered/ICE stock of vehicles for the same amount of electric vehicles. Fortunately the evidence suggests that the rise of e-bikes and e-scooters is replacing cars, at least at the edge, and having a significant effect on the demand for oil.

Point one: fewer cars

#2. Speed

Speed kills. I think we all know that. That’s why campaigns like ‘Twenty’s Plenty’ exist, to promote lower speeds, mostly in residential areas. And despite Downing Street’s rhetoric, these are generally popular with people who live in these areas, who are definitely the most important constituency here.

Of course, the Welsh government, which takes environmental and social sustainability seriously in its transport policy, is the leader in this area, in Britain and beyond.

Point two: Slower cars

(Source: Streets for Life)

#3. Size

The Tyre Extinguishers are a self-organised group of people who identify SUVs, unscrew the dustcaps, pop a lentil into the valve, screw the dustcap back on again, and leave a leaflet under the windscreen wiper. The tyre then deflates slowly.

The leaflet is about the environmental and social issues caused by big cars—on which there was another news report this week, this time saying that carbon emissions from cars would have fallen by 30% were it not for the way in which the motor manufacturers had created the SUV market to shore up their flagging profits.

Either way, the growth of the SUV market is one of the great policy disasters of our times. They need to be banned.

Point three: Smaller cars

#4. Excluded users

I’ve written about Lime bikes here before, but it turns out that they had a design bug that meant that it was possible to kickstart them in a way that circumvented the digital security, even if you didn’t get the use of the battery. Everyone’s bug is someone else’s feature, of course, and it didn’t take long for this design issue to be aired on TikTok, or for young people in London to take advantage of it.

Lime’s response was not pleasant, given that the design fault was on them, and the young people wouldn’t have been allowed to hire the bikes anyway because they were too young. There was much noise about “criminality” and “theft”. For my story here, I think this is about “desire lines”—they show what people would do if they could. Which tells a story about a group who are partly excluded from transport by price and the technology of finance (because credit card).

So, point four: better access

#5. Lower cost

I am of an age to have a freedom pass, which gives me free access to London’s public transport network 22 hours out of 24 it used to be more), and also to free use of local buses elsewhere. Every time I use it, I think that this is a form of Utopian demand, and wonder why other users don’t have the same access.

Free transport, certainly on buses, is increasingly commonplace—cities such as Tallinn have introduced it, as well as Luxembourg and Malta. In principal, it increases accessibility to labour market participation, and other forms of social and cultural participation, notably for the bottom quartile by income. In some cases it can reduce levels of underemployment. In other words, it is good for productivity.

Point five: free transport

(Source: Greenpeace)

Affordable, accessible transport

These five things point towards a transport system that delivers affordable, accessible transport to everyone. It surprises me that there isn’t more of a campaign around this, although I notice that Greenpeace has sort of been making the case for it. (And also here).

Because: there are significant areas of public policy where the design of the current system both pumps out external costs that everyone has to pay for, and acts as a drag on positive change that would have social, economic, and environmental benefits. Transport is one of these areas.

Another area where this is true, of course, is the food system. Just at a UK level, the health and environmental effects of the current system cost billions of pounds, and it acts as a significant drag on educational and social opportunity.

Unlike transport, there’s an active UK campaign for ‘the right to food’, involving cities, trades unions, and activists and community groups. That campaign has the ‘gateway drug’ of universal free school meals to build around. So I am wondering what the equivalent of universal school meals is in a campaign for affordable, accessible, transport.

2: Kurt Vonnegut’s story diagrams

A remark by Mahlet Zimeta in her Five Books interview on the best books on tech utopias and dystopias sent me back to Kurt Vonnegut’s theory that stories followed a small number of patterns that could be mapped. It’s an eclectic selection of books, by the way, taking in Nietzsche and Claudia Rankine via Svetlana Alexievich.

Vonnegut evolved his theory while he was an anthropology student at the University of Chicago in the 1940s:

“The fundamental idea,” he wrote, “is that stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper, and that the shape of a given society’s stories is at least as interesting as the shape of its pots or spearheads.”

He submitted a proposal to the department to explore this idea as a master’s thesis, but the idea was turned down. I think we can say now that he was probably just ahead of his time. His take:

His thesis was rejected, he said, “because it was so simple and looked like too much fun. One must not be too playful”.

But he didn’t give up on the idea, and returned to it over the years, entertainingly, when he gave talks on writing. There are short bits of these scattered across youtube. This one’s about five minutes. The voiceover at the start goes away quite quickly:

Vonnegut’s shape is built around two axes: Good (G) to Ill (I) on the left hand side, running downwards, and B to E, running left to right across the middle. B is for Beginning, and he’d joke, when presenting, about what the E stood for, but you can probably work that out for yourself.

He concluded that there were eight stories. (Christopher Booker reckoned that there were seven, although when you work through Vonnegut’s list of eight stories, there are only seven shapes). Like Booker, Vonnegut argued that every story ever told matches one of these shapes.

I’m not going to put all of the diagrams into this piece, but here’s a quick summary with a few of the diagrams. ‘Man in a Hole’ is a U-shape, starting towards the G-point on the Good/Ill axis, and plummeting down until they recover and regain their former position:

(A) character leading a perfectly bearable life finds misfortune, overcomes it, and is happier afterwards. “You see this story again and again,” Vonnegut said. “People love it, and it is not copyrighted.”

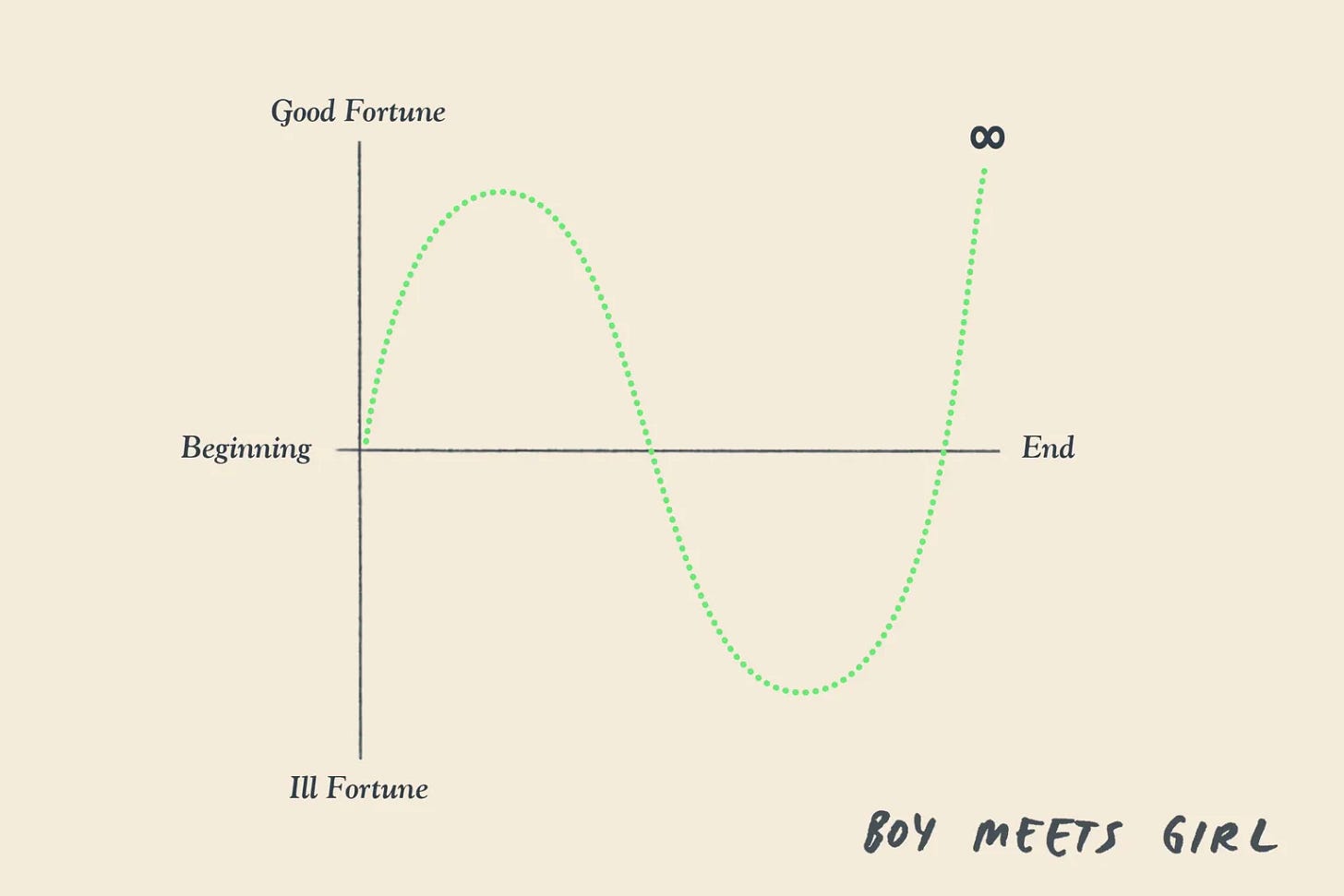

Boy Meets Girl has similarities. It starts in the middle, things get better, so it climbs towards G, something bad happens, so it heads down towards I, then things are sorted out and the line turns back up again. Every romcom ever. Almost.

(Source: The Story)

From Bad to Worse starts bad and gets worse. For example:

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

He also has a story shape called Which Way Up in which the state of the characters is so complex that it’s impossible to tell whether the things that happen are for good or ill. The line runs straight across, a bit below the Beginning to End line. For Vonnegut, this is Hamlet:

This, Vonnegut says, is just like real life: from a universal perspective, a thing that happens to you is neither good nor bad, but rather “just something that happened”. Whether Hamlet is better or worse off for seeking revenge isn’t really for us or Shakespeare to say. “We’re so seldom told the truth”, Vonnegut said, “but Hamlet tells us we don’t know enough about life to know what the good news is and the bad news is.”

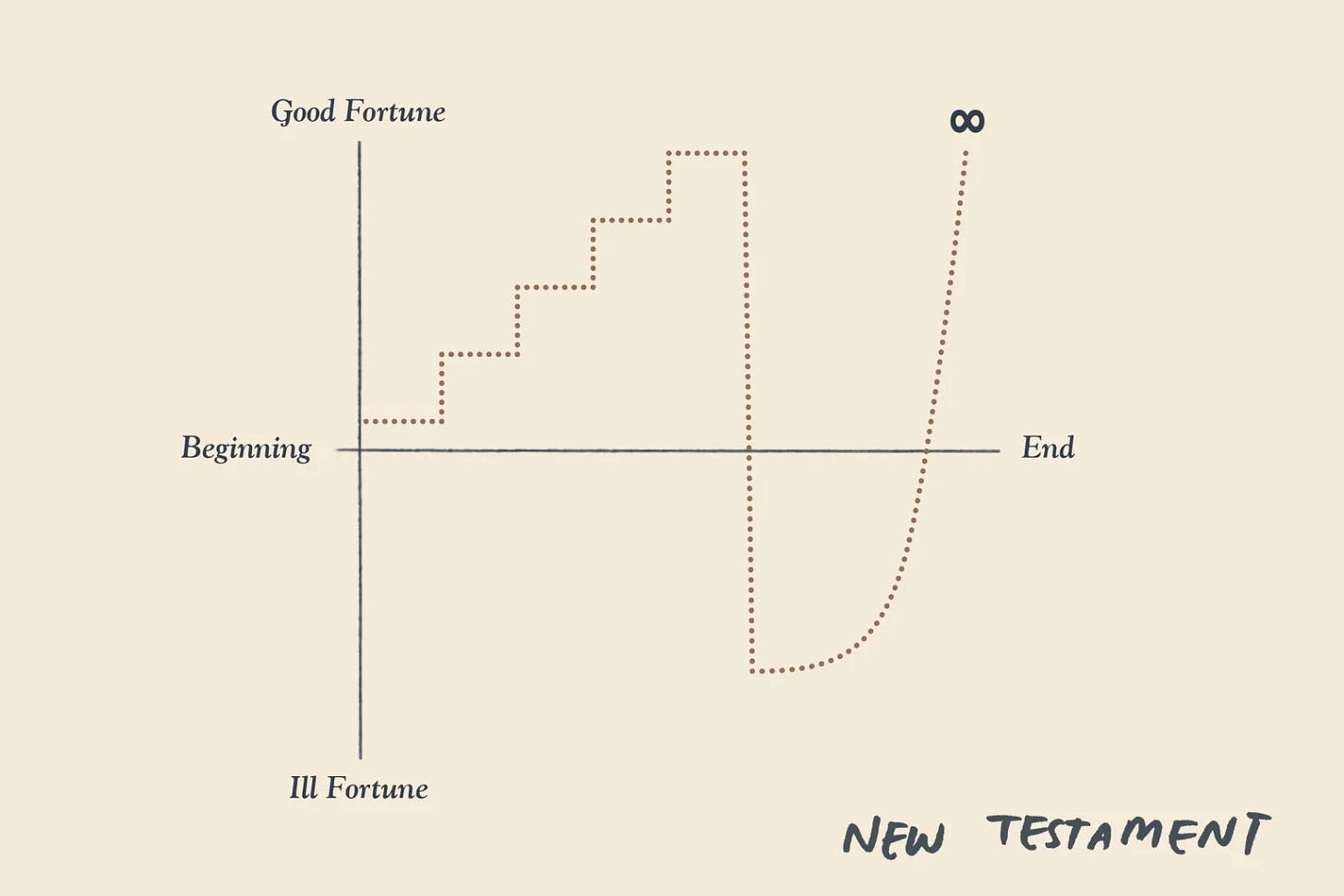

The remaining three or four stories are Creation, Old Testament, New Testament, and Cinderella. In Creation stories, the protagonist gets incremental gifts from the creator—things just keep getting better.

In the Old Testament, humankind gets incremental gifts from a deity, but something goes wrong and they are ousted from favour, suddenly falling from Good to Ill.

In the New Testament, in contrast, there are incremental gifts, then a fall from grace, but they then a sharp recovery.

(Source: The Story)

Vonnegut’s discovery that Cinderella (the eighth story) had a pretty much identical shape to the New Testament was the thing that first piqued his interest in the idea:

His most interesting observation: early Christianity and Cinderella follow the same plot points, the stroke of midnight mirroring our ejection from the Garden of Eden, and Cinderella’s rise to bliss with the prince reflecting our redemption through (Christ).

There’s a handy if busy diagram at a storytelling agency that puts all eight into one graphic.

(Source: Response Agency: designed by Maya Eilam)

There’s similarities with Booker’s seven plots, which for reference are:

Overcoming The Monster, Rags to Riches, The Quest, Voyage and Return, Comedy, Tragedy, and Rebirth.

I’m not going to try and do an analytical comparison, but Booker sees Hamlet, for example, as a tragedy:

The protagonist is a hero with a major character flaw or great mistake which is ultimately their undoing. Their unfortunate end evokes pity at their folly and the fall of a fundamentally good character.

This sounds like a version of Bad to Worse, but starting much higher up—‘Good to Worse’, perhaps. (Booker has Citizen Kane in this group as well.) It starts well, but falls away.

Cinderella, for Booker, is similar to Vonnegut’s version: a ‘Rags to Riches’ plot, in which

The poor protagonist acquires power, wealth, and/or a mate, loses it all and gains it back, growing as a person as a result.

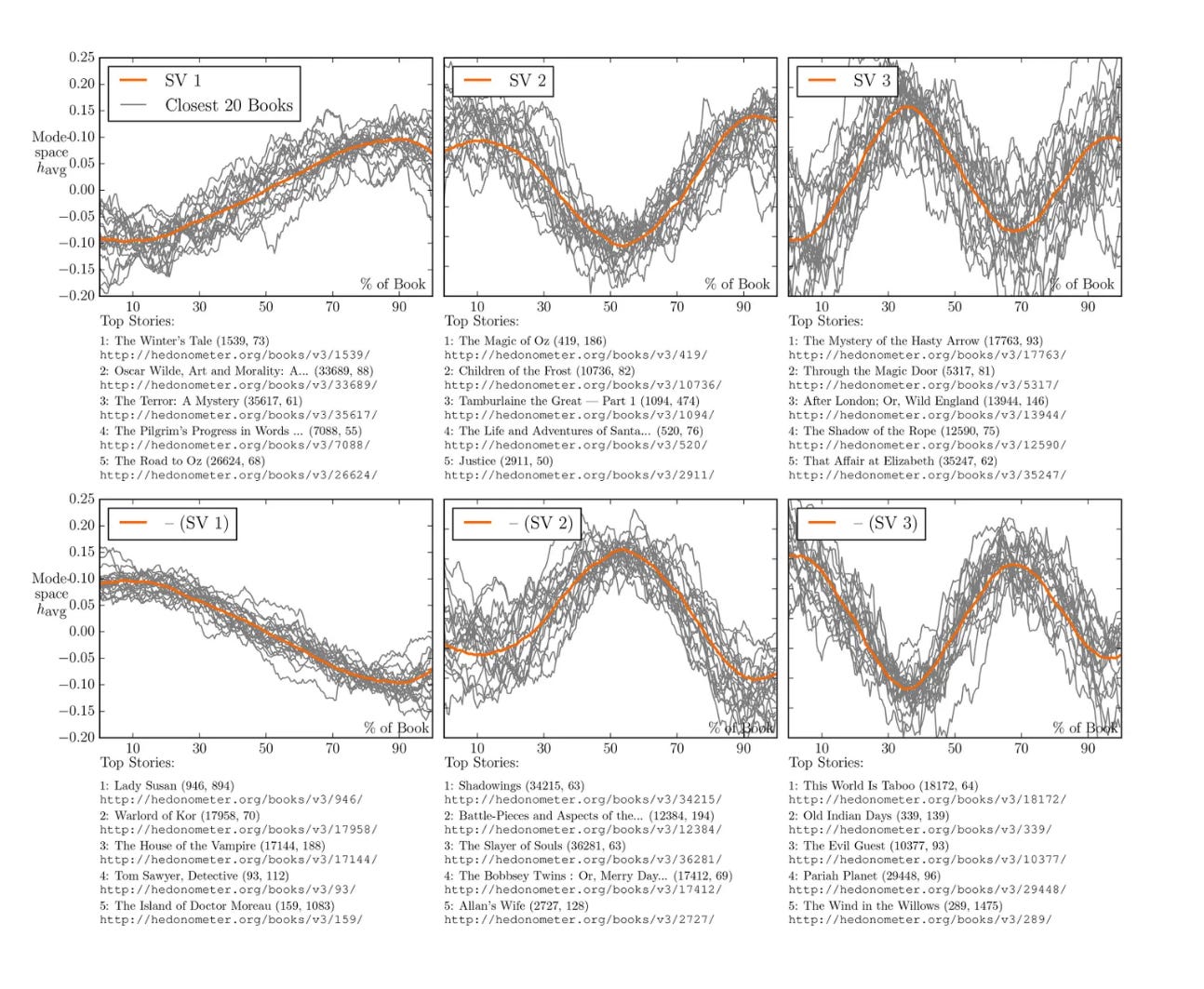

A few years ago, the journal EPJ Data Science published an article in which the researchers described how they had fed 1.327 stories from Project Gutenberg into a computer, analysing a “rolling window” of 10,000 words to understand the trajectory. They found that the large majority of them—85%—corresponded to six basic emotional arcs. The whole article is online if you want to dive into their dense and technical analysis, or you can read a write up in The Cut. But it looks as if Vonnegut’s original idea, which he said started off as “a lark”, had hit on a deeper truth.

(Reagan et al. EPJ Data Science (2016) 5:31. DOI 10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0093-1)

j2t#520

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.