Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: How Davos works

It’s Davos week, which means that the world’s political and business elites are flying in to the Swiss resort by helicopter and private jet to mingle with each other. The worst thing about the annual World Economic Forum event is the temptation to take it seriously.

It produces its own reports—its annual executive survey of risks, for example—and every management consultancy in the world of any size feels to knock some kind of “thought leadership” to show that it has its finger on the pulse of the world’s CEOs.1

Fortunately, that temptation was dispelled this year by The Browser, which decided to mark Davos with daily instalments of a murder mystery that unfolds against the backdrop of the event.

I suspect that the hand of The Browser’s editor Caroline Crampton may be behind this initiative, since she is a well-known fan of whodunnits, and I can’t help but wonder if the author, ‘Emily Adjarian’, may be a pseudonym.

It’s also a members only thing, and I don’t normally feature those here, but the descriptions of how Davos works seem to have been written by someone who knows more about it than is completely good for them.

Of course, this is a work of fiction, and it’s not about the World Economic Forum, but about an organisation called The Circle. The Circle is definitely not run by Klaus Schwab, but by someone called Herr Doktor. And the story is prefaced by the traditional disclaimer:

The people and events described in it spring directly from the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actually existing people and events is entirely coincidental.

The plot: a Ukrainian woman, Olena, who used to work for the Circle, but now is trying to raise investment finance to rebuild Ukraine, is on her way—in Episode 1—to Davos by train. And as she goes, she helps readers understand how Davos works. I’ve never been, but I’ve read plenty of accounts, and this fictional version seemed to have the ring of truth. Here are some extracts.

Olena has one of the coveted White Badges that let her access everywhere. A lot of the attendees aren’t so privileged:

The Circle was not simply one circle, but a set of concentric circles, with The Doc at its centre. The outermost circles were for holders of colour-coded badges who were admitted to programmed talks and discussions only, and sometimes not to all of those. They were the session-fodder. Their job was to listen enraptured to the Finnish Minister of Folklore or the CEO of a Liechtenstein Landesbank while not even noticing that the rest of the room was filled with relative nobodies like themselves.

Anybody who is anybody will be skipping the Finnish Minister of Folklore, and, perhaps, gathering in groups of 12-20 at one of the more exclusive private-by-invitation seminars. But anyone who is really someone will be at one of the breakfasts or dinners that even a White Badge doesn’t get you into:

Attendance to these was reserved for two categories of people, known informally to Circle staff as "predators" and "prey". Prey were the rare celebrities whose names any Circle member would be proud to drop once they were back in London or New York: "I tell you what Barack said to me last week ..."; "I was having breakfast with Angelina ..."; "I don't usually agree with Greta, but ..."

Predators were Circle members who were (a) presentable on such occasions and (b) only too happy to pay the non-trivial supplement for VIP status.

(Davos poster by TravelZonaArt)

It is an environment in which the dynamics of networking become rarified, because everyone is there to network up. But that means that those White Badges, who everyone wants to network with, had better not be embarrassed.

The Circle was a handsomely-upholstered comfort zone for people who had already changed the world, not necessarily for the better, and now wanted to cover their tracks. The Doc's special genius, and the gift which he looked for in his staff, was to create an atmosphere of free-thinking debate while ensuring that everybody understood the limits of that debate and that no White Badge member was ever publicly embarrassed or deeply offended.

The story has a nod towards the Dutch academic Rutger Bregman, who broke this rule a few years ago by suggesting on a panel that the wealthy might like to consider paying some taxes, but this is fiction and the reference is to a woman academic, not a man:

It was not the banality of the complaint which gave offence so much as the complainant's lack of irony. She would not be invited back.

Not that anyone is ever thrown out of a session. Instead a Circle staffer sits down next to them, “praises their ‘bold’ intervention”, and promises that they will continue the conversation afterwards, while having no intention of doing so. Because one of the points of the Circle is that it is a network that is designed to prevent anything socially useful from actually happening:

(M)ost members of the Circle... saw governments, if not as enemies, then at least as predators, as institutions shaped by evolution to ingest money and power and then excrete it in inconvenient places.

Of course, individual government leaders might be perfectly personable.

But anything that any government actually wanted to do, apart from privatisating and policing, was necessarily a bad thing, precisely because a government wanted to do it, and the consequence would therefore be more government. "Lovely idea", as they said at The Circle, "but sadly impossible to implement".

All of this doesn’t make it sound like much of a story. But on the way to Davos, a French journalist who may be funded by the Russian government, gets murdered on the train. And after that...

More about The Browser here.

Previous Davos posts on Just Two Things include:

January 2023: The World Economic Forum pussyfoots around the crisis.

January 2021: Virtual Davos

2: The rise of grift

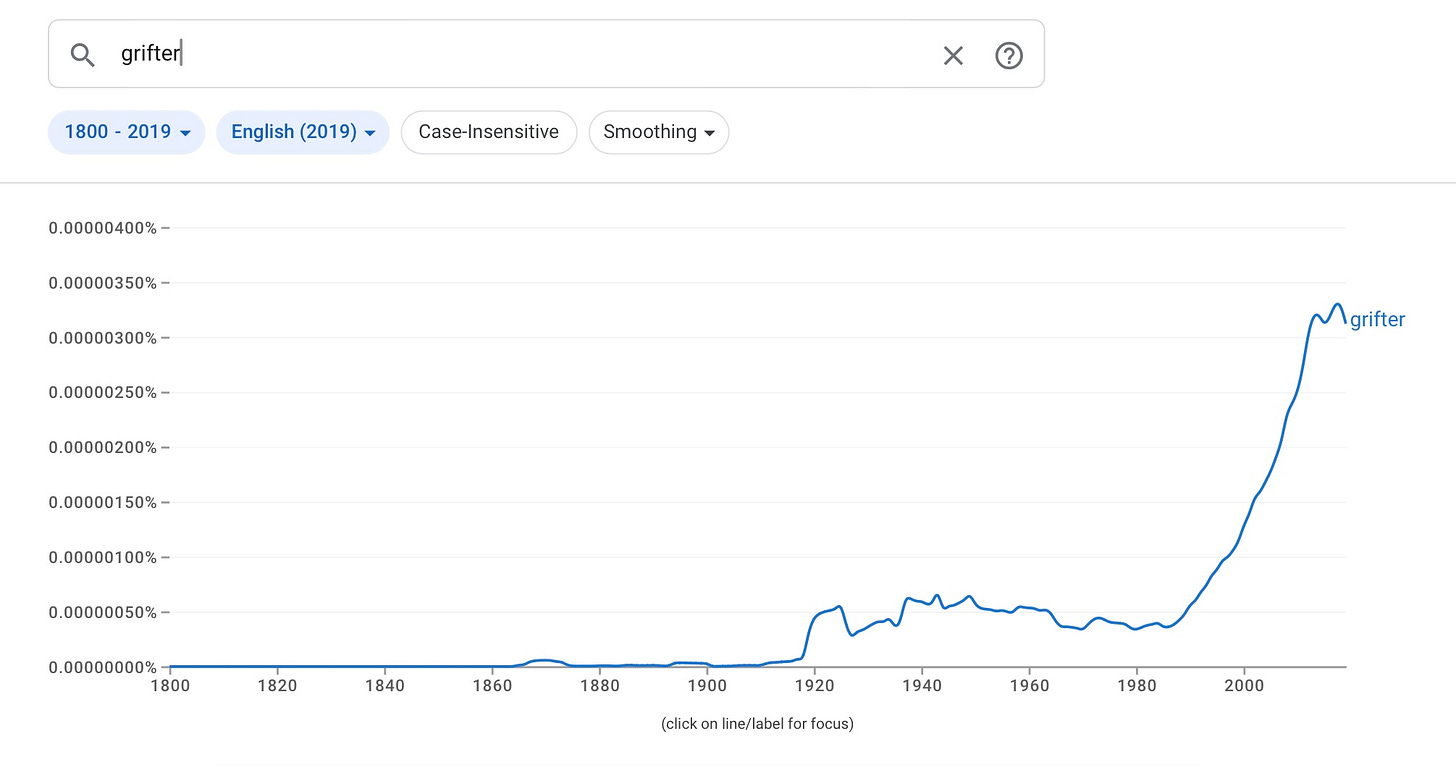

What’s not to like about an article on the rise of grift that starts by way of evidence with an N-Gram of how frequently the word ‘grifter’ has appeared in books over the past 200 years. It’s in the free tier of Byrne Hobart’s The Diff newsletter.

Here’s that chart:

(N-gram: ‘Grifter’, 1800-2019. Source: Byrne Hobart)

But we should probably start with a definition:

The heart of a grift is that it's a promise that could be true: the fitness influencer who says you'll look like a model in four weeks is obviously lying, but the one who offers exercise guides and meal plans that put you on pace for steady weight loss, and who has the before-and-after pictures to prove it? .... (T)he heart of a grift is that you get something that, in a technical sense, is what you paid for, but that is also not worth what you paid for it.

Politics has its share of grifters, and then, of course, there’s finance. He skips past ponzi schemes, which are not so much grifts as scams, to the main two types of finance grift:

(T)he broad categories of finance grift are:

A fancy-sounding high-fee wrapper on something that is trivial to implement manually, and

A strategy that looks good in backtests because it has some kind of nonlinear blow-up risk.

As he says, there’s a lot of both of these around: “one of the biggest historical finance grifts was running a strategy that implicitly replicated the S&P 500, but charged much higher fees than an index fund.” Examples of the second type are pitching a product that has an acceptable track record while omitting to mention the significant risks.

And he suggests that what’s going on here is form of business pathology:

One way to think of it is that it's a particularly pathological example of a company with high churn. Of course, churn rates vary by industry; people stick with checking accounts for a long time—far longer than they do for app-based dating sites. But within the same industry, some companies optimize for keeping customers forever, while others focus on acquiring them quickly, running through them profitably, and repeating that cycle.

So one way I read this is through Geoff Mulgan’s model of capitalism as being about “the locust and the bee”. What he meant by that was capitalism has always included both extractive business models and productive business models, but at different times it leans towards one end of the spectrum or the other.

The deregulation of the financial sector in the 1980s meant that lots of forms of extraction became a lot easier, not least because regulators were less interested, the norms of business leaders slipped, a lot more of capitalism was about moving money around rather than doing something useful with it. So it’s maybe not a surprise to see the ngram shoot up at that point.

Hobart speculates—in a slightly confusing way, to be honest—that the rise of grift and grifters is fuelled by elite overproduction of extroverts, but then suggests that there are now lots more ways that people who are not sociable to get rich:

it's hard to deny that there are many, many more ways for someone who doesn't like social interaction much to get rich. If ads and sales are on the same continuum, then the world's best salespeople are engineers, data scientists, and product managers.

The decline in human touchpoints also, he suggests, might be a source of grift.

The pre-Internet white collar economy was basically a universal job guarantee for personable people. That's increasingly going away, to be replaced with a more neoliberal attention economy with a more extreme distribution of outcomes. And one result of that is that it's possible to craft an online persona as the top of funnel for some product.

One of the examples he gives here is the travel agent. Once upon a time, the travel agent was a person who listened to the kind of holiday you were trying to have and tried to help. Now they just need to have some decent pictures and some enthusiastic recommendations.

Because I suspect that the biggest reason that we’re more interested in the idea of grifters is that the internet has facilitated endless business models based on grift. Every time you book a flight on a budget airline you wade through pages that are designed to confuse you for long enough that you make an additional unnecessary purchase that inflates the airline’s fee and isn’t worth what you pay for it.

Or every time, pretty much, you go to the cinema or a concert, you pay a booking fee that it several orders of magnitude higher than the cost of processing the transaction—and where the poor venue is also locked in because it needs access to a platform.

You need regulation to tackle this kind of grift, and of course, this one of those areas where the US Federal Trade Commission is taking a lead in getting rid of “junk fees”:

The FTC is currently soliciting public comments on this proposed rule, designed to regulate what the FTC sees as pervasive unfair and deceptive practices associated with fees that consumers pay for goods and services.

Comments on that closed last week. There’s already been some performative support. A few months ago,

several major corporations, including some of the largest ticket sellers and resellers, joined President Biden earlier this year to express their commitment to "all-in pricing," which allows consumers to see the full price for goods or services upfront, including fees.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that those corporation leaders took advantage of the photo-op and the reputational wash it offers—and who wants to seem to be in favour of “hidden fees?—while their trade associations and lawyers are doing whatever they need to do to maintain their margins.

UPDATE: Post Office

Trying to keep up with the coverage of the Post Office Horizon scandal is like having a second career, but on lawyers, the legal bloggers Cyclefree—who I quoted in my pieces—and David Allen Green have both had good pieces on the reckoning that the Horizon prosecutions provide for the legal profession.

David Allen Green focuses on those aspects of the legal systemthat made the Post Office prosecutions possible. These are: first, the legal presumption that “computer records must be presumed to be accurate unless shown to be otherwise”. He says this presumption, which came into law only in 1999, partly at the urging of the Post Office, needs to be reversed. Second, rules of disclosure, and specifically, the failure of the Post Office to disclose relevant evidence. And third, the use of private prosecutions:

because these were private prosecutions, there was no direct involvement by the Crown Prosecution Service and thereby no independent appraisal of the prosecution decision.2

Green also observes that the sub-postmasters had two strokes of luck in winning their legal case. The first was that the court agreed to permit to a “group litigation order”—their civil case against the Post Office. The second was that Sir Peter Fraser was assigned as the judge:

This is not a sweary blog, and so forgive the following characterisation. Mr Justice Fraser was not going to take any of the Post Office’s shit.

In a sequence of judgments , Fraser skilfully and painstakingly dismantled the Post Office’s legal and technical case.

Why was this a stroke of luck? Because:

It is difficult to imagine many, if any, other High Court judges with the technical understanding and confidence to do this – and it is scarily easy to imagine many High Court judges instead nodding-along with Post Office counsel.

Cyclefree addresses the concerns that we might end up with Parliament passing a law to exonerate the hundreds of sub-postmasters who still have appeals to be heard, with the associated concerns that the legislature is intervening in the judiciary. She thinks the legal profession only has itself to blame:

A touch of humility from the legal fraternity is needed. More than a touch, in fact. This miscarriage is in large part due to multiple failings over years by lawyers and the legal process, starting with the Law Commission (which recommended the computer law change – explained here and here), via investigators, in-house prosecutors, members of the external Bar, defence lawyers, judges, those supervising or reviewing or even noticing the activities of those bodies with statutory prosecution powers. ...

The legal system does not come out of this story well, however much praise is now due to those lawyers who have worked tirelessly to expose the scandal and help its victims. It is, frankly, a bit much for it to ignore all this in the rush to preserve constitutional proprieties. Doing right is what is needed now, followed by extensive reflection on its own part in this abysmal affair.

j2t#533

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

For example, PWC. Its annual survey of CEOs reveals that 45% of CEOs think that their company will not be viable in ten years if it stays on the same path. Not viable? That sounds like it ought to be quite a high bar in terms of their level of concern, you’d have thought. But apparently not. “Survival-conscious CEOs among the 45% who are less confident of their company’s viability are slightly more likely than other CEOs to have taken action aimed at reinventing their business models.” Slightly. That sounds like leadership. On this aspect of their survey, the PWC report is silent.

The Crown Prosecution Service was actually involved in a small number of cases.