17 December 2022. Resources | Greenwashing

The Russia-Ukraine war and the future of resources // How to write good greenwashing

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

Have a good weekend!

1: The Russia-Ukraine war and the future of resources

One of the high spots of my year was working with Chatham House to design and facilitate three workshops on the wider and longer-term impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war on food, energy, and mineral resources.

We created a set of short scenarios from an earlier Chatham House roundtable on the possible ways in which the war itself might evolve, and the first workshop used the Three Horizons method to explore these. The second one, on global finance, was designed as a soft simulation, while the third one was a structured conversation about governance implications across resources, finance and security.

The outcomes from the workshops have since been published by Chatham House in a pair of reports.

One of the themes of the work is that the global system is both more interdependent and more tightly coupled:

There are strong interdependencies between markets, the underlying global economy, geopolitics and national security. Connectivity between these mean that emerging risks in one area quickly disturb the behaviour of the overall system.

The first workshop identified three significant consequences for this global system from the war:

food and energy shocks, and related price shocks; the relationship between the West and China; and changing patterns of land use. These are likely to play out over extended timescales, from the short term to the long term.

We were also interested in how these shocks might affect the transition away from the fossil-fuel economy and towards “a decarbonized and nature-positive global economy”.

One of the big changes was that the global nature of the risks actually increases the importance of the nation state:

With respect to both food and energy, the war seems likely to accelerate an existing trend: globally, we are moving from a market-led model for energy and food to a security-led model. Many countries are increasingly seeing both food and energy as strategic resources, and are also seeing that, in terms of food and energy provision, they can no longer be over-reliant on a small number of global producers and traders who respond to market signals.

This has important implications for the form that globalisation takes. The model that we’ve lived with over the last forty years has been dominated by a set of assumptions about the effectiveness of markets in servicing the needs of countries, especially for food and energy.

The second area was about the nature of geopolitics, refracted inevitably through the relationships between China, America, Europe and non-aligned countries. These are also being shaped by these questions of strategic resources, and of reducing the impact of markets in this.

The consensus was that we were moving towards a more regional world, but that relationships between allies would also be economic as well as political (much talk of “ally-shoring” or friend-shoring”, as the currently fashionable phrase has it, rather than bringing production back home.)

The bipolar world is likely to lead to heightened geopolitical competition for influence, especially among resource-rich countries, which is designed to pull them into supply chains and spheres of interest. Beneficiaries are likely to be traditional resource exporters across Latin America and Africa. This could extend into competition between models of international development.

But in an unstable world, it’s also easy for this to go wrong. It doesn’t take much for a world that is slipping into more regional relationship to slip a little futher and go into a fragmented world with far greater levels of mistrust. In a regionally dominated world, multilateral institutions still have a role in acting as bridges and co-ordinators, but in a fragmented world they lose most of their effectiveness.

In contrast, the fragmented world would be more disorderly, with no state or group of states being able to impose order. Potentially, resource holders may attempt to play off different groups against each other, which also opens up the risk of military skirmishes or conflict by proxy.

One of the insights that came up, which surprised me, was that even if Europe or the United States wanted to create better diplomatic bridges to China, there are few mechanisms through which this can be done. This came out most strongly in the soft simulation.

Land use is also affected by this transition towards a greater concern with strategic security. Land use, in general, is a critical part of the transition to a post-carbon world. The trends here seem more favourable than I had expected before the workshop.

Food production has some scope for flexibility in both the short term and the long term: the mix of food can be varied, and if security matters, more marginal land can be brought into use. Longer term, there is a number of technologies that increase production intensity (hydroponics and so on) but some of these effectively trade land use for energy inputs.

Energy production in the fossil-fuel world is very specifically location based. You find oil and gas where they got laid down. But renewables are much more untethered, and can be much more local, in a way that does enable countries and communities to take responsibility for their own energy needs.

Even mineral resources are starting to move in this direction. Again, historically, we have mined them where they have been found. But gold is already cheaper to produce from mobile phones than it is to dig out of the ground, and design can reduce dependence on rare earth metals (which in any case aren’t that rare). Over time, it is likely that some of these materials will be produced through nano- or molecular engineering, although we’re a long way at the moment from doing this at scale and at a competitive cost.

The reason for doing the workshops was out of concern for global governance and the related institutions, and the second report identifies several issues here:

The critical questions for governance and international institutions are twofold. The first is the extent to which governance and decision-making processes can deal with the greater intensity caused by volatility. The second is about shared narratives, to persuade governments and citizens that there is much to be gained from international cooperation.

One of the observations from the work was that multilateral institutions tend to be siloed, and not systemic in their approach to risk. (Financial actors think about the finance system, and so on). This becomes more problematic in a world of climate change, which creates bigger systemic shocks. One of the policy challenges is to

Generate overarching coordination between international organizations working in different contexts (security, finance and the underlying economy) to provide a holistic response to risk cascades, rather than dealing separately with individual shocks.

But the underlying challenge here is about the value, and the legitimacy of international institutions. The second report concludes:

The bigger question is how to create an international political environment in which the contribution of international governance institutions to better, fairer, and more inclusive global outcomes is not only understood, but welcomed.

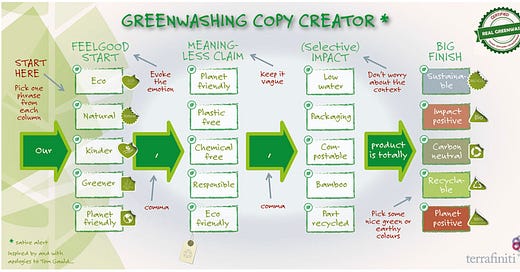

2: How to write even vaguer Greenwashing copy

This time last year I mentioned that the sustainability consultancy Terrafiniti had produced—satirically—plans for a new greenwashing Kitemark.

We’ve listened to the market and people are telling us that while the KitemarkTM provides a beacon of where to head for the ultimate badge of eco bullshit, it can still be tough to do the legwork of creating truly misleading copy.

So, their latest satirical invention is the Greenwashing Copy Creator, which comes with a handy step-by-step visual guide.

(Source: Terrafiniti)

It’s not a long post. But if you do want to make sure that your greenwashing is as wet as it can be they do have four tips:

Hyper selectivity

Get granular. Use laser-like focus to zero in on something small that sounds or looks good – it will make a great headline!...

Truth efficiency

…Don’t bother with knotty problems in your supply chain (like child labour, water use in drought areas, or toxics in manufacturing) just get efficient and talk about what sounds good.

Reality reversal (be bold)

If you’re thinking that this is all a bit small time, and want to get much more ambitious, then it’s time to bring out the big guns. This great tip is to go big or go home with reality reversal...

For example, if you’re one of the biggest plastic polluters in the world you can simply claim that your plastic bottle products help the environment – genius!

Lean on me

Sometimes the old ways are the best ways. Find yourself a nice cosy charity partner.

And if all else fails, and you still haven’t quite got your greenwashing right, they recommend the acronym UTI. Make sure that your copy is unclear, trite, and inaccurate.

Thanks to Dominic Tantram at Terrfiniti for alerting me to this greenwashing breakthrough.

Notes from readers: Commons

I wrote a piece about the idea of the tragedy of the commons earlier this week, and why it was unhelpful. Ian Christie, who teaches on this subject, sent me an interesting summary of how he teaches it:

I’ve been lecturing on this for many years and tell my students that the theory should be called The Tragedy of Open-Access Ungoverned Resource Spaces. The Commons is the remedy — ’the Comedy of the Commons’.

Or more accurately, the Drama of the Commons. The under-reported bit in (Elinor) Ostrom’s theory is just how fragile successful communal governance systems are to external shocks (e.g. an army of colonisers) and to internal corrosion (social tensions, defectors, complacency and failure to adapt etc).

What social media needs, of course, is Ostrom-like governance, which is the last thing liable to be adopted by Elon Musk et al. As it is, they’ve been a nice example, which I have given the students for years, of what an ungoverned or weakly governed open-access resource space looks like.

A commons: a resource space with a constitution that people respect and embody.

Update: Roads

One of the things I mentioned in my recent review of Joe Moran’s book On Roads was the idea of the London ‘motorway box’—an idea that planners cherished for years for an inner London motorway ring road. And just this week, Peter Walker popped up in the Guardian with a long article about the history of the Motorway Box plan—its rise and its fall.

It starts with the history of an odd-looking building in Brixton, south London, called Southwyck House:

Known locally as the Barrier Block, the building looks that way for a reason. It is an almost accidental relic of an alternative history for London, one that would have made the city very different and, as most people would probably agree, significantly less appealing.

This slab of roadside frontage was designed to be not just social housing but also a vast acoustic shield, screening the neighbourhood from the deafening roar of an elevated, eight-lane urban motorway.

(Southwyck House, Coldharbour Lane SW9. Photo by © Robin Sones. CC BY-SA 2.0)

j2t#407

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.