12 June 2024. Germany | GenZ

Unpacking the political success of the AfD // What the world looks like to America’s GenZ [#580]

Welcome to Just Two Things, which I try to publish three days a week. Some links may also appear on my blog from time to time. Links to the main articles are in cross-heads as well as the story. A reminder that if you don’t see Just Two Things in your inbox, it might have been routed to your spam filter. Comments are open.

1: Unpacking the political success of the AfD

It should be Germany’s big week this week, since football’s European Championships start in the country on Friday with a match in which the hosts play Scotland. But of course, that is being overshadowed by the European election results, in which the far-right AfD got 20% of the vote.

The Guardian’s excellent sportswriter Jonathan Liew managed to connect these together, reporting on a documentary on German football by Philipp Awounou, Unity and Justice and Diversity. His article starts with this scene in Thuringia, deep in eastern Germany:

“The team is no longer German,” explains an older gentleman in a baseball cap, calmly loading shopping into the boot of his car. “If you look at how many Germans still play, it’s a joke.”

“How do you define who a German is?” asks the presenter, a documentary-maker named Philipp Awounou.

“For me,” the man replies, “a real German is – and I don’t want to offend you – light-skinned.”

There’s a bit more here—Awounou’s mother is German—but Liew’s summary seems on the mark:

a regular guy, in a regular supermarket car park in Thuringia, perfectly happy to unburden his racism on camera, to the national broadcaster ARD.

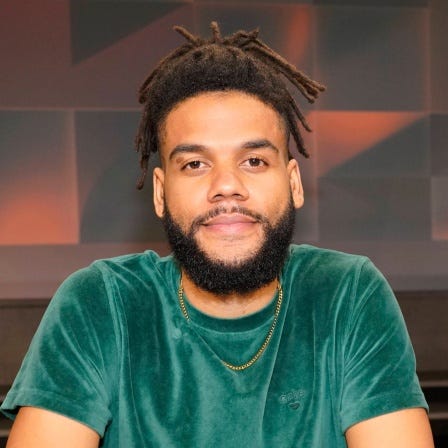

(Philipp Awounou. Photo: ARD)

When the television channel ARD screened the documentary last week, it also ran a poll later criticised for being racist (the critics included the German team manager Julian Nagelsmann and the vice captain, Joshua Kimmich.) And you can see why: this was the question:

“I would prefer it if more white players played in the German national team again.”

In favour, 21%; against, 65%.

It’s easy to assume that racism is resurfacing Germany again, or, probably more exactly, that it never went away and the rise of the AfD has legitimated the open public expression of racism. (I’m not judging here. Exactly the same thing has happened in Britain with the Brexit vote and the endless—and unjustifiable—appearances of the hard right political figure Nigel Farage on BBC Question Time.)

This reminds me of a notion of the 40-year cycle in social and political life (an almost completely unevidenced notion, I should say). Here, it is a bit more than 30 years from the end of the Second World War to the height of the Red Army Fraktion, whose violent existence was a response to the silence then in Germany about Nazism. The music of Kraftwerk, similarly, was a cultural response to this.1

And it is a bit more than 40 years from there to here.

All the same, we should pause here, because one of the narratives about the AfD more or less asserts a connection between being east German and being anti-immigrant, racist, and so on.

But I was reminded of a book review from last year on the Verso blog that suggested that there were deeper and more predictable economic reasons for all of this. Lizzy Kinch reviewed two books: Katja Hoyer’s history of the German Democratic Republic, Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990, and (in German) Dirk Oschmann’s Der Osten: eine westdeutsche Erfindung (which translates as The East: a West German Invention).

It’s too long a review to do complete justice to it here. But the story it tells is clear enough. Unification in 1990 was not so much unification as dispossession:

Reunification meant the rapid alignment of the GDR with the West’s market economy: regardless of their prosperity, the GDR’s 8,500 state-owned businesses were hastily privatised or closed down. Referred to as a “gold rush” (or “the greatest white-collar crime since the second world war”), 80% of these companies had been sold off cheaply to Westerners by 1994 and 14% to foreigners... As the East German writer Ingo Schulz states: “There is no other region in Europe where the population owns so little of the land they live on, where so few can call property and businesses their own as in the East of Germany."

Or again:

Twenty months after reunification, 75% of employees at state-run enterprises in the East had lost their jobs and 4,000 companies had been closed down, while rapid deindustrialisation left up to 50% of 25-45 year-olds unemployed in some regions... These problems were not resolved as the 1990s wore on: by 2005, a fifth of all East Germans were unemployed; permanent poverty (over a five-year period) is six times more common in the East than in the former West; wages are still 22.5% lower.

(The Arcelor Mittal plant in Eisenhüttenstadt employs 900 people. In the GDR it employed 16,000. Photo by Oberlausitzerin64 /wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Put like this, east Germany looks a lot like the cities in Britain and the United States that lost out to de-industrialisation, and which responded by voting for Brexit and for Trump. I wrote about this in 2017, following Lash and Urry’s analysis of ‘migratory capital’ that had lost any sense of place:

The losers from this are Justin Gest’s “post traumatic” cities, “exurbs and urban communities that lost signature industries in the mid- to late-twentieth century and never really recovered.” Behind 21st century populism sits a longer economic history of ’80s deindustrialisation.

Kinch observes that despite the obvious structural analysis that could be made here, the German media tends instead to rely on lazy stereotypes about Ossis. Oschmann’s book documents the way in which east Germans are othered in the media, leading to

the association of the East with “ugliness, stupidity, laziness, racism, chauvinism, right-wing extremism and poverty”.

The othering extends to politics. When the AfD became the leading party in Saxony and Thuringia in the 2021 elections, the government’s special commissioner for East Germany didn’t point to socio-economic issues but the political history of the East:

“We are dealing with people who are partially socialised by dictatorship in such a way that they have not reached democracy, even after 30 years.”

As Oschmann says in his book, this merely reinforces the sense that the AfD is the only party that listens:

by constantly dismissing Easterners, these voices increase the likelihood of more voters turning to populist parties that play upon a sense of exclusion, disaffection and victimhood.

Jonathan Liew records a moment in the documentary when an AfD spokesman plays down racism:

“Racism exists, and it’s a problem, but it’s not our most important problem,” an AfD politician argues in the ARD documentary. “Nothing very important.”

At least, looking at the wider context and the bigger structural story, maybe it’s only a symptom. Because it’s also a reminder that if centre and centre-left politicians want to do anything about the far right, they need to stop imitating their policies (you’re never going to outflank a far right party on immigration). Instead, they need to be talking about a better social and economic settlement for everyone.

2: What the world looks like to GenZ

The American academic Timothy Burke has a piece on his Eight by Seven blog where he tries to look at the world through the lens of his GenZ students. Obviously they are in the spotlight at the moment because they insist on occupying campuses in protests against America’s continuing support for the Israeli assault on Gaza, but that’s not his main interest here.

The piece has an American perspective but many of the points he makes here apply elsewhere. His starting point is that their disquiet over American policy on Israel is an indicator of something larger:

a much vaster, more diffuse sort of generational disaffection with formal politics that the older leadership of the Democratic Party and their older generational supporters are fundamentally incapable of speaking to or grasping.

The election message that comes out of the Biden campaign is that the economy is doing OK, even picking up, the fundamentals are good, and so on. Burke thinks there are good reasons for young people to be a bit doubtful of this: “It is not the America they see”.

The article runs through a list of reasons why this might be the case, which I’m going to summarise quickly here, because it’s getting late.

1. Work. The picture of employment that is touted as being positive generally isn’t that positive for them.

Peter Coy in the New York Times recently verified that recent graduates aren’t wrong when they report that job-hunting is going very badly for many of them. Moreover, many of the applicants are now dealing with the use of poorly-functioning AI screens by human resources departments that are sifting out many qualified or excellent candidates.

Even when in work, they find their hours and wage rates gamed by employees to prevent them from qualifying for benefits or earning more.

Prospects. Lines of work that once offered some economic security or stability are disappearing. And many employers have no interest in loyalty or even security:

virtually no employing organization, profit or non-profit, seems to have any long-term stability or seems to have any loyalty to the employees it is bringing on board. The autonomy of the professions is vanishing even when there’s an ongoing need for their expertise.

Instead, they see financialised businesses that “who are plundering the economy and society in the short-term and have no interest at all in building value over time.”

(‘Fighting for rights in the gig economy.’ Photo: David Alberani/flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

Housing is tight and expensive.

All the places they want to be, that their ambitions or aspirations require them to be, are more expensive than they can afford even if they find roommates and are willing to live in a space no bigger than the dorm rooms they’ve just left.

And public goods and public spaces that might ameliorate this are shrinking.

Health care. This is a particular American issue, of course, since it has an expensive health care system that can bankrupt you if you don’t have the right insurance (and see /1/, above). They

have no reason to believe that the world’s most expensive health care system with some of the world’s worst outcomes will get any better in the years to come. At least some of the youngest generation of adults are also seeing the other side of “deaths of despair”: parents and grandparents whose life expectancy is going down.

Climate. The young are facing the actual existential crisis of climate change (as opposed to the made up existential crisis of AI). There’s pretty good evidence of mental health effects from this.

The youngest generation of adults have reasonable expectations of having to cope with massive disruptions at a global scale from climate change in their middle age. They are facing a world where liberalism seems deeply in peril and the likelihood of major global or regional wars is increasing.

It’s worse than that, actually. Burke runs through a list that includes failing infrastructure, an oligarchic billionaire class that is an ugly symptom of wealth inequality, the notions of “disruption” that don’t seem to be in their interests, and the slowing of the rate of scientific innovation. (See /2/ above.)

Leaders When they look at the aging class in charge, they see a generation of Boomers who benefited from public subsidies, and when they look at their managers they see people who benefited from the last period of economic stability, before the financial crisis, patronising them for “ridiculous expectations and woke pretentions”.

They see a substantial group of political leaders and civic actors who are incompetent clowns and revolting demagogues who evade responsibility and consequence at every turn and realize that all the things they’ve been told about honesty, probity, and talent are more and more false every day.

(Smile and selfie. Public domain)

7. The Democratic Party plays the ‘American fascism’ card, hoping and expecting that they’ll turn out to vote again (“like they did in 2018, 2020, and 2022”), while rigging its internal processes, and being unresponsive to any of their concerns.

Biden has governed well in the sense of basic competency and management in an everyday sense, but he is not speaking at all to this vast terrain of fear, alienation and melancholy, to the futures that young Americans are facing. There is no vision on offer, just a random dog’s breakfast of technocratic responses and balancing acts.

In the place of “an infrastructure of hope”, there is “a drip-drip-drip of limited and highly controlled appearances.”

Burke thinks that most of this has been true since 2016, and that the trends had been shaping up since 2010. Until 2020 it might have been possible to hope that it was a blip. But the exit from the pandemic made things worse, but no-one in public life is willing to acknowledge this or speak to it.

If the moment comes where their dismay and disaffection bursts into sustained anger, it is going to make Gaza encampments of this spring seem like nothing at all—not the least because that anger will not just be on elite campuses or in blue cities.

But avoiding this requires politicians who are willing to take it on—who are willing to

acknowledge the shortcomings of political and civic leadership in the 21st Century. To begin to concretely sketch out a vision of a better future.

There are some themes here. One is financialised businesses whom it is impossible to trust yet no one is willing to regulate. Another is the lack of any long-termism in public or business life, even though the serious problems we face are long term problems. Another is the way in which the housing crisis (another symptom, everywhere, of the crisis of extreme wealth) creates persona, social, economic and political problems, and yet, again, politicians are unwilling to do even minimal things to address it. In fact, I’m not sure that our politicians—in the US and here—have a clue about how serious all of this is.

I’ve long had a view that at some point we’ll see a generational jump in political leadership, although in the United States’ gerontocracy seems to be testing that theory to destruction. But the point is this: without some kind of vision, and without some honesty, that generational jump is more likely to come from the right than the left.

(Hat tip to John Naughton’s Memex 1.1 blog for the link.)

j2t#580

If you are enjoying Just Two Things, please do send it on to a friend or colleague.

See Uwe Schutte’s book Kraftwerk: Future Music From Germany (Penguin, 2020), for more on this.