16 January 2023. Collapse | Data

The World Economic Forum pussyfoots around the crisis // Fighting Big Tech over data rights

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The World Economic Forum pussyfoots around the crisis

It’s Davos-time, and the elites and their courtiers and hangers-on are descending on the Swiss resort at the invitation of the World Economic Forum to wring their hands about things they could do something about if they really wanted to.

I’m not a fan, in other words, but there are a few things that are worth noting from the annual jamboree, notably the WEF “‘global risks report”. It’s interesting because it polls the same elites etc mentioned above, so it tracks the way they are thinking about the world.

Here’s their list of the top things they are worrying about on a two-year and ten-year timeframe.

(Global Risks Perception Survey, 7 September-5 October 2022)

This focus on climate change isn’t new—climate change risks have been at the top of the Davos list for a while now—but their dilution in the two-year time frame might explain why the Davos crowd has been fairly ineffective so far in addressing climate change with the urgency it needs, given the way that the lead times work.

In case people think I’m being unfair here, this is the short-run risks map in the report, which includes precisely one thing related to climate change.

(‘Currently manifesting risks’. World Economic Forum, 2023)

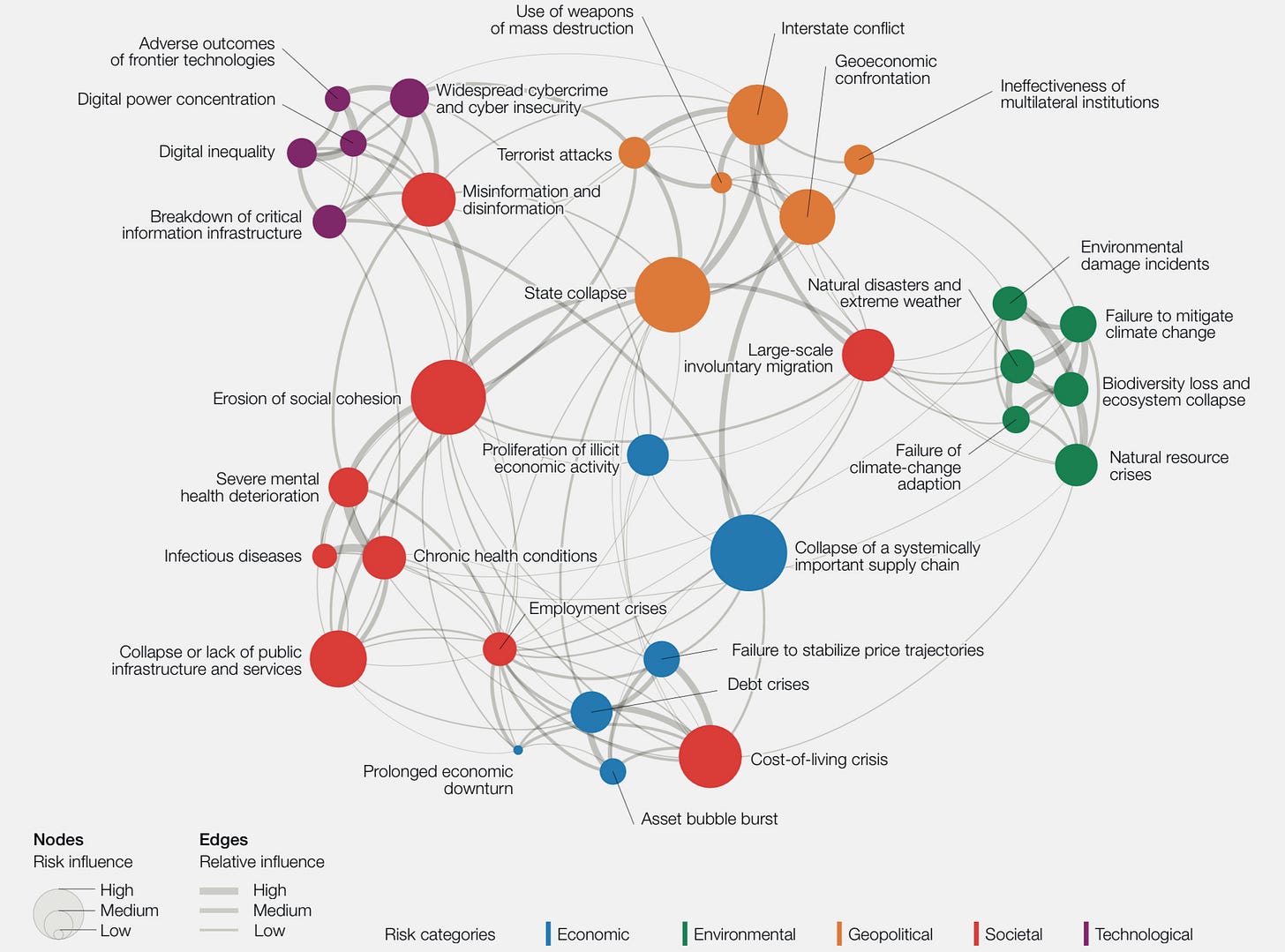

Another reason for the lack of attention on climate and biodiversity risks might be seen in their systemic risks map.

(Global risks landscape: an interconnections map. World Economic Forum, 2023)

There’s a little cluster of rather powerful self-reinforcing climate change effects huddled together at the edge of the map, with surprisingly weak connections to the rest of the risks and issues floating around in the minds of the respondents.

None of the climate issues, judging by the scale at the bottom left, is regarded as that influential. Not compared, say, to state collapse, or supply chain collapse, or the erosion of social cohesion.

But if any of those under-regarded climate change issues start to move, they will amplify all of the others in the climate change cluster, and the knock-on effects of that will be everywhere, and pretty much all at once.

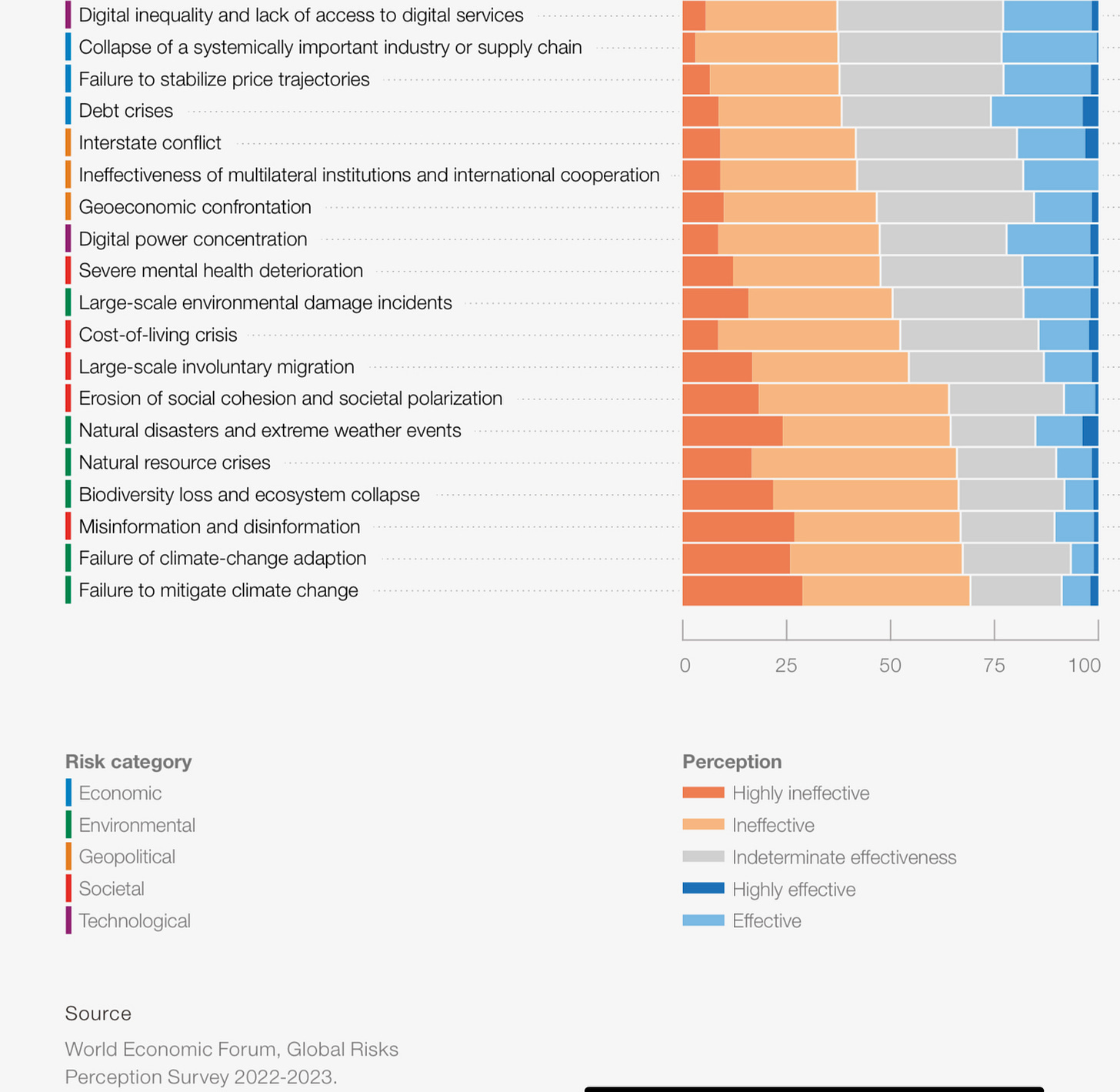

There’s another chart in the same report, immediately following it that seems to make my point here, which is under-commented on. I’ve cropped out some of the detail to focus on what I think is the critical issue here:

(Perceptions around preparedness and governance. World Economic Forum 2023)

Without wanting to lay this on with a trowel, the more orange these is, the less prepared the respondents think we are for the issue. (Blue indicates some level of preparedness.) And guess what? Pretty much all of these climate change issues in that grim green cluster are at the bottom end of the chart: they are the things that the World Economic Forum respondents think we are least prepared for.

I’m perhaps being a little unfair here. When you eventually get into the relevant part of the report (on page 31), the editorial tone is quite concerned:

Over the next 10 years, the interplay between biodiversity loss, pollution, natural resource consumption, climate change and socioeconomic drivers will make for a dangerous mix. Given that over half of the world's economic output is estimated to be moderately to highly dependent on nature, the collapse of ecosystems will have far-reaching economic and societal consequences.

And some of those consequences?

These include increased occurrence of zoonotic diseases, a fall in crop yields and nutritional value, growing water stress exacerbating potentially violent conflict, loss of livelihoods dependent on food systems and nature-based services like pollination, and ever more dramatic floods, sea-level rises and erosion from the degradation of natural flood protection systems like water meadows and coastal mangroves.

Put it like that, and it doesn’t sound like a 10-year problem.

And maybe I’m labouring the point, but I’m pretty sure that we have a decade or less to fix climate change and the biodiversity crisis, and that means thinking of them as urgent issues right now. (I’m not alone in this: the expert reports for both COP27 on climate and COP15 on biodiversity said much the same thing.)

We know that WEF doesn’t like having difficult conversations about things that might dent the corporate worldview. And one of the other things we know about businesses and business leaders is that they are are over-interested in the short-term and the tactical at the expense of the long-term and the strategic.

It’s easy in that kind of boardroom culture to believe that the short-term is somehow more relevant than the long-term. I’ve written these kinds of reports in the past, and I suspect that when they were designing it, someone in one of the meetings said something along the lines that ‘this will have more impact if we look at the two year issues first’.

Somewhere a bit later on, there’s a bit of a discussion of the idea of the ‘polycrisis’, albeit with some fantastically sketchy scenarios. What I deduce from this is that WEF knows what the problems are here, but they can’t quite bring themselves to say it in a way that anyone might notice. So I’m just going to pull out a quote from the passage above and leave it here in bold, by way of a reminder:

Given that over half of the world's economic output is estimated to be moderately to highly dependent on nature, the collapse of ecosystems will have far-reaching economic and societal consequences.

2: Fighting Big Tech over data rights

Last week I wrote about the Irish legal decision against Meta that might restrict its ability to deliver targeted advertising. On The Markdown Julia Angwin interviewed a British tech activist, Tanya O’Carroll, who’s sceptical that Ireland will ever really enforce action against the big tech companies.

The way that (GDPR) works is that the regulator is in the country where the business is headquartered. Ireland is this tiny country, but it is the regulator for some of the biggest companies on Earth because their European headquarters are there... You’ve got a situation where the entire Irish economy depends on foreign direct investment, with a large proportion coming from the tech industry. There is just never going to be political will to properly enforce GDPR in Ireland.

O’Carroll is taking a different approach, testing her rights under GDPR in the British courts:

Facebook has consistently argued that it does not need to gather people’s consent for tracking and targeted advertising—despite what GDPR says. It essentially argues, “We don’t need your consent because you signed a contract, and the contract you signed means we are actually beholden to you—we’re contractually obliged to provide you with a personalized advertising experience.”

I had to read that sentence twice, since it obviously comes out of looking glass world of Big Tech legalese. What O’Carroll’s case does is to move the argument away from contract law into the area of rights. And also from data regulation and data regulators into the courts:

What I’m doing with my case is basically taking the ball into a different playing field. I am drawing on a different right within GDPR, Article 21.2, which gives us all an absolute right to object to the use of our data for direct marketing. Under this provision, it doesn’t matter what contract I signed—or any other legal basis Facebook can argue—because the right is absolute.

(Artist: Zabou, Chance Street, Shoreditch, London. Via Wikipedia. CC BY 2.0)

One of the arguments that Facebook made to O’Carroll when she contested the way that she was profiled was to say that she could go into her settings and untag herself from the ones she didn’t like. They wouldn’t, however, untag her from everything, because of the frankly odd contractual argument made above—that the company would be in breach of its contract to her if they didn’t provide some targeted or personalised advertising.

I wanted Facebook to delete the most invasive categories altogether, and I wanted to turn off the whole thing. Part of the reason I wanted this is because I had already tried turning off individual categories when I had a child in 2017. I didn’t like being bombarded by all of the new baby stuff, so I untagged “motherhood” as a category. But I found that I was still being bombarded by baby stuff because they had just repopulated it with “parenthood” or “children” or “toddler.”

What Facebook has done is remove some of the most controversial categories from its list, even trumpeting this in a news release. Perhaps that is a sign that is aware that it is under pressure. Like all the tech companies, it responds to pressure with the minimum possible response that enables to deflect its critics. (This is ‘dynamic conservatism’ in action.)

But the pressure will keep on coming. Max Schrems, who filed the cases against Facebook that were upheld last week by the Irish regulator, recently got the European Data Protection Board to overturn an earlier decision by the Irish regulator that upheld Facebook’s “contractual” defence on using personal data:

This is absolutely huge and testament to years of smart campaigning and litigation by Max Schrems. The move by the EDPB is very encouraging and may signal a bigger shift in the way that other European member states are going to start pushing Ireland. However, we’ve still got a long way to go. The first problem is that Ireland is still in the middle. They’ve had their preliminary decision overturned, but Ireland still gets to determine the scope of the changes that will be required. Second, Facebook has appealed. That will kick the can down the road for another few years.

O’Carroll was asked by the Markdown editor, Julia Angwin, who did the interview with her, what the best outcome for her legal case would be:

For me it’s the ability to say no to your data being used to target you with ads and other kinds of “direct marketing,” such as the promotion of groups and pages, without losing access to the service. It’s what Apple did last year, in terms of giving people a simple yes or no option on third-party apps tracking them. When they did that, 96% of U.S. citizens said, “No thanks, I’d rather not be tracked by loads of weird apps that I have no idea what they’re doing with my data.” It seems like a very simple thing, but true control across the board is a step toward a very different internet.

What I take away from all of this is that the big tech companies are going to have to adjust themselves to the idea that their huge margins and easy profits are going to be in decline from now on. Their markets are saturated and their business practices are contested. The presence in the ecosystem of Apple, with its different business model, is a problem. (Apple can position itself as being on the side of its customers, if not always honestly.)

The legal cases will keep on coming, and public attitudes are less sympathetic. The business strategy question is how quickly you choose to adjust. Too quickly, of course, and you leave money on the table. But too slowly, and you risk the kind of reputational issues which can lead to tumbling user numbers and user visits. I suspect, since the ‘money on the table’ argument is always a powerful one inside businesses, that they will go too slowly. It is a higher risk strategy.

j2t#415

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.