11 December 2022. Commons | Transport

The commons aren’t the tragedy. The problem is exclusive property rights. // Protected bike lanes are good for everyone.

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: The commons aren’t the tragedy. The problem is exclusive property rights.

I was listening to a presentation by someone at the weekend on the challenges of the Anthropocene, and the speaker said that one of the issues was the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’. I’ll come back to this in a moment, but I realised while they were speaking that they were wrong about this particular story. (I’m not going to name them because in most of their work they have a deep systemic understanding of our unfolding crisis.)

The idea of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ was developed by Garrett Hardin, and it has been controversial for a while. Hardin argued, in 1968, that common resources were likely to be depleted, or destroyed, by over-use. Everyone who had access to the commons (for example to graze their animals) had an incentive to use it more than they ought to.

It sounds as if it makes sense. Put like this, it sounds like a misaligned incentive structure. Of course the commons will be exploited, or over-exploited. Hardin thought the solutions were regulation or privatisation.

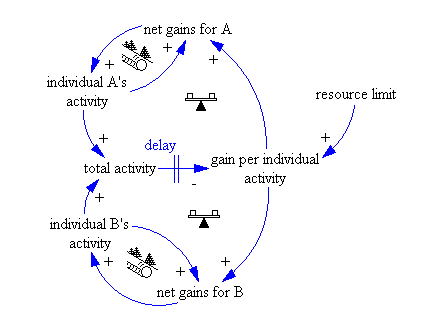

Wikipedia’s long article on the subject says that the causal loop diagram for the Tragedy of the Commons is one of the 10 most common in systems work.

(Causal loop diagram for the tragedy of the commons. Wikipedia.)

Except that there are a couple of problems here. The first is that most of the actual evidence about how human societies use commons doesn’t lead to depletion or exhaustion. Elinor Ostrom won her Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for demonstrating this.

The second is that Hardin’s argument came from a very particular worldview: it treats humans as economic self-maximisers rather than social co-operators. On the first point:

(Ostrom’s) field research in Maine, Indonesia, Nepal and Kenya led to the development of a set of design principles which have supported effective mobilization for local management of common pool resources (CPR) in a variety of areas. She argued that common resources are well managed when those who benefit from them the most are in close proximity to that resource. For her, the tragedy occurred when external groups exerted their power (politically, economically or socially) to gain a personal advantage.

On the second, this critique of Hardin’s framework was made by the anthropologist Arthur McEvoy:

The shortcoming of the tragic myth of the commons is its strangely uni-dimensional picture of human nature. The farmers on Hardin's pasture do not seem to talk to one another. As individuals, they are alienated, rational, utility-maximizing automatons and little else. The sum total of their social life is the grim, Hobbesian struggle of each against all, and all together against the pasture in which they are trapped.

At risk of playing the man and not the ball, it’s also worth noting that Hardin was a social conservative whose views on commons might have been influenced by his political views. To be fair, he recanted about 25 years later, when he said that perhaps his article should have been called ‘the tragedy of the unmanaged commons’. But by then the damage had been done.

As it happens I was involved in a conversation about the commons recently in a discussion group I’m involved in on post-human futures. One of the concepts we talked about was Barbara Heinzen’s distinction between ‘column rights’ and ‘mosaic rights’.

(Barbara Heinzen, ‘A Short Description of Mosaic v Column Rights)

Under column rights,

whoever owns an acre of land owns the air rights and the mineral rights underground as well as everything in between – a ‘column’ of rights. These ‘exclusive’ rights need fences to keep others out. In contrast, a mosaic rights landscape is crisscrossed by footpaths, because these rights are ‘inclusive’, offering everyone some share in the land’s wealth.

To expand on this slightly, it’s possible that different people have different rights to an area of land—and even at different times of the year. Some people might have grazing rights, some people might be able to fish from the stream, others might have the rights to gather firewood. And so on.

An important point here is that the ‘commons’ was not distinct from its users, as Heather Menzies argues:

Historically the commons referred not just to the physical land but to the people who inhabited and used it. The word meant ‘together-as-one’, and bound together by obligation.

Most of our commons were expropriated through enclosure. In the British context, the enclosure movement is usually associated with a rolling programme of acquisition, initially by the Crown, later by large land-owners and in some cases by industrialists, backed by laws passed by the same people. There’s a version of this history that says that the English and later the British state got practice by doing this at scale in its colonies.

Guy Standing’s book Plunder of the Commons unravels some of this history. In a review in resilience.org, David Bollier describes enclosure as ‘pervasive’:

The great contribution of Standing’s book is to show how enclosure is a pervasive phenomenon in contemporary politics—yet barely remarked upon by the political classes... Economic growth and “progress” have always depended upon the coercive seizures of the people’s wealth – something that free-market economics has striven to disguise and ex-nominate (make invisible through words).

The reason this is not a theoretical discussion is because of where we started—in trying to understand the elements of the current crisis. When I’m looking at climate change, for example, one of the big things that’s causing problems right now, and has done for 30 years or more, is the influence of the fossil fuel companies in lobbying politicians and misleading citizens and consumers.

They not behaving like this because a commons in energy has somehow broken down. They’re doing this because they are trying to squeeze out, literally, as much value as they for their shareholders can from the exclusive column rights they have in oil extraction. Leaving the rest of us to pay the price.

2: Protected bike lanes are good for all road users

Maybe this should have been done sooner, but I’ve just noticed a report on a long-term analysis of bike lane safety in seven American cities between 2000 and 2012. (The story comes from 2019, but it was news to me). The researchers looked at 17,000 fatalities and 77,000 serious crashes involving cyclists over the period.

The findings: protected bike lanes increase road safety for everyone (not just the cyclists); coloured lanes on the road surface have no effect either way; and painting bike signs on the road surface actually makes things worse for cyclists.

Cities with protected and separated bike lanes had 44% fewer deaths than the average:

“Protected separated bike facilities was one of our biggest factors associated with lower fatalities and lower injuries for all road users,” study co-author Wesley Marshall, a University of Colorado Denver engineering professor, told Streetsblog. “If you’re going out of your way to make your city safe for a broader range of cyclists … we’re finding that it ends up being a safer city for everyone.”

(If in doubt, concrete planters work well. Protected bike lane in Vancouver. Photo: Paul Krueger/flickr. CC BY 2.0)

“Everyone” here includes drivers and walkers. The researchers had started with a hypothesis that having more cyclists on the streets reduced crashes. There’s a study to this effect, and the rationale is that if there are more cyclists on the streets, motorists are more likely to notice them.

But it turned out that this isn’t the case. What makes a difference is protection—and these reason for this is that protected lanes also influence driver behaviour:

“Bike facilities end up slowing cars down, even when a driver hits another driver, it’s less likely to be a fatality because it’s happening at a slower speed,” Marshall said.

There’s data in the story on the rate of decline in different cities, but it’s sizeable.

The effect of painted lanes: not so much. Or not at all, if fact:

Researchers found that painted bike lanes provided no improvement on road safety. And their review earlier this year of shared roadways — where bike symbols are painted in the middle of a lane — revealed that it was actually safer to have no bike markings at all.

The reason, according to Wesley Marshall:

“It gives people a false sense of security that’s a bike lane. It’s just a sign telling cyclists it might just be there.”

Design still matters. Protected lanes which give vans and cars leeway to stop in the lane (for example to unload) create danger by forcing cyclists out into the roadway.

It’s an American study, and American driving conditions are different. All the same the numbers are striking enough that you’d expect to see something similar if it was replicated in European conditions.

One further detail that caught my eye, which I hadn’t previously been aware of. There’s a ‘gentrification effect’ in cycling safety—the researchers noted “the safety disparities associated with gentrification,” and had to allow for this in their analysis.

These “equity issues”, they say, need further research.

j2t#406

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.